Courtesy of Ade Williams

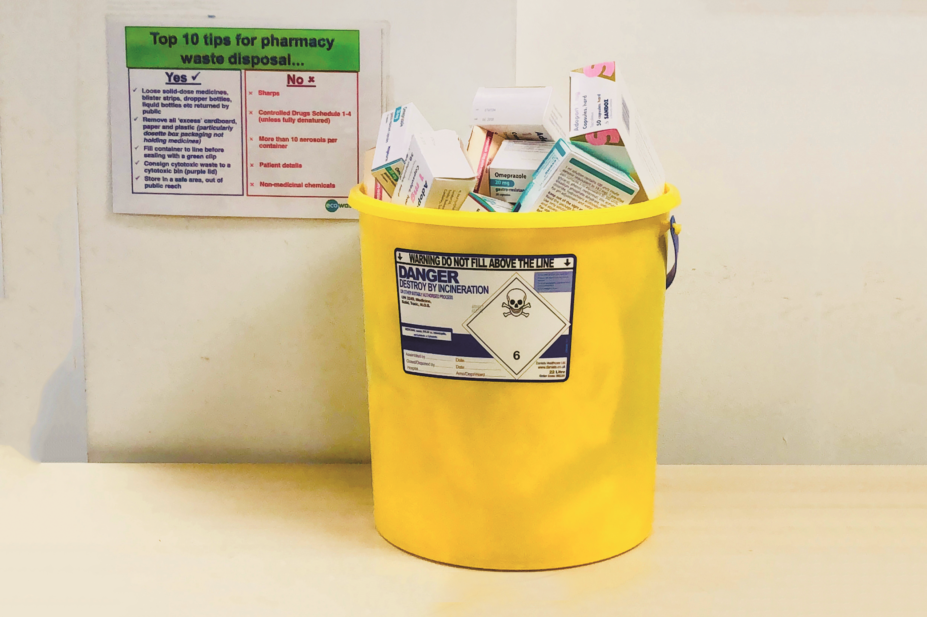

Most pharmacists will be familiar with the frustration that comes from sorting through medicines returned by patients, often in pristine condition and sometimes worth thousands of pounds, knowing that they are heading for the incinerator. But is there another way to deal with patient returns?

Medicines reuse schemes already operate successfully in the United States and Greece (see Panel 1), with the main driver being to help those who cannot afford to buy the medicines they need. Although the same impetus does not exist in the UK, there is still a need to reduce spending on drugs.

The Public Accounts Committee in Wales recently suggested using technology to enable re-dispensing of unopened medicines, and several academic groups are researching the potential for such a scheme in the UK and elsewhere.

“Even though we have the NHS in the UK, we know that there are medicines that aren’t made freely available because they are not deemed to have a significant enough impact on quality-adjusted life years, based on the acquisition cost of that drug,” says David McRae, pharmacist team leader for unscheduled care at Cwm Taf University Health Board, who is conducting research on re-dispensing returned medicines.

Source: Courtesy of David McRae

David McRae, pharmacist team leader for unscheduled care at Cwm Taf University Health Board, has surveyed pharmacists about their views on medicines reuse

“If it was known at the outset that a proportion of that cost to the NHS could be taken away because we would be able to reuse a certain amount, would that mean we would be able to extend access to those medicines?” he says.

If it was known at the outset that a proportion of that cost to the NHS could be taken away because we would be able to reuse a certain amount, would that mean we would be able to extend access to those medicines?

In 2009, medicines waste in England was estimated to cost the NHS £300m per year, including £90m worth of unused prescription medicines stored in peoples’ homes, £110m returned to community pharmacies, and up to £50m from care homes[1]

. This waste arises for many reasons, including overprescribing, lack of adherence, a change of treatment, or the patient dying. The proportion of waste considered avoidable was estimated to be between 30% and 50%.

But the cost of wasted medicines is not the only issue; their environmental impact also needs to be considered. Medicines have been found in surface waters, such as lakes and rivers, but also in groundwater, soil, manure and even drinking water.

“The majority of people dispose of their unused medicines in the bin or by flushing them down the toilet, and this can have a huge impact on the environment,” says Parastou Donyai, a pharmacy practice researcher at the University of Reading. “There is work that has looked at, for example, antibiotic resistance in wastewater.”[2]

Source: Courtesy of Parastou Donyai

A survey conducted by Parastou Donyai, a pharmacy practice researcher at the University of Reading, supports the hypothesis that there would be public demand for medicines reuse

A 2014 global review of pharmaceuticals in the environment, commissioned by Germany’s environment ministry, found that of the 713 pharmaceuticals tested for, 631 were found above their detection limits[3]

. A study from the University of York, published in June 2018, recorded very low levels of 29 different drugs in York’s rivers, including antidepressants, antibiotics and epilepsy medicines, although medicines in urine also contribute to the presence of pharmaceuticals in wastewater[4]

.

Panel 1: Medicines reuse schemes in the United States and Greece

SafeNetRx in the United States

In the United States, there are programmes that allow unused prescription drugs to be donated and redispensed to patients. Legislative change for such programmes began in 1997 and, as of October 2017, Guam, along with 37 US states, had enacted donation and reuse laws, 20 of which have operational programmes.

Most state programmes have several criteria in common:

- No controlled drugs;

- No adulterated or misbranded medication;

- All medicines must be checked by a pharmacist prior to being dispensed;

- All medicines must not be expired at the time of receipt — often they must have six months or more before expiration;

- All medicines must be unopened and in original, sealed, tamper-evident packaging;

- Liability protection for both donors and recipients is usually assured.

One such programme is Iowa’s SafeNetRx, which started in 2007 and was developed by the Iowa Department of Public Health. Donations are received from long-term care dispensing pharmacies, medical facilities and individuals.

A licensed pharmacist inspects donated prescription drugs and supplies to determine “to the extent reasonably possible in the judgement of the pharmacist” that the drugs and supplies are not adulterated or misbranded, are safe and suitable for dispensing, and are not ineligible drugs.

Any pharmacy or medical facility with authorisation to dispense may redispense donated medications. So far, the SafeNetRx programme has dispensed US$15m worth of prescription medicines to 70,000 patients in need.

GIVMED in Greece

In operation since 2016, GIVMED is an innovative service based in Athens, Greece, that coordinates donations of unused medicines.

A mobile app enables users to register their excess medicines by scanning the barcode on the packaging. It then connects them with institutions that can distribute the medicines to individuals in need, such as government-funded social pharmacies, akin to food banks in the UK, and care homes.

“We do not charge the institutions that access the medicines, nor the individuals who donate medicines,” explains Thanasis Vratimos, strategy and operations coordinator at GIVMED.

Pharmaceutical companies, institutions and individuals can donate to the scheme and pharmacists then check the donated medicines to ensure they meet specified criteria.

“In Greece, we have found a way to accept medicine donations from individuals and I’m sure that other countries that want to do it could find a way to overcome the problems,” says Vratimos.

GIVMED is funded by foundations, individuals and companies (not pharmaceutical). Since 2016, 19,432 boxes of medicines worth €201,822 have been donated via 120 donation spots, meeting 3,329 medicines requests.

Source: Courtesy GIVMED

Professional guidelines

Of course, a lot of people already return their unused medicines to community pharmacies for safe disposal. Some of these medicines are in their original packaging and well within their expiry date. Adam Mackridge, a pharmacist at Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board, has published research that suggests 25.3% of patient returns would meet criteria for reuse[5]

. A similar study in the Netherlands found that 19.1% of medicines were eligible for re-dispensing[6]

.

Finding a way to return these medicines back into the supply chain may seem like a no-brainer. However, there are several reasons why such schemes may be difficult to implement in the UK.

At first glance it can seem a really worthwhile area; however, there are lots of considerations around getting those medicines into a state where they can be reused

“At first glance it can seem a really worthwhile area,” says Andy Cooke, interim practice and policy lead for England at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS). “However, there are lots of considerations around getting those medicines into a state where they can be reused,” he explains.

Source: MAG / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Andy Cooke, interim practice and policy lead for England at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, believes that the effort required to implement medicines reuse would be better spent on appropriate deprescribing and improving medicines adherence

The General Pharmaceutical Council does not have specific guidance on medicines reuse, but its standards for registered pharmacies would appear to preclude it, stating that medicines must be: obtained from a reputable source; safe and fit for purpose; stored securely; and safeguarded from unauthorised access.

The RPS and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) say that medicines should not be reused because of concerns over quality.

“Human medicines should not be reused after dispensing to a patient, as the conditions under which the products have been stored are unknown and, as such, the quality, safety and efficacy of the medicine cannot be guaranteed,” explains an MHRA spokesperson.

“Patient safety is paramount. In the current system we cannot see how reuse of medicines would maintain assurance of quality,” adds Cooke.

However, the government was willing to relax its position on medicines reuse in 2008 when, with an influenza pandemic looming, the Department of Health issued guidance, backed by the RPS, permitting reuse of expired or returned medicines, should a certain severity of pandemic hit.

Quality issues

Researchers in the field challenge the longstanding view about the quality of returned medicines being compromised.

“If somebody leaves the pharmacy with their own medication and we can’t trust the integrity of the product in their hands, why would that medicine be OK for them [but not for someone else],” asks Donyai.

If somebody leaves the pharmacy with their own medication and we can’t trust the integrity of the product in their hands, why would that medicine be OK for them [but not for someone else]

“A further paradox is that we give people medicines once they’ve been dispensed into monitored dosage systems, which arguably could have a greater impact on the stability of these tablets,” she adds.

Mackridge agrees, describing the quality argument as a “red herring”: “If we are that confident that patients frequently store medicines [inappropriately], why are we not more concerned about the impact that this might have on their own health?”

Moreover, medicines packaging has changed significantly over the past three decades, with most medicines now dispensed in sealed blister packs within cardboard boxes that are designed to withstand changes in humidity and light. Temperature-sensitive stickers also now exist that can be applied to packaging to indicate whether it has been stored at an ambient room temperature. These stickers are already widely used within the pharmaceutical industry to ensure that products requiring refrigeration have been stored correctly during transportation.

“We want to understand whether medicines stored in people’s homes in their original packs for a short time actually deteriorate,” says Donyai. She has conducted some laboratory-based research, which found that when medicines were stored at a raised temperature in their original packaging, their chemical stability was not affected. “I would like government support to help update knowledge in this area, for example, through research funding,” she says.

We want to understand whether medicines stored in people’s homes in their original packs for a short time actually deteriorate

Although researchers may not be overly concerned about the quality of medicines being compromised, a survey of 1,003 people, conducted by Donyai and colleagues, suggests that it is an issue for some patients. Respondents were worried about receiving low-quality (58%), unsafe (57%) or incorrect (60%) medicines[7]

.

And it is not only inappropriate storage conditions: the possibility that medicines may have been maliciously tampered with is another reason cited by the public, regulators and healthcare professionals for not reusing medicines.

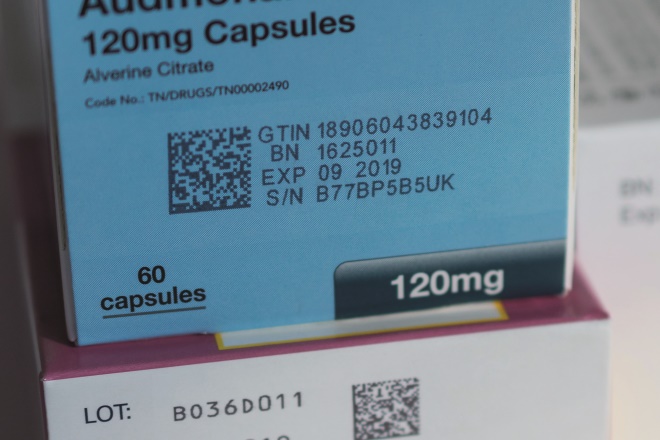

Falsified Medicines Directive

“The concern around tampering should be addressed with the introduction of the Falsified Medicines Directive (FMD) in February 2019, which will require all medicinal products to have an anti-tampering device,” points out Delyth James, pharmacist and principal lecturer in health psychology at Cardiff Metropolitan University, who is researching pharmacist and patient views on medicines reuse along with McRae.

Source: Courtesy of Jonathan Buisson

Reusing medicines could undermine the Falsified Medicines Directive, which will mandate use of 2D barcodes to track medicines from manufacturers to patients

However, the FMD could also present problems for any potential reuse scheme. “The possibility of counterfeits and maliciously tampered with medicines is one of the biggest problems we would have to overcome,” says Mackridge.

The possibility of counterfeits and maliciously tampered with medicines is one of the biggest problems we would have to overcome

The FMD is designed to make the pharmaceutical supply chain more secure by tracking medicines from the manufacturer to patients.

“If a medicine is returned to the pharmacy it should be placed back in the database. I think that option is not there yet and it will probably be difficult to introduce it,” says Charlotte Bekker, a researcher at University Medical Centre Utrecht in The Netherlands.

The Welsh government has also acknowledged that reusing medicines would undermine the benefits of the FMD.

Donyai hopes that there could be a way to integrate reuse within the FMD. “My understanding is that there would be some scope for looking at the 2D barcode and looking at what other information could potentially be stored within that, for example, a system to allow medicines to re-enter the chain,” she says.

Economic viability

Another barrier to the reuse of medicines is whether any scheme would be economically viable. Bekker and her colleagues have studied the potential costs of a medicines reuse scheme.

Source: Courtesy of Charlotte Bekker

Charlotte Bekker, a researcher at University Medical Centre Utrecht in The Netherlands, has studied the potential costs of a medicines reuse scheme

“We identified which activities pharmacists should perform and the labour and material costs of those activities,” she explains. “We found that it is most cost beneficial if it is applied to expensive medications that require room temperature storage; for example, oral anti-cancer medicines.”

We found that it is most cost beneficial if it is applied to expensive medications that require room temperature storage; for example, oral anti-cancer medicines

Their research revealed that it is unlikely to be cost effective to include medicines below €100 per packet. But this depends on the amount of dispensed medicines that are returned to the pharmacy. If 5% is returned, of which 60% fulfils the quality criteria, the price level is €101 per package for medicines requiring room-temperature storage. However, if 10% is returned, of which 60% fulfils the quality criteria, the price level decreases to €53.

Cooke stresses that if, in the future, assurances of quality and safety could be met, it would be crucial to weigh up the amount of work that would need to go into a process for medicines reuse with the cost of those medicines.

“There is a huge amount of infrastructure that goes into the [dispensing] process, so any changes to that could be sizeable around the impact on workload for individuals and any bureaucracy behind managing those medicines,” he says.

Political will

The Welsh government also recognised the cost implications of medicines reuse when it rejected a recommendation from the Public Accounts Committee in March 2018 to plan for “the emerging technologies in prescription packages facilitating the use of unopened medication[8]

”.

“At the current time, the costs associated with temperature-sensitive packaging are likely to be prohibitive to their widespread use, particularly when the low mean (£7.28) and even lower median cost of prescribed medicines (£1.59) is taken into account,” the government said in its response[9]

.

James believes that further research and a narrowing of the scope of any scheme might change the government’s view.

Source: Courtesy of Delyth James

Delyth James, pharmacist and principal lecturer in health psychology at Cardiff Metropolitan University, is hopeful that further research and a narrowing of the scope of any medicines reuse scheme might change the Welsh government’s view on the idea

“There is not a political will at the moment to introduce it as a blanket scheme in Wales but I think maybe there is scope to narrow it down [to expensive drugs and care homes] in terms of taking it forward,” she says.

There is not a political will at the moment to introduce it as a blanket scheme in Wales but I think maybe there is scope to narrow it down [to expensive drugs and care homes] in terms of taking it forward

In The Netherlands, the government is open to introducing a scheme, but it “strongly depends on if it is possible to implement a cost beneficial system”, says Bekker, explaining that the Ministry of Health indicated in May 2018 that the focus should be on prevention of waste, rather than redispensing “because redispensing is only attractive for expensive medicines”.

Is prevention better than cure?

The argument that efforts should instead focus on tackling the reasons behind medicines waste is backed by the RPS.

“Your gut feeling is that it’s wasteful [not to reuse medicines] but what would be the added value that [it] would create versus the opportunity costs,” asks Cooke. He believes that the effort required to implement medicines reuse would be better spent on appropriate deprescribing and improving medicines adherence.

He says that the lost health opportunity of wasted medicines is around £500m a year[1]

. “Tackling the causes of waste should remain the priority as this should also lead to improvements in health,” he says.

Tackling the causes of waste should remain the priority as this should also lead to improvements in health

However, Mackridge is more pragmatic. “We should tackle [things like] over-ordering, but I am concerned that the purist approach that some people have is unrealistic and leads to waste because we don’t live in a perfect world.”

Pharmacists’ views

McRae and James surveyed hospital, primary care and community pharmacists in Cwm Taf University Health Board, seeking their views on the prospect of medicines reuse[10]

. They identified several key criteria that would need to be met in order for pharmacists to accept a re-dispensing scheme.

“There would need to be liability arrangements for individual pharmacists before they would consider redistributing [and] there would also need to be guidance from the professional regulator,” says McRae.

“Medicines would require tamper-evident seals, and only ‘as new’ packaging would be re-dispensed.”

The pharmacists also agreed that some technologies, such as irreversible temperature-sensitive stickers, should be used. “The final criterion was that there would need to be extensive public consultation and education around any scheme,” says McRae.

Next steps

Donyai agrees that public consultation is key and is keen to get the public, stakeholders and politicians talking about medicines reuse.

“We hope to engage with the relevant stakeholders and really open the public debate about this, and that debate at a policy level,” she says.

In recent years, there has been a noticeable shift towards trying to reduce our waste, for example through refillable coffee cups and reusable shopping bags, and to reuse unwanted possessions through websites such as EBay and Gumtree. Perhaps this cultural shift could extend to medicines.

Donyai’s survey found that more than half of respondents intended (55%) or wanted (57%) to reuse medicines in the future. “So our work would support the hypothesis that there would be public demand for medicines reuse,” she says[7]

. More than half of those surveyed thought that reusing medicines would be beneficial and worthwhile. Almost three-quarters believed medicines reuse would reduce the harmful effect of medicines waste on the environment, with 79% saying it would reduce NHS medicines spend.

Our work would support the hypothesis that there would be public demand for medicines reuse

These findings correlate with unpublished data from The Netherlands, where a recent survey by Bekker and colleagues found that 60% of the 2,200 people questioned were positive about the idea of reusing medicines.

McRae and James are also canvassing the public’s views. The pair are currently conducting a survey via Healthwise Wales, a Welsh government initiative that seeks to connect health service researchers with the public. The survey is due to close in October 2018 after a year, and currently has over 3,000 respondents.

“Hopefully it will give us a really nice understanding about how the public view this issue and how people store their medicines,” explains McRae.

If the Healthwise Wales data are positive, the next phase would be a feasibility study.

Mackridge is convinced that the vast majority of challenges around medicines reuse can be overcome.

“If someone is willing to look at it with some real will to solve the problems, I think it’s perfectly possible to reuse medicines in the UK.”

Panel 2: Views from frontline pharmacists

“I can understand the benefits of the current system, as soon as a product leaves the pharmacy we can no longer guarantee its integrity, therefore it cannot be reused. However, this is not a black and white issue. What if the item has only been dispensed 5 minutes or days earlier? Can the country afford to take an absolute approach to this? A possible solution is to allow pharmacists to use their professional judgement as to whether medication can be reused. Lots of thought would need to be put into this, and guidelines issued. A fee for this work should be negotiated by the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee, probably on a sliding scale depending on the value of the item being reused.” Peter James, a locum pharmacist in Wales.

“We see a lot of returns for a wide range of categories including omeprazole or blood pressure medicines patients no longer need. The trouble being sometimes GPs prescribe 2 or 3 months’ worth, or the patient simply doesn’t take them as they’re prescribed, hoards them and returns them. And a lot of the time they return items thinking that we can recycle them. I think a medicines reuse scheme would be an excellent idea. However, there will be safety issues and checks required to ensure the returned stock is not compromised or controlled drugs/fridge items, etc. A good idea but a difficult one to monitor.” Andrew Cheung, a community pharmacist in Belfast.

Source: Courtesy of Andrew Cheung

Andrew Cheung, a community pharmacist in Belfast, believes that reusing medicines is a good idea but it would be difficult to monitor

“In my view, medicine waste recycling schemes would only work if we can get an innovative way to guarantee the quality of the returned medicines. In addition, the bigger challenge is in identifying the causes of this waste. We would need to revamp the way we manage prescriptions for long-term conditions, such as increasing use of tools like electronic repeat dispensing, which allows controlled release of monthly prescriptions without increasing GP workload and enables both GP and pharmacy teams to make interventions and modifications.” Emmanuel Chisadza, a locum pharmacist in Hampshire and Dorset.

“The amount of medicine waste we see is because of a variety of reasons, not always preventable, but ultimately, all returned medicines have to be incinerated and destroyed. It’s a colossal waste. I have always been wary of recycling schemes although I have seen them work in the US; the risk of public trust in the UK pharmacy is my main concern. However, I note that there is now a fundamental change in society’s view of waste and wastefulness occurring. With the barriers [around quality and safety] addressed, the option to offer use of appropriate returned unopened medicines may even be cautiously supported by the public.” Ade Williams, a community pharmacist in Bristol.

“We receive quite a lot of waste, and lots of dressings. For drugs alone, we send approximately three 15kg bins for incineration each week, and recycle inhalers through a GSK scheme. I think it would be inappropriate to reuse drugs, as the safety of this cannot be guaranteed. However, for dressings and appliances, we sometimes offer them to the local vets or charities. If they could be reused in the NHS, for example by district nurses, this would save money.” Liam O’Sullivan, a community pharmacist in Southampton.

References

[1] York Health Economics Consortium and the School of Pharmacy University of London. Evaluation of the scale, causes and costs of waste medicines. November 2010. Available at http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1350234/1/Evaluation_of_NHS_Medicines_Waste__web_publication_version.pdf (accessed July 2018).

[2] Schwartz T, Kohnen W, Jansen B & Obst U. Detection of antibioticâ€resistant bacteria and their resistance genes in wastewater, surface water, and drinking water biofilms. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2003; 43: 325– 335. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2003.tb01073.x

[3] Weber F-A, aus der Beek T, Bergmann A et al. Pharmaceuticals in the environment — the global perspective. German Environment Agency; December 2014. Available at https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/378/publikationen/pharmaceuticals_in_the_environment_0.pdf (accessed July 2018).

[4] Burns EE, Carter LJ, Kolpin DWet al. Temporal and spatial variation in pharmaceutical concentrations in an urban river system. Water Research 2018;137:72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.02.066

[5] Mackridge A & Marriott JF. Returned medicines: waste or a wasted opportunity? Journal of Public Health 2007;29:258–262. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm037

[6] Bekker CL, van den Bemt BJF, Egberts ACG et al. Patient and medication factors associated with preventable medication waste and possibilities for redispensing. Int J Clin Pharmacy 2018;40:704–711. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0642-8

[7] Alhamad H, Patel N & Donyai P. Beliefs and intentions towards reusing medicines in the future: a largeâ€scale, crossâ€sectional study of patients in the UK. Int J Pharm Pract 2018; 26 (suppl 1):12. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12442

[8] National Assembly for Wales Public Accounts Committee. Medicines management. March 2018. Available at https://www.assembly.wales/laid%20documents/cr-ld11478/cr-ld11478-e.pdf (accessed July 2018).

[9] Response to the recommendations contained in the report of the National Assembly for Wales Public Accounts Committee entitled medicines management. Available at http://www.assembly.wales/Laid%20Documents/GEN-LD11534/GEN-LD11534-e.pdf (accessed July 2018).

[10] McRae D, Allman M & James D. The redistribution of medicines: could it become a reality? Int J Pharm Pract 2016;24:411–418. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12275