View the full infographic here

1953

- Pharmacist and pharmacologist Stewart Adams (pictured) and chemist John Nicholson, employed at Boots Pure Drug Company Ltd, begin work to identify an analogue of aspirin that might be suitable for long-term use for rheumatoid arthritis

Source: Boots UK

1961

- After screening more than 600 candidates, Adams and Nicholson file a patent for the compound 2-(4-isobutylphenyl) propionic acid, later to be called ibuprofen; it is granted the following year

1966

- Clinical trials of ibuprofen take place in Edinburgh in six patients with rheumatoid arthritis

1969

- Ibuprofen is launched in the UK for treatment of rheumatic diseases and marketed as prescription medicine Brufen at a dose of 600–800mg per day

- Ibuprofen compares favourably with gold standard treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, aspirin, but with a better gastrointestinal side-effect profile[1]

Early 1970s

- Brufen tablets are granted a product licence of right by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) following the introduction of a licensing system in 1971

Source: Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

1979

- Additional indications for ibuprofen are added to the datasheet in the UK, including non-articular rheumatic conditions, periarticular conditions and soft tissue injuries

1981

- Mild to moderate pain is added as an indication for ibuprofen in the UK

1983

- Ibuprofen is approved as an over-the-counter (OTC) medicine in the UK at a maximum daily dose of 1,200mg and launched as Nurofen

1985

- Boots worldwide patent for ibuprofen expires and generic products are launched

- Boots receives the Queen’s Award for Technological Achievement for discovering ibuprofen, and by this time more than 100 million people in 120 countries have received ibuprofen

1995

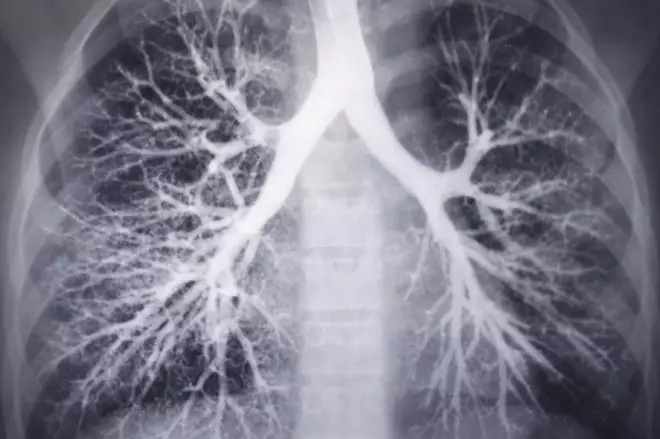

- A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial reveals that high doses of ibuprofen (mean dose 25mg/kg) slow lung disease in patients with cystic fibrosis by inhibiting release of lysosomal enzymes and the migration, adherence, swelling and aggregation of neutrophils[2]

Source: Shutterstock.com

1996

- Ibuprofen is switched to general sale list (GSL) status, meaning it can be sold in general retail outlets without the supervision of a pharmacist

2005

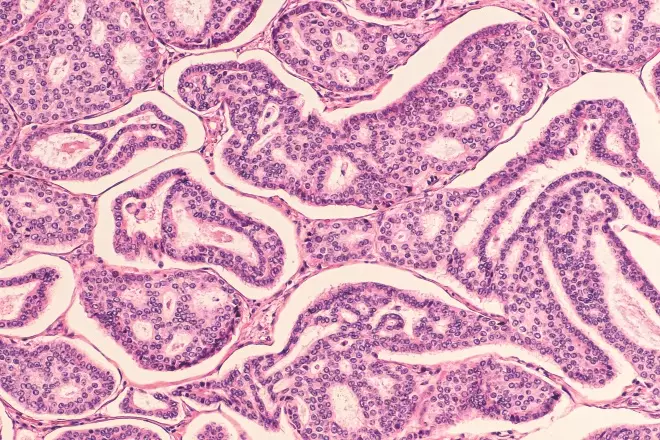

- An observational study involving 114,000 women suggests that long-term (>5 years) daily use of ibuprofen is associated with a 51% higher risk of breast cancer[3]

. Information on dose was not collected

Source: Shutterstock.com

- An epidemiological study suggests that regular use of ibuprofen lowers the risk of Parkinson’s disease (PD)[4]

. A Cochrane review in 2011 also shows that ibuprofen may reduce the risk of PD but says many questions remain before its potential use[5]

2006

- Following a review of new thrombotic cardiovascular safety data, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) concludes that non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be associated with a small increase in the absolute risk for thrombotic events, especially when used at high doses (>2,400mg for ibuprofen) for long-term treatment. However, the overall benefit–risk balance remains favourable

2008

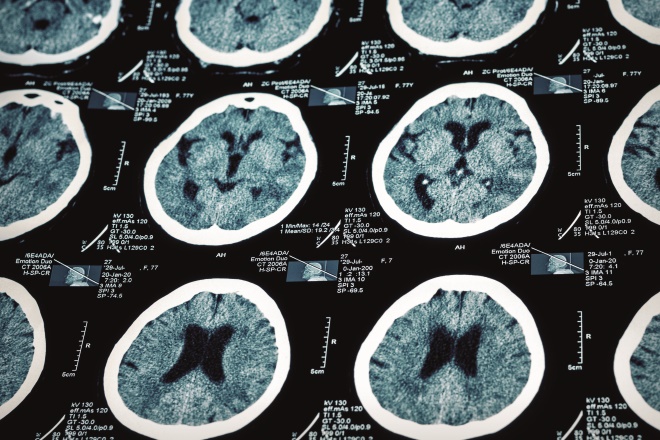

- An observational study suggests that use of ibuprofen for more than 5 years is associated with a 44% reduction in risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease[6]

Source: Shutterstock.com

2014

- A systematic review finds that fast-acting formulations of ibuprofen demonstrate more rapid absorption, faster initial pain reduction, good overall analgesia in more patients at the same dose, and probably longer-lasting analgesia, but with no higher rate of patients reporting adverse events[7]

- The MHRA asks the EMA (pictured) to review the safety of ibuprofen. The following year, the EMA confirms that high doses (>2,400mg per day) of ibuprofen carry a small increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, such as heart attack and stroke. No increase is seen at OTC doses (up to 1,200mg)

Source: Shutterstock.com

2016

- The advertising watchdog bans a UK TV advertisement for Nurofen because it falsely claims that the product can specifically target joint and back pain. Nurofen products marketed for specific types of pain were removed from sale in Australia in 2015 because they misled consumers

- In laboratory and animal studies, researchers at Imperial College London find that ibuprofen arginine (not licensed in the UK but available elsewhere) could protect from adverse cardiovascular effects by preserving the nitric oxide pathway, as well as being released into the bloodstream more quickly than standard ibuprofen[8]

- Current use of ibuprofen or other NSAIDs is linked to a 19% increased risk of hospital admission for heart failure, an observational study of more than 8 million NSAID users in four countries, finds[9]

. The authors say that although the study focused only on prescription NSAIDs, the findings might apply to NSAIDs obtained over the counter as well - Based on prescription data, ibuprofen is linked to a 31% increase in risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in an observational study of nearly 30,000 patients. No information on OTC use was available[10]

2017

- An observational study suggests that taking ibuprofen (and other NSAIDs) during a cold or flu infection increases risk of heart attack by 3.3 times for high dose and 3 times for low-dose preparations[11]

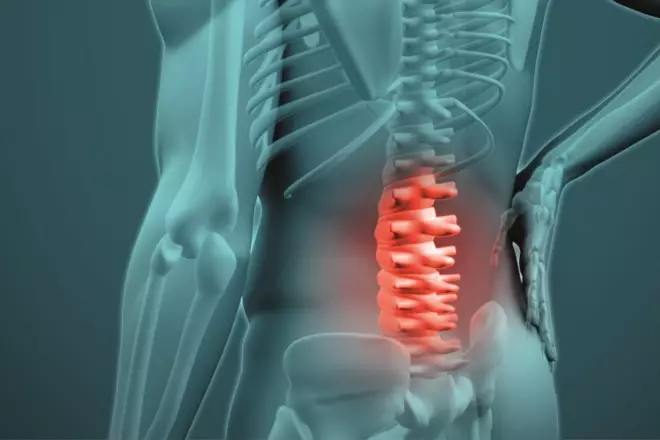

- A systematic review finds that ibuprofen and other NSAIDs do not provide clinically important effects for back pain over placebo[12]

Source: Shutterstock.com

- Ibuprofen at doses >1,200mg daily, along with other NSAIDs, increases risk of myocardial infarction, especially within the first month, according to an analysis of data from nearly 450,000 patients[13]

References

Sources: Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA); European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Editorial advisers: Roger Knaggs, associate professor in clinical pharmacy practice, University of Nottingham; Emily Rose-Parfitt, rheumatology specialist pharmacist, North Bristol NHS Trust.

[1] Chalmers TM. Clinical experience with ibuprofen in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1969;28:513. PMCID: PMC1031238

[2] Konstan M, Byard P, Hoppel C et al. Effect of high-dose ibuprofen in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 1995;332:848–854. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503303321303

[3] Marshall SF, Bernstein L, Anton-Culver H et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and breast cancer risk by stage and hormone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:805–812. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji140

[4] Chen H, Jacobs E, Schwarzschild M et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use and the risk for Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 2005;58:963–967. doi: 10.1002/ana.20682

[5] Rees K, Stowe R, Patel S et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as disease-modifying agents for Parkinson’s disease: evidence from observational studies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;Nov 9;(11):CD008454. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008454.pub2

[6] Vlad SC, Miller DR, Kowall NW et al. Protective effects of NSAIDs on the development of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2008;70:1672–1677. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000311269.57716.63

[7] Moore RA, Derry S, Straube S et al. Faster, higher, stronger? Evidence for formulation and efficacy for ibuprofen in acute pain. Pain 2014;155:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.08.013

[8] Kirkby NS, Tesfai A, Ahmetaj-Shala B et al. Ibuprofen arginate retains eNOS substrate activity and reverses endothelial dysfunction: implications for the COX-2/ADMA axis. FASEB J 2016;30:4172–4179. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600647R

[9] Arfè A, Scotti L, Varas-Lorenzo C et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of heart failure in four European countries: nested case-control study. BMJ 2016;354:i4857. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4857

[10] Sondergaard K, Weeke P, Wissenberg M et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use is associated with increased risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a nationwide case-time-control study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2017;356:100–107. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvw041

[11] Wen YC, Hsiao FY, Chan KA et al. Acute Respiratory Infection and Use of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs on Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Nationwide Case-Crossover Study. J Infect Dis 2017;215:503–509. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw603

[12] Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for spinal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1269–1278. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210597

[13] Bally M, Dendukuri N, Rich B et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction with NSAIDs in real world use: bayesian meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMJ 2017;357:j1909. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1909