MAG / Shutterstock.com

John Amory, a researcher in male reproduction at the University of Washington in Seattle, is a self-confessed “history buff”. He was reading an article about the history of andrology — the male counterpart to the field of gynaecology — when he came across a mention of a 1960 study in which a novel contraceptive was tested on male prisoners, with good results. He was intrigued. “I thought, ‘that’s interesting, I wonder how it worked’.”

He did some digging and found that further studies of the compound, called WIN 18,446, in the general population did not go so well: those men suffered severe side effects. The main difference was that prisoners did not have access to alcohol. Something about WIN 18,446 caused those who took it to have a bad reaction to drinking.

The reaction people had to alcohol while taking WIN 18,446 reminded Amory of the drug disulfiram, sometimes used to treat alcoholics because it blocks an enzyme – aldehyde dehydrogenase – which helps to break down alcohol in the liver. Shortly after finding out about WIN 18,446, Amory heard a talk by a colleague about the role of vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid in sperm production, and how its formation relies on aldehyde dehydrogenase. “It was like a eureka moment,” he says. “I thought, ‘I bet those drugs were blocking the aldehyde dehydrogenase that’s involved in testicular retinoic acid biosynthesis’.”

It was like a eureka moment. I thought I bet those drugs were blocking the aldehyde dehydrogenase that’s involved in testicular retinoic acid biosynthesis

That was ten years ago. Since then, Amory and his eight-strong team of researchers have been working on developing a drug that selectively shuts down retinoic acid production within the testes, but not in the liver or elsewhere in the body. It has been a long and complicated journey, and it’s not over yet.

Source: Courtesy of John Amory

John Amory, at the University of Washington in Seattle, is trying to develop a male contraceptive that inhibits sperm production by blocking retinoic acid synthesis in the testes

Amory is hoping that his work will attract an industry partner to help take the drug to market. “It takes a lot of resources, a lot of expertise, and a lot of money to test these things sufficiently to get approval,” he says, admitting a newfound respect for drug companies, likening the process of developing a specific inhibitor to “trying to pick a lock”.

He is not alone in hoping the pharmaceutical industry will take an interest in developing a contraceptive for men. Diana Blithe, director of the National Institutes of Health’s male contraceptive development programme, based in Bethesda, Maryland, remembers a time when there was some interest from big pharmaceutical companies. “There used to be a couple of organisations that were pursuing male contraception, but then they each merged with a different company. After the mergers, decisions were made to no longer pursue that area,” she says. Her department attempts to plug that gap but, she acknowledges, “our plug is tiny by financial standards to what industry might consider doing”.

There’s some political concern about male methods taking away from female control of their own reproduction

Perhaps the potential market is small because men are simply not interested in more contraceptive options. After all, women are the ones who bear the brunt of a contraceptive failure, and some people believe that the control should stay firmly in their hands. “There’s some political concern about male methods taking away from female control of their own reproduction,” says Stephanie Page, an endocrinologist specialising in the role of androgens, also at the University of Washington.

But evidence suggests that men are interested. A 2002 poll of more than 9,000 men across four continents found that, on average, 55% would be willing to try a hormonal contraceptive. And one male contraceptive option currently in development in the United States, called Vasalgel, has received interest from more than 31,000 men and women.

Pharmaceutical companies will be aware that reproduction is a particularly litigious area. For example, if a couple has a child with a birth defect subsequent to one of the partners having been on a contraceptive, it is hard to prove whether or not that birth defect was caused by the contraceptive or something else. “I think that the pharmaceutical companies look at the field and say well, it’s true people make money selling female hormonal contraceptives, but they also get sued a lot,” says Amory.

Couples share every aspect of their lives so why not share contraception?

As far as Page is concerned, it is about choice: “There are women who can’t tolerate hormonal methods for a variety of reasons and so giving couples choices is important.” Plus, many men already use contraception, but condoms are “horribly ineffective in real-life use for contraception” and vasectomies are not always reversible. As Lee Smith, principal investigator at the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health at the University of Edinburgh, puts it: “Couples share every aspect of their lives so why not share contraception?”

Getting hormonal

There are two main routes for male contraceptive development: hormonal and non-hormonal. Hormonal contraceptives are familiar to us from the female pill, whereas a non-hormonal method is anything “that does not affect the hormone system of the body”, says Smith.

The World Health Organization (WHO) funded two seminal studies, published in the 1990s, which provided proof of concept that a male hormonal contraceptive along the lines of the female pill could work[1],[2]

. These studies relied on giving men high doses of testosterone, about twice the normal physiological level. “We give men testosterone, the signals from the brain say we have enough testosterone, we don’t need you to make any more, the testicle stops making testosterone,” explains Page. Sperm require high levels of testosterone in the testicle to reach full maturation.

The problem was that the testosterone approach did not work in everyone. A majority of men who took part in the study ended up with sperm counts below the 1 million sperm per millilitre normally required to get a woman pregnant, but “they never really got to the 95% to 100% efficacy that was necessary for marketing”, says Amory. Then there is the fact that there are side effects for men receiving high-dose testosterone, including weight gain, toxicity for the heart, liver and kidney, and a potential increased risk of prostate cancer.

Researchers went back to female contraception for inspiration, adding a progestin — a synthetic analogue of the hormone progesterone — to the androgen (testosterone). “In men, if you give them progesterone, which is something they’re not expecting to see very much of and certainly not constantly, then it causes their testes to stop making testosterone,” says Blithe. Of course, men need circulating testosterone to support normal functions, including libido and ejaculation, “so you have to replace that testosterone in the blood to keep all those functions working”. But here we are talking about physiological levels of testosterone, which should eliminate the risk of side effects.

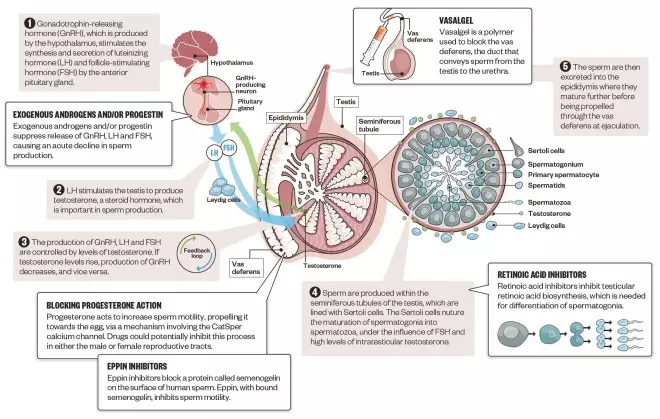

Mechanisms of male contraceptives

Source: Infographic: Alisdair Macdonald; editorial adviser: John Amory

Both hormonal and non-hormonal methods of male contraception are under development. Hormonal methods disrupt the normal hormonal feedback loop that controls sperm production, while non-hormonal methods interfere with spermatogenesis, sperm motility or passage out of the testis

However, the reality is not always that simple. A recent phase II study of a progestin–androgen combination, sponsored by the WHO and CONRAD – a not-for-profit organisation based in Arlington County, Virginia – was halted after concerns about a higher number of reported side effects than expected, including depression and an increased sex drive.

If a hormonal contraceptive for men is to reach the market, the most important thing will be getting the right combination. This means considering both side effect profile and mode of delivery, and this can be complicated. For example, testosterone, as it is produced by the body, cannot be taken in pill form since it is metabolised too quickly. So it has to be modified, but that can carry risks. The first oral testosterone introduced, methyltestosterone, was associated with liver toxicity because of the addition of the methyl group, says Page.

The same goes for progestins. Although it is more common to get progestins in oral form, different progestins have different side effect profiles depending on how selective they are at targeting the progesterone receptor.

Blithe and Page are working on a new combination and are about to embark on a phase III trial in 300 couples. In this case, the progestin is a relatively new compound, Nesterone, and it is only available in a transdermal preparation. They’re combining this with a testosterone in a gel formulation.

Courtesy of Stephanie Page

Stephanie Page, an endocrinologist also at the University of Washington in Seattle, believes that the first male hormonal contraception on the market will be an implant, transdermal patch or long-acting injection

Page believes that “the ‘male pill’ is not going to be the first hormonal contraceptive on the market”. “It’s either going to be an implant, transdermal, or a long-acting injection,” she adds.

But the male pill is still an option. She and Blithe are also working on a compound, dimethandrolone undecanoate (DMAU), which seems to work as both an androgen and a progestin, meaning men could potentially take just one drug to get the effects of a combined contraceptive[3]

. Although their work is still in the early stages, this can be given in an oral form.

We know so much about hormonal replacement in both men and women, and there’s been a lot of trials showing that this works

There are advantages to a hormonal approach, the main one being that researchers have amassed a wealth of knowledge about these methods. “We know so much about hormonal replacement in both men and women, and there’s been a lot of trials showing that this works,” says Blithe.

But the fact that they have been around for a while means that hormones have ended up with a bit of an image problem. “You don’t get the good press on hormonal methods,” says Blithe. And certain men would not be able to take testosterone; for example, athletes could open themselves up to accusations of doping.

Non-hormonal approaches

Meanwhile, non-hormonal approaches are catching up. Amory and his team are currently testing the compounds they have designed to selectively block the enzyme involved in testicular retinoic acid synthesis in mice. They have established that the drugs are blocking retinoic acid production and are “currently testing the mice to see what the impact of this is on their sperm production”.

Amory believes this approach could have several advantages: “The drugs are oral, they don’t interfere with testosterone production.”

Also, because they would turn off sperm production completely, “if a man missed a dose, it’s not like sperm production comes roaring back in a day, there’s a little bit of tolerance for error”. And men can now check whether they are producing sperm with a home testing kit, partly developed by Blithe, called SpermCheck. This means they could be sure that the drug is working before relying on it for contraception.

Courtesy of Diana Blithe

Diana Blithe, director of the National Institutes of Health’s male contraceptive development programme, based in Bethesda, Maryland, is about to embark on a phase III trial with Stephanie Page testing a combined hormonal contraceptive in a gel formulation for men

Another promising target is eppin, a protein on the surface of human sperm. In a landmark study[4]

in 2004, Michael O’Rand, a reproductive biologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and colleagues showed that immunising primates with eppin — leading to the production of antibodies against the protein — caused seven out of the nine male monkeys tested to become infertile. Five out of ten of them recovered their fertility once immunisation was stopped. Immunocontraception is not considered the best approach in humans so O’Rand is now developing a specific inhibitor of eppin, and has formed a start-up company, EppinPharma Inc, to advance its commercialisation. Without interest from the big pharmaceutical companies, “academic research and university start-ups were the only alternatives,” he says.

Potential new targets for male contraceptive development are being identified all the time. Smith works on the genetics of male infertility and testosterone production. “We often identify genes that when mutated lead to male infertility,” he says. His group simply identifies the targets, but if the function of those genes could be blocked, he says, that “becomes a potential contraceptive for all men”.

Some targets could even be used to develop ‘unisex’ contraceptives — one drug that would work in both women and men. Melissa Miller, a postdoctoral researcher in reproductive health at the University of California, Berkeley, has been involved in work identifying the mechanism by which sperm are propelled towards an egg[5]

. “Sperm, when they are deposited into the female reproductive tract, are still in an immature state and are unable to fertilise the egg,” Miller explains. Progesterone, released from the egg, effects a change on the sperm, making it “swim with much stronger force”.

Miller and others have identified that this process works through a channel on sperm called CatSper; if men lack proper CatSper function they are infertile. “If we were to develop a way to block the progesterone activation of sperm, we would also inhibit its ability to reach and fertilise the egg,” she says. Theoretically, this could happen in either the male or female reproductive tract.

If a woman takes a contraceptive there’s actually a health benefit for her — she could die in childbirth still

Some non-hormonal approaches do not involve drugs at all. Probably the most promising of these are polymers used to block the vas deferens, the duct that conveys sperm from the testicle to the urethra that is targeted in a vasectomy. Vasalgel, which was developed off the back of research in India with a method called RISUG, is one of these formulations. The hope is that it will be similar to a vasectomy, but more reversible. Linda Brent, deputy director of the Parsemus Foundation, a US non-profit organisation that is funding its development, says Vasalgel has already been tested in rabbits, with good results, and it is hoped that the first human trial will be launched later in 2016. She believes that if human trials are successful, Vasalgel could be available as early as 2018. “However, it depends mainly on the regulatory agencies, and how quickly approvals for the new product can be obtained,” Brent adds.

Shooting in the dark

Regulatory approval is one of the major reasons why these agents may not make it to market. For a start, male contraceptives are a special case. “If a woman takes a contraceptive there’s actually a health benefit for her — she could die in childbirth still,” Page says. This is not the case with a man.

Then, the regulatory framework has changed since the female contraceptive pill was first approved in 1957. “The male methods we have are way better than the female pill was when it was introduced,” says Blithe. Page agrees. “These things work, there’s no question about that, but they’re not 100%, with zero side effects.”

One of the things she and Blithe are trying to do with their phase III study is to get a sense of what the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the US medicines regulator, would require in terms of safety data in order to approve a male contraceptive. “We’re going to go to the FDA with our relatively small trial and say ‘what is going to take for us to get this to the next step?’” She believes that if some guidelines can be established, pharmaceutical companies are much more likely to show interest.

Many groups worked on contraceptive research in the 1990s, myself included, but funding from pharma and government was not forthcoming

Meanwhile, some researchers are being put off by the lack of funding. Valerie Ferro, a lecturer at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, used to work on possible vaccine approaches for male contraceptives, but has moved on to focus on other areas. “Many groups worked on contraceptive research in the 1990s, myself included, but funding from pharma and government was not forthcoming,” she says.

The Parsemus Foundation, set up to advance innovative and neglected medical research, is one not-for-profit organisation that is trying to address this. As well as developing Vasalgel, it gave a start-up grant to another US non-profit, the Male Contraception Initiative, which is the only not-for-profit that is solely focused on the development of new male contraceptives, according to executive director Aaron Hamlin.

But interest from big pharmaceutical companies could make all the difference in terms of how quickly a new male contraceptive could reach the market. Blithe says she is “not overly optimistic about a timeline with our limited resources”. She believes that “it might go faster if a company was making it its primary mission”.

Without that push, male contraceptives could be as near, and as far, as ever, Amory fears. “The joke in the field is we’ve been five to ten years away from a male contraceptive for about 30 years.”

References

[1] World Health Organization Task Force on Methods for the Regulation of Male Fertility. Contraceptive efficacy of testosterone-induced azoospermia in normal men. The Lancet 1990;336:955–959. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92416-F

[2] World Health Organization Task Force on Methods for the Regulation of Male Fertility. Contraceptive efficacy of testosterone-induced azoospermia and oligozoospermia in normal men. Fertility and Sterility 1996;65:821–829. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)58221-1

[3] Surampudi P, Page ST, Swerdloff RS et al. Single, escalating dose pharmacokinetics, safety and food effects of a new oral androgen dimethandrolone undecanoate in man: a prototype oral male hormonal contraceptive. Andrology 2014;2:579–587. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2014.00216.x

[4] O’Rand MG, Widgren EE, Sivashanmugam P et al. Reversible immunocontraception in male monkeys immunized with eppin. Science 2004;306:1189–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.1099743

[5] Miller MR, Mannowetz N, Iavarone AT et al. Unconventional endocannabinoid signaling governs sperm activation via the sex hormone progesterone. Science 2016;352:555–559. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6887

You may also be interested in

Provision of progestogen-only pill with emergency contraception in community pharmacy improves ongoing contraception use

Government group recommends reclassifying progestogen-only pill as an OTC medicine