Courtesy of Andrew Godfrey

Andrew Godfrey was training for the 2010 London marathon when he first hurt his back. “I went to the doctor, got some anti-spasmodic drugs and painkillers, and it went away,” he says. But before long the pain returned, leaving him unable to do his job as a fabricator in the steel industry. Next he tried physiotherapy, and improved enough to go back to work. Then in May 2011, 18 months after the first incident: “I was picking up something reasonably light and it felt like my back had broken.”

That was the last time Godfrey worked. He turned out to be seriously ill with multiple myeloma, an incurable cancer of the plasma cells, a type of white blood cell made in the bone marrow. He got his diagnosis three days before he was due to be married, aged 53. “We kept it to ourselves and went ahead. We had a good day,” he says.

Back pain is common, so perhaps it is not surprising that Godfrey’s GP was not too concerned when he originally sought help. By contrast, multiple myeloma is rare. “GPs may only see one or two patients with it in their professional careers,” says Simon Ridley, director of research at the charity Myeloma UK. Ridley acknowledges that there are “plenty of explanations” for the way the disease most commonly presents, for example, with back pain, recurrent infections and fatigue.

GPs may only see one or two patients with [multiple myeloma] in their professional careers

Multiple myeloma is diagnosed in about 4,900 people in the UK each year, and data from 2010–2011 show that only 33% of patients in England and Wales survive for at least ten years after diagnosis. It is especially rare in people aged under 40 years, with incidence rising with age, and is slightly more common in men than women, and in black people than in white and Asian populations.

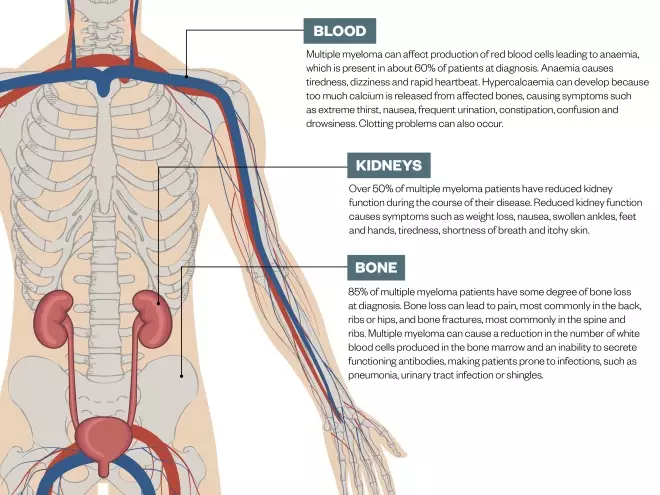

The disease is called ‘multiple’ because it can affect all the sites in the body where bone marrow is normally active in adults — the spine, skull, pelvis, rib cage, the long bones of the arms and legs, and the shoulders and hips — as well as damaging the kidneys (see Figure). The ‘bad’ plasma cells usually release paraproteins: immunoglobulin clones that are incapable of fighting infections, but can clog up the kidneys. Myeloma tends to follow a relapsing and remitting course; there is no cure.

Figure: Symptoms of multiple myeloma

Source: NHS Choices, Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation

Multiple myeloma can affect many parts of the body. The most common symptoms are illustrated above

By the time Godfrey was given a full spinal x-ray, it revealed damage to its entire length, “from neck to coccyx”. That prompted a blood test to look for the telltale paraproteins, and also for anaemia (the disruption of the bone marrow in myeloma prevents the normal production of red blood cells). Godfrey tries not to dwell on the fact that it took almost two years to be diagnosed. “I have been very difficult to treat so I don’t know whether [an earlier diagnosis] would have been better for me, but I can’t change anything,” he says.

And, in one way, he has been lucky. During his time living with the disease, Godfrey has witnessed a revolution in myeloma treatment. “In the past ten years my clinic numbers have doubled or tripled, and that’s not because myeloma has become more common — it’s because the outcomes are much better,” says Graham Jackson, professor of clinical haematology at Newcastle University and one of the doctors who has treated Godfrey. But Jackson’s excitement about the way the field is moving is tempered by the price tag on the new medicines: “We might see improvements stall, even though we’ve got lots of new drugs around, because of the impact of cost.”

In the past ten years my clinic numbers have doubled or tripled, and that’s not because myeloma has become more common — it’s because the outcomes are much better

The old new

The story of the dramatic improvement in the fortunes of myeloma patients starts in 1999 when thalidomide, long despised for its propensity to cause birth defects, was reported to be effective in treating patients with relapsed myeloma[1]

.

Thalidomide disrupts the formation of new blood vessels, which is why it is such a powerful teratogen. Might that same property, the researchers wondered, make it an ideal agent to disrupt myeloma, which relies on a good blood supply to the bone marrow? On the trial, 32% of the relapsed myeloma patients responded to the drug[1]

. This remarkable effect was, in fact, probably achieved through multiple mechanisms of action, including on the immune system, which is why thalidomide is known as an immunomodulatory drug.

Thalidomide was followed by bortezomib (Velcade; Takeda Oncology), a proteasome inhibitor. Proteasomes break down proteins in cells; if the proteasomes do not function, cells die, and as cancer cells are rapidly dividing they have more need of proteasomes than healthy cells. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), England’s health technology assessment body, has approved a number of treatments in the past decade. Bortezomib was approved for use within the NHS as a second-line treatment in 2007. Hot on its heels was lenalidomide (Revlimid; Celgene), another immunomodulatory agent that gained formal approval as a third-line treatment for multiple myeloma in 2009. “Those are the three drugs that have made a dramatic difference in the early part of this century,” says Jackson.

It turned out that they worked best when prescribed together and added to the steroid dexamethasone. “The standard treatment right now is a combination of a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory drug,” says Shaji Kumar, a clinician and myeloma researcher at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Myeloma cells rapidly divide and mutate, and there can be several different clones present in one patient, so the more drugs you hit them with, the better the chance of achieving a response. “We want to try and use a triplet [drug regimen] compared with just a doublet, or at least two classes of drugs compared with just one,” says Kumar.

Courtesy of Shaji Kumar

Shaji Kumar, a clinician and myeloma researcher at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, says the more drugs you hit myeloma cells with, the better the chance of achieving a response

The hope is that these drugs induce a fall in paraprotein levels and, if patients are not too frail, they will then be considered for an autologous stem cell transplant. In this procedure, healthy stem cells are collected from a patient, who subsequently undergoes high-dose chemotherapy (often with melphalan) to wipe out as many of the remaining myeloma cells as possible. Then, to rescue the now dangerously depleted bone marrow, the patient’s own stem cells are returned to the bloodstream. The procedure is intensive and not without risk, and patients will inevitably relapse. “[Nonetheless] a number of studies still show that stem cell transplantation, even in the modern era, improves outcomes,” says Jackson.

A number of studies still show that stem cell transplantation, even in the modern era, improves outcomes

The new new

Jackson’s ‘modern era’ refers to “a whole swathe of new agents coming along which are very exciting” (see table 1). Some of these drugs have brand new mechanisms of action, such as the monoclonal antibody daratumumab (Darzalex; Janssen-Cilag), which binds to the CD38 protein, present in high numbers on the surface of myeloma cells. In one phase III trial, the addition of daratumumab to a regimen of bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed myeloma led to a doubling in progression-free survival after 12 months[2]

. Good results were also seen in a second phase III trial that looked at the addition of daratumumab to lenalidomide plus dexamethasone[3]

.

Courtesy of Graham Jackson

Graham Jackson, professor of clinical haematology at Newcastle University, believes that improvements in myeloma treatment may stall because of the impact of cost

Then there is panobinostat (Farydak; Novartis), which promotes cell death by inhibiting the histone deacetylase enzyme. “As a class it’s been around for a while,” says Kumar, “but panobinostat is the first histone deacetylase inhibitor that has been approved for myeloma.” A phase III trial found that the addition of panobinostat to bortezomib and dexamethasone led to an increase of almost four months in progression-free survival[4]

.

Another new drug is venetoclax (Venclyxto; AbbVie), which has been approved in the United States for treatment of a different blood cancer, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, and is currently undergoing a phase III trial in myeloma. The exciting thing about this agent — a small-molecule inhibitor of BCL-2 that seems to enhance the activities of bortezomib — is that a previous phase Ib study indicated it was particularly effective in a subgroup of patients[5]

. If so, it may prove to be the first targeted therapy available for myeloma patients.

“Venetoclax might work in combination in everyone with myeloma but it particularly seems to be beneficial for the 11:14 translocation group of patients,” says Kumar, referring to an abnormality in which part of chromosome 11 is switched with part of chromosome 14. “We might have a drug that might be the start of personalised medicine for myeloma,” he adds.

We might have a drug that might be the start of personalised medicine for myeloma

Some new agents are derivatives of existing therapies, such as the thalidomide relative pomalidomide. Even when patients have previously been on a drug of that class, these treatments can be very effective. Godfrey, for example, has moved through several different lines of treatment. His disease has never responded sufficiently for an autologous stem cell transplant to be suitable, so he has relied on new drugs coming online to treat each relapse.

They have come not a moment too soon. At one point, after being told by the doctor that he could not have an allogeneic stem cell transplant — which uses stem cells harvested from a bone marrow donor, a much riskier procedure than the autologous version — Godfrey said to his wife, “Is he telling me I haven’t got very long to live?” Shortly afterwards, lenalidomide led to a drop in his paraprotein levels. That drug, in combination with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone, kept him going for 18 months before it stopped working.

After that, he was moved on to pomalidomide. “Everyone reacts differently to the drugs,” says Godfrey. “I think I was the only one in our haematology department who could tolerate it. But, for me, it was like the handbrake being taken off.” He was given 44 cycles of the drug before, last Christmas, his paraproteins started creeping up again. He’s recently been enrolled in the Myeloma UK 8 (MUK8) trial, which is investigating the benefits of adding the new proteasome inhibitor ixazomib (Ninlaro; Takeda) to dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide. It is too soon to know whether he is responding to the treatment.

Clearing the bar

Ixazomib has just received a draft negative recommendation from NICE and so, for now, it will be available only to patients like Godfrey as part of a clinical trial. Daratumumab, also, has been rejected by NICE, even though it is available in the UK to private patients.

The problem, says Jackson, is that “Takeda has to justify not only the cost of the drug for, let’s say, 20 months, but also the fact that patients are on Revlimid and dexamethasone for an extra six months”. That is, if a patient lives longer on this combination, NICE includes the cost of six more months of lenalidomide and dexamethasone in their cost–benefit analysis. “If you do it that way it is virtually impossible for any new drug to be cost effective,” adds Jackson, who believes NICE should reconsider its evaluation model.

Takeda has to justify not only the cost of the drug for, let’s say, 20 months, but also the fact that patients are on Revlimid and dexamethasone for an extra six months

In the meantime, some pharmaceutical companies are giving up. Bristol-Myers Squibb has decided not to submit its new monoclonal antibody treatment, elotuzumab (Empliciti), for approval by NICE. Despite positive phase III results, the company judged that its drug would fail on NICE’s cost–benefit model. This is where Myeloma UK believes it can help. It offers advice to pharmaceutical companies on how best to gather the data they need to go through the NICE appraisal process. “It’s about having UK-generated data for a UK market,” Ridley says.

The drugs are certainly expensive. “The baseline is acquisition cost can be up to £5,000 a month,” says Simon Cheesman, lead oncology pharmacist at University College London Hospital. He thinks that getting the drugs into his pharmacy may rely on pharmaceutical companies giving a heavy enough discount. A spokesperson for Takeda says: “The price of ixazomib reflects the value it provides to patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, who have a poor outlook and limited clinical options.” They added that they have already agreed a patient access scheme with the Department of Health but will re-evaluate it in response to the recent NICE decision.

Courtesy of Simon Cheesman

Simon Cheesman, lead oncology pharmacist at University College London Hospital, says that patients who cannot get onto clinical trials miss out on new multiple myeloma drugs that are not yet available on the NHS

In the meantime, some patients who cannot get onto a clinical trial will miss out. “There may be limited slots or a short period to recruit and we could have a lot of eligible patients,” Cheesman says.

Where drugs have been approved, prescribers are generally restricted as to when they can use them. One particular bone of contention is the use of maintenance therapy, the practice of keeping patients on a drug, usually lenalidomide, after an autologous stem cell transplant. “We know that after a transplant it’s two years on average that the myeloma stays away,” says Kumar. “We can literally double the time from about two years to about four years by using maintenance therapy with lenalidomide,” he believes.

We can literally double [remission] time from about two years to about four years by using maintenance therapy with lenalidomide

Jackson agrees. He is chief investigator in the Myeloma XI trial, which recently released preliminary results demonstrating a 95% increase in progression-free survival (PFS) in myeloma patients receiving lenalidomide maintenance therapy compared with no treatment (median PFS 37 months versus 19 months). Despite the accumulating evidence supporting this indication for lenalidomide, “NICE has not yet really thoroughly looked at that”, says Jackson. “It’s not that it’s rejected it, but it hasn’t said we can do it.” Again, clinicians and patients are left in limbo.

Judgment call

Sometimes doctors simply do not have the information they need to judge which treatment is best at any given stage. “If you purely depend on phase III clinical trial [results] there are limited data in terms of how you sequence these different drugs,” says Kumar.

Ridley agrees: “What we don’t have is sufficient evidence — head-to-head comparatory evidence of all of these combinations. [Without strong trial data] often what is happening is, because of health economic considerations, the cheaper, older therapies are used first.”

[Without strong trial data] often what is happening is, because of health economic considerations, the cheaper, older therapies are used first

Keith Cooper, a health economist at the University of Southampton, who has worked with NICE on assessing myeloma treatments, acknowledges that “the current paradigm is around cost effectiveness, on the basis that they can treat more patients effectively within their budget using the cheapest drugs first”.

But Jackson and other doctors would like more flexibility in how to prescribe myeloma drugs. “Each patient who comes through the door is unique,” he says. Cheesman says it would be useful if NICE would say: “Everybody can have all these drugs once but you can choose which order to give them in.”

And when prescribing a drug, clinicians need to take many considerations into account. For example, there are differences in convenience. Some of the drugs, such as the immunomodulatory agents, are oral. “We give them a bag of tablets once a month, and that’s it,” says Cheesman.

Bortezomib, by contrast, is an injection, either intravenous or subcutaneous. Godfrey recalls having to attend hospital regularly to receive the drug. “I was backwards and forwards to the hospital quite regularly and at the time I wasn’t aware enough to drive,” he says, pointing out that he had to rely on friends to drop him off and pick him up.

The treatments also have side effects, some of which can be serious (see table 1). Cheesman says: “The older drugs — the alkylating agents and steroids — have predictable toxicities,” citing effects such as bone marrow suppression, hair loss and nausea for chemotherapy, and weight gain and mood swings for steroids. “The newer agents have different side effects,” he says.

| Name | Type of agent | Common side effects | NICE recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

Thalidomide | Immunomodulatory | Tiredness, increased susceptibility to infection and bleeding, increased risk of blood clots, peripheral neuropathy, constipation | First-line treatment in combination with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid |

Lenalidomide | Immunomodulatory | Tiredness, increased susceptibility to infection and bleeding, peripheral neuropathy, gastrointestinal effects | Third-line treatment (after two previous treatments) in combination with dexamethasone |

Pomalidomide | Immunomodulatory | Tiredness, increased susceptibility to infection and bleeding, muscle cramps, gastrointestinal effects | Fourth-line treatment (after three previous treatments) in combination with dexamethasone |

Bortezomib | Proteasome inhibitor | Tiredness, increased susceptibility to infection and bleeding, peripheral neuropathy, gastrointestinal effects | First-line treatment where thalidomide is contraindicated, second-line treatment, or as induction therapy before an autologous stem cell transplant. Given in combination with dexamethasone |

Carfilzomib | Proteasome inhibitor | Tiredness, diarrhoea, increased risk of bleeding, shortness of breath, risk of serious heart complications | Appraisal in progress |

Ixazomib | Proteasome inhibitor | Gastrointestinal effects, peripheral neuropathy, swelling of the hands and feet, back pain | Draft rejection |

Panobinostat | Histone deacetylase inhibitor | Tiredness, increased susceptibility to infection and bleeding, diarrhoea, serious heart complications | Third-line treatment in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone |

Daratumumab | CD38 monoclonal antibody | Tiredness, increased susceptibility to infection and bleeding, back pain, infusion reactions | Draft rejection |

Elotuzumab | SLAMF7 monoclonal antibody | Tiredness, increased susceptibility to infection, gastrointestinal effects, peripheral neuropathy, infusion reactions | Company did not submit data for appraisal |

For example, bortezomib can cause damage to the peripheral nerves (peripheral neuropathy), which can be irreversible. Carfilzomib, a newer proteasome inhibitor that is still being appraised by NICE, “doesn’t have that problem but it does have cardiac and respiratory side effects”, says Cheesman. In general, he finds, the immunomodulatory drugs are quite well tolerated, although they carry the risk of serious drops in blood count, which must be carefully monitored. And not everyone gets on with them. Lenalidomide was a struggle for Godfrey: “I was close to thinking, I can’t do this anymore; it’s horrible.”

Perhaps Godfrey’s body was trying to tell him something: these drugs do carry long-term risks. “The one that I think concerns most of us is the risk of getting second cancers,” says Kumar. Jackson agrees that long-term toxicities are a concern, but says, “Even if you take into account some of the risks they’re still heavily outweighed by the advantages.”

The future

Jackson is buoyed by the pace of improvement in outcomes. “In the world of myeloma we veer away a little bit from the word ‘cure’,” he says. “[Nonetheless] a lot of people are dying with their disease rather than because of their disease.” His main concern remains cost. “These new drugs are tremendous but it’s difficult to be too excited when you know that you may not be able to use them.”

In the world of myeloma we veer away from the word ‘cure’. [Nonetheless] a lot of people are dying with their disease rather than because of their disease

Patients such as Godfrey are all too aware of this. He tells an anecdote about a time when he was severely ill with pneumonia in hospital and had been taken off pomalidomide while in intensive care. As he began to recover, the doctors restarted his prescription. “The tablets came back from the pharmacy with the price written on the box and a big question mark on it,” he says.

That gave him pause for thought. “There are people struggling to get NHS-funded drugs and I think about how much is being spent on me,” he says. “I feel very humbled.”

Want to consolidate your knowledge on the pharmacological management of multiple myeloma? Take the

CPD module

now.

References

[1] Singhal S, Mehta J, Desikan R et al. Antitumor activity of thalidomide in refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1565–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911183412102

[2] Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K et al. Daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2016;375:754–766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606038

[3] Dimopoulos MA, Oriel A, Nahi H et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1319–1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607751

[4] San-Miguel JF, Hungria VT, Yoon SS et al. Panobinostat plus bortezomib and dexamethasone versus placebo plus bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1195–1206. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70440-1

[5] Moreau P, Chanan-Khan AA, Roberts AW et al. Venetoclax combined with bortezomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. American Society of Hematology 58th Annual Meeting & Exposition 2016;975. Available at https://ash.confex.com/ash/2016/webprogram/Paper89977.html (accessed July 2017)