Mclean

The UK has one of the most stringent systems of checks and balances on the use of controlled drugs (CDs) in the world. However, experts are warning that, in some cases, the safeguards that were put in place after the Shipman inquiry (see Box 1) are being compromised.

With a wider range of healthcare professionals prescribing CDs, hugely varying reporting rates of incidents involving CDs and a lack of enforcement staff, the whole system is under strain.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC), the health and social care regulator in England, has warned of a “general naivety” regarding the management of CDs among health and social care providers[1]

. In its latest report, published in July 2019, the CQC says that diversion — the transfer from the individual for whom it was prescribed to another person, often to sell or for illicit use — of lower schedule CDs (see Box 2) is “still a concern” and is becoming “increasingly sophisticated”[2]

.

The report added that monitoring of these incidents is “insufficient”, with CD accountable officers (CDAOs) reporting cases of CDs being “grabbed opportunistically over the counter or from easy-to-access shelving”.

Box 1: The Shipman effect

In 2000, then GP Harold Shipman was convicted of using controlled drugs (CDs) to kill 15 patients. This prompted an overhaul of legislation around CDs, with new regulations coming into force in 2007.

Regulations stipulating that healthcare organisations, such as NHS trusts and independent hospitals, must appoint a controlled drug accountable officer (CDAO) have been in place since 2013. CDAOs within an organisation must be a senior manager at the organisation or report directly to a senior manager; be an officer or employee of the organisation; and should not prescribe, supply, administer or dispose of CDs as part of their regular duties.

CDAOs are responsible for establishing and leading controlled drug local intelligence networks and for convening incident panels when serious concerns are raised. All incidents or concerns involving the safe use and management of CDs must be reported to the organisation’s CDAO and details of the incident or concern should be recorded and investigated, where appropriate, using locally agreed procedures.

Incidents reported to NHS England CDAOs are recorded through the NHS England national controlled drug reporting tool.

Lost, stolen or missing

There were almost 3,000 reports of “unaccounted-for losses” of CDs within the NHS in England during 2018/2019[1]

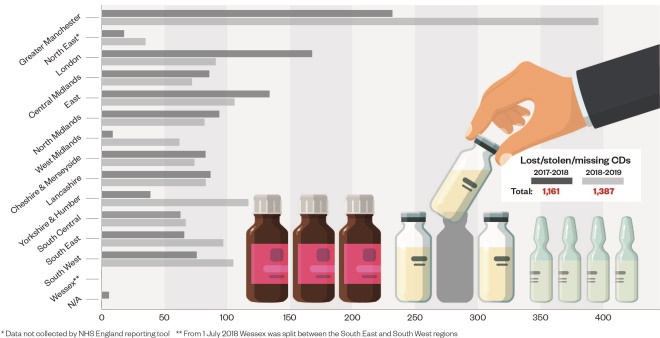

. The Pharmaceutical Journal obtained data under the Freedom of Information Act showing that nearly half of these reports (1,387) involved CDs being lost, stolen or missing, with a wide variation in reporting by region (see Figure).

Figure: unaccounted-for losses of controlled drugs (CDs) reported via the NHS England CD reporting tool, according to region

Source: NHS England

Of course, some of these incidents may be the result of recording errors, but the concern is that some of these drugs will be misused or end up on the black market. An inquiry into the diversion and illicit supply of medicines by the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs in 2016 found that the most frequently diverted drugs were opioids, closely followed by benzodiazepines[3]

.

The introduction of CDAOs was intended to close any loopholes in the system

Raymond Hill, visiting professor of pharmacology at Imperial College London and former chair of the inquiry, says The Pharmaceutical Journal’s figures suggest that the situation around diversion of CDs “has not changed”.

“The introduction of CDAOs was intended to close any loopholes in the system,” he says. “However, no system is perfect and the latest figures show that we should not be complacent about the prevention of opioid diversion.”

He adds that although people should have a “high degree of confidence in safe governance and prescribing practice”, the main problem is that there were too many “responsible people” and that it is very easy for organisations, such as the CQC, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency or the police to say “this isn’t our responsibility”.

Box 2: What is a controlled drug?

Controlled drugs (CDs) are medicines that are regulated by the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001. They are classified based on their benefits when used as a treatment and their harm if misused. The controls are in place to stop drugs and medicines being misused; obtained illegally; or causing harm.

There are five schedules of CDs:

- Schedule 1 CDs have the highest level of control and include drugs that are not used medicinally, such as raw opium and ecstasy;

- Schedule 2 CDs are subject to full CD requirements and include opiates, such as morphine and oxycodone, and major stimulants, such as ketamine;

- Schedule 3 CDs are subject to special prescription requirements and safe custody (with exemptions) and include, for example barbiturates, buprenorphine, gabapentin, midazolam, temazepam and tramadol;

- Schedule 4 CDs are subject to minimal control and include, for example, other benzodiazepines, zolpidem, zopiclone, Sativex, and androgenic and anabolic steroids;

- Schedule 5 CDs have the lowest level of control and contain preparations of CDs, such as codeine and morphine which, owing to their low strength, are exempt from virtually all CD requirements other than retention of invoices for two years.

Public diversions

Jon Hayhurst, head of pharmacy, and CDAO and medication safety officer at NHS England and NHS Improvement South West, says diversion by patients and members of the public “goes on a lot”, and particularly with Oramorph (morphine sulphate; Boehringer Ingelheim), which is a Schedule 5 drug.

“It’s got the lowest level regulation of all of the CDs and yet the number of harms is quite significant — it is one of the [CDs] most commonly diverted by patients and members of the public [because] there’s so little control over it.

“Just [in 2019], I’ve heard of three accidental deaths involving Oramorph — two were where Oramorph belonging to one patient ended up in the home of someone else.”

In order to address diversion by patients, Hayhurst says that more effort needs to be made to tackle overprescribing of CDs. “There are a lot of CDs going out there. The biggest thing we can do is only prescribe and supply CDs to patients who really need them.”

However, the national picture on the scale of diversion of CDs is still unclear.

In its July 2019 report, the CQC recommended that nominated CD leads “must have oversight of the use of [CDs] and follow up any unusual use to assure themselves that the arrangements for [CDs] are safe”.

The number of incidents reported needs to be seen in the context of the volume of controlled drugs dispensed

Reporting of unaccounted-for losses of CDs is getting better, with the data obtained by The Pharmaceutical Journal showing a 19% increase in reporting of lost, stolen or missing CDs over the past year, up from 1,161 incidents in 2017/2018 to 1,387 in 2018/2019.

However, NHS England’s reporting tool is very new and there are still large regional variations in reporting rates. For example, data for the West Midlands show that 62 incidents involving lost, stolen or missing CDs were reported in 2018/2019 — just 16% of the number reported in neighbouring Greater Manchester (396).

However, Greater Manchester is the region where the former GP Harold Shipman practised, and it developed and implemented the NHS England CD reporting tool in 2014, while some areas only started using it fully in 2018

[2]. As a result, these figures reflect that action has been taken more rapidly in this area than in other regions of England, explains Karen O’Brien, a CDAO in the Greater Manchester area. “Our use of this tool is, therefore, more deeply embedded than elsewhere,” she says.

“We also need to remember that we have around 700 pharmacists who are dispensing circa 15 million prescription items each month in Greater Manchester, so the number of incidents reported also needs to be seen in the context of the volume of CDs dispensed,” she adds.

“We have also developed a strong culture of reporting every incident using the tool, in order to encourage openness and learning from every incident.”

O’Brien says the majority of reports they receive in Greater Manchester are categorised as‘lost’ or ‘missing’, rather than ‘diversion’, and that most cases of diversion are one-off incidents. This, she believes, implies that people using the tool are learning from these incidents because the method or circumstances are not often repeated.

Tip of the iceberg

Mike Beard, a CD liaison officer in Greater Manchester, says that many people do not report incidents out of fear. He gives an example of two major hospitals in Greater Manchester, both of which reported incidents over a three-month period.

“Wythenshawe [reported] 420 incidents, while Bolton Royal [reported] 8 incidents. You might ask what’s going on at Wythenshawe, but that’s not the right question — Wythenshawe reported every single incident. The question is, what’s going on at Bolton Royal?”

There is diversion everywhere — we’ve seen unusual drug activity in every organisation we’ve put the system into

Hayhurst agrees that there is “huge variation” across the country when it comes to reporting and that many incidents are not reported in a timely way. He stresses that healthcare professionals should report all incidents, no matter how trivial they seem.

However, he highlights that it is difficult to compare areas since CDAOs in different regions have different levels of resource, which means the amount of time they can spend reviewing incidents is variable.

“I have colleagues who have really, really small teams and they tell me they just look for the [incidents] that are really bad and deal with those.

“But that means that [with] all the ones where they are not concerned, they may not reply, and if you never hear anything back [from a report you’ve made] you may be less likely to report in the future.”

Jonathan Kerr, director of Rx Info, the company behind the abusable drugs investigation software ‘ADIoS’, which monitors drug use and flags any statistically unusual variation, believes diversion of such drugs to be a significant, and current, problem.

“When you start looking under stones you will find it — there is diversion everywhere — we’ve seen unusual drug activity in every organisation we’ve put the system into.”

He agrees with the CQC in that the problem is often linked to drugs with fewer controls.

“The drugs that come up time and time again are those that are easier to be misappropriated.”

But CDAOs say the problems are not uniform across the country. Sue Ladds, chief pharmacist and CDAO at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, says that although lost or missing CDs are regularly reported in large hospitals, the vast majority are isolated occurrences of an individual tablet or ampoule of something found to be missing from a pack during a routine stock check on a ward.

“In some cases, for example where there may have been a record-keeping omission, it is not possible to identify a reason for the discrepancy,” she says. “These are classified as ‘unexplained losses’ and are reportable to the CDAO, but are most likely simple process errors, [with] no other reason to suggest deliberate diversion.”

Ladds says that, in the past six years as a CDAO, she has only come across two proven cases of deliberate diversion of hospital CD stock by healthcare professionals — both of which were Schedule 4 and Schedule 5 drugs, which are not subject to the same level of regulatory control as those in Schedule 2.

“All of the variances identified and investigated to date have been explained by clinical reasons, for example an individual patient needing a high dose or having a prolonged stay on a particular ward.”

This debate will continue until more clarity exists around the frequency and seriousness of CD diversion. While Greater Manchester is strides ahead, O’Brien believes that reporting rates are increasing across all regions of England, and, in time, other regions will inevitably catch up.

“We do all share our experiences with each other and I believe the message of an improving culture is growing rapidly across localities,” she says.

References

[1] Care Quality Commission. 2019. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20190708_controlleddrugs2018_report.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[2] Care Quality Commission. 2018. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20180718_controlleddrugs2017_report.pdf (accessed November 2019)

[3] Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. 2016. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/580296/Meds_report-_final_report_15_December_LU__2_.pdf (accessed November 2019)