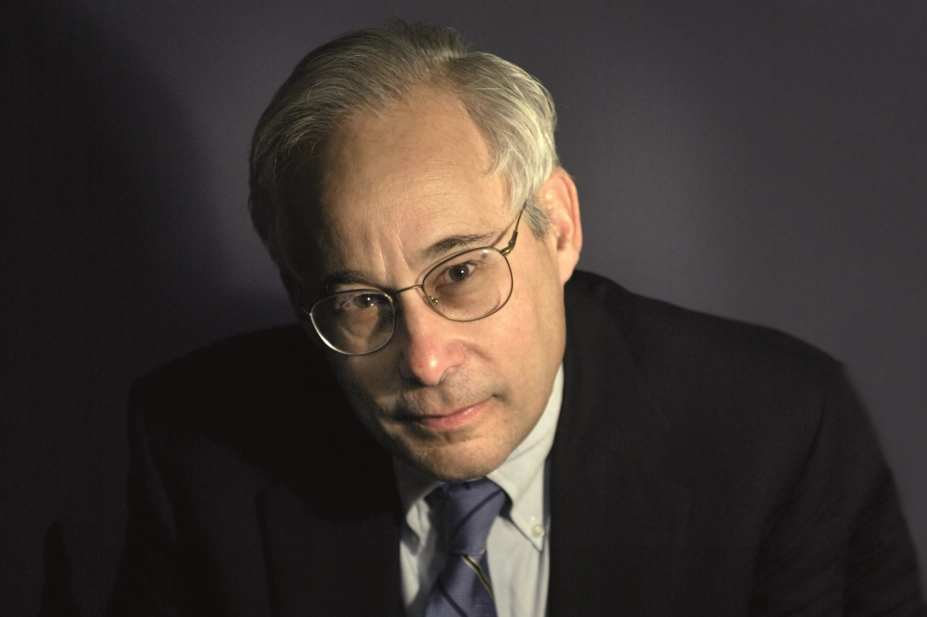

Courtesy of Donald M. Berwick

Donald M Berwick is president emeritus and senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement — non-profit organisation focused on motivating and building the will for change, partnering with patients and healthcare professionals to test new models of care — and a former administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. He originally trained as a paediatrician, but has subsequently become a leading authority on healthcare quality and patient safety. Following the publication of the Francis Report (by Robert Francis QC), which examined the breakdown of care at Mid Staffordshire Hospitals, Berwick chaired a review by the National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England. Their findings and recommendations were published in 2013 in “A promise to learn — a commitment to act: improving the safety of patients in England”.

What progress do you think the NHS has made in improving patient safety since your review was published?

There has definitely been progress, and the vanguard sites for the New Models of Care Programme, focused on care transfer, will have good effects on safety. I’m impressed with the work of the vanguard care home sites, which will have implications for safety. In addition, the Academic Health Science Networks are sound efforts to build collaborative work on areas of safety.

What we said in the review about the need for a culture of learning and strong leadership has been taken seriously, although learning needs to be systemic — right across an organisation. Strong leaders are important to ensure that organisations are continually reminded of the importance of investing in safety and education. But enormous cost pressures continue to be a dominant theme in the NHS and divert attention. It’s important that safer care remains a priority.

At a global level, the Department of Health in England has taken the lead in re-energising the ongoing work of the World Health Organization on patient safety. The UK hosted the first Patient Safety Global Action Summit for ministers in March 2016, and there will be a further conference in Germany in 2017.

With so much pressure to reduce costs and achieve targets in the NHS, is there a risk that safety will get sidelined?

In a misguided effort to reduce costs, more pressure may be put on the workforce, with less time for learning and reflection and a negative impact on safety. But I firmly believe that quality improvement is an important route to reducing costs, and safety is an important part of that. We need to keep making that point because it’s not immediately obvious that, if we put our pounds into improving safety, we can make savings overall.

I get impatient with the media always focusing on the bad things

Organisations need to work closely with accounting functions to notice how investment in safety can improve the cost profile. Finance people are just as wise and open minded as anyone else, and many are interested in digging deeply into the relationship between quality and cost, but there is a need to improve understanding about how safer, high-quality care can reduce costs.

In the vanguards working on integration of care, it’s a virtual certainty that better coordinated care will lead to lower costs, and it also happens to make care safer. Many are doing remarkable work to make care smoother and achieve better results for patients, with lower lengths of stay and overall reductions in total costs of care.

I get impatient with the media always focusing on the bad things, because we are seeing good things happening. At the moment, they’re happening in pockets, and the challenge for the NHS will be to see that these models become available to everyone.

Pharmacy dispensing is safe compared with other areas of healthcare, but overuse and handovers are key areas where they can take the lead

In terms of medicines safety, what should be the main priorities for pharmacists and other healthcare professionals to reduce accidents, errors and misuse?

Better handovers, coordination and simplification, especially for older people, would be top of my list. Pharmacists have a big role to play in ensuring that patients get the right medicines, particularly when they are moving from one part of the system to another – from hospital to home or from long-term care to acute care. Unless there are good systems in place to track medicines across boundaries, patients can end up in messy and harmful patterns of medicines use.

Pharmacy dispensing is safe compared with other areas of healthcare, but overuse and handovers are key areas where they can take the lead.

In your presentation at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society conference on medicines safety (3 November 2016), you talked about the trend away from hospital towards community care of patients. What are the main challenges for ensuring patient safety as care moves to the community, particularly in relation to medicines?

There is a good trend away from patients and families being dependent on institutional care towards embedding care in the home. Self-care has great potential in making care much more responsive to real needs and reducing costs. As care moves to the community, I would expect it to get safer. But that requires giving patients ready access to information and a lot of that can happen through internet-based care.

I hope and believe the NHS will be advancing telemedicine-based care and that will mean safer care

Telemedicine is a wonderful area for the future, and the day is not far away when we will be projecting knowledge about illness, care and medicines into people’s homes. I hope and believe the NHS will be advancing telemedicine-based care and that will mean safer care.

I see no reason why doctors and nurses can’t be in much easier and more frequent contact with their patients than they currently are in their offices. In some ways, the reliance on visits to offer care is a dinosaur — adding cost and wasting patients’ time when they just want to ask a question. There is enormous scope for both synchronous and asynchronous support, including between patients with the same condition, and providing a trustworthy internet-based reservoir of information could remove the need for consultations altogether in many cases.

Text messaging support also has great potential because people of lower income use it more than those with higher incomes, so it can be especially useful for care in vulnerable groups.

In the United States, Kaiser Permanente [an integrated managed care consortium, based in Oakland, California] provides care for nearly 11 million patients and 52% of its encounters are now virtual. It’s all starting to happen, but it can happen a lot more.

How does our healthcare system compare with other countries in terms of safety? Is patient safety an issue in the United States?

I think we’re on parallel tracks. Both countries have shown serious commitment to improvement and, because you have a national health service, your government’s leadership on safety has been more significant. When I was administrator of our Medicare and Medicaid systems from 2010 to 2011, we launched a national programme, called Partnership for Patients. It was a US $1bn investment in patient safety, and it has had a big impact on reducing patient injuries in hospitals. The core of its success was learning networks that enabled hospitals to work together on common goals, such as reducing pressure ulcers, infection and surgical errors, and the collective learning experience was key.

In the UK, you have some world leaders in patient safety, for example, Dame Sally Davies [chief medical officer for England], who has become a vital figure in promoting efforts to prevent medication-resistant infection, a big part of which is better use of antibiotics. Sir Liam Donaldson [past chief medical officer for England] is another person of international stature who has focused world attention on patient safety for more than two decades. Hundreds of countries now have patient safety projects that probably wouldn’t be there without him.

My one regret is that I no longer see patients

You started your working life in paediatrics. What took you into healthcare policy and was it the right decision?

When I was at Harvard, the medical school had a joint programme with the John F Kennedy School of Government, so it was possible to get a Masters in Public Policy as well as a medical degree. That was probably the most important influence because I found it interesting to think about the regulatory, statutory and management environment when I was seeing patients and how this was allowing me to do my work properly — or not. I soon came to see that unless we work on systems of care as a whole, even very dedicated clinicians are impeded in getting their work done. My one regret is that I no longer see patients. I became so busy in the world of policy, management and improvement that I couldn’t keep up the ongoing study and practice that would have allowed me to continue to see patients, and I miss that every day.

You have a multitude of roles in the US, the UK and elsewhere. How do you have time for them all, and which give you most pleasure?

They energise and inspire me, and I always do better when I’m watching and learning from people, so I can carry lessons elsewhere. It’s demanding but satisfying. What gives me most pleasure is when I’m visiting a doctor, hospital ward or healthcare facility, because it’s where the meaning is. It reminds me about real people who are trying to have safe and successful lives. We can write all the rules we want and do all the measuring we want, but none of it matters until one person has their suffering relieved, their safety enhanced or their talents maximised.

What impact do you expect the Trump presidency to have on US healthcare, and what would be your advice to him?

No one knows yet. I’m worried because in some of his rhetoric and his early appointments, president Trump is showing a concerning willingness to do things that might lead to less accessible care, especially for people of low income. He also seems to be planning to decrease our nation’s investment in supporting the redesign of care – which is badly needed — and to place a greater burden on individuals who are most vulnerable. Hopefully it won’t happen but, right now, we have to be on alert.

My advice to president Trump would be to ensure that healthcare is a human right in America — and mean it

From time to time, Trump has said he doesn’t want to take away aspects of Obamacare that are dear to people’s hearts, such as ‘guaranteed issue’, which means care for people with pre-existing illnesses. However, as we see the policy ideas that are coming forward, it’s hard to see how they can accomplish the decreases in support for healthcare coverage on the one hand and still insist on guaranteed issue so, potentially, many millions of people could lose insurance coverage.

My advice to him would be to ensure that healthcare is a human right in America — and mean it — and invest public and private resources for continuing improvement in care, including development of integrated care at the core of our health system.

References