istockphoto.com

Matthew Chaddock first went to the doctor for trouble with his bowels when he was 13. But it wasn’t until about five years ago that he was finally diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) at the age of 26 years. “They said ‘there’s not much we can do for you, just play around with your diet’.” Chaddock felt let down. “I had the mentality that you go to see a doctor, they work out what’s wrong with you and then they say ‘right, do this and you’ll be cured’,” he says. “That isn’t the way it works with IBS.”

Source: Courtesy of Matthew Chaddock

Matthew Chaddock, who suffers from irritable bowel syndrome, feels let down because of a lack of treatment options for the condition

In fact, Chaddock’s experience is not unusual. IBS remains poorly understood and the drugs available to treat it usually offer symptomatic relief rather than tackling the underlying cause. Some scientists believe one reason IBS has proven hard to crack is because the cause of the syndrome probably differs from patient to patient — and understanding this may lead to better, more tailored, treatments.

A chronic condition characterised by at least six months of abdominal pain and bowel symptoms, such as diarrhoea, constipation, or a combination of both, many doctors regard IBS as a “diagnosis of exclusion”. As Chaddock says: “I started having various tests which came back negative and that’s when they said ‘it sounds like IBS’.”

Quality of life

Although it is not life threatening, IBS can have a huge impact on patients. According to Robin Spiller, a gastroenterologist specialising in IBS at the University of Nottingham, England, some sufferers with diarrhoea won’t even eat out, “because of the need to go to the toilet urgently after starting a meal, which is embarrassing”. But because IBS is not viewed as a “serious” illness, Spiller says drug regulatory authorities “don’t rate it highly”.

It is not only the regulators that have a blind spot when it comes to IBS. John Cryan, a researcher into interactions between the brain, gut and microbiome based at University College Cork in the Republic of Ireland, calls IBS “the unloved disorder” because “it’s the most common disorder that gastroenterologists will see and there’s so little understanding of it”.

It’s the most common disorder that gastroenterologists will see and there’s so little understanding of it

Around 10–20% of people in the UK are known to be affected by IBS, although the actual prevalence is probably higher. “The fraction [of people] that come to see their GP is small,” says Spiller, who believes sufferers mostly cope on their own. And while he thinks it is reasonable for some IBS sufferers to self-manage with over-the-counter treatments (see Table), he suggests that “people who are restricting their social existence and not travelling and not eating out, they probably should be seeing somebody”.

| Drug | Mechanism of action | Evidence | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peppermint oil | Anti-spasmodic | Meta-analysis of four small studies comparing peppermint oil with placebo found a number needed to treat to prevent persistent symptoms of 2.5 | Very few side effects |

| Hyoscine | Anti-spasmodic | Meta-analysis of three small studies comparing hyoscine with placebo found a number needed to treat to prevent persistent symptoms of 3.5 | Very few side effects |

| Mebeverine | Anti-spasmodic | No high-quality evidence to suggest efficacy. Some patients report benefit | Very few side effects |

| Loperamide | Anti-diarrhoeal | Four small studies showed stool frequency was reduced and stool consistency improved in patients treated with loperamide compared to placebo, but the treatment did not improve abdominal pain or bloating | To be used prophylactically during a flare-up of diarrhoea. Contraindicated in people with inflammatory bowel disease. |

| Bisacodyl/lactulose | Stimulant/osmotic laxative | Evidence for efficacy mostly in mixed populations with constipation including some people with IBS. In these populations there is some evidence for improvement in bowel habit | To be used for the short-term treatment of constipation. Side effects can mimic symptoms of IBS e.g. cramps, abdominal pain, bloating. |

| Ispaghula husk | Bulk-forming laxative | Limited and conflicting evidence of symptom improvement | To be used for the short-term treatment of constipation. Side effects can mimic symptoms of IBS e.g. cramps, abdominal pain, bloating. |

| Probiotics | Bacterial strains delivered in live or dead cultures to change composition of the microbiome | Some evidence that Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species can have a positive effect on symptoms, but not consistently replicated | Most studies report no adverse events |

When patients do come to the attention of a gastroenterologist, a number of different drugs may be prescribed. “There isn’t a gold standard because each patient has an individual treatment and IBS is a very broad term,” says Spiller. For example, loperamide may be prescribed for those with diarrhoea, says Nick Talley, a neurogastroenterologist at the University of Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia, although he warns that it needs to be taken as prophylactic therapy rather than after each bowel motion. Other drugs that can be co-opted into IBS treatment include osmotic laxatives for constipation and even low doses of the antidepressive amitriptyline, which can reduce pain and bowel motility.

The mainstay of drug treatment for IBS is antispasmodics — smooth muscle relaxants such as mebeverine. “The commonest prescribed drug [for IBS] in the UK is mebeverine,” says Spiller, but he adds that its supporting clinical trial evidence, which was published in the 1980s is unconvincing. From his own clinical practice, Spiller suggests that “maybe one in ten patients think it’s good”.

Source: Courtesy of Robin Spiller

Robin Spiller, a gastroenterologist specialising in irritable bowel syndrome at the University of Nottingham, says it is reasonable for some IBS sufferers to self-manage with over-the-counter treatments

And while none of the evidence for drugs used to treat IBS is great, Spiller says, conducting trials is expensive. Treatments for IBS are “off patent and generic, so why would [drug companies] pay money?” he says.

On the other hand, antispasmodics have very few side effects so doctors are happy to prescribe them. As Cryan points out: “Because [IBS] doesn’t kill you, tolerance for side effects is low.”

Because [IBS] doesn’t kill you, tolerance for side effects is low

Off-prescription

Not all IBS treatments involve a prescription. “My first approach is dietary change and recommending exercise,” says Talley.

Some people benefit from cutting out gluten, others from what is known as the low FODMAP diet. FODMAP stands for ‘fermentable, oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols’, a collection of short chain carbohydrates and sugar alcohols including fructose and lactose. The theory behind the FODMAP diet is that these molecules are bulky and can make it all the way to the large intestine, where they are finally broken down by bacteria. This causes the release of gas and, consequently, colonic distension. The molecules also draw water in after them, which may explain the diarrhoea some IBS sufferers experience. The low FODMAP diet is tough to follow and rules out quite a few fruits and vegetables, but “it can be very helpful for a number of people if they can tolerate [it]”, Talley says.

Reducing stress is another take-home message Talley gives his patients, although, as Chaddock says, this is easier said than done. Some IBS sufferers object to a focus on stress for other reasons, feeling that the public and health professionals dismiss their symptoms as all in their head. Talley is careful to reassure his patients that IBS is “a real gut disease”. IBS is associated with a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression, but it seems that the link between the brain and the gut is very real. As Cryan says, “we use it in our everyday language: ‘gut feeling’, ‘gut instinct’.” And, he continues, it is clear from work with animals that are reared in sterile environments that “to have normal brain development you need to have normal microbes in your gut”. This link between the brain and your bowels may be your microbiome, the particular combination of bacterial species that live in your intestine.

To have normal brain development you need to have normal microbes in your gut

In 2009, Cryan published results from a study in rats that showed early life stress — in this case separation of pups from their mothers — led to IBS-like symptoms, as well as a change in the bugs that were found in their faeces[1]

. In other words, “early life stress can change the microbiome”, says Cryan, and this, he believes “can have knock-on effects on the nervous system”. But does this link translate to humans?

There is some evidence for early life trauma being connected with IBS, and there is also some evidence for changes in the microbiota of IBS patients. However, these changes are not consistent — some studies report an increase in certain species of bug, while others show a decrease. Similarly, some studies have found that probiotics are beneficial, but, “the problem with the probiotic studies is that they’re all very different strains”, says Cryan.

Talley takes a pragmatic approach to probiotics, which he does recommend to his patients but with a caveat. “I tell people it’s a bit of trial and error and encourage them that if after a month they don’t get benefit from one particular type to try something else.” If they find something that works for them, he is happy, although he acknowledges that he isn’t sure whether it’s placebo or not.

The evidence for whether and which probiotics and prebiotics (nutrients that encourage the growth of specific bacteria) might be helpful in IBS may be limited and sometimes contradictory, but there is clear evidence that the non-absorbable antibiotic rifaximin can help some people with IBS[2]

.

“[Rifaximin] presumably alters the microbiome,” says Talley, but adds that some people also think it has an anti-inflammatory effect. “If you respond [to it], then it changes your natural history — you’ll have a more prolonged symptom-free interval than if you took placebo, which no other drug does,” he says. But even though responders will have a symptom-free interval after finishing a course of the medication, all patients seem to relapse. And not everyone responds in the first place.

Research problems

One of the major issues with researching treatments for IBS is that scientists often lump together patients with various underlying problems. This means that a treatment may be benefiting one subgroup of patients but if other subgroups are not seeing an improvement, the value of the intervention might not reach statistical significance. “It looks like IBS will turn out to be tens of diseases or more,” says Talley.

Source: Courtesy of Nick Talley

Nick Talley, a neurogastroenterologist at the University of Newcastle, Australia, and his team are working on nanotechnology that would enable drugs to be delivered locally to the area of the gut affected

Currently, patients are classified as having ‘diarrhoea-predominant IBS’, ‘constipation-predominant IBS’, or ‘mixed IBS’. There is also ‘post-infectious IBS’, which develops in between 5% and 30% of people who experience acute gastroenteritis.

It looks like IBS will turn out to be tens of diseases or more

One option for classifying IBS more accurately might be to subgroup patients using genetic profiling. The genetics of IBS is “in its infancy”, acknowledges Beate Niesler, a geneticist specialising in neurogasteroenterological disorders at Heidelberg University Hospital in Germany, who is one of a small group of researchers working in the field.

“To date, only a few twin and family studies have been published with variable results in terms of genetic contribution,” she says. However, “genes involved in the immune response, gut barrier and neurological function have been consistently replicated”. Niesler has been instrumental in setting up the international interdisciplinary network GENIEUR (the Genes in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Research Network Europe), which aims to nail down the genetics and epigenetics of IBS. The ultimate goal is to be able to subgroup IBS patients according to which pathways are affected, facilitating treatment.

Another option — and an approach that is already yielding benefits — is subgrouping patients according to their microbiome. For example, in 2012, a group of researchers looked at the faecal microbiota composition of 37 patients with IBS[3]

. They found that their sample could be divided into two groups: one group had an increase of Firmicutes -associated taxa and a depletion of Bacteroidetes -related taxa relative to healthy controls; while the second group had a normal-like microbiota composition not very different to that of the controls. Interestingly, this second group was significantly more likely to be depressed, suggesting that the second group could be best treated with psychological interventions and the first with probiotics.

The microbiome has been shown to have value in predicting beneficial treatments. Sean Bennet, who is doing a PhD focused on IBS at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, is part of a team that studied the microbiome of patients who did and did not improve with a low FODMAP diet. They found that there were differences in the faecal microbiota between responders and non-responders. “Being able to discriminate the non-responders means that we can say: ‘Okay, there’s not really any point in you going on this [diet] because it’s a long, arduous intervention’,” says Bennet.

Immunity and inflammation

Results from Cryan’s rat study also showed that rats subjected to early life stress had an increased immune response and were more sensitive to bowel distension than normal controls1. Immunity and inflammation have been implicated in IBS, as has abnormally high sensitivity to stimuli that might go unnoticed in a control population.

Talley says that an infection, post-infectious inflammation or even the composition of your microbiome can lead to what is known as a ‘leaky gut’, meaning that “food and bacteria get presented to the gut immune system and so [people] get an inflammatory response”. That inflammatory response could lead to the release of cytokines from T cells and these could “drive some of the manifestations of IBS, particularly the extra-gut manifestations like anxiety, fatigue and poor sleep”, Talley says.

However, according to Talley, the problem is that this low-grade inflammation doesn’t respond to traditional anti-inflammatory therapies, and dealing with it will require a new approach. His team is working on nanotechnology that would enable drugs to be delivered locally to the area of the gut affected.

As for increased sensitivity, results from a study published in 2016 by Spiller and colleagues showed that IBS patients and normal controls given a drink crammed full of FODMAPs both suffered from colonic distension on MRI, but the IBS patients were more likely to report discomfort[4]

.

“There’s an objective stimulus that they’re responding to but the difference is normal people don’t get symptoms,” says Spiller. He puts this down to a defect in a descending pathway that inhibits painful stimuli that can be switched off or even reversed so that painful stimuli are more appreciated than normal. The gut has its own ‘brain’ — the enteric nervous system — which has a two-way relationship with the central nervous system. It is possible that one of the triggers for this hypersensitivity is stress; another could be an abnormal microbiome.

In an effort to ‘normalise’ the microbiome, some patients are resorting to faecal transplantation, a technique that started out in 4th century China. This involves the transfer of a solution of faecal matter from a healthy donor into the recipient’s intestinal tract. So far there are limited data on the efficacy of faecal transplantation for IBS[5]

, but some desperate sufferers are still willing to give it a go.

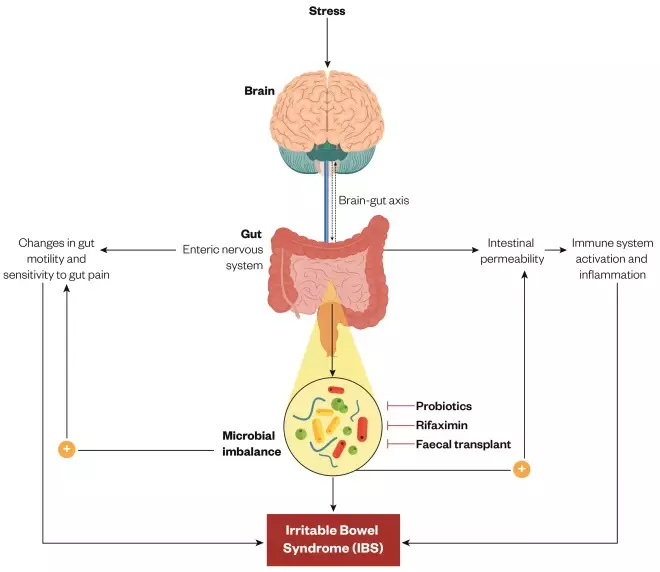

Figure 1: Microbiome: the link between brain and bowels

Source: Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology

The gut-brain axis links emotional and cognitive centres within the brain to peripheral functioning of the gastrointestinal tract, which is controlled by the enteric nervous system. Scientists are looking into the factors that influence this two-way system, including stress, which may be connected to changes in gut motility, an increased sensitivity to pain, and immune system activation and inflammation, all symptoms that characterise irritable bowel syndrome.

IBS in the future

So how bright is the future for IBS patients? Chaddock thinks a cure may take some time. He has found talking to other sufferers through UK-based charity The IBS Network helpful, and now runs his own support group in Leeds. “Talking about bowels is still a bit of an embarrassing subject, so being able to go into a room with other people who have had similar experiences is great,” he says.

Cryan also thinks we have some way to go: “We need to do more basic science and get more interest from pharmaceutical companies,” he says. But he is hopeful that, as more research is done, it will yield exciting new treatments. After all, as he says: “The difference between the microbiome and your genome is that you can change your microbiome.”

References

[1] O’Mahony SM, Marchesi JR, Scully P et al. Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biol Psychiatry 2009;65:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.026

[2] Saadi M & McCallum RW. Rifaximin in irritable bowel syndrome: rationale, evidence and clinical use. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease 2013:4:71–75. doi: 10.1177/2040622312472008

[3] Jeffery IB, O’Toole PW, Öhman L et al. An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut 2012;61:997–1006. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301501

[4] Major G, Pritchard S, Murray K et al. Colon hypersensitivity to distension, rather than excessive gas production, produces carbohydrate-related symptoms in individuals with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2017;152:124–133. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.062

[5] Gupta S, Allen-Vercoe E & Petrof EO. Fecal microbiota transplantation: in perspective. Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology 2015;9:229–239. doi: 10.1177/1756283X15607414