Royal Pharmaceutical Society

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) celebrates its 175th anniversary on 15 April 2016. Historian SWF Holloway describes the Society as having a “special place in the history of professions in Britain”, taking on a wide range of functions. “It was, at one and the same time, a qualifying authority, an educational institution, a scientific society, an occupational and trade association, and a benevolent society,” says Holloway in his book ‘Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain 1841–1991: a political & social history’[1]

.

The world of pharmacy was very different 175 years ago. In 1841, almost anyone could earn the title of “chemist and druggist” through a period of apprenticeship in a pharmacy with no examinations to pass. It was this lack of regulation and the need for a clearer distinction between apothecaries (in modern terms, general practitioners) and dealers in drugs (chemists and druggists) that eventually led to the establishment of the Pharmaceutical Society.

Formation of the Pharmaceutical Society

In the early 1800s, there were huge divisions within the medical profession. Groups of chemists and druggists had already been involved in a number of campaigns to fight for the interests of their profession: from successfully arguing for an exemption from the Apothecaries Act of 1815 (which introduced compulsory apprenticeship and formal qualifications for apothecaries) to creating the short-lived General Association of Chemists and Druggists to promote protection against the 1812 Medicine Stamp Duty Act, which required a duty stamp to be fixed to the packaging of non-standard medicines.

On 15 February 1841, a small, anxious subgroup of chemists and druggists convened in London to discuss the implications of a proposed medical reform bill that would reorganise the whole medical profession. If the bill became law, their businesses would be ruined. They would be unable to prescribe, give medical advice or perform minor surgery. Jacob Bell, son of a Quaker chemist, emerged as a spokesperson for those concerned — he argued that the proposed act would seriously damage the trade. “It ought to be left to the public to decide whether they would go to the physicians or apothecary, or be content with the aid of the chemist and druggist,” he said.

Courtesy of the Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

Jacob Bell, founder of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain in 1841

The group decided at the meeting to petition parliament against the bill, which was eventually withdrawn. It was a considerable victory for the chemists and druggists, but they had many more battles to fight and the idea of uniting officially as a society frequently came up in discussion.

On 15 April 1841, a public meeting of “the members of the trade” was held at the Crown and Anchor Tavern on the Strand, London — the same tavern where the chemists and druggists had met two months previously to discuss the medical reform bill. The principal item on the agenda was proposed by William Allen, Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS), and seconded by John Bell (Jacob Bell’s father). The proposal, which was carried, read: “That for the purpose of protecting the permanent interests, and increasing the respectability of chemists and druggists, an association be now formed under the title of ‘The Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain’.”

First issue of The Pharmaceutical Journal

On 1 June 1841, William Allen was elected the Society’s first president and 40 people were appointed to its council. It served until elections in May 1842, when a council of 21 members was formed. Keen to promote the Society and armed with wealth and literary talent, Bell distributed more than 2,000 copies of his pamphlet Observations addressed to the Chemists and Druggists of Great Britain on the Pharmaceutical Society to various parts of the country.

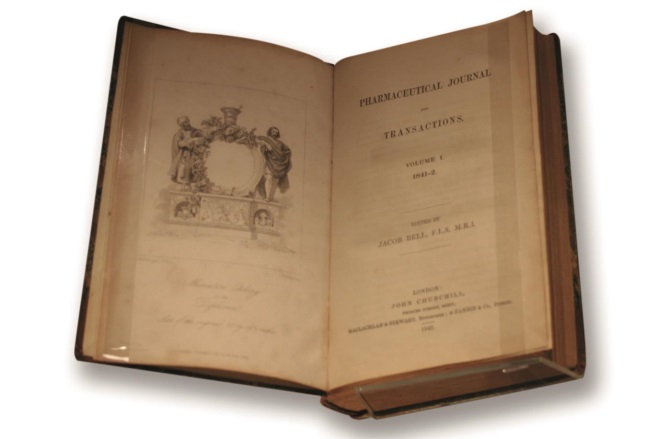

Courtesy of the Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

First issue of Pharmaceutical Transactions later to become The Pharmaceutical Journal

In August 1841, Bell published Pharmaceutical Transactions — a scientific journal explaining the nature and objectives of the newly formed Society, featuring a series of his own accounts of pharmacy in Britain and abroad. However, in September, several members argued that the activities of the Society should be separate from other published material, and so the The Pharmaceutical Journal was born. Named to clearly separate it from the Society’s transactions, The Pharmaceutical Journal was considered one of the few “class” periodicals of the time, joining The Lancet, which was first published in 1823.

Bell was editor of The Pharmaceutical Journal from its inception in 1841 until his death in 1859, and Holloway said he controlled the Pharmaceutical Society for the first 18 years of its existence. However, apart from being editor of the journal and a member of the Society’s council, he held no other office until he was elected president in 1856.

Initially, the Society held its monthly scientific meetings at Bell’s house. But in December 1841, the council decided to hire more suitable headquarters at 17 Bloomsbury Square. The council met there for the first time on 6 January 1842 and the Society listed its founding members in the journal on 1 January 1842. The attention of the council then immediately turned to establishing a school of pharmacy, library and museum on site.

Building a reputation

The Arsenic Act of 1851 highlighted the need for a legal definition of a chemist and druggist because without one the Act could not restrict the supply of arsenic. This resulted in the 1852 Pharmacy Act, which established a register of pharmaceutical chemists for those who had passed the Society’s exams (although unexamined and unregistered people could still practise as pharmacists). This was a victory for the Society, aided by Bell’s position as an MP for St Albans. Efforts to establish a legal status for chemists and druggists became an uphill struggle in July 1852, when Bell lost his parliamentary seat after two years in post.

Despite this, the Pharmaceutical Society continued to build its reputation. In 1854, the Royal College of Physicians approached the Society’s council to ask for its assistance in the compilation of a British Pharmacopeia. The council appointed a Pharmacopoeia committee, which set about collecting details of drugs in use by circulating a questionnaire to the Society’s members. This information was then used to advise the Royal College of Physicians on what should be included.

Bell died, aged just 49 years, in 1859 — the year in which Chemist and Druggist magazine was launched. However, his work was rewarded posthumously when in 1868 a further Pharmacy Act was passed stating that all pharmacists had to be examined and registered by the Pharmaceutical Society in order to sell, dispense and compound poisons and dangerous drugs. There were two examinations that could be taken: a minor exam to become a chemist or druggist; or a major exam to become a pharmaceutical chemist. By 1872, all pharmaceutical chemists were required to become members of the Society and, in 1898, by way of the Pharmacy Amendments Act chemists and druggists could also become members as well as registrants.

Women in the Society

Today, women comprise the majority of the pharmacy workforce. But in the 1800s, attitudes towards women pharmacists were different: in its early years membership to the Society was exclusively for men.

Fanny Deacon (née Potter) was the first woman to qualify for registration with the Pharmaceutical Society following the 1868 Pharmacy Act. She appeared on the Society’s register as a chemist and druggist in 1870, having qualified on 5 February 1869 after taking the minor exam. In 1879, after a considerable battle, Isabella Clarke and Rose Minshull were elected the first female members of the Society. This was an important step in increasing the status of women pharmacists, but there was still much to be done to enable women to fulfil their potential in the profession.

The first meeting of the Association of Women Pharmacists in 1905 was described by Chemist and Druggist as “both historical and novel”. Participants discussed the challenges of finding employment and established a locum register and register of all qualified women. To join the Association of Women Pharmacists, members of the Society had to pay five shillings while non-members had to pay ten shillings.

Margaret Buchanan, who served as the association’s president and was also the first female member of the Pharmaceutical Society’s council, said that by 1912 the association included “practically every woman practising pharmacy”. Some 35 years later, in 1947, the Pharmaceutical Society elected its first female president, Jean Kennedy Irvine.

Courtesy of the Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

Jean Kennedy Irvine, the first female president of the Pharmaceutical Society

The past 100 years

Attitudes towards healthcare have changed dramatically over the past 100 years. In 1911, the National Health Insurance Act formed part of wider social welfare reforms introduced by the Liberal government between 1905 and 1915. It was one of the most expensive and controversial of the reforms. Insured people, comprising working people and not their dependents, were able to receive free prescription medicines, so the impact of the Act on pharmacists was huge.

The Poisons and Pharmacy Act of 1908 was also important as it enabled the Society to make by-laws to regulate courses of study and qualifying exams. This eventually led to the development of a compulsory syllabus focusing on the needs of pharmacists dispensing under the new National Health Insurance scheme.

During this time, Britain also experienced two world wars. Despite a link between the Society and the War Office, the question of whether pharmacists should be employed in the army made little progress. Towards the end of the Second World War, the society set up a War Aid Fund to help pharmacists and others who needed financial assistance as a result of the war. It received a huge response, gathering subscriptions worth £23,114 in just 12 months.

Early in 1922, the Society’s council formed a network of regional branches throughout the country. It planned to hold a conference of branch representatives annually to discuss “the science and practice of pharmacy” and “the general advancement of the objects of the Pharmaceutical Society”.

In 1924, the Society’s bachelor of pharmacy degree was instituted in the University of London Faculty of Medicine and in the following year the School of Pharmacy was admitted as a school of the University. After the Second World War, private schools of pharmacy died out and in 1949 the Society’s school was transferred over to the University of London. The Society’s Pharmaceutical Chemist qualification became a three-year diploma eight years later.

The 1933 Pharmacy and Poisons Act led to Pharmaceutical Society membership becoming compulsory for chemists and druggists. From this point on, registering with the Society and being a member of the Society meant the same thing. However, following another Pharmacy Act in 1953, all pharmacists became known as ‘pharmaceutical chemists’ and the term chemist and druggist fell out of use — those who were originally registered as chemists and druggists were transferred on to the register as members of the Pharmaceutical Society (MPS). Those who had formerly been on the register as pharmaceutical chemists were now Fellows of the Pharmaceutical Society (FPS).

Arguably, the most dramatic change to healthcare in the UK was the arrival of the National Health Service (NHS). Health secretary Aneurin Bevan opened the first NHS hospital, Park Hospital in Manchester (today known as Trafford General Hospital), in 1948. It was the pinnacle of a long-awaited plan to bring free healthcare to all. The NHS meant that, for the first time, doctors, nurses, pharmacists, opticians and dentists were brought together under one umbrella organisation to provide free healthcare services for everyone at the point of delivery. The role of the pharmacist took on a completely different dimension: the public could now get the medicines they needed, when they needed them, without having to worry about how much it would cost.

Changing face of the RPS

Source: Royal Pharmaceutical Society

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s London headquarters in Lambeth High Street between 1977 and 2015

The Scottish and Welsh executives of the Society were formed in 1948 and 1976, respectively. It was in 1977 that the Pharmaceutical Society relocated its London headquarters to Lambeth High Street, where it stayed until May 2015, before moving to its current home in East Smithfield. In 1988, the Queen granted the royal title to the Society.

Throughout its life, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) has been actively campaigning for pharmacy and over the years it has seen clinical pharmacy practice develop, bringing improvements in patient care and medicines optimisation.

In a vote of confidence by the then Conservative government, the 1990 National Health Service and Community Care Act enabled community pharmacy to take on new and broader roles by redefining pharmaceutical services and establishing a government working party to investigate the development of pharmacists.

In 1842, the Society had 951 members; it now has more than 45,000 members. However, the relationship between training and practising as a pharmacist and becoming a member of the RPS has evolved over time, reflecting the nature of the pharmacist’s role, new legislation and changes in the Society itself.

Until 2010, the Society was the regulator for the pharmacy profession as well as the professional body for pharmacy. In September 2010, the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC), a new, independent regulator, took over the regulatory function of the society; RPS membership was no longer compulsory for those wanting to practise as a pharmacist.

Today, students must complete a four-year Master of Pharmacy degree course (first introduced in 1997), followed by a year of preregistration training within a pharmacy workplace. They must also meet the GPhC’s registration requirements before they are able to practise as a pharmacist.

In June 2013, the Society launched its professional recognition programme — the RPS Faculty — open exclusively to RPS members. Through the programme, members can attain post-nominals to demonstrate advanced or specialised practice to their colleagues and the public.

“From its foundation, the Society pursued a strategy of professionalisation designed to transform the drug trade into the profession of pharmacy,” observed Holloway. Pharmacists are a diverse collection of people with hugely differing roles across the healthcare system. The RPS will continue to bring members together and provide them with an identity and a united voice on the issues that affect them.

The Society has evolved through 175 years of rapid social change but the objectives of its founders are still at the heart of what it does — to lead, develop and represent the pharmacy profession.

References

[1] Holloway SWF. Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain: a social and political history 1841–1991. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 1991.