Alfred Pasieka / Science Photo Library

In this article you will learn:

- The key risk factors for the development of gout

- How to manage acute gout attacks

- When gout prophylaxis should be considered

- Lifestyle advice you should offer patients with gout

Gout is a common type of inflammatory arthritis that causes severe pain, discomfort and damage to joints. It is estimated to affect 1.4% of the UK population and worldwide prevalence is rising — particularly in high income countries[1]

.

It is caused by the deposition of monosodium urate crystals — which are formed from excess uric acid — in joints and soft tissue. Uric acid is formed from the breakdown of purine nucleotides from internal or ingested sources.

The deposition of crystals may continue for months or years without causing symptoms and it is only when the crystals are shed into the bursa (small sacs of synovial fluid that surround the joint) that an inflammatory reaction occurs. The shedding of crystals can be triggered by a number of factors including direct trauma, dehydration, rapid weight loss, illness and surgery.

Timely and effective treatment of gout is necessary to reduce the risk of flares, chronic polyarthritis and tophaceous disease. Tophaceous disease occurs when crystals build up under the skin, forming white or yellow lumps (tophi), which can cause permanent damage to the joints.

Although prolonged hyperuricaemia can lead to the development of gout, not all patients with raised serum uric acid levels develop the condition.

Risk factors

Excess uric acid is normally excreted by the body through the kidneys. However, if this function is impaired or if there is an increased purine intake, hyperuricaemia can occur. Overproduction of uric acid — increased purine burden — is the cause for gout in less than 10% of patients. Therefore, reduced excretion of uric acid by the kidneys is believed to be the cause of hyperuricaemia in most cases of gout.

The kidney excretes about two thirds of the uric acid that is produced by the body, the remainder is eliminated via the billiary tract. Loop and thiazide diuretics cause volume depletion and reduced tubular renal secretion of uric acid and are commonly associated with the development of gout. A number of other medicines are also associated with increased uric acid levels (see ‘Medicines that can raise uric acid levels’).

Medicines that can raise uric acid levels

- Aspirin

- Ciclosporin

- Cytotoxic medicines

- Diuretics (loop and thiazide)

- Ethambutol

- Levodopa

- Pyrazinamide

- Ribavarin and interferon

- Teriparatide

Some patients may have a genetic predisposition to gout. Approximately 90% of uric acid that passes through the kidneys is reabsorbed. This process is mediated by specific anion transporters — such as URAT-1 — located on the renal proximal tubule. Although common primary gout in men often shows a strong familial predisposition, the genetic basis for this is not fully understood. However, a polymorphism of the SLC22A12 gene, which encodes URAT-1, has been associated with under excretion of uric acid[2]

[3]

.

Other independent risk factors include obesity, weight gain, hypertension and dyslipidaemia (hypertriglyceridaemia is present in up to 25% of patients with gout)[4]

.

Alcohol consumption has also been associated with a greater risk of developing gout. The metabolism of ethanol to acetyl coezyme A leads to the breakdown of the purine nucleotide adenine and the production of uric acid. Alcohol also raises lactic acid levels in blood, inhibiting uric acid excretion. Some alcoholic beverages also contain high levels of purine (e.g., beer).

Gout is more common in men and prevalence rises with age. Some 7% of men aged 75 years to 84 years are affected, compared with 4% of women aged over 75 years[5]

. Gout tends to develop in women after menopause, when oestrogen levels fall. Oestrogen increases the excretion of uric acid; therefore, when oestrogen levels fall, uric acid levels may rise.

Diagnosis method

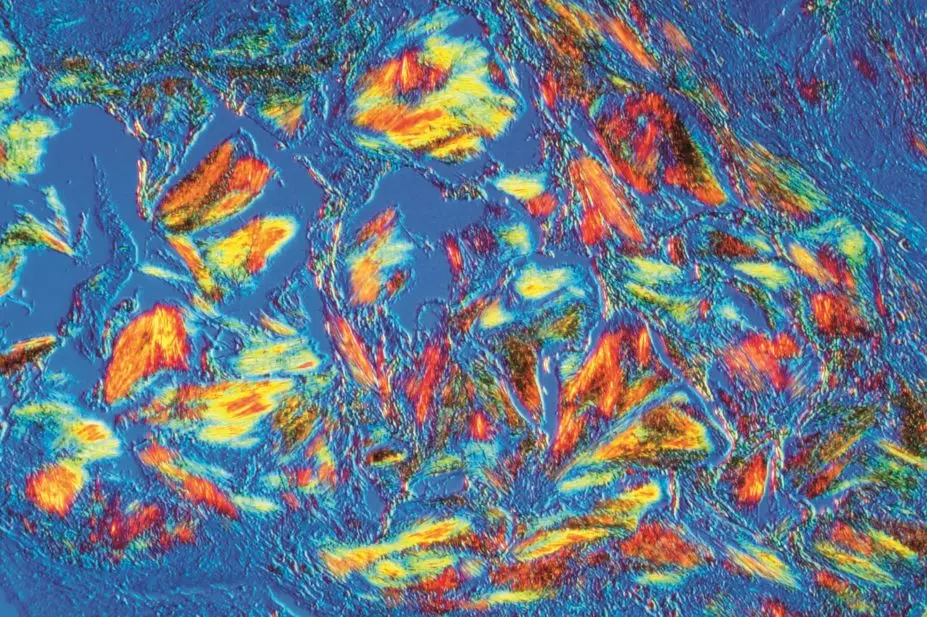

Polarised light microscopy is considered the gold standard method for diagnosing gout. Fluid is drawn from the joint and examined. The crystals are 10–20µm long and needle-shaped, and produce a strong, intense, characteristic light pattern under polarised light. Crystals may also be found in fluid aspirated from non-inflamed joints.

Serum uric acid levels are measured during an acute attack to aid diagnosis. However, during an acute attack of gout a third of patients may have a normal uric acid plasma concentration. During the acute inflammatory phase, there is increased urinary urate excretion causing a lowering of the uric acid concentration in the plasma. A repeat level should be taken two to three weeks after the attack has resolved to give a true reflection of the actual plasma level.

Synovial fluid samples should be sent to microbiology to exclude septic arthritis.

Cases of acute gout

Source: reprinted with the permission of Philip Conaghan

In severe cases of gout, crystals can build up under the skin, forming white or yellow lumps called tophi

In most cases, the first acute gout attack affects a single joint in the lower limbs, most commonly the first metatarsophalangeal joint (the big toe). This is sometimes referred to as podagra (seizing the foot). Subsequent attacks may be polyarticular (involve multiple joints) and other commonly affected areas include the mid-foot, ankle, knee, wrist and finger joint. Onset of acute gout is rapid, but some patients may experience prodromal symptoms, such as loss of appetite, nausea or changes in mood.

The most common symptom of acute gout is pain, which is most severe between 6 hours and 24 hours of onset. Affected joints are hot, red and swollen and have shiny overlying skin. Patients may also have a fever, leukocytosis and raised inflammatory markers.

An acute attack of gout will resolve spontaneously within several days or weeks and can leave some patients with pruritis and desquamation of the overlying skin on the affected joint.

Patients should be advised to rest the joint and use an ice-pack to reduce inflammation. Medicines used in the management of an acute flare-up of gout include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), colchicine and corticosteroids. The aim of treatment is to relieve pain rapidly.

NSAIDs should be used as a first-line treatment for the management of an acute attack. They should be started immediately at high doses, which are then tapered 24 hours after complete resolution of the attack. Continual use of NSAIDs should be avoided. At present there is no convincing evidence that any one NSAID licensed to treat gout is more effective than others in acute management.

Colchicine is used as an alternative for patients who are contraindicated to NSAIDs. Although the exact mode of action of colchicine is poorly understood, it is believed to arrest the assembly of microtubules in neutrophils and inhibit many cellular functions.

There is a slower onset of action when using colchicine (six hours compared with around two hours for NSAIDs); therefore it should be started as soon as possible after the onset of an attack.

The recommended dose for an acute attack of gout is 500µg of colchicine two to four times a day. Common side effects include abdominal cramps, nausea and vomiting. Rarely, bone marrow suppression, neuropathy and myopathy can also occur.

Adverse effects are more common in patients with hepatic or renal impairment. The dose of colchicine should be reduced in mild-to-moderate renal impairment (i.e., creatinine clearance [CrCl] 10–50ml/min). The Renal Drug Handbook suggests reducing the frequency of dose to two to three times a day. However, in clinical practice, doses rarely exceed 500µg twice a day. Colchicine should not be used for patients with severe renal impairment (i.e., CrCl<10ml/min). Colchicine should also be used with caution in patients with chronic heart failure because it can constrict blood vessels and stimulate central vasomotor centres, worsening symptoms.

Colchicine is metabolised by the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP3A4 and excreted by P-glycoprotein. Increased serum drug levels and toxicity can occur when colchicine is prescribed concomitantly with some medicines, including macrolides, ciclosporin and protease inhibitors. The absorption of vitamin B12 may be impaired by chronic administration of high doses of colchicine.

Corticosteroids are used to treat acute gout when NSAIDs and colchicine are contraindicated or not effective. They may be given orally, intramuscularly or by intra-articular injection.

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections are highly effective in treating acute gout for patients with only one affected joint. Common doses of intra-articular corticosteroids include methylprednisolone acetate 80mg for large joints, such as a knee, and methylprednisolone acetate 40mg or triamcinolone acetonide 40mg for smaller joints, such as a wrist or elbow.

Oral corticosteroid regimens include prednisolone 30mg daily for one to three days, with subsequent dose tapering over one to two weeks. Corticosteroids may cause fewer adverse events than other acute treatments when used short term, particularly in the elderly.

Prophylaxis of gout

For some patients, following lifestyle alterations (see ‘Lifestyle advice’) and adjusting medication regimens can prevent subsequent attacks. However, if patients have one or more acute attacks within 12 months of an initial attack, uric acid-lowering therapy is needed to prevent further flare-ups. It may be appropriate to start prophylaxis after the first attack for certain patient groups, such as:

- Patients with visible gouty tophi

- Patients with renal insufficiency (glomerular filtration rate <80ml/min)

- Patients with uric acid stones

- Patients who need to continue diuretics

To avoid prolonging an attack of gout, treatment with prophylactic uric acid lowering therapies should not be started until two to three weeks after an attack has completely resolved. When prophylactic treatment is started, there is a risk of precipitating a flare due to a shift in the plasma uric acid concentration as a consequence of increased uric acid excretion. To prevent a flare, either an NSAID or colchicine is co-prescribed when prophylactic treatment is initiated.

The recommended dose of colchicine for prevention of acute gout is 500µg twice a day for up to six months. NSAIDs may be prescribed for a period of up to six weeks if colchicine is contraindicated. Intramuscular corticosteroid injections (methylprednisolone acetate 80–120mg) or oral corticosteroids are also sometimes used to prevent the precipitation of flares during the initiation of prophylactic therapy.

If an acute attack occurs, patients should continue prophylactic uric acid-lowering therapy.

The aim of prophylactic treatment for gout is to maintain serum uric acid levels below the saturation point of monosodium urate; if serum urate is maintained below this level, crystal deposits dissolve. The British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) recommends maintaining plasma urate below 300 µmol/L to prevent further attacks5, whereas European guidance proposes levels less than 360 µmol/L[6]

[7]

. Uric acid levels and renal function should be measured at least every three months for the first year5. Measurements should then continue on an annual basis.

Allopurinol is the medicine of choice for prophylaxis in the management of recurrent gout. It inhibits the action of the enzyme xanthine oxidase, thus reducing the production of uric acid. For patients with normal renal function, the starting dose is 100mg daily, increased gradually in 100mg increments every two to three weeks until the optimal serum urate level (<300µmol/L) or the maximum dose (900mg per day in divided doses) is reached. Allopurinol and its metabolite oxypurinol are excreted by the kidneys and it is essential that the dose is appropriately reduced for patients with inadequate renal function (refer to appropriate literature for more details).

A decrease in serum urate should occur within a couple of days of starting allopurinol, with a peak effect at seven to ten days. The dissolution of tophi may take up to 12 months.

Around 3% to 5% of patients treated with allopurinol experience an adverse reaction to the medicine, usually a hypersensitivity reaction within the first two months of treatment. Adverse effects reported with allopurinol include rash, fever, worsening renal failure, hepatotoxicity, vasculitis and death.

Severe toxicity occurs in less than 2% of patients. The risk of toxicity increases with renal impairment, age and concurrent drug therapy (e.g., diuretics).

Allopurinol interacts with a number of medicines, including azathioprine and mercaptopurine — which are metabolised by xanthine oxidase. The dose of azathioprine or mercaptopurine should be reduced to around a quarter of the normal dose when co-prescribed with allopurinol, and full blood counts should be performed at regular intervals to identify potential toxicity. High doses of allopurinol (i.e., more than 600mg daily) increase carbamazepine blood levels by around one-third.

Febuxostat is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for patients with chronic hyperuricaemia who are intolerant of allopurinol or for whom allopurinol is contraindicated[8]

. Febuxostat is a more selective and potent inhibitor of xanthine oxidase than allopurinol, and has no effect on other enzymes involved in purine or pyrimidine metabolism. It is licensed for the treatment of chronic hyperuricaemia for conditions where urate deposition has already occurred, including a history or presence of a tophus, gouty arthritis, or both.

The recommended starting dose for febuxostat is 80mg once daily. Febuxostat has a faster onset of action than allopurinol and serum uric acid levels can be tested two weeks after starting therapy. If the serum uric acid is greater than 357 µmol/L after two to four weeks, the dose should be increased to 120mg once daily.

The dose of febuxostat does not need to be adjusted for patients with mild or moderate renal therapy, but there are no current recommendations for patients with severe renal impairment (CrCl ≤ 30ml/min). For patients with mild hepatic impairment, the dose should not exceed 80mg daily. The use of febuxostat has not been studied in patients with severe hepatic impairment. Febuxostat should not be given to patients with ischaemic heart disease or congestive heart failure because of the risk of cardiovascular adverse effects.

The most common adverse effects of febuxostat are respiratory infection, nausea, diarrhoea, headache and liver function abnormalities. Liver function should be tested in all patients before therapy is started, and periodically thereafter based on clinical judgement. Febuxostat is not recommended for patients taking mercaptopurine or azathioprine.

Uricosuric medicines that increase excretion of uric acid, have traditionally been used to manage gout. Examples include sulphinpyrazone and probenecid. Probenecid is no longer marketed in the UK and is less effective than the other medicines as monotherapy. Uricosuric medicines should only be prescribed for patients with adequate renal function and fluid intake. They should not be given to patients with pre-existing renal stones.

Benzbromarone, another uricosuric medicine, is no longer licensed in the UK and was withdrawn from the market because of its potential to cause hepatoxicity. It is available on a named-patient basis for patients with normal liver function who are intolerant of other prophylactic uric acid-lowering medicines.

Pegloticase was used in the past for more extreme cases of gout with significant tophi. This medicine is no longer available.

Anakinra and canakinumab are biologic agents that may have a role in the management of severe, refractory tophaceous gout[9]

. The medicines target interleukin-1, which is associated with the inflammatory response induced by monosodium urate crystals. Canakinumab is administered by subcutaneous injection and is licensed for frequent gouty arthritis attacks where other agents are ineffective or there is intolerance. Anakinra is not licensed for the treatment of gout.

Advice on lifestyle changes

Lifestyle modification can be effective in preventing further gout attacks. Moderate physical exercise can be beneficial, but intense muscular exercise should be avoided because it can lead to a rise in uric acid levels.

Overweight patients should lose weight gradually, as rapid weight loss can precipitate ketosis and a subsequent rise in urate levels.

Patients should ensure their purine intake does not exceed 200mg per day. However, it is the regular consumption of foods containing purines, rather than the absolute purine content of a particular food, that is important. See ‘Purines in food — what to eat and what to avoid’.

| High purine foods (avoid) | Moderate purine foods (eat in moderation) | Low purine foods (eat normally) |

|---|---|---|

Offal – liver and kidneys, heart and sweetbreads Game – pheasant, rabbit, venison Oily fish – anchovies, herring, mackerel, sardines, sprats, whitebait, trout Seafood – especially mussels, crab, shellfish, fish, roe, caviar Meat and yeast extracts – Marmite, Bovril, commercial gravy, beer Source: The UK Gout Society | Meat/poultry – beef, lamb, pork, chicken, duck Mushrooms and mycoprotein (Quorn) Dried peas, beans and legumes – baked beans, kidney beans, soya beans, peas Some vegetables – asparagus, cauliflower, spinach Wholegrains – bran, oatbran, wholemeal bread

| Dairy – milk, cheese, yoghurt, butter Eggs Bread and cereals (except wholegrain) Pasta and noodles Fruit and vegetables (see moderate purine foods for exceptions)

|

Foods such as shellfish, offal and sardines should be avoided, and the intake of soft drinks sweetened with fructose or sucrose should be limited

[10]

.

It is recommended that men restrict their alcohol consumption to less than 21 units per week and men and women have at least three alcohol-free days per week. Beer, stout, port and fortified wines should be avoided.

Dairy products are beneficial in lowering serum uric acid and eating yoghurt on alternate days can help reduce levels[11]

. Cherries are high in vitamin C and can also help increase uric acid excretion[12]

.

This article was amended on 5 September to clarify that the statement “at present there is no convincing evidence that any one NSAID is more effective than others for the management of acute gout” refers to NSAIDs licensed for this indication.

Tina Hawkins, IPRESC, MRPharmS, is advanced clinical pharmacist for rheumatology at Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust

References

[1] Smith E, Hoy D, Cross M et al. The global burden of gout: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1470–1476.

[2] Graessler J, Graessler A Unger S et al. Association of the human urate transporter-1 with reduced renal uric acid excretion in a German caucasian population. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2006;54:292–300.

[3] Taniguchi A, Urano W, Yamanaka M et al. A common mutation in an organic anion transporter gene SLC22A12 is a suppressing factor for the development of gout. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2005;52:2576–2577.

[4] Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW et al. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Archives Internal Medicine 2005;165:742–748.

[5] Jordan KM, Cameron S, Snaith M et al. British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1372-1374. Available from: doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kem056b [Accessed 11 August 2014].

[6] Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part I: Diagnosis. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65: 1301–1311. Available from: doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.055251 [Accessed 11 August 2014].

[7] Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1312–1324. Available from: doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.055269. [Accessed 11 August 2014].

[8] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Febuxostat for the management of hyperuricaemia in people with gout. December 2008 [Online]. Available from: www.guidance.nice.org.uk/ta164 [Accessed 4 August 2014].

[9] Cavagna L, Taylor WJ. The emerging role of biotechnological drugs in the treatment of gout. Biomed Research International [Online] 2014. Available from: doi:10.1155/2014/264859 [Accessed 11 August 2014].

[10] Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW et al. Purine rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. NEJM 2004;350:1093–1103.

[11] Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW et al. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Archives Internal Medicine 2005;165:742–748.

[12] Huang HY, Appel LJ, Choi MJ et al. The effects of vitamin C supplementation on serum concentrations of uric acid: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2005;52:1843–1847.