Jatinder Harchowal

Open access article

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has made this article free to access in order to help healthcare professionals stay informed about an issue of national importance.

To learn more about coronavirus, please visit: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/pharmacy-guides/wuhan-novel-coronavirus

Source: Jatinder Harchowal

Jatinder Harchowal, chief pharmacist at NHS Nightingale Hospital London

A week before the UK lockdown began, on 16 March 2020, a report published by the Imperial College London COVID-19 Response Team predicted that even with the “optimal” mitigation scenario, the pandemic would result in an eight-fold higher peak demand on critical care beds than the available surge capacity in the UK.

As the daily number of new cases of COVID-19 began increasing, a decision was taken to construct temporary field hospitals across the UK, with thousands of beds ready to take COVID-19 patients, if and when they were needed.

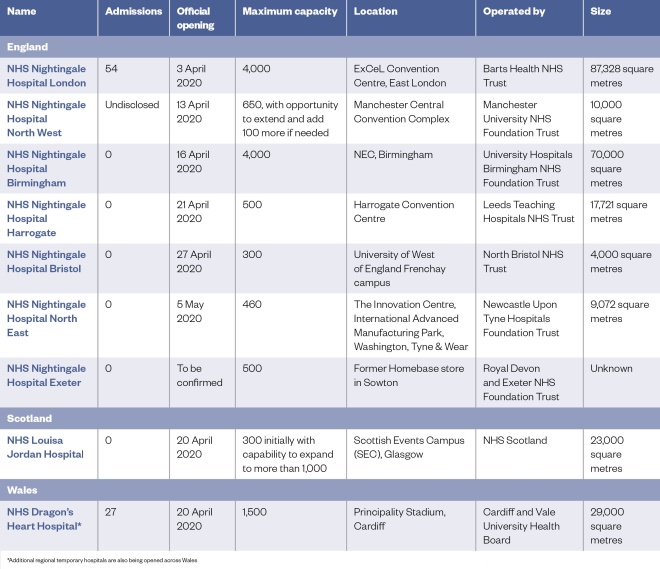

The first of these hospitals was the NHS Nightingale Hospital London, which was officially opened on 3 April 2020 at the ExCeL Conference Centre. Further field hospital sites were then announced in Manchester, Bristol, Birmingham, Harrogate and Exeter, as well as in Scotland and Wales (see Table).

Setting up these hospitals took an extraordinary effort, involving the military, volunteers and scores of staff from surrounding hospitals. It took just nine days to fit the NHS Nightingale Hospital London with 4,000 beds across its 80 wards.

To date, this extra capacity has barely been needed. Indeed, on 4 May 2020, it was announced by a spokesperson for 10 Downing Street that, starting with London, many of the NHS Nightingale hospitals would be “wound down” owing to a lack of patient demand.

However, this does not detract from the achievements of hospital pharmacy teams across the country who have written an astounding piece of NHS history, and shown enormous courage and spirit while doing it.

Table: The COVID-19 hospitals in numbers

Setting up

Jatinder Harchowal, chief pharmacist and head of quality improvement at the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust in London, says he “didn’t think twice” about his decision when asked to head up the pharmacy team at the NHS Nightingale Hospital London.

“We were in the midst of the rising cases [of COVID-19] and we knew the importance of a project like this — I saw it as a huge opportunity.”

The pharmacy team model developed by Harchowal and his team involves having one critical care pharmacist on duty, accompanied by a support team who, in time, could be developed and trained to take on increasing responsibilities. Harchowal is keen that these pharmacists would be able to take this training back to their organisation, once the field hospitals are no longer needed.

Tim Banner, pharmacy lead at the Dragon’s Heart Hospital, based at the Principality Stadium in Cardiff, Wales, says that he decided to recruit pharmacists and technicians with more experience who were able to hit the ground running and were confident in making the necessary decisions.

“We’ve recruited around 4 pharmacists, a couple of technicians, and … around 16 or 18 band 2 support staff as well,” he says.

“But the challenge is how you train up new staff in [what is] a major departure from what our normal comfort zone is within secondary care pharmacy.”

The pharmacy team at NHS Louisa Jordan Hospital in Glasgow, Scotland, is also small, starting with just the pharmacy lead, Susan Roberts, and eventually expanding to a core team of four pharmacists pulled from various pharmacy sectors. However, Roberts has also harnessed the remote expertise of others, including recently retired pharmacists, who have decades of experience in procurement and governance.

Despite the small size of the team, Roberts maintains that it has been a “Scotland-wide effort”.

“The Scottish governance setup is quite different from the England Nightingale set up — the pharmacy services are hosted by another health board, so that took a little bit of working out, and we had quite a bit of support for that from Scottish government and Health Improvement Scotland.”

New challenges

There’s no blueprint for how to set up one of these hospitals. There’s no ‘how to guide’ for setting up a pharmacy department in two weeks

Setting up an entire hospital in a matter of days comes with many challenges.

“There’s no blueprint for how to set up one of these hospitals,” says Banner. “There’s no ‘how to guide’ for setting up a pharmacy department in two weeks.”

Issues with personal protective equipment (PPE) and medicines shortages have been widely reported in recent weeks; however, for Banner, sourcing enough oxygen was the predominant challenge at Dragon’s Heart Hospital.

The Welsh hospital is currently spread across four levels of the stadium. The pharmacy has been constructed in one of the hospitality kitchens on level five, but there are plans to develop the main pharmacy base on level three, closer to pitch level, where more patients can be accessed.

“We have got a [vacuum insulated evaporator (VIE)] — the big oxygen tanks on site — but they’re only for the pitch-level tents. So, we’re using concentrators and cylinders for level five at the moment.”

Sourcing the required quantity of pumps and syringe drivers has also been difficult; Banner and his team have had to work with the Dragon’s Heart medicines management nurse to find drugs that are suitable for gravity infusions — something that is no longer done frequently in secondary care, he explains.

Medicines storage is also a challenge in a temporary hospital setting.

“We’ve ended up having to buy a significant number of controlled drugs cupboards to put into nurses’ stations,” says Banner.

“We [also] haven’t got patient lockers, so we’ve had to go back to the old-fashioned way of delivering medications on medicines trolleys — I think we’ve got 130 medicine trolleys on site; the logistical challenge of managing those is huge.”

Roberts says that, in Scotland, as well as logistical issues around procurement, there were physical challenges associated with being set up in an exhibition centre.

“The sheer scale of it — our biggest hall is 500 beds — how are we going to make sure that the patients have access to medicines in a timely fashion?”

In London, Harchowal and his team made an early decision to have all critical care drugs in a ready-to-use format, such as prefilled syringes or bags containing the necessary medicines, to make it as easy as possible for their nursing and medical colleagues to administer the medicines to potentially high numbers of patients. Their efforts, aided by the support of pharmacy manufacturing units across London, have paid off: “So far, we’ve managed to provide all of the doses for every patient since day one,” says Harchowal.

We were able to take it through a rapid improvement review and agreement in the space of ten days — I think that’s a world record

Another change the pharmacy team adopted in the London Nightingale hospital was a move to a new critical care drug chart.

“We realised quite quickly that we needed to amend the critical care drug chart and make it fit for purpose here,” he explains.

“We were able to take it through a rapid improvement review and agreement in the space of ten days — I think that’s a world record .”

“I don’t know if that would have ever been possible in any organisation previously.”

Low admissions

Ruth Murdoch, head of pharmacy at NHS Nightingale Hospital North West, based in Manchester, said that the hospital, which is providing oxygen therapy, general medical care and rehabilitation to patients, had not been as busy as expected.

“The ethos from the start [was that] we’re building this; it may not be needed, but we’ve got to make sure the facility is ready if it is needed,” she explains.

“The majority of staff that are working with us are not full time — we’re scaling our staff to the demand that’s there, and we’ve trained people so we can pull them in if we need to.”

A spokesperson for the Manchester hospital would not give specific numbers for patient admissions but said that the hospital had “had a handful of patients at any one time so far”. They added that “a faster flow” of referrals was expected as the rest of the NHS system in the North West moved back towards “business as usual”.

At the NHS Louisa Jordan Hospital, the team is still awaiting its first patient, despite being operational since 20 April 2020.

“We haven’t had any patients yet,” explains Roberts.

“We know that from when we started to build this hospital we’re now in a good place and the first waves [of COVID-19] have been flattened earlier than hoped — so right now that urgency and that need isn’t the same as it was.”

In the Dragon’s Heart Hospital, 27 patients have been admitted since 28 April 2020 and 3 have been discharged home — nowhere near the 1,500 patient capacity.

“The trajectory of COVID-19 hasn’t really gone as we potentially thought it was going to at the end of March,” says Banner.

“There wasn’t really a huge need for patients to be transferred there when we were still building it up.”

Going forward

The bureaucracy has been totally stripped away from the process and clinicians have just been allowed to do what needs to be done

Despite the low numbers of patients they are treating, pharmacists say they have learnt a lot from the experience. One take-home message from the field hospitals is how quickly decisions can be made when the situation requires it.

“The bureaucracy has been totally stripped away from the process and clinicians have just been allowed to do what needs to be done to get the job done to set this up,” explains Banner.

Roberts believes there are already a lot of lessons to be learnt from the pandemic.

“The barriers that have been there for so long just suddenly evaporate because you’re placed in that situation. I think, as a profession, there will be a lot more collaboration — a lot more thinking, ‘we made all these changes because of COVID-19, why would we go back’?”

In Manchester, Murdoch says working in NHS Nightingale Hospital North West has taught her the importance of building relationships in person and not just through a computer.

“I work in a massive trust and we spend a lot of time emailing people … [but] walking things through and getting decisions made face-to-face is something that we need to learn to continue in a post-COVID world,” she says.

For many of the pharmacists involved in the COVID-19 field hospitals, the experience of dealing with the pandemic could be the only time they face such a challenge in their careers.

“Speaking on behalf of everyone who’s working in the pharmacy department here at Nightingale — it has been one of the most rewarding and positive experiences of our careers,” says Harchowal.

“It has felt really collaborative and genuinely non-hierarchical; a real team approach focused on improving the care for our patients every single day. It’s been hard work … but the people here at Nightingale have been nothing but an absolute delight to be with.”

“Because staff are all in PPE, I think it takes away some of the barriers of who anybody is — you’re there valued as a healthcare member and a member of that team,” he adds.

Banner says he is keen not to lose the learning that has been generated during his time at the Dragon’s Heart Hospital.

“The flexibility of the whole team has been absolutely amazing. We’ve gone to a seven-day working pattern in about two weeks … it has allowed us to modernise our service very, very rapidly. I hope we don’t lose it when this is all over.”

Roberts says that the set-up of the NHS Louisa Jordan Hospital represented “human nature at its finest”.

“The energy and experience of the set-up was an absolute privilege [to be a part of], although you have to remember we’re doing this for a terrible reason, and we hoped that we’d never have to open the hospital … that team spirit in action, that’s probably the first time I’ve ever seen it executed to that level.

“I’ll never see that again in my career, I don’t think. I’m really proud of my profession.”