Nick Oliver

The most costly drug currently available on the NHS is about to come off patent. Humira (adalimumab; AbbVie) costs the health service in Britain in excess of £500m per year and its patent expiry will offer competitors the opportunity to bring their own versions of the drug to market at potentially lower prices.

As these new versions — known as ‘biosimilars’ — become available, the potential savings on this blockbuster drug are vast. Nearly 16,000 items of adalimumab were prescribed in England in 2017, and NHS chiefs are eagerly awaiting the October 2018 expiration date.

Simon Stevens, chief executive of NHS England, is looking to save between £200m and £300m by 2021 across the board on biologics. Adalimumab will be a significant contributor to these savings, along with an estimated ten important biologics due to come off patent by 2021 (see Table 1).

In 2017/2018, adalimumab cost the NHS in England £462m, of which £436m was spent on the drug’s use in hospitals. In Scotland, the current spend is in excess of £40m per annum, and in Wales, adalimumab cost secondary care £15m in 2016/2017.

Source: Courtesy of British Generic Manufacturers Association

Warwick Smith, director general of the British Biosimilars Association and British Generic Manufacturers Association, says that adalimumab will be a significant contributor to the £300m savings on biologics being sought by NHS England

Infliximab, a drug used for several inflammatory conditions, is an example of how much can be saved. When Janssen Biologics’s patent for Remicade expired in 2015, the average cost of infliximab per defined daily dose dropped by 59%[1]

. National uptake of best-value biologic infliximab, as of May 2018, was 89%.

By introducing competition you increase choice for clinicians and patients

However, experts assure that the benefits of biologic patent expiry are not just financial.

“By introducing competition you increase choice for clinicians and patients,” says Smith.

“Although the medicine is not clinically different from the originator, there might be enhancements, such as improved delivery mechanisms and support packages which go with the product, which clinicians can choose if it’s in the interest of the patient,” explains Warwick Smith, director general of the British Biosimilars Association and the British Generic Manufacturers Association.

At the Clinical Pharmacy Congress in London on 27 April 2018, Keith Ridge, chief pharmaceutical officer for England, said that biosimilars were “a real opportunity for the NHS”, not just because of the savings but because they allow patients greater “access to life-changing medicines”. He added that pharmacists in particular were critical in getting the best value from these medicines.

Source: Jeff Gilbert

At the Clinical Pharmacy Congress in April 2018, Keith Ridge, chief pharmaceutical officer for England, said that pharmacists in particular were critical to getting the best value from biosimilars

With NHS leaders predicting such benefits, hospital trusts, commissioners, pharmacists and other healthcare professionals are being urged to ensure that they are ready to switch to the best-value biologic once adalimumab comes off patent. But what potential challenges could arise when making the switch and, in particular, what concerns could patients have at the prospect of switching over when the rationale is predominantly financial?

Panel 1: What are biologics and biosimilars?

Biological medicines, or biologics, have revolutionised treatment for many patients living with chronic conditions, such as diabetes, autoimmune disease and cancer. Derived or manufactured from a living source, biologics work by targeting specific chemicals or cells involved in the body’s immune system response[2]

.

A biosimilar is a biologic that is highly similar to an existing, already approved biologic (the ‘originator’). Although not an exact copy, the biosimilar has no clinically meaningful differences to the originator and is approved according to the same standards of pharmaceutical quality, safety and efficacy that apply to all biologics.

Commissioning and procurement of biologics

Although treatment decisions should primarily be made on the basis of clinical judgement for individual patients, the biosimilars themselves — most of which are used in secondary care — are also chosen on the basis of the overall value proposition offered by individual medicines, according to NHS England. This means that if more than one treatment is suitable, the best-value biologic should always be chosen.

“The NHS England Commercial Medicines Unit (CMU) typically runs regional procurement and tender exercises and the successful products will then go on to a framework agreement,” explains Smith.

The CMU is currently scheduling the procurement process for adalimumab after the loss of Humira’s patent exclusivity, which is expected in October 2018.

The adalimumab biosimilars approved for use in the UK, but still subject to the procurement exercise, are: Amgevita (Amgen), Hyrimoz (Sandoz) and Imraldi (Samsung Biogen). The products will be reviewed on an ongoing basis as information becomes available, but NHS England says that it is clear that these products will have differences in terms of their excipients and administration devices[3]

.

The process of deciding which of those available biosimilars a patient gets if they’re a new patient, or is switched to if they’re an older patient, rests with the prescribing clinician

“Hospital trusts [or the relevant commissioners] will then purchase from the individual manufacturer using the terms in that framework agreement,” says Smith.

“If a biosimilar has been selected through the tender or procurement process by the CMU, it’ll be available, but trusts or commissioners will decide which biosimilars they will use and it’s up to them to develop the formulary.

“The process of deciding which of those available biosimilars a patient gets if they’re a new patient, or is switched to if they’re an older patient, rests with the prescribing clinician.”

In the case of adalimumab, the commissioning arrangements depend on the indication it is being used for.

“For conditions such as psoriasis, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and Crohn’s disease, it’s clinical commissioning group (CCG) [commissioned]; for other conditions, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, it’s specialist commissioned,” explains Caron Underhill, a rheumatology pharmacist with responsibility for biologic therapies at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

This means that, in England, around 94% of commissioning of adalimumab will be carried out by CCGs and the remainder will be through specialised commissioning, which helps people with rare and complex conditions and supports pioneering clinical practice in the NHS.

These commissioning arrangements, and the fact that patients on adalimumab are reviewed every six months, make the switch and take-up slightly more complex, says Smith.

“But one of the things we are seeing, having gone through switches with other biosimilars, [is that] the NHS is preparing itself for this,” he adds.

In Wales, adalimumab will be incorporated into the national prescribing indicator, which is used to highlight therapeutic priorities for Wales and compare the ways in which different prescribers use particular medicines. It will also be added to the NHS Delivery Framework measure, which measures the NHS’s sevice delivery to show how it is influencing the health and wellbeing of Welsh citizens.

“Health boards are currently developing plans to realise efficiencies resulting from prompt and comprehensive adoption of biosimilar adalimumab. These will be supported by a national procurement exercise led by the All-Wales Drug Contracting Committee later [in 2018],” says Andrew Evans, chief pharmaceutical officer for Wales.

Healthcare Improvement Scotland published a prescribing framework for biosimilars in March 2018[4]

.

“The introduction of adalimumab in Scotland will be based on previous experience with infliximab and etanercept, which successfully achieved very high uptake through a number of mechanisms, including sharing best practice, engagement with clinicians, nomination of NHS Board biological leads, procurement and regular comparative updates on board-by-board uptake,” according to a spokesperson for the Scottish government.

“The approach for adalimumab will be an extension of this and NHS boards, through their clinicians, have already started the conversations with patients.”

Initiating the switch

Underhill helped set up the biologic service in her hospital and is now responsible for implementing the adalimumab switch programme, alongside a team of specialist nurses and administrative support.

“With clinician agreement, we’ve agreed across the specialities — rheumatology, dermatology, gastroenterology — that we’re going to go ahead, so it’s up to me to implement the process and get the ball rolling,” she explains.

Her team is already speaking to patients as they come into the clinic for their routine appointments to tell them about the possibility of a biosimilar switch towards the end of the year.

Source: Courtesy of Caron Underhill

Caron Underhill, a rheumatology pharmacist with responsibility for biologic therapies at University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, says it is crucial that healthcare professionals have face-to-face discussions with patients about the possibility of a biosimilar switch

“You can’t just spring it on patients,” she says. “We have to tell them in person — we can’t just send them a letter in the post — [it’s important for them to have] a face-to-face discussion with people they know.”

You can’t just spring it on patients, we have to tell them in person — we can’t just send them a letter in the post

As part of educating patients, Underhill and her team have designed a patient information leaflet, which, she says, has now been adopted by NHS England. However, she explains that, at the moment, this is all the team can do because it is not possible to predict exactly which product patients will be switched to, if any.

“If in December [2018] it looks like we are switching, then we will contact patients again — they’ve already been forewarned,” she says.

When it comes to choosing the most appropriate biosimilar, Underhill explains that several factors, in addition to price, will be taken into account. These factors include volume, the device and citrate content — citrate content in Humira initially caused stinging in patients when injected but was later reformulated.

“Patients wouldn’t go back to the stinging even though they’d put up with it for years,” she says.

The chosen drug will be added to the local formulary and then, provided the patient fulfils the criteria set out by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the therapy will be offered.

Reassuring patients

One of the challenges associated with a biosimilar switch programme is appropriately addressing patients’ concerns. Clare Jacklin, director of external affairs at the National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS), says that the majority of biologic units resort to a blanket letter, varying in quality and accuracy, to all patients being switched.

“Some appalling letters are going out, as well as others that are very informative and well crafted,” she says.

Source: Courtesy of Michele Le Tissier

According to Clare Jacklin, director of external affairs at the National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society, there are four main concerns that patients have about switching to a biosimilar — the first of which is whether they have a choice about it

“[The] NRAS has had input into some department letters and this has improved them by making them easier to understand, as well as [including] good and clear signposting [also available via the NRAS patient helpline] to where to get more information on biosimilars.”

She explains that there are four main concerns that patients have about switching — the first of which is whether they have a choice about it.

Many are being told they are switching rather than being asked, and those that are being asked often are not really getting good information about what it means so can they truly give consent?

“Many are being told they are switching rather than being asked, and those that are being asked often are not really getting good information about what it means, so can they truly give consent,” says Jacklin.

The second concern, she adds, is whether they can switch back to the originator if the biosimilar is not as effective at controlling their disease.

“While it would appear they have the right to switch back, there may be delays in getting agreement from the ‘payers’ for this to happen and some patients are then off medication for some time, which can cause flares,” she says.

Thirdly, some patients are told that if they agree to switch, more people will have access to the treatment, says Jacklin, which means that patients can become concerned that by not switching, they are potentially blocking other patients from receiving treatment.

“The [final] concern is over the administration of the biosimilar — [this might be a] new device to get used to, or a new home care delivery process to familiarise themselves with,” adds Jacklin.

Smith agrees and says that with adalimumab there is a significant home care element that should be taken into account when assessing the best-value product.

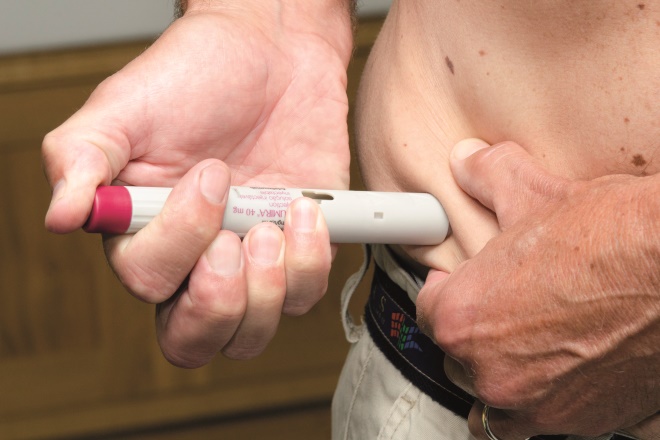

Humira is administered every other week via subcutaneous injection with a special pre-filled syringe. The manufacturers provide an auto-injector that conceals a needle that is released when you press a button. Syringes are delivered to the patient’s home by a home healthcare delivery company, together with a sharps bin for used syringes and alcohol swabs for cleaning the skin.

Source: Dr P Marazzi / Science Photo Library

Humira is administered every other week via subcutaneous injection with a special prefilled syringe. The manufacturers provide an auto-injector that conceals a needle which is released when the patient presses a button

According to the NRAS, most people can learn how to do subcutaneous injections themselves, although they are sometimes done by a healthcare professional or a family member[5]

.

One of the things that’s been really important and powerful in increasing the use of biosimilars in the UK has been education of both clinicians and patients

Smith says that, for patients, the underlying issue is “fear of the unknown”.

“The word ‘biosimilar’ itself can cause concern among patients — ‘what if it’s only similar’?

“One of the things that’s been really important and powerful in increasing the use of biosimilars in the UK has been education of both clinicians and patients.”

Smith stresses the importance of explaining the regulatory process — the fact that the quality, safety and efficacy have to be shown to not be meaningfully different from the originator — and consulting with patients so that they are properly informed and have the opportunity to ask questions.

“People want good-quality information with very clear details of what to do if they don’t want to switch or, having switched, have any issues,” says Jacklin.

“It is important to utilise the support of patient organisations, such as the NRAS, to give the impartial and lay perspective on biosimilars. The peer support that we offer can make a huge difference.

“If someone is concerned about going on to a new drug, biosimilar or otherwise, and they can be put in touch with someone else who has been on that particular medication, it can reduce those anxieties and concerns,” she says.

Smith adds that, where patient engagement has been done well, there are very few patients who either resist the switch or ask to go back.

“We’re talking single figures of percentage,” he says.

Having enforced blanket switching is eroding clinical decision making, as well as the confidence and trust the individual patient has in their consultant to make the right decision for them

Jacklin agrees that switchback rates reflect how well the switch is handled and communicated. However, she adds that the decision to switch must be based on clinical reasons and not purely on financial savings.

“Having enforced blanket switching is eroding clinical decision making, as well as the confidence and trust the individual patient has in their consultant to make the right decision for them,” she says.

“The most frequent reasons we have heard of for switching back to originator are reduced efficacy or perceived reduced efficacy [and] difficulty in administering the biosimilar due to change in device and side effects. A small number of patients have allergic reactions to the biosimilar, mostly infliximab.”

However, Underhill says that at Southampton they have had no issues with patients being concerned about switching to biosimilars.

“We monitor patients regularly, pick up any concerns and [practice] pharmacovigilance. We’ve got to have confidence in the European Medicines Agency that it’s done all the rigorous biological checks and that it’s been thoroughly tested.”

Regulations and incentives

EU legislation mandates that all medicines with a new active substance, and all biological medicines approved after 1 January 2011, are subject to additional monitoring for safety[6]

.

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency requests that those reporting a suspected adverse drug reaction (ADR) to a biologic must provide the brand name and specific batch number on any ADR report to ensure that any safety concerns are attributed to the correct product, manufacturer and batch, and the root cause of the issue can be accurately determined.

NHS England has developed a Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) incentive to support the faster uptake of best-value medicines in specialised commissioning, with a particular focus on best-value generics and biologic medicines, including biosimilars.

The 2017/2019 CQUIN payment trigger relates to hospital trusts being able to demonstrate adoption of best-value biologics, including biosimilars, in 90% of new patients within one quarter of guidance being made available and in 80% of applicable existing patients within one year[1]

.

While this appears ambitious, Underhill says that in the case of infliximab, nearly all of her patients were switched over in just eight weeks. “The patients come into the infusion unit every eight weeks, so we changed them over as their prescription was renewed — you can’t just change everyone’s prescription overnight as the workload would be huge.”

Learning from past switches

Underhill says that her experience of switching to other biosimilars has taught her the importance of effective coordination between patients, doctors, nurses and pharmacists.

“[This] is key to ensuring successful switching, and switching in a way that maintains patient confidence,” she says.

So is switching to the best-value biologic worth it in the long run? Underhill says that, although switch programmes are a lot of work, the savings are significant and the money saved can be reinvested back into the trust and into the service to enhance patient benefits.

“If you look at infliximab, we saved £100,000 a month. Adalimumab is millions of pounds a month across the country, every month we delay, it’s millions.”

Smith agrees that the numbers say it all.

“It’s not just pounds saved — these pounds can be diverted to other treatments,” he explains, adding that some savings made through switching have helped to pay for more specialist nurses in some hospitals.

“It’s about increasing patient access to medicines, and it’s about better treatment of patients — the overall care package can be enhanced.”

| Table 1: Estimated patent and exclusivity expiry dates for best-selling biologics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Source: Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal[7] | ||

| Biologic | Approval date (EU) | Estimated patent expiry date (EU) |

| Adalimumab (Humira; Abbvie) | September 2003 | October 2018 |

| Insulin detemir (Levemir; Novo Nordisk) | June 2004 | November 2018 |

| Teriparatide (Forteo/Forsteo; Eli Lilly) | June 2003 | August 2019 |

| Catumaxomab (Removab; Neovii) | April 2009 | May 2020 |

| Eculizumab (Soliris; Alexion) | June 2007 | May 2020 |

| Trastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla; Genentech) | November 2013 | June 2020 |

| Belimumab (Benlysta; GSK) | July 2011 | January 2021 |

| Ipilimumab (Yervoy; Bristol-Myers Squibb) | July 2011 | December 2021 |

| Belatacept (Nulojix; Bristol-Myers Squibb) | June 2011 | June 2021 |

| Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada; Sanofi) | September 2003 | May 2021 |

| Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia; UCB) | October 2009 | July 2021 |

| Ranibizumab (Lucentis; Genentech) | January 2007 | January 2022 |

| Bevacizumab (Avastin; Genentech) | January 2005 | January 2022 |

| Denosumab (Prolia/Xgeva; Amgen) | May 2010 | June 2022 |

| Liraglutide (Saxenda/Victoza; Novo Nordisk) | June 2009 | August 2022 |

| Pertuzumab (Perjeta; Genentech) | March 2013 | March 2023 |

| Ramucirumab (Cyramza; Eli Lilly and co.) | December 2014 | May 2023 |

| Brentuximab (Adcetris; Takeda) | October 2012 | August 2023 |

References

[1] NHS England, NHS Improvement & NHS Clinical Commissioners. Commissioning framework for biological medicines (including biosimilar medicines). 2017. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/biosimilar-medicines-commissioning-framework.pdf (accessed August 2018)

[2] Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry & UK BioIndustry Association. Biological and biosimilar medicines in the UK. 2014. Available at: http://www.abpi.org.uk/media/1391/biological_biosimilar_medicine_uk.pdf (accessed August 2018)

[3] NHS England. Regional Medicines Optimisation Committee briefing best value biologicals: adalimumab update 3. 2018. Available at: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Adalimumab-RMOC-Briefing-Final-July.pdf (accessed August 2018)

[4] Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Biosimilar medicines: a national prescribing framework. 2018. Available at: http://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/idoc.ashx?docid=93faeca2-1f4d-4ffc-a41f-7a17909ae236&version=-1 (accessed August 2018)

[5] National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society. Biologics: the story so far. 2013. Available at: https://www.nras.org.uk/data/files/Publications/Biologics-.pdf (accessed August 2018)

[6] European Medicines Agency. Biosimilar medicines. 2018. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/general/general_content_001832.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580bb8fda (accessed August 2018)

[7] GaBI journal editor. Patent expiry dates for biologicals: 2017 update. Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Journal 2018;7(1):29-34. doi: 10.5639/gabij.2018.0701.007