shutterstock.com / JL

From dealing with minor illnesses to handling potentially life-threatening overdoses, it takes a particular type of pharmacist to work at NHS 111, the 24/7 telephone service.

“It’s important that they are well-rounded pharmacists so that they can deal with calls, [because] some can be inappropriate or upsetting,” says Margaret McGee, regional pharmacy adviser at NHS 24 (West), the Scottish version of NHS 111. She recalls a variety of scenarios she has been involved with, from a snake bite on the Orkneys to a child who had swallowed what was thought to be a piece of Lego (which she later discovered was an ecstasy tablet shaped like the toy brick).

On account of the nature of the role, McGee explains, it is important to be “quite a solid person”.

NHS 111 (or ‘NHS 24’ in Scotland) is for people whose healthcare needs are urgent, but who do not require the emergency services accessed via calling 999[1]

. It was brought in to replace the nurse-led NHS Direct service, which was launched in 1998 as a means of relieving pressure on GPs and A&E departments.

The service was first piloted in 2011 before it was rolled out across England by the end of 2013, with roll outs following in Scotland and parts of Wales. The latest figures for England show that in June 2019, an average of 43,900 calls were made per day to NHS 111[2]

.

However, despite the volume of calls, NHS 111 referrals to pharmacy have taken a while to get going. By 2015, less than 1 caller per 100 in England was advised to speak to a pharmacist. And, despite lobbying from organisations such as the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) and the now disbanded Pharmacy Voice, this had barely changed since the national roll out four years before.

Some commentators blamed the lack of pharmacy involvement on the switch from NHS Direct to NHS 111, saying that dispositions for pharmacy — and for clinical assessment in general — that existed in NHS Direct were lost in the move to NHS 111.

However, by April 2018, referrals to pharmacy had doubled, with figures showing that 2.5% of total NHS 111 referrals in England were to pharmacy. Now, backed by government funding, there are plans to extend the role of pharmacists further.

Developments to the NHS 111 service have enabled more and more streaming to pharmacists within the clinical assessment service, and also to community pharmacy for minor health concerns

“Developments to the NHS 111 service have enabled more and more streaming to pharmacists within the clinical assessment service [CAS], and also to community pharmacy for minor health concerns,” explains Anne Joshua, head of pharmacy integration at NHS England.

“Pharmacy colleagues have embraced the changes, and additional funding from the Pharmacy Integration Fund (PhIF) has increased the number of pharmacists working alongside other healthcare professionals within the CAS,” she adds.

But the role of pharmacists in NHS 111 is not just being expanded across England. Scotland and Wales have developed their own versions of the NHS 111 service, with their own sets of algorithms, and pharmacists play an essential role in these too.

The Welsh approach

Alexandra Gibbins, professional lead for NHS 111 pharmacists in Wales, says that when developing the Welsh service — which was piloted in October 2016 and then rolled out in April 2018 — the team looked at England, Scotland and then further afield to New Zealand, for inspiration.

“[We] took the best bits from all of those [services] … and tried to build a service that was really only similar in number to the 111 service in England.”

The team decided to put in place a ‘clinical support hub’ because it felt there needed to be more clinical than non-clinical advisers, says Gibbins. This hub spans the front end of the service, which is hosted by Welsh ambulance services, and the back end of the GP out-of-hours service, which is the responsibility of the Welsh health boards.

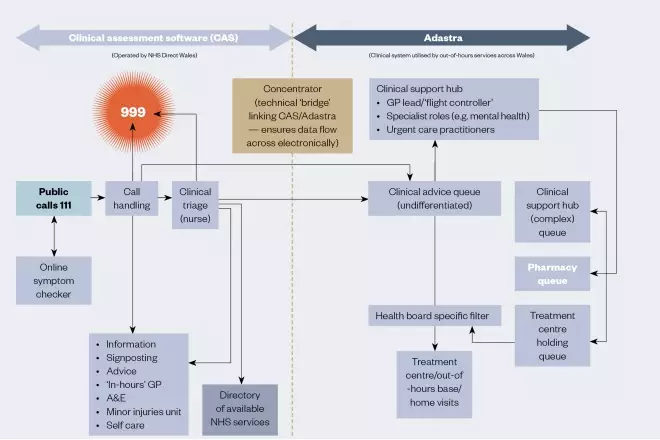

In Wales, pharmacists work within the clinical support hub. Calls are answered by call handlers who then determine the next steps (see Figure). If they decide the caller needs to see a clinician, that information is passed through and the call lands in a queue.

Figure: Welsh NHS 111 service model

Source: National 111 programme, Wales

Calls are allocated to the pharmacist via the clinical support hub. NHS 111 pharmacists deal with a range of issues, including medicines queries, missed doses and requests for repeat medicines, as well as common acute illnesses

It’s not community pharmacy on the telephone; NHS 111 pharmacists have to have a higher level of skill, which is where the transition programme comes in

“An overview of that queue is then looked at in the clinical hub by a clinical lead GP — we call them the ‘flight controller’ — they are looking at calls and will say which are suitable for a pharmacist,” explains Gibbins.

Pharmacists deal with a range of issues, from medicines queries, missed doses, requests for repeat medicines, as well as common acute illnesses, such as urinary tract infections, sore throats and skin problems, Gibbins explains. However, they also need to be skilled in ruling out more serious conditions.

“It’s not community pharmacy on the telephone,” she adds. “[NHS 111 pharmacists] have to have a higher level of skill, which is where the transition programme comes in.”

Gibbins has worked with the RPS in Wales to develop its transition programme, which was piloted in January 2018, to support Welsh pharmacists moving into careers within NHS 111. As part of this, she developed an NHS 111 knowledge toolkit for pharmacists undertaking the transition programme, which is evolving as the service in Wales grows.

“It needs to continue [to evolve]. As [pharmacists] get more involved clinically, we get more involved in incidents and near-misses, and we need to take the learning from those to update the toolkit,” she explains.

Pharmacists are given a set amount of time to complete the transition programme, which most do on top of their day job. Gibbins says she has to have assurance that they are “competent and confident practitioners” before they can move forward.

Gibbins is also helping to roll out the NHS 111 service across Wales. As of July 2019, NHS 111 has been rolled out to three of the seven health boards and there are plans to roll out to a fourth by the end of the summer. The rollout is phased so that each health board has time to recruit call handlers and clinical advisers, and carry out appropriate training before the number is “switched on”.

Ongoing monitoring shows that pharmacists working for the service may be successfully easing the growing pressure on GPs — around eight in ten calls to NHS 111 in Wales that are picked up by pharmacists are closed without the need for onward referral.

You don’t want someone sitting in a base for an eight or nine-hour shift when you’ve got an increase in demand for two hours; home working enables us to react quickly

A significant barrier to pharmacists doing more within the service is that it has not always been possible or easy for them to travel to the base call centre when call demand suddenly goes up, so Gibbins and colleagues are looking at ways to enable home working to maximise pharmacists’ benefit.

“You don’t want someone sitting in a base for an eight- or nine-hour shift when you’ve got an increase in demand for two hours. [Home working] enables us to react quickly,” she explains.

Another area for development is bringing pharmacists into treatment bases to consult with patients face to face. “When you book [patients] into bases, it’s a GP dealing with that. But pharmacists could be dealing with that.

“So that’s the next step — getting pharmacists in to [carry out] face-to-face [consultations].”

Source: Courtesy of Alexandra Gibbins, Anne Joshua, John O’Sullivan

From left: Alexandra Gibbins, professional lead for NHS 111 pharmacists in Wales; Anne Joshua, head of pharmacy integration at NHS England; and John O’ Sullivan, a pharmacist who is in the charge of the NHS 111 service in Kent, Medway, Surrey and Sussex

NHS 24

Like Gibbins, McGee — who line manages a significant proportion of the 23 pharmacists working within Scotland’s NHS 24 — believes that experience of different areas of pharmacy and considerable clinical skill are necessary to be successful within the service.

NHS 24 is nurse led with no GP involvement. Pharmacists sit within the clinical team, alongside physiotherapists and dental nurses, providing information to patients, carers and care homes. McGee says a large proportion of callers’ queries are straightforward, but there are instances when pharmacists have to deal with more complicated cases, such as accidental and intentional overdoses, sometimes involving young children.

When calls come in for patients aged under 18 months, they are automatically dealt with immediately. All other calls are prioritised according to the urgency of the case — Priority 1, Priority 2 and Priority 3. Call handlers go through a series of safety questions and algorithms, one of which leads to pharmacy.

“If [the call is referred to] pharmacy, there are two different options — serious and urgent. [The call handler] would then try to get hold of a pharmacist who would either take over the call or support the call handler with some advice [for the caller].”

We want to give parents an outcome, so … if they need a prescription, we could intervene as pharmacists to do that final step instead of the GP

The team may also receive calls via an automated part of the system that deals with non-urgent queries.

Pharmacists can take between 35 and 50 calls per 7.5 hour shift, but McGee assures that the focus is on safety, not call volume. She is keen to develop the service further by making more of independent prescribing, and is also leading a move towards remote prescribing — prescribing via telephone, video or online — particularly for children aged under 18 months.

“We want to give [parents] an outcome, so … if they need a prescription, we could intervene as pharmacists to do that final step [instead of] the GP.”

She says that the team is currently working on developing a formulary and process for remote prescribing, with a pilot that went live at the end of June 2019 already proving to be “exceptionally successful”.

In addition to developing current pharmacists, the NHS 24 service is also invested in training the next generation. “This year, we have final-year pharmacy students from Strathclyde University and third-year Robert Gordon University students [coming] to spend a week doing experiential learning, which is quite exciting. It’s not been done here before,” says McGee.

The English model

In England, the ‘NHS Long Term Plan’, published in January 2019, set out how NHS 111 is being enhanced so that patients can access urgent care services that are fully integrated[3]

. This means patients using the service who need clinical input will be transferred to an integrated urgent care clinical assessment service (IUCCAS) where they can speak directly to a clinician, such as a pharmacist, who will aim to complete the call without the need to transfer the patient elsewhere[4]

.

While there is just one service specification for NHS 111 and the IUCCAS in England, the services are commissioned locally, according to local need, with different levels of integration and pharmacy involvement.

John O’Sullivan, a pharmacist who is in the charge of the NHS 111 service in Kent, Medway, Surrey and Sussex, says that it is a “really interesting time” for pharmacists working within NHS 111 in England.

“Up until a year ago, pharmacists were not acknowledged as being NHS Pathways-licensed clinicians [and were not] able to use the NHS Pathways algorithm — only paramedics and nurses were — we worked hard with NHS Digital to change that guidance.”

Kent, Medway, Surrey and Sussex comprises seven clinical commissioning groups and its NHS 111 service receives 1.2 million calls per year. On 31 March 2019, the service joined up with the CAS, as part of NHS England’s wider plans to bring urgent care services within its integrated urgent care model.

“The clinical algorithms that underpin NHS 111 may refer patients into the IUCCAS for further telephone assessment by pharmacists, GPs, nurses, paramedics and other clinicians,” explains Joshua.

“Alternatively, NHS 111 may refer patients to other services, such as a community pharmacy or an urgent treatment centre,” she adds (see Box).

With this new operating model, we’ll be able to empower pharmacists to make an even bigger difference

Joshua says that the algorithms are continuously being updated and developed to incorporate clinical evidence and feedback from the service.

O’Sullivan welcomes the move to the clinical assessment service. “We’ve got some really good pharmacists and we want them to be able to work with a wider scope of practice and, with this new operating model, we’ll be able to empower them to make an even bigger difference,” he says.

However, what is happening in Kent, Medway, Surrey and Sussex is not indicative of the rest of the country. “Some providers absolutely get it and embrace the benefits that pharmacists can bring … then you’ve got other providers who don’t quite get it,” says O’Sullivan.

“People in urgent and emergency care tend to know what paramedics and nurses do, but they don’t always know what pharmacists do.”

But he believes that, with the development of the NHS England integrated urgent care pharmacy programme, the focus will be on having more pharmacists involved, rather than less.

Through the PhIF, which was set up in October 2016 to drive greater use of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians in integrated local care models, NHS England is funding 43 full-time-equivalent urgent care pharmacists in NHS 111 providers, working as part of the clinical team in the IUCCAS.

According to Joshua, there are also 115 pharmacists enrolled in an 18-month programme of practice support and training through Derby University, which includes qualifying as independent prescribers. The pharmacists enrolled in the programme work a minimum 0.4 whole-time equivalent in IUCCAS or NHS 111 roles.

“The training focuses on clinical assessment using telephone skills as well as prescribing training and physical assessment skills to underpin practice,” she says, adding that a significant part of the course is delivered online to facilitate shift working for the pharmacist teams and access to clinical supervision.

We do not have enough GPs in this country; the more cases we can direct to different skill sets, the better

Joshua is confident that the PhIF will continue to support training and evaluation of the IUC pharmacist role. “IUC and NHS 111 providers are positive about the role and keen to continue to develop the scope as part of the wider team.”

O’Sullivan says the potential for pharmacists within urgent care is “immense”.

“We do not have enough GPs in this country. The more cases we can direct to different skill sets — pharmacists, critical care paramedics, advanced nurse practitioners — the better.”

He adds that, in five years’ time, he believes pharmacists working for NHS 111 will be carrying out home visits and taking the lead on diverting patients to the most appropriate clinical setting.

After somewhat of a rocky start eight years ago, the NHS 111 service is now emerging as a valuable outlet by which pharmacists can channel their medicines expertise and enhance care for patients as part of a multidisciplinary team. And it appears that this role is set to grow across the three nations to help address continued pressures on primary and urgent care.

“As a profession [we] need to reflect on what transferable skills we can bring into what is an ever-changing market,” says O’Sullivan.

“You have to adapt to the sea you’re swimming in — that’s really important.”

Box: Referral from NHS 111 to community pharmacy

In March 2019, NHS England announced that the NHS Urgent Medicine Supply Advanced Service (NUMSAS) pilot, in which NHS 111 refers patients requiring urgent access to a medicine to community pharmacy, would be extended for the third time to September 2019.

“There have been only 4,000 pharmacy registrations as of March 2019 and we are convinced that this number can be substantially increased,” says Anne Joshua, head of pharmacy integration at NHS England.

“NHS England is working in partnership with the community pharmacy sector to maximise the opportunity, particularly for 100-hour pharmacies to take part.”

As of November 2018, NUMSAS accounted for 55% of total referrals for urgent repeat medication, compared with 31% for out-of-hours GP services.

The Digital Minor Illness Referral Service (DMIRS), which directs patients from NHS 111 to community pharmacy, rather than to hospital emergency departments or to GPs, is also being developed. This service was first piloted in the North East of England and has now been extended to London, Devon and the East Midlands.

“The evaluation is ongoing and will include feedback from pharmacists and NHS 111 providers involved in the pilots,” says Joshua, adding that the pilots will continue to inform this work initially up to the end of September 2019.

“The DMIRS may be extended and NHS 111 could start referring patients with minor illnesses to all community pharmacies to support urgent care,” she says.

References

[1] Dayan, M. Nuffield Winter Insight. Briefing 2: NHS 111. 2017. Available at: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-02/winter-pressures-nhs-111-final-web.pdf (accessed August 2019)

[2] NHS England. NHS 111 Minimum Data Set, England, June 2019. 2019. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/07/NHS-111-MDS-June-2019-Statistical-Note.pdf (accessed August 2019)

[3] NHS. The NHS Long Term Plan. 2019. Available at: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/nhs-long-term-plan-june-2019.pdf (accessed August 2019)

[4] NHS England. Developing the integrated urgent care/NHS 111 call centre workforce. 2017. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/urgent-emergency-care/nhs-111/urgent-care-workforce-development/ (accessed August 2019)