Pharmaceutical Journal

“Second day off Effexor [sic] & on Viibryd here. Brain zaps are fun. And by fun, I mean horrendous & miserable,” a woman named Rachel tweets about her antidepressants. Although this kind of post on social media does not resemble a traditional adverse drug reaction (ADR) report, pharmacovigilance experts are investigating whether this type of public information on Twitter, Facebook and on patient forums or blogs, might help regulators and pharmaceutical companies monitor the safety profile of medicines. Rachel’s tweet, for example, might form a report of paraesthesia, a withdrawal symptom of Efexor.

Up to 90% of side effects to drugs are not reported, according to some estimates. “Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are grossly under reported by everyone, including healthcare professionals, but particularly so by patients,” says David Lewis, head of global safety at Novartis, who is co-ordinating the involvement of pharmaceutical companies in a €2.3m three-year public-private project called Web-RADR (Recognising Adverse Drug Reactions).

Mining data from social media gives us a greater chance of capturing ADRs that a patient wouldn’t necessarily complain about to their doctor or nurse

Data from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) indicate that patients are not reporting side effects adequately through official channels and several regulators are exploring the possibility of making use of the abundant information swirling around social networks.

“Mining data from social media gives us a greater chance of capturing ADRs that a patient wouldn’t necessarily complain about to their doctor or nurse. Physicians are great at diagnosing illnesses and noting objective signs, but patients are great at reporting subjective reactions and feelings,” says Lewis. “For example, a psychiatrist can’t see suicidal ideation as an ADR while a patient can describe it perfectly.”

Trawling social media for drug safety information or even, potentially, drug efficacy data, however, throws up important questions about the legal and ethical responsibilities of companies and regulators alike, such as who should use these data and what approach can be taken with patients who post online. That’s besides overcoming the technical challenges in turning large volumes of unstructured and often low-quality data into useful information.

First sight

François Houÿez, director of treatment information and access at patient group Eurordis, says if the regulator contacts the person making the post, then we may see a negative reaction from the user, who may not appreciate that sort of surveillance

In 1997, a man living with HIV in the United States started to report the strange shape of his abdomen after taking a new antiviral. “My belly button went from an inny to an outy,” he said. His words were not written in a personal diary, but on a patient internet forum. This is an early example of a patient making a report about a drug side effect using social media, says François Houÿez, director of treatment information and access at Eurordis, a group involved in Web-RADR that represents patients with rare diseases.

Soon, other patients in the United States and Europe taking the same drug, indinavir (Crixivan), published similar posts on the Crix Belly forum, a prototype discussion board.

The side effect reported on “Crix Belly” became known as lipodystrophy syndrome, which is associated with taking antiretrovirals to treat HIV infection. The problem had not been spotted earlier because clinical trials ran for 48 weeks, and the syndrome does not develop until after 48 weeks of therapy.

“Because of the patient reports, drug regulators in Europe and the United States alerted prescribers of the risks,” says Houÿez.

Noise filter

There are indications that social media can be used to find leads to possible adverse reactions, but it is still early days in realising it as a proven method. Epidemico, a small US company, a subsidiary of Booz Allen Hamilton, is developing algorithms to pick up side effects from social media as part of the Web-RADR project. It is also working on a similar two-year pilot study with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which is one year in.

Epidemico uses its Med-WatcherSocial platform [demonstration website] to look for possible ADRs from social media posts for some 1,400 drugs.

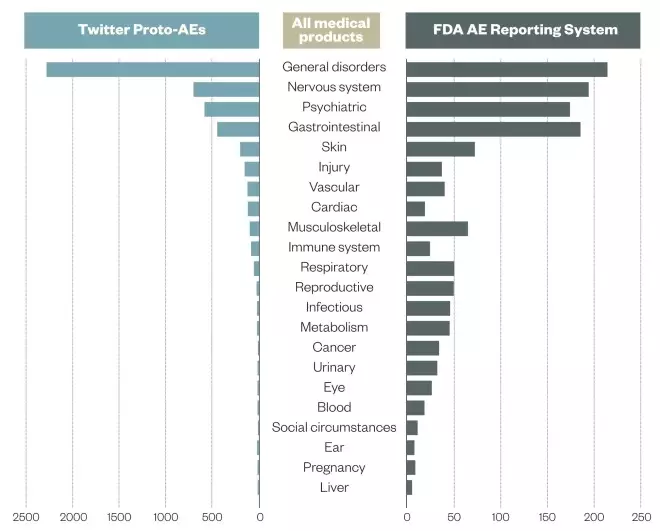

A 2014 study, funded by the FDA and involving Epidemico, examined 6.9 million Twitter posts and found 4,401 tweets that resembled an ADR. When compared with data held by the FDA, the study found a high concordance between the data across organ classes[1]

(see ‘Monitoring drug safety using Twitter’).

Monitoring drug safety using Twitter

Source: Drug Safety 2014;37:343-350.

Researchers collected 6.9 million Twitter posts, identifying 4,401 posts with resemblance to an adverse event (known as ‘Proto-AEs’). An analysis of the Proto-AEs found concordance with consumer reports in the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event (AE) Reporting System at the system organ class level (note log-log scale)

In another social media project that involved Novartis, a team of researchers trawled 250,000 social media posts for 250 medicines in the EU. It found 12,000 posts that could be a possible ADR report, which were whittled down to 1,500 ADR reports.

Nabarun Dasgupta, co-founder of Epidemico, says there is a high concordance between informal adverse reaction reports made on social media and those reported in clinical trials

For the past three years, Epidemico has also been tracking mention of all new medicines on social media, and claims there is a high concordance between informal adverse reaction reports made on social media and those reported in clinical trials. Epidemico says it has also picked up some new information on social media posts on Biogen’s oral multiple sclerosis drug, Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate), and herpes skin infections, data of which it presented at a conference in January 2014. “Other oral MS drugs like Gilenya had two people die [from herpes infections] in clinical trials and have [a]… warning to vaccinate patients against chicken pox [caused by the herpes virus varicella-zoster virus] before taking the medicine. But Tecfidera did not have that warning because no cases had been reported and encountered in the clinical trials, ″ says Nabarun Dasgupta, co-founder of Epidemico. In the past few weeks, it has also noticed social media posts on Tecfidera and oral thrush.

If we could advise the patient taking a steroid earlier about these food cravings we could possibly avoid the weight gain in the first place

When Epidemico studied the synthetic glucocorticoid prednisolone and prednisone,

patients taking it commented on social media that they had food cravings and were “feeling starved all the time”, while the traditional regulator’s database had noted “weight gain”. “If we could advise the patient taking a steroid earlier about these food cravings we could possibly avoid the weight gain in the first place,″ says Lewis. “I suspect the project will find other patient tolerance issues that are not reported to doctors. The project hopes to augment traditional ADR reporting.”

Other companies are also analysing social media to find potential drug safety signals, for example, Treato, a company based in Israel, and IMS Health, which is based in the United States.

“We have seen that the earliest references to problems such as adverse events and drug interactions appear in patients’ online conversations,″ says Ido Hadari, chief executive officer of Treato, which was set up in 2007. The company offers a reporting tool so that organisations can log these ADRs and its website allows patients to search for information that has been collated about particular drugs. “Our overall goal is early drug signal detection and improved patient outcomes,” says Hadari.

IMS Health has been analysing social media since 2013, when it acquired Semantelli, a social media analytics company, which was founded in 2009 in Bridgewater, New Jersey. “We have picked up new signals on many prescription and over-the-counter drugs,” says Siva Nadarajah, general manager of social media at IMS Health. “More importantly, we have picked up signals on efficacy about drugs that are not available through traditional sources, as ADR reporting rarely captures ineffectiveness of a drug.” IMS Health sells its technology to pharmaceutical companies, which use it to track ADRs in social media and other unstructured data sources found in patient support programmes.

Big Brother

The Web-RADR project started in September 2014 and is funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative, which in turn is funded by the European Commission and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. The initiative involves drug regulators, pharmaceutical companies, the World Health Organization and universities.

One of the main objectives of the project is to address the ethics of mining people’s posts for drug safety data. And crucially, whether people who make posts resembling an ADR should be contacted to encourage them to submit a formal ADR report. And if people are to be contacted, should this be done by drug regulators, pharmaceutical companies or a third party?

Although the FDA doesn’t contact social media users as part of a formal process, Epidemico contacted dozens of people who mentioned “ambiguous, but serious events” over one week, asking if they would mind submitting a formal report to the FDA. “[It] was fairly positive in terms of ‘Oh wow, that is so cool that you are listening’, but a couple of people have said ‘That’s creepy’. But at the end of the day, people didn’t submit additional follow-up information,” says Dasgupta. He adds that it will take close coordination with patient advocacy groups to understand the correct way to do the follow-up.

Dasgupta thinks people would feel uncomfortable if a regulator or pharmaceutical company contacted them and believes the job is best suited to a “respected, scientifically oriented and transparent third party”. But to create such a body is going to take a tremendous amount of political capital and will, he says.

The Big Brother idea is out there and we need to make sure that people do not fear being under surveillance without having being informed about it

Houÿez is also concerned about the perception of monitoring social media for drug information. “If the regulator contacts the person making the post, then we may see a negative reaction from the user, who may not appreciate that sort of surveillance,” he says. “The Big Brother idea is out there and we need to make sure that people do not fear being under surveillance without having being informed about it.”

The most desirable outcome, says Houÿez, is for pharmacovigilance experts at the EMA to communicate information about medicines to patients. For example, if the Web-RADR project picks up a tweet resembling an ADR, it could automatically tweet a person, saying: “We are a group of pharmacovigilance experts and we have detected a possible adverse drug reaction. Please visit this website to understand why you have received this link.”

Paul Bernal, a privacy expert who sits on the advisory board of the Open Rights Group, warns that contact with the social media user can’t be made by a drug company representative as there is distrust of the industry — ”rightly or wrongly”

Paul Bernal, a privacy expert and law lecturer at University of East Anglia, warns that contact with the social media user “can’t be made by a drug company representative as there is distrust of the industry — rightly or wrongly”. Bernal, who sits on the advisory board of the Open Rights Group, which raises awareness about digital rights abuses and threats, adds that if contact is made with the post-maker by an independent pharmacologist or the drug regulator and it is clear it is to help collect information about the safety of drugs “then it should be OK”.

The jury is out on who will do the contacting, if at all, according to Mick Foy, group manager of the vigilance, intelligence and research group at the UK’s regulator the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and project manager of Web-RADR. He says that the pharmaceutical industry has its own concerns about having to contact patients. “Some don’t want to be seen as marketing. And what are the implications once they have engaged with a patient? It is very difficult in an ADR scenario because you don’t know first hand the medical history of that person [and] whether they have spoken to their doctor.”

Lewis, from Novartis, points out that pharmaceutical companies are not allowed to make contact with patients without seeking permission from the patient and prescriber first. “Even then, it could be perceived as Big Pharma pursuing a patient… I am not sure that it should necessarily be the company [that contacts a patient].”

While the concept is legal, this becomes irrelevant if certain aspects of it upset people

Bernal has concerns that trawled data might be used for purposes other than identifying side effects. For instance, companies could ward off news stories on side effects if they learn about an adverse reaction before the regulator. He also believes that if people feel their posts are being monitored, they could be less forthcoming in talking about side effects. “While the concept is legal, this becomes irrelevant if certain aspects of it upset people,” he says. “The project needs to talk to people first and get the online community on board for it to work. If drug companies are going to do something dodgy, then we may get less information from patients about side effects [rather than more].”

IMS Health contacts patients via social media to ask them to fill in a formal ADR report and says that the response is relatively high if the ADR is reported on a company-sponsored social media channel, such as a sponsored patient community on Facebook or Twitter. “We also have a trusted Facebook application to obtain the information in a more structured way,” says Nadarajah. Treato is not currently contacting social media users.

Private message

Ethics aside, there are privacy and data protection issues to consider. Data protection laws in the UK and the European Union do potentially allow the use of personal data on social media for statistical and scientific purposes, says Jon Baines, chairman of the National Association of Data Protection Officers, as long as it is not used to make decisions about individuals. “If the data derived from this activity is anonymised, it should be OK,” he says.

But the idea of contacting someone following a tweet raises interesting questions for Baines. “For instance, would reliance on the exemption from data protection law for those statistical and scientific purposes be undermined?” he says. “And if public authorities are involved, and they are regularly monitoring specific social media accounts without individuals’ knowledge, then that could potentially be seen as direct surveillance engaging human rights law.”

Mick Foy at the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency says if you’ve put your social media in a public space it’s fair game and anyone can look at it

Foy argues that, if you’ve put your social media in a public space, it’s fair game and anyone can look at it. “I think everyone knows social media is trawled for a whole host of reasons, including marketing, security, etc. I don’t have any concerns about our ability — ethically or data protection wise — to mine the data and observe what is happening,” he says. “The concerns that need to be addressed are around a two-way engagement process. That is what the [Web-RADR] project will look at.”

Under European Union pharmacovigilance rules, there is no obligation on companies to monitor social media. However, if they look and find side effects, they must report them to regulators. Companies are legally obliged to monitor for side effects on websites or Facebook pages that they are responsible for or sponsor. Currently, some companies are actively engaged with social media and others are not looking for fear of having to report something they might find that is of little value.

Urban translator

There are signs that social media is proving more useful for signal detection rather than signal assessment, which has a slightly higher bar. “When you have a signal, then you can investigate it, you look at the literature, you do observational studies,” says Foy.

The Web-RADR project is expected to trawl for around 12 drugs, new and old, but the actual number of drugs is still to be agreed.

There are some major challenges to overcome in turning large volumes of unstructured and often low-quality data into information that can be used for signal detection, such as natural language processing, and the detection of duplicates, false positives and fraudulent posts. Extracting the drug name will be a challenge. For example, “Rachel” misspelt one of the antidepressants in her tweet. But even more difficult will be converting the social media vernacular of an adverse event into something pharmaceutical scientists understand.

If you do not have a sophisticated natural language processing system it will actually pull in a lot of information that is noise

A human curation step will take out false positives and the internet vernacular will be translated into the international medical dictionary, MeDRA (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities) coding. “We have created a large dictionary that has slang terms, hashtags, jargon and it matches these to the corresponding medical term in MeDRA,” says Epidemico’s Dasgupta.

“If you do not have a sophisticated natural language processing system it will actually pull in a lot of information that is noise. [We must ensure] we are not counting too many or too little,” says John van Stekelenborg, director of lead methods and analysis at Johnson & Johnson global medical safety, who is also involved in the Web-RADR project. Lewis adds: “Companies are a little worried about what the project finds if it loosely trawls for data”.

A separate algorithm will be developed with the help of the World Health Organization’s Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC) to identify potential duplicates in the Web-RADR mining tools.

“So if you tweet something and I retweet it, we are not counting it [twice]. If you tweet something, then Facebook it as well and put it in a blog as well, this is where the UMC algorithm will hope to pick it up so we are not counting that as three posts,” says Foy.

Once data from social media posts are captured by the Web-RADR data mining tools, they will be analysed by the regulator (EMA) and drug companies in the consortium to decide how they will be used. Who owns the data has still to be worked out. As a patient group, Eurordis advocates that all data from social media is added to the EU’s pharmacoviligance ADR database, EudraVigilance, which is freely accessible to patients and researchers, to aid signal detection. “The pharmaceutical industry needs to trust the system is accurate, but there could be mistakes and duplicates. The algorithms used to capture the data need to be well-defined and the industry needs to be confident with them. Eurordis would not favour a system where the industry received the ADR data solely,” says Houÿez.

Van Stekelenborg is adamant that monitoring social media won’t supplant the traditional ADR reporting systems. “We have various tools at our disposal, such as clinical trials, post-marketing spontaneous reporting and patient registries that can monitor safety, so this would be one additional tool in the toolbox,” he says, adding: “It remains to be seen what the value of social media is in this field.”

References

[1] Freifeld CC, Brownstein JS, Menone CM et al. Digital drug safety surveillance: monitoring pharmaceutical products in Twitter. Drug Safety 2014;37:343–350.