Shutterstock.com

While reading the morning news on your smartphone, a job alert from professional networking site LinkedIn pops up on your screen. Another notification from Facebook tells you a colleague has commented on a post on a work-related page and you reply. You then check your email, and notice a Google alert telling you that an original research paper has been published on a subject you searched for the other day — all in the palm of your hand in a matter of moments. As a member of a professional association, the services you require are evolving and the challenge for your membership body, and many like it, is to adapt.

Professional associations in healthcare and science have traditionally played an instrumental role in providing advocacy, information, networking opportunities and professional advice. Yet technology and social changes are having an unprecedented impact on these roles.

Since 2008, US-based consultant Seth Kahan has been running workshops for leaders of professional associations, helping them to grapple with issues such as staying relevant and to work out how to revitalise their membership bodies. “I am helping them to reinvent themselves for the 21st century,” he says.

Courtesy of Seth Kahan

Consultant Seth Kahan says that the trust people have in professional associations is an asset that associations should exploit

There are now associations that represent almost every discipline or profession, from innkeepers to doctors, with approximately 400 professional bodies in the UK alone. Some associations are part financed by large publishing businesses, such as the American Chemical Society, with revenue of US$500m. Most associations are funded by a mix of incomes, including membership fees. But can these associations still rely on a buoyant membership continuing to pay their dues? A recent report ‘Membership matters’, from scientific, technical and medical publisher John Wiley, suggests maybe they can’t[1]

.

In 2014, Wiley carried out a survey of almost 14,000 researchers and professionals from 75 disciplines. It divided respondents into generations, the main ones being baby boomers (born between 1945 and 1965); generation Xers (born 1965–1980); and millennials (born 1980–2000). Roughly three quarters of those surveyed were members of a professional body or association, but less than half of millennials were members (48%), compared with 73% of generation Xers and 83% of baby boomers. The main barrier to membership was cost, but younger members also displayed a general lack of interest. Half of millennial non-members said they were not members because they had never been invited to join. The appeal of membership benefits decreased across the generations.

| Top reasons for joining based on mean ranking (lower number = higher rank) | Silent generation (1900-1945) | Baby boomers (1945-1965) | Generation X (1965-1980) | Millennials (1980-2000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| – = reason not included in top five ranking Source: Wiley membership survey 2014 | ||||

| Quality of research-based content | 1.77 | 1.86 | 2.00 | 2.05 |

| Prestige of organisation | 1.98 | 2.11 | 2.33 | 2.57 |

| Required certification for career | 2.04 | 1.97 | 2.36 | – |

| Required to attend conference/annual meeting | – | 2.23 | 2.37 | 2.55 |

| Networking opportunities | 2.09 | 2.28 | 2.39 | 2.60 |

| Value of membership benefits to me | – | – | – | 2.83 |

| Other | 2.17 | – | – | – |

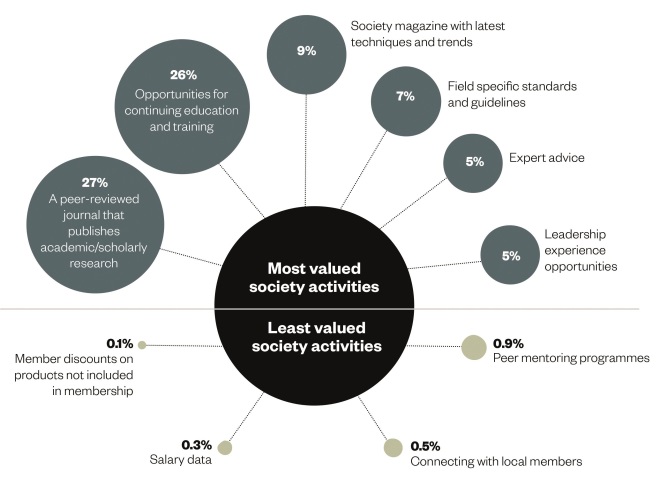

Figure 1: Most and least valued society activities by members and non-members

Source: Wiley membership survey 2014

A peer-reviewed journal is the society activity that survey respondents found the most appealing, closely following by opportunities for continuing education and training. Member discounts and salary data were the least appealing activities.

Not all societies report a drop in membership though. For example, Helen Pain, deputy chief executive of the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), says: “Overall, we have a 90% retention rate, upwards of 95% for our professionally qualified category.”

Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) chief executive Helen Gordon says the RPS has enjoyed retention rates in the mid-90%, “which actually beats the benchmark of most professional associations, and what is really buoyant is our younger membership”. RPS membership rose by 5.4% in 2015, but this follows a large drop from pre-2010 levels, when the RPS shed its regulatory function[2]

. The proportion of GB-registered pharmacists who have chosen to pay for voluntary membership of the RPS is 55%[2]

.

Millennials are not going to carry on being part of a member organisations because that’s what they have always done

“[Millennials] are not going to carry on being part of a member organisations because that’s what they have always done,” says Simon Edwards, director of communications at the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) of England. “They will change their membership more readily than people have done in other generations.” The RCS has established a membership engagement office to find out what members really want. The RPS is also paying attention: “We have now got a younger group of pharmacists that we are listening to, they have met and advised us on a number of issues so that we can tailor our offering,” says Gordon. She explains that the RPS runs specific events for younger members to inform them of educational developments and has a constant dialogue with the British Pharmaceutical Students’ Association, although she adds that “there is always more that we could do”.

Part of the problem in engaging younger members is the age of the associations themselves, says Illinois-based associations consultant Mary Byers. “Many of [the associations] are governed by by-laws, policies and rules that were created decades ago and, though that makes for some nice history, culture and tradition, it doesn’t necessarily meet with today’s expectations,” she says. Byers suggests that associations should think about creating new models of leadership that may appeal more to millennials. She calls it “micro-volunteering” — allowing members to take on short assignments that do not require long-term commitments but still allow them to get involved.

These days you can get anything you want for free through the internet. So the value, which was basically transactional, has been usurped by technology

Another barrier to engaging millennials is that the “value proposition” of associations has been disrupted by technology, says Kahan. “The reasons why people joined [professional associations] in the past were to associate with people like themselves, to get the latest education,” he explains. “These days you can get anything you want for free through the internet. So the value, which was basically transactional, has been usurped by technology.”

Online professional networking

Professional and scientific networking online has become big business. Several major players have created large online networks, including Researchgate.net, which claims to have 9 million users, and Academia.edu, which claims to have 34 million users. The sites vary, but they broadly allow users to connect and share publications. A plethora of networking and discussion sites are also available to professionals. Public sites, such as LinkedIn and Facebook, allow anyone to form professional groups, and specific sites, such as the US-based PharmQD, provide news, networking and access to job listings and educational programmes. However, Edwards points out that not all professions are comfortable with the approach. “We don’t really see online discussion forums taking off in the [medical] field at the moment,” he says, although he admits that may change.

Research network Mendeley, launched in 2008 by three German PhD students, may be smaller than its competitors, but its £65m purchase by academic publishing giant Elsevier in 2013 could make it the most significant. Co-founder Jan Reichelt says the platform has around 5 million users, with biology and medical scientists most strongly represented. It enables interdisciplinary networking opportunities and, now with links to a major publisher, integration of a wider set of academic activities. For example, Elsevier has created a new open access online journal Heliyon. “You have a one-click submission button in Mendeley,” says Reichelt. Elsevier is also looking at using Mendeley for online peer review.

Societies help to build your real life network, which complements your online network

But Reichelt doesn’t see this as competition for the activities of professional societies. “There might be some overlap but actually I think they augment each other,” he says. “Societies help to build your real life network, which complements your online network.”

The symbiotic relationship between academic publishers and learned societies can also be seen in the other services that publishers are starting to offer their society partners. Bill Deluise, vice president for society strategy and marketing at Wiley, explains that the publisher now offers digital job advertisements and career development resources that drive both member engagement and a financial return for the society via advertising. It also provides marketing services, including emails, newsletters and social media engagement. But Deluise does not consider these new directions as competition: “Scientific and scholarly societies are among the most important partners we have,” he says. Wiley provides professional expertise and the societies bring unmatched discipline knowledge and their deep networks. “We are more effective together,” he explains.

Education and development

It is not just technology that has disrupted the value proposition of associations, changes to education and development have also affected their role in the past few decades. Once the major providers of continuing professional development (CPD), associations now compete with commercial organisations and universities. Edwards says this has certainly been the case in medicine. “Training used to be much more integrated with the RCS but it’s less so now.”

The University of Manchester’s Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education (CPPE) is funded by the Department of Health to provide educational materials for pharmacists in England. Its director Christopher Cutts says that organisations such as the CPPE have increased their provision of CPD ten-fold over the past decade. “We have also seen an increase in providers over the past ten years or so,” says Cutts, explaining that large employers offering in-house training are now major providers. The role for professional associations, Cutts suggests, is in developing policies that set out the nature and type of continuing education necessary to meet patients’ needs.

The RPS still provides valuable educational resources, according to Helen Gordon: “Particularly for young pharmacists, the Foundation [Programme] has proved to be incredibly popular and helpful. Giving people who have just started in their career a framework to help them is really important.” The RPS professional development programme has been designed for members who are in their first 1,000 days of practice or returning to work after a career break.

Source: Simon Wright / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Helen Gordon, chief executive of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, says that, unlike niche groups, professional bodies are able to provide much broader leadership

Strength in reputation

Although it appears that learned and professional societies are being squeezed out of their traditional roles, Kahan believes that the trust people have in them is a major asset that should be exploited. “Trust is actually one of the key assets in the new market economy — it’s very difficult to get, but organisations like Amazon have successfully acquired it, which is one of the things that makes them so strong.” In the same way as commercial brands, many professional associations already have trust; people see them as authoritative voices that can be believed and respected. They now have to use this asset to help them thrive, says Kahan.

Trust is actually one of the key assets in the new market economy

Associations should use their reputations as trustworthy organisations to widen their relevance, rather than focusing on a narrow professional audience, Kahan suggests. “Take responsibility for being the resource around the world in your space,” he advises. Associations should become campaigning organisations, allowing members and the public to see them make a constructive contribution to a societal problem. The American Nurses Association (ANA), for example, is running a campaign in autumn 2016 called ‘Healthy nurse, healthy nation’, which aims to increase the “personal wellness” of 3.4 million nurses in the United States and, by extension, the country (healthy nurses make more credible role models and educators). The ANA benefits from more engaged members, new partners and a higher profile, says Kahan.

Widening eligible membership may also be an answer. “Societies that remain insular are effectively applying a tourniquet between themselves and the global economy, and that will result in their rapid decline,” Kahan believes. While not all societies will want to dilute their professional status, actively seeking members from other disciplines or from the general public is a strategy that some associations are considering. Debi Sutton, director of membership and marketing at the Entomological Society of America, says a recent member survey showed that only 33% of members classified themselves as entomologists. “Another 13% selected ecologist, and 8% general researcher. So we’ll be looking at these other areas to see if there are ways to grow membership and customer engagement,’’ she says.

Advocacy and influence

For some organisations, particularly professional associations, membership requires some form of qualification. Wiley’s ‘Membership matters’ report found that the prestige of an organisation and the status that confers is a strong motivation for joining[1]

. “Professional recognition, we know through surveying our members, is widely held in high regard, so the use of designatory letters, the ability to be effectively peer reviewed in order to gain membership, is what has really helped us to retain members,” says Pain.

Professional recognition… is widely held in high regard, so the use of designatory letters, the ability to be effectively peer reviewed in order to gain membership, is what has really helped us to retain members

Edwards believes surgeons join the RCS for “the prestige of being a member of their professional body”, but stay members “for the voice and the influence of the college”.

“We have a large role in influencing government and taking the voice of the profession forward,” he adds. Pain agrees that the role that professional bodies play in advocacy is their main strength. “About ten years ago our members asked us to have a stronger voice in representing chemistry and that’s what we seek to do. It’s been both responsive, but also proactive in a thought leadership capacity.”

Another body that emphasises its advocacy role is the Canadian Pharmacists Association (CPhA). In 2014, the association went through a radical reshaping to become a federal body representing the ten Canadian provincial societies, rather than competing for individual members. Chief executive Perry Eisenschmid says the new model provides “a much stronger national voice” and “better coordination of advocacy for the profession”. In the past two years, the association has expanded its policy team to eight expert staff and “developed a national strategy, which focuses on the key priorities”, adds Eisenschmid.

Courtesy of Perry Eisenschmid

Perry Eisenschmid, chief executive of the Canadian Pharmacists Association, says the association underwent a radical reshaping in 2014 and has increased its advocacy role

The CPhA’s reorganisation came at a time of change in Canada, with the 2015 election of prime minister Justin Trudeau, so it was able to contribute its views to legislative debates, such as new laws on euthanasia. “That agenda has typically been informed by physicians in Canada,” says Eisenschmid. “We made sure that pharmacists’ perspective was brought to the table.” The CPhA also carried out research into the potential role of pharmacists in the medical distribution of cannabis.

Although many potential members acknowledge strong representation is important to them, the question is whether their particular professional body is doing a good job in this area. Over the years other organisations and campaigning groups have provided advocacy for professionals and academics who felt the need for stronger representation. For example, the Campaign for Science and Engineering was set up in the UK in the 1980s to campaign for more investment in science. In pharmacy, the Pharmacists’ Defence Association, with 22,000 members, was set up in 2003 to represent individual community pharmacists because, it says, historically other organisations did not serve community pharmacists’ interests.

What sets us apart is that we are the only place that is representative [of] and representing the entirety of the pharmacy profession

But Gordon says, unlike niche groups, professional bodies are able to provide much broader leadership: “What sets us apart is that we are the only place that is representative [of] and representing the entirety of the pharmacy profession.” She adds that by using the voice of the membership, the RPS is able to be “the face of the pharmaceutical profession” and “provide a leadership role to shape the profession going forward, with policy work at governmental and NHS levels”.

Kahan believes that societies also have a huge task in managing professions in difficult times. He says we are in a period of “exponential overlapping change” that is not going to slow down, so “every profession is living in a world of uncertainty”.

“Societies have to take some responsibility for helping members to make sense of that uncertainty and to identify the emerging trends that are most likely to impact them,” he adds.

While many professional associations have survived for almost two centuries, they may now be facing their greatest challenge yet — staying relevant in a competitive digital age, where information is at everyone’s fingertips and we can immediately communicate with almost anyone, anywhere. Professional associations must think about how their particular combination of guidance, knowledge and trusted advocacy can serve their members and the public in a way that no one else can.

References

[1] Wiley. Membership matters: lessons from members and non-members [online]. Oxford: Wiley; 2015. Available at: http://news.wiley.com/exchanges-survey-whitepaper (accessed 6 October 2016).

[2] Robinson J. RPS annual review reports 5.4% rise in core membership. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2016; 296:312. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2016.20201128