Burger / Phanie / Science Photo Library

Drug allergy, as defined by the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology, is an adverse drug reaction with an established immunological mechanism[1]

. All forms of natural and semisynthetic penicillins or drugs with a similar structure, such as cephalosporins or carbapenems, can cause allergy. These drugs, which have a beta-lactam ring, are recognised as one of the most frequent causes of immediate (within 1 hour) and delayed (after 72 hours) drug reactions.

Correct diagnosis can be difficult, but true allergy is more likely if the patient has recognised allergic symptoms (e.g. rash, rash involving hives, wheezing, or swelling of the skin or throat), or has previously experienced a similar reaction to the same agent or another agent in the same class. Gastrointestinal symptoms alone do not represent a true allergy and alternative biological or pharmacological explanation should be excluded before a diagnosis of allergy is made[2]

.

Adverse reactions to penicillin have been reported in 0.2–5.0% of individuals per course of treatment[3]

. However, fewer than 10% of those believed to be allergic to penicillin are truly allergic[2]

. As a result, antibiotics can be withheld unnecessarily, affecting clinical outcomes, increasing healthcare costs and potentially contributing to the development of drug-resistant bacteria[3]

. Accurate diagnosis and antimicrobial stewardship practices are therefore key[2]

.

Delabelling — the removal of inappropriate patient allergy labels — allows first-line treatment options to be used. These are often more effective antibiotics with fewer side effects, have a narrower spectrum of activity and are more cost efficient[4]

. Using effective narrow-spectrum agents where possible is one of the major aims of antimicrobial stewardship and ensures the right drug is being used for the right patient. Current practice of delabelling allergy status in the UK varies and may depend on whether there is an established local allergy service or whether pharmacists have the capacity to assess patients’ allergies on admission to hospital.

Pharmacists, working as part of the wider multidisciplinary team, are able to effectively manage infections in patients with antibiotic allergies by delabelling their inappropriate allergy status on admission[5]

(see Box 1). The process of optimising medication on admission to hospital currently falls under the remit of doctors and pharmacists[6]

.

This article describes the possible consequences of labelling a patient with an antibiotic allergy; the subsequent impact on patient outcomes; how pharmacists can undertake appropriate investigations and delabel patients; and when to refer patients to specialist allergy services. This article complements a previous article on the identification and management of penicillin allergy[3]

.

Mechanisms of action and prevalence

Beta-lactams

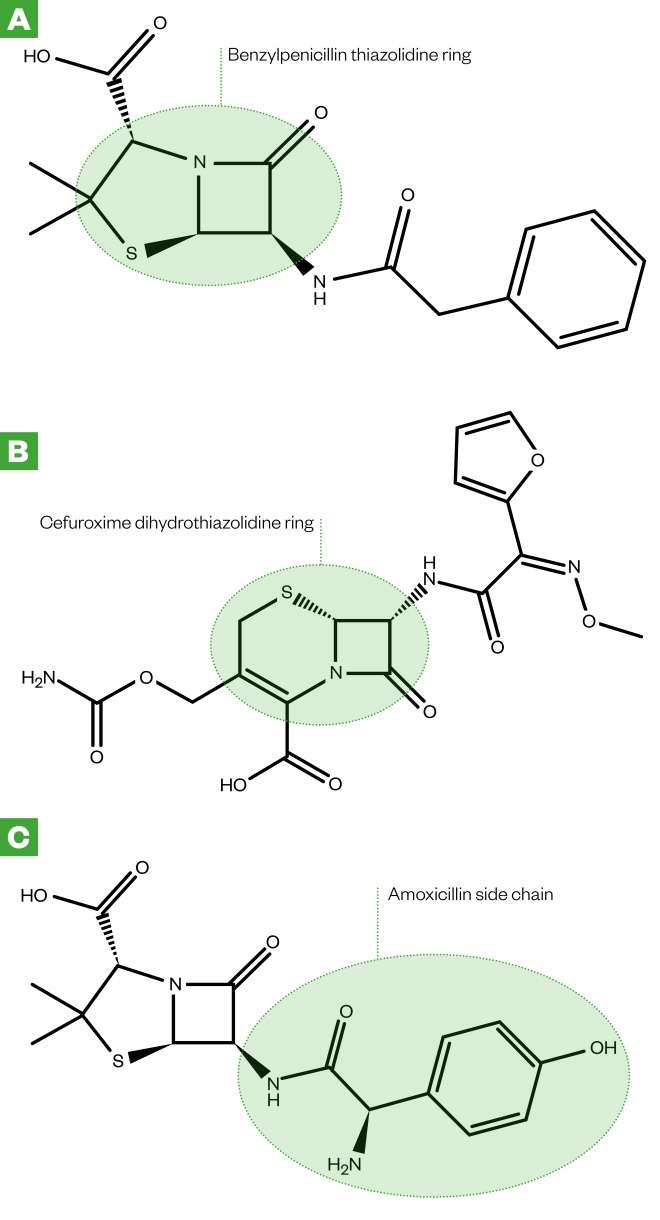

Allergic reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics can be attributed to their drug chemistry and metabolism. The beta-lactam ring (thiazolidine ring in penicillins and dihydrothiazine ring in cephalosporins) and the side chains are immunogenic (see Figure 1). Drug metabolites containing these components act as haptens (incomplete antigens) that can covalently bind to larger proteins to elicit an immune response, resulting in the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies[7]

.

Once administered, benzylpenicillin will spontaneously undergo degradation to form reactive intermediate products, such as benzylpenicilloyl, the major antigenic determinant to which most patients with allergies react. This metabolite binds to proteins and is used in commercially available skin testing kits in the UK. The remaining penicillin metabolites can also act as haptens (called minor determinants) and account for around 16% of allergic reactions[7]

. Beta-lactam allergy has been identified as a possible independent risk factor for other classes of antibiotic allergy[8]

.

Figure 1: Chemical structures of benzylpenicillin (A), cefotaxime (B) and amoxicillin (C)

[7]

The thiazolidine ring in penicillins, the dihydrothiazine ring in cephalosporins and the side chains in beta-lactam antibiotics are immunogenic. Drug metabolites containing these components act as incomplete antigens that can covalently bind to larger proteins to elicit an immune response in patients.

Non-beta-lactams

Allergic reactions to non-beta-lactam antibiotics occur less frequently and IgE-mediated anaphylaxis is rare[9]

.

Anaphylaxis to fluoroquinolones is reported to occur with an incidence of 1.8–2.3 per 10 million treatment days and accounts for 4.5% of all drug-induced anaphylaxis[8],[10]

. Moxifloxicin is associated with more severe allergic reactions than ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin[10]

. Up to 70% of allergies reported with moxifloxacin are immediate hypersensitivity reactions[8]

; it is restricted for use by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency owing to an association with non-allergic, life-threatening hepatic reactions[11]

. Ciprofloxacin is most commonly associated with delayed skin reactions[8]

.

Sulphonamide allergy rates are reported at around 2% and anaphylaxis is rare, but patients with HIV/AIDS have an increased risk of a reaction[10]

. They are associated with more severe life-threatening reactions, such as drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), which typically appear between two and ten weeks after initiation[10]

.

Vancomycin is associated with the pseudo-allergy ‘red man syndrome’ (RMS), an IgE-independent histamine reaction with a worldwide incidence rate of 3.7–47%. Slowing infusion rates to 500mg/hour greatly reduces the risk of RMS. Anaphylaxis is possible but rare, and DRESS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis have also been observed. Anaphylaxis to teicoplanin has been reported at an incidence of 1 in around 1,600 perioperative patients[12]

.

Macrolide IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions are drug-specific, not class-specific, and are uncommon, occuring in 0.4–3% of patients treated[10]

. Allergic reactions to tetracyclines are rare, although more common with minocycline. They are associated with anaphylaxis and life-threatening skin reactions (e.g. DRESS)[10]

. Drug-induced lupus has been reported with minocycline and may appear two to six years after initiation[13]

.

Aminoglycoside allergic reactions are extremely rare, although case reports of anaphylaxis and contact dermatitis have been reported with topical preparations[10]

.

Perioperative anaphylaxis

The recent National Audit Project on perioperative anaphylaxis declared that antibiotics were the main cause of anaphylaxis in the perioperative period in the UK, accounting for 46% of reported cases with an identified causal agent[12]

. The authors found the incidence of antibiotic anaphylaxis to be 4 per 100,000 administrations, with teicoplanin, co-amoxiclav and vancomycin being the most prevalent. The most common clinical feature of antibiotic anaphylaxis was hypotension, occurring in 42% of cases, and the onset of anaphylaxis was within 5 minutes in 74% of cases, within 10 minutes in 92% of cases, and in all cases anaphylaxis occurred within 30 minutes after drug exposure[12]

.

Disappearance of allergies

Avoidance of the drug that initially triggered anaphylaxis results in reduced IgE antibody concentrations that can disappear completely over time[14]

. Around 80% of patients with a true allergy to penicillin, confirmed with skin testing and who avoided penicillin after diagnosis, were subsequently found to have a negative skin test after 10 years[15]

. Resensitisation to penicillin is possible following re-exposure, but rates are very low, with levels similar to patients with no previous allergy[16]

. However, patients with severe delayed allergic reactions (e.g. Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis and DRESS) should not receive the causative agent again, as the risk of these reactions recurring does not decrease over time[14],[15]

.

Penicillin allergy labels

Penicillin-based antibiotics are often used as first-line treatment for infections. Therefore, patients previously diagnosed as allergic to penicillin, whose notes are marked with ‘penicillin allergy’ labels, are usually prescribed non-penicillin agents that are often more costly, more toxic and may be less effective. See the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s (NICE) Clinical Guideline 183 for more information on its identification and management[2]

.

Source: Dr P Marazzi / Science Photo Library

An allergic reaction to the antibiotic penicillin can result in a rash

Use of broad-spectrum penicillin alternatives in incorrectly labelled patients increases the risk of future infections with resistant bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus and Clostridioides difficile (formerly known as Clostridium difficile)[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23]

. In addition, patients are exposed to a greater number of antibiotics, including quinolone and carbapenem agents, further contributing to selection pressures for resistance[17],[23],[24]

.

Incorrectly labelled patients may also be denied appropriate treatment with newer beta-lactam derivatives unnecessarily. The joint Infectious Diseases Society of America and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guideline on antimicrobial stewardship recommends the promotion of allergy assessment and testing, where appropriate, owing to the potential impact this could have on the utilisation of first-line agents[25]

.

An email survey of 55 UK hospitals revealed there to be little evidence that hospitals are tackling the issue of incorrect penicillin allergy labelling[26]

. This may be owing to the lack of allergy services available, meaning patients with incorrect penicillin allergy labels cannot be completely reviewed and confirmed by allergy services alone. However, many low-risk patients (e.g. those who only experience gastrointestinal symptoms or give a history of non-severe delayed skin reactions) can be safely delabelled without the need for skin allergy testing[27],[28]

.

Pharmacists working with a multidisciplinary team to undertake allergy assessments, as outlined in Box 1, have been shown to reduce non-beta-lactam consumption and increase beta-lactam first-line therapy[23],[29]

. There is a role for ward-based pharmacy technicians to contribute to this process during the medication reconciliation process.

Primary care pharmacists can ensure documentation of allergy status is as detailed as possible and highlight inappropriate allergy labelling to GPs. Community pharmacists can ensure patients understand the difference between true allergy and intolerance when discussing allergy status, as well as directing patients for update or assessment of allergy status.

Delabelling ‘penicillin allergic’ patients

Although delabelling programmes with pharmacist involvement have been successfully delivered in US hospitals, the introduction of penicillin allergy delabelling programmes is a complex intervention that requires changes in the behaviour of both healthcare professionals and patients[23],[30],[31]

. Healthcare professionals need to feel confident using decision tools to delabel those incorrectly labelled as penicillin allergic and the process of delabelling needs to be supported by NHS management[32]

. Fear of patient harm through lack of understanding around which allergy labels are inappropriate may prevent healthcare professionals delabelling inappropriate allergy status in patients[32]

. Delabelled patients and parents of delabelled children need to trust the test and the advice that they are given and that it is safe to take penicillin in the future if deemed non-allergic. Patients and healthcare professionals may still avoid penicillin, even after the delabelling has taken place, if they are not confident in the delabelling process[33]

. Many patients retain their allergy status in their medical notes despite a negative oral challenge test[34]

.

Implementing a sustainable penicillin allergy delabelling service in NHS hospitals will require understanding and expertise regarding the influences on behaviour and human factors. A guide on how to achieve delabelling in the hospital setting is provided in Box 1.

This approach to penicillin allergy clarification and delabelling, without the use of skin allergy testing, is reported to delabel between 16% and 50% of patients, enabling the use of first-line penicillin therapy[19],[23],[29],[35],[36],[37],[38]

.

The two case studies (see Panel 1) illustrate the approaches to managing penicillin allergy clarification and delabelling, and when skin allergy testing would be required.

Box 1: Step-by-step guide to determine the significance of reported antibiotic allergies[2]

- Step 1: Obtain a thorough systematic clinical history and patient clinical examination

The information gathered will help to determine if the reaction occurred immediately after administration, or if it was a delayed reaction with or without systemic involvement. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence provides a comprehensive list of questions that can be used to assess a patient’s history; these questions can be found in the previous penicillin allergy article[3]

.

-

Step 2: Scrutinise previous medical records including GP records

-

Step 3: Delabel patients with non-specific (non-immunological) reactions

Those who have tolerated the index penicillin antibiotic since the initial episode, or who have a clear history of side effects or intolerance allergy tests, are not required and allergy label can be removed without allergy testing.

-

Step 4:

Refer to allergy services

Skin testing is required for patients with an uncertain history or a history in keeping with an immunologic aetiology (see Box 2).

Panel 1: Case studies

Case study 1

A 28-year-old female with a history of anxiety recalls a childhood history of rash associated with oral penicillin therapy when she was under the age of 5 years. She cannot recall what she was being treated for at the time; however, she does recall her mother telling her that she had a red rash all over her body. No treatment was required and the rash went away over a couple of days. She has subsequently tolerated cephalexin therapy. Her listed allergy is to penicillin.

This patient gives a history of a non-severe delayed skin reaction more than ten years ago; therefore, her risk of allergy on re-exposure to penicillin is low. She subsequently underwent direct oral rechallenge with penicillin VK 250mg without prior skin testing and without adverse event. She has tolerated penicillin post-challenge.

Case study 2

A 74-year-old female with multiple medical comorbidities reports a history of allergy to amoxicillin from one year previous. She developed lip tingling, dizziness, nausea and central chest pain five minutes after the ingestion of oral amoxicillin, which was being used to treat a dental infection. She called for an ambulance; however, on their arrival was noted to have a very low blood pressure (60/20mmHg) and full-body erythema, which they treated with two intramuscular injections into her thigh. She was transferred to hospital and stayed in the intensive care unit for 24 hours before being discharged home. Her listed allergy is to amoxicillin.

This patient describes an immediate-onset severe reaction, likely secondary to amoxicillin. Skin testing is required to determine her allergy status. She was skin-tested using a standard panel with an isolated positive intradermal skin test to ampicillin. She tolerated penicillin VK and cefuroxime orally post-testing. She has continued to avoid amoxicillin, ampicillin, cephalexin and cefaclor owing to the shared side chain.

Referral to specialist allergy services

NICE recommends that patients should be referred to allergy specialists, where available, if they have a possible allergy to beta-lactams and are likely to need antibacterial therapy in the future; for example, patients with recurrent infections (e.g. urinary tract infections or cystic fibrosis), patients at increased risk of recurrent infections (e.g. bronchiectasis), or patients generally at an increased risk of infection (e.g. if they have asplenia [absence of normal spleen function] or other immunodeficiencies) (see Box 2)[2]

.

Box 2: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommendations for patients requiring referral to specialist allergy centres

[2]

Patients should be referred to specialist allergy clinics if they have had:

- A suspected anaphylactic reaction to a drug;

- A severe delayed cutaneous reaction;

- A suspected allergy to beta-lactam antibiotics and will require, or are likely to require, treatment with beta-lactams in the future;

- A suspected allergic reaction to a beta-lactam antibiotic and at least one other class of antibiotics.

At time of writing, there are 33 allergy centres across the UK providing allergy services for adults, with 3 centres in Scotland, and 1 each in Wales and Northern Ireland[12]

.

Available tests

Skin-prick testing, intradermal testing, and oral and intravenous drug challenges can be used for patients requiring further allergy testing. These tests are critical where the history describes serious allergic reactions; risk assessments based on historical descriptions alone are not reliable.

Skin-prick testing involves using a panel of reagents. For penicillin testing, this includes major and minor determinants, amoxicillin and benzylpenicillin, plus amoxicillin/clavulanic acid if this was the offending drug. Other agents can also be used depending on the drug in question[7]

.

Testing should take place in a specialist allergy centre to ensure correct interpretation of results and management of the patient if a severe reaction occurs. These tests should be undertaken relatively quickly after the initial reaction, as positive test results are less likely to be determined as the time period increases[39]

. Standard practice in the UK is to wait six weeks after the initial allergic reaction took place to test for allergies. However, there is little evidence to support this and testing may be carried out earlier if required. Early negative test results may lead to the patient being retested at a later date[7]

.

Positive results

Histamine is used as a positive control (weal size can be used as a comparison) and sodium chloride acts as a negative control[7]

. A weal diameter of a least 3mm greater than the negative control is considered a positive result. Flare and itch also supports a positive result[7]

. Based on the history of the initial reaction, patients are observed for 15–20 minutes for an immediate response and up to 72 hours for delayed responses[28]

.

Patients who test positive to the oral challenge may need to undergo desensitisation if alternative antibiotics cannot be used or when a specific drug is necessary for treatment[7]

.

If any of the results to the tests described are positive, the patient, GP and relevant referring clinician should be informed of the outcome to ensure consistent documentation (see Box 3). NICE also make recommendations about patient information and support (see Box 4).

Box 3: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommendations on the documentation of new drug reactions and allergies

[2]

Use the following structured format when documenting new drug reactions. Note:

- The generic and proprietary drug name;

- The route of administration;

- The date and time of the reaction;

- The indication for the drug;

- The number of doses/days drug taken before reaction occurred;

- Whether the drug, or others, may need to be avoided in the future.

Box 4: Patient information and support by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

[2]

Patients who are found to be diagnosed with drug allergies at specialist allergy centres should be provided with the following information:

- The diagnosis and whether it was an allergic or non-allergic drug reaction;

- The name of the drug and an explanation of the reaction;

- The investigations and tests used;

- The type of drugs the patient will need to avoid in the future.

Negative results

Negative skin-prick and intradermal test results mean that the patient can receive a graded oral challenge to confirm they can tolerate the antibiotic. Oral testing is not required for patients with positive skin tests and is not recommended for patients that have had previous delayed severe cutaneous reactions, have severe asthma or are taking beta-blockers[40]

. Beta-blockers may be temporarily withheld for up to 48 hours, based on the decision of the GP or cardiologist.

A negative skin-prick result would indicate that intradermal testing should be undertaken. Results are assessed at different intervals, usually at 20 minutes, 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours[7]

.

If intradermal skin tests are negative, the patient and clinician can decide whether oral and intravenous drug challenges are suitable. An example of an oral penicillin provocation test includes 25mg, 100mg, 500mg and 1g doses of amoxicillin given at 30-minute intervals, with standard patient observations (i.e. pulse, blood pressure, oxygen saturations and peak expiratory flow rate) at baseline, before the next dose and 1hour after the final dose[7],[40]

. If the oral and intravenous tests are uneventful, a full treatment course of the antibiotic (usually five days) is given as per local guidelines and the patient is contacted at the end of the course to establish clinical tolerance. A thorough management plan with emergency treatment should be provided in case of allergic reactions that occur at home[7]

.

The role of pharmacy professionals

Pharmacists should be able to clarify the nature of an allergy, the significance of reactions to antibiotics and determine whether these and other class-related antibiotics need to be avoided in future. Pharmacists can ensure clear documentation of allergy status and community pharmacists in particular should be able to discuss allergies and the difference between allergy and intolerance with patients; for example, before they purchase over-the-counter medication or when they are dispensing prescriptions for antibiotics[2]

. Although often considered the remit of the GP, pharmacists can also offer advice on which patients should be referred to specialist allergy clinics.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jason Trubiano, infectious diseases physician and director of antimicrobial stewardship and drug and antibiotic allergy services at Austin Health, University of Melbourne, Australia, for providing the case studies included in this article.

References

[1] Mirakian R, Ewan PW, Durham SR et al. BSACI guidelines for the management of drug allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39(1):43–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03155.x

[2] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Drug allergy: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG183]. 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg183 (accessed July 2018)

[3] Jethwa S. Penicillin allergy: identification and management. Pharm J 2015;295(7878):185–187. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2015.20069170

[4] Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. Penicillin allergy — getting the label right. Drug Ther Bull 2017;55(3):33–36. doi: 10.1136/dtb.2017.3.0463

[5] Doron S & Davidson LE. Antimicrobial stewardship. Mayo Clin Proc 2011;86(11):1113–1123. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0358

[6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. NICE guideline [NG5]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5 (accessed July 2018)

[7] Mirakian R, Leech SC, Krishna MT et al. Management of allergy to penicillins and other beta-lactams. Clin Exp Allergy 2015;45(2):300–327. doi: 10.1111/cea.12468

[8] Doña I, Moreno E, Pérez-Sánchez Net al. Update on quinolone allergy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2017;17(8):56. doi: 10.1007/s11882-017-0725-y

[9] Warrington R & Silviu-Dan F. Drug allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2011;7(Suppl 1):S1–S10. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-7-S1-S10

[10] Sánchez-Borges M, Thong B, Blanca M et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to non beta-lactam antimicrobial agents, a statement of the WAO special committee on drug allergy. World Allergy Organ J 2013;6(84). doi: 10.1186/1939-4551-6-18

[11] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Moxifloxacin: increased risk of life-threatening liver reactions and other serious risks. 2011. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/moxifloxacin-increased-risk-of-life-threatening-liver-reactions-and-other-serious-risks (accessed July 2018)

[12] Harper N, Cook TM & Garcez T. Anaesthesia, surgery, and life-threatening allergic reactions: epidemiology and clinical features of perioperative anaphylaxis in the 6th National Audit Project (NAP6). Br J Anaesth 2018;121(1):159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.04.014

[13] Shapiro LE, Knowles SR & Shear NH. Comparative Safety of tetracycline, minocycline, and doxycycline. Arch Dermatol 1997;133(10):1224–1230. PMID: 9382560

[14] Trubiano JA, Adkinson NF & Phillips EJ. Penicillin allergy is not necessarily forever. JAMA 2017;318(17):1714–1715. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13763

[15] Chen JR, Tarver SA, Alvarez KS et al. A proactive approach to penicillin allergy testing in hospitalized patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5(3):686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.045

[16] Solensky R, Earl HS & Gruchalla RS. Lack of penicillin resensitization in patients with a history of penicillin allergy after receiving repeated penicillin courses. Arch Intern Med 2002;162(7):822–826. PMID: 11926858

[17] Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Varughese CA et al. Impact of a clinical guideline for prescribing antibiotics to inpatients reporting penicillin or cephalosporin allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015;115(4):294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.05.011

[18] Borch JE, Andersen KE & Bindslev-Jensen C. The prevalence of suspected and challenge-verified penicillin allergy in a university hospital population. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2006;98(4):357–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_230.x

[19] Li M, Krishna MT, Razaq S & Pillay D. A real-time prospective evaluation of clinical pharmaco-economic impact of diagnostic label of ‘penicillin allergy’ in a UK teaching hospital. J Clin Pathol 2014;67(12):1088–1092. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202438

[20] Wood CA & Wisniewski RM. Beta-lactams versus glycopeptides in treatment of subcutaneous abscesses infected with Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1994;38(5):1023–1026. PMID: PMC188144

[21] Blumenthal KG, Shenoy ES, Huang M et al. The impact of reporting a prior penicillin allergy on the treatment of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. PLoS One 2016;11(7):e0159406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159406

[22] Charneski L, Deshpande G & Smith SW. Impact of an antimicrobial allergy label in the medical record on clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy 2011;31(8):742–747. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.8.742

[23] Sigona NS, Steele JM & Miller CD. Impact of a pharmacist-driven beta-lactam allergy interview on inpatient antimicrobial therapy: A pilot project. J Am Pharm Assoc 2016;56(6): 665–669. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2016.05.005

[24] Al-Hasan MN, Acker EC, Kohn JE et al. Impact of penicillin allergy on empirical carbapenem use in Gram-negative bloodstream infections: an antimicrobial stewardship opportunity. Pharmacotherapy 2018;38(1):42–50. doi: 10.1002/phar.2054

[25] Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Aboo LM et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62(10):e51–e77. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw118

[26] Powell, N. Impact of penicillin allergy labels, a hospital survey. [unpublished data] 2017

[27] Confino-Cohen R, Rosman Y, Meir-Shafrir K et al. Oral challenge without skin testing safely excludes clinically significant delayed-onset penicillin hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5(3):669–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.02.023

[28] Krishna MT, Huissoon AP, Li M et al. Enhancing antibiotic stewardship by tackling “spurious” penicillin allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2017;47(11):1362–1373. doi: 10.1111/cea.13044

[29] Park MA, McClimon BJ, Fergusin B et al. Collaboration between allergists and pharmacists increases beta-lactam antibiotic prescriptions in patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2011;154(1):57–62. doi: 10.1159/000319209

[30] Leis JA, Palmay L, Ho G et al. Point-of-care beta-lactam allergy skin testing by antimicrobial stewardship programs: a pragmatic multicenter prospective evaluation. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65(7):1059–1065. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix512

[31] Blumenthal KG, Wickner PG, Hurwitz S et al. Tackling inpatient penicillin allergies: assessing tools for antimicrobial stewardship. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;140(1):154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.02.005

[32] Wilcock M, Powell N & Sandoe J. A UK hospital survey to explore healthcare professional views and attitudes to patients incorrectly labelled as penicillin allergic: an antibiotic stewardship patient safety project. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2018; epub. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2017-001451

[33] Vyles D, Chiu A, Routes J et al. Antibiotic use after removal of penicillin allergy label. Pediatrics 2018. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2018/04/18/peds.2017-3466 (accessed July 2018)

[34] Lachover-Roth I, Sharon S, Rosman Y et al. Long-term follow-up after penicillin allergy delabeling in ambulatory patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018; In print. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.04.042

[35] Knezevic B, Sprigg D, Seet J et al. The revolving door: antibiotic allergy labelling in a tertiary care centre. Intern Med J 2016;46(11):1276–1283. doi: 10.1111/imj.13223

[36] Trubiano JA, Cairns KA, Evans JA et al. The prevalence and impact of antimicrobial allergies and adverse drug reactions at an Australian tertiary centre. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:572. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1303-3

[37] Preston SL, Briceland LL & Lesar TS. Accuracy of penicillin allergy reporting. Am J Hosp Pharm 1994;51(1):79–84. PMID: 8135263

[38] Trubiano J & Phillips E. Antimicrobial stewardship’s new weapon? A review of antibiotic allergy and pathways to ‘delabeling’. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2013;26(6):526–537. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000006

[39] Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. Penicillin allergy — getting the label right. BMJ 2017;358:j3402. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3402

[40] Royal College of Physicians. Improving quality in allergy services. 2018. Available at: https://www.iqas.org.uk (accessed July 2018)

You might also be interested in…

UK Clinical Pharmacy Association launches pharmacogenomics guidance

Health news round-up: cardiovascular disease, women’s health and the potential for new sepsis treatment