Alex Baker

As accessible frontline healthcare professionals, community pharmacists manage patients with common conditions and support healthy living alongside dispensing medicines and providing support with medication use. In addition to providing information, advice and education, this expanded role may include supporting behaviour change and referral to other healthcare professionals or signposting to other community or support services[1,2].

Peripheral joint pain is a frequent presentation in community pharmacy, and can be defined as mechanical pain of any joint (excluding the spine), with or without loss of function. In patients aged 45 years and over, mechanical joint pain is often caused by osteoarthritis (OA)[3], and is frequently associated with co-existing physical and mental health problemsand reduced quality of life[4–6]. The impact of mechanical joint pain on daily activities varies between individuals and also depends on the joint affected. For example, stairs can be problematic for those with knee or hip pain, while thumb pain can impact grip. In addition to joint abnormality, person-specific central factors (e.g. anxiety, depression, catastrophising trait, non-restorative sleep) can modify pain experience and the degree of participation restriction.

Although OA is the most common musculoskeletal condition causing mechanical joint pain, other potentially serious causes of joint or bone pain include gout, other inflammatory arthritides, infection, fractures, malignancy, and radicular or neuropathic pain[3]. Prolonged morning joint-related stiffness (more than 30 minutes), hot swollen joints, rapid worsening of symptoms, systemic upset and a history of trauma or cancer are ‘red flags’ which raise suspicion of a more serious underlying cause, and are indications for a prompt medical review.

Core treatments

In those aged 45 years and older presenting to community pharmacy with joint pain and no features suggesting an alternative diagnosis, it is appropriate to apply the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) OA guideline treatment recommendations[3].

Core treatments recommended by NICE for the treatment of joint pain are non-pharmacological, can be provided in the pharmacy setting and are recommended for all patients, regardless of their age, comorbidity, pain or disability[3]. Some are outlined in the following sections and resources to support delivery of these treatments are provided in ‘Signposting to local services and trusted online resources’.

Patient information

People presenting with mechanical joint pain should be provided with clear and accurate verbal and written information to help them understand the nature of their condition, its causes and possible consequences, and its treatment options. Individualisation of this information and discussion of illness perceptions is recommended.

Exercise

Advise patients to maintain, rather than avoid, movement through sensible “pacing” of activities and to carry out both aerobic and strengthening exercises. Aerobic exercise can reduce pain and improve function, well-being and sleep quality. Local strengthening exercises also improve pain and function, and can reverse some of the negative impacts of knee joint pain, such as reduced muscle strength, proprioception and balance, and increased tendency to fall.

The effect of exercise on pain and function, if undertaken regularly over three months, is safe, and may reduce requirement for analgesia[6–8]. There are very few absolute contraindications to exercise, for example acute fever or infection, certain cardiac conditions (e.g. obstructive cardiomyopathy or severe valve disease, myocarditis or arrhythmias [particularly if uncontrolled or exercise induced]) and other unstable conditions (e.g. angina, diabetes or hypertension). If such problems are suspected or if there is uncertainty about the safety of, or approach to, advising exercise in the presence of another health problem, the patient should be referred to their GP or a specialist for advice.

Any exercise is better than none at all. Patients can undertake adequate exercise without any special equipment. Helping patients to build exercise into their daily routine can equip them to make changes straight away. For example, walking when travelling short distances rather than using transport. Linking exercise to a daily activity can also be helpful, for example, undertaking ten minutes of aerobic activity before having their morning shower, doing strengthening exercises while waiting for the kettle to boil (or the tea to brew), or making the exercise part of daily activity, such as planning to do ten minutes of gardening every day.

Weight management

Weight loss should be supported for overweight or obese patients. Advice for patients could include suggesting that they eat breakfast every day, to be mindful of intake of calories contained within drinks, eat slowly to enable the body to recognise when it is full and monitor their weight once per week.

In addition to providing verbal advice, pharmacists can signpost to online NHS advice and local weight loss services, including dietitians. Where appropriate, pharmacists can discuss pharmacological (e.g. orlistat) or surgical approaches[9].

Weight loss has beneficial effects on both pain and function associated with chronic joint pain[10]. People may be more likely to maintain weight loss if they combine diet with regular exercise.

Appropriate footwear

Pharmacists can give advice on appropriate footwear. Patients’ footwear should have thick but soft soles, no raised heel, broad forefoot and deep soft uppers.

Adjunctive treatments

Many of the additional treatments recommended by NICE which have a positive impact on pain and/or function are available over the counter (OTC).

Non-pharmacological first-line strategies include supports and braces and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation machines. Thermotherapy (i.e. use of heat or ice as a therapeutic intervention) can also be effective[3].

Pharmacological treatments are adjunctive and purely for pain relief. First-line pharmacological treatment for most joints (except deep joints, such as shoulders or hips), is use of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)[3]. For patients with hand and knee pain, topical NSAIDs may be just as effective as oral NSAIDs and, apart from occasional local skin reactions, are extremely safe[6]. Similarly, topical capsaicin can be used as an alternative topical treatment for knee and hand pain (see Box for instructions for topical drug application). Second-line pharmacological treatments are oral medications: NSAIDs, paracetamol and the OTC opioid, co-codamol (8mg/500mg)[3]. These medicines should only be considered if first-line options are not appropriate or effective, and if the potential benefit outweighs the risks for the individual patient. Recent evidence on the risks and benefits of paracetamol suggest it is not as safe as previously thought, and has a very low effect size for pain relief in OA; as such, placed paracetamol is second-line rather than first-line therapy[3]. Naturally, before recommending any pharmacological treatments, it is important to be fully aware of the patient’s current medication use (including all prescribed and OTC medicines), other medical conditions (e.g. kidney disease or asthma if considering oral NSAIDs) and important lifestyle factors (e.g. occupation and driving status if considering opioids) that may affect their individual risk profile. OA guidelines from NICE also recommend that all patients taking oral NSAIDs take a gastroprotective agent, specifically a proton pump inhibitor, to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Other OTC treatments, including glucosamine and rubefacients, are not recommended by NICE.

Implementing best practice recommendations

Patients with joint pain may be visiting community pharmacies but may not specifically seek help for their joint pain. Opportunities for pharmacists to proactively support patients with joint pain may arise through existing activities, for example when dispensing prescribed medicines, including with patients who are prescribed regular analgesia[11]. It is important to establish whether patients have tried core treatments and are aware of the risks of their existing medicines[6], whether the risks outweigh the benefits, and to suggest adjuncts or alternatives.

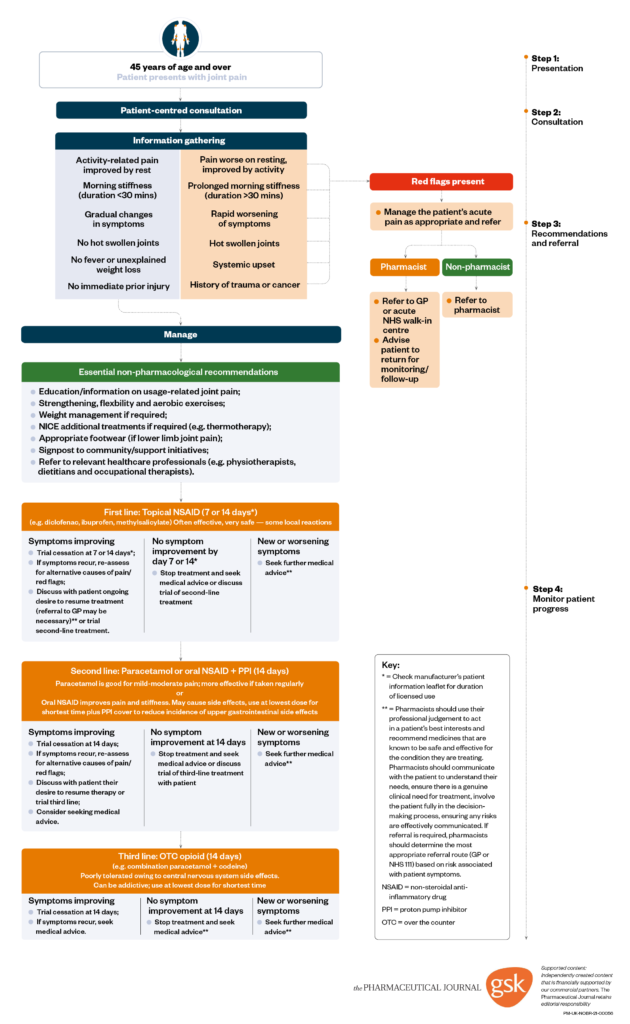

Affected patients may seek help directly about a previously diagnosed joint pain or consult a pharmacist. In either case, it is important to exclude any red flags and not to assume that the patient has already received evidence-based recommendations. It is recognised that advice provided by primary care health professionals and physiotherapists may not entirely align with evidence-based recommendations[12–17]. Furthermore, even if patients have received evidence-based advice before, experience suggests that patients seem to better trust advice if they hear it from different sources. The flowchart (see Figure) provides a useful overview for community pharmacy teams to help patients with joint pain according to their needs.

The above recommendations assume no contraindications to therapy or no drug interactions exist. In such instances, refer patient to the appropriate healthcare professional.MUR: medicines use review; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OTC: over-the-counter; PPI: proton pump inhibitor Source: The Pharmaceutical Journal

When advising patients on both the core and adjunctive treatments for peripheral joint pain, in order to tailor advice to the individual it is important to establish the patients’ priorities, preferences for treatment and previous experience[2]. Often, patients with joint pain seek help or pursue action owing to the associated pain and functional limitations. For example, difficulties when walking the dog, playing with their grandchildren or doing the gardening. Pharmacists should seek to employ the evidence-based recommendations as practical solutions to the patient’s specific problems, for example, using heat (e.g. hot baths or heat packs) for muscle pain/aches and ice (e.g. frozen peas wrapped in damp dish cloth or cold packs) after exercise or in the presence of swelling. Be clear that it may be necessary to experiment to find out what works best for each individual patient[18].

While NICE does not recommend treatments such as acupuncture, glucosamine or herbal treatments (e.g. rosehip and turmeric capsules), some patients perceive benefit from these approaches. Negotiating the benefits, harms (including costs and potentially unregulated strength and purity[3]) and alternatives are, therefore, important. For example, if a patient wants to take glucosamine and the potential harms are perceived as low, focusing on encouraging the addition of exercise into their daily routine, rather than persuading them to stop something they have good faith in, may be appropriate. However, discussions must be balanced and evidence based. The full NICE guidelines provide the research evidence to inform such discussions[3].

Referral

Pharmacists are part of the community multidisciplinary healthcare team. In addition to providing expert advice about the safe use of medicines, as a first point of contact, pharmacists can opportunistically detect potentially problematic joint pain and refer for timely medical review, appropriate exercise (e.g. physiotherapists) and/or weight loss specialists (e.g. dietitians) and, where appropriate, refer to podiatrists for assistance with lower limb joint pain problems.

Signposting to local services and trusted online resources

Community pharmacies should signpost patients with joint pain to local community/support groups[2], for example, walking and/or weight loss groups. A local directory or notice board of relevant services could be developed in collaboration with customers and local organisations. Creation of Health and Wellbeing boards[19]

have resulted in the development of community health initiatives (e.g. Shropshire Together[20]) in which health, council and third-sector organisations come together to support the health and well-being of the community through, for example, weight-loss initiatives and mental health support.

It is important to use clear, professionally presented and evidence-based resources[2]. High-quality resources that can be easily and freely accessed online include:

- Versus Arthritis’s (previously known as Arthritis Research UK) ‘Keep moving’ leaflet, which provides a wealth of information to support patients to exercise, including a poster (in the hard copy) outlining joint strengthening and a range of movement exercises[21];

- Versus Arthritis’s (previously known as Arthritis Research UK) ‘Protecting your joints’ leaflet, which provides advice about ways to approach tasks and movements to protect joints, reduce pain and improve function[22];

- Keele University’s Osteoarthritis Guidebook[18], which includes experiences written by patients for patients and solutions for pain and problems related to joint pain;

- Versus Arthritis’s Osteoarthritis booklet, which provides an overview of the condition from what it is, how it presents and how it can be managed[23];

- The NHS Healthy Weight webpage, which provides interactive tools for assessing weight and links to healthy eating and living advice[24].

Case study

As Mrs Blake, a 64-year-old woman, collects her husband’s large bag of medicines, she sighs: “Here we go again, after struggling home with this again my hands will be good for nothing for the next couple of hours.” You ask what she means. “My hands have been getting very uncomfortable over the past few months, mainly this thumb and the ends of these fingers, carrying the shopping and this lot is so difficult.” You ask about red flags and decide Mrs Blake has got typical hand osteoarthritis. After discussion, you agree that she will read the ‘Protecting your joints’ leaflet, try some exercises outlined in the ‘Keep moving’ leaflet, and she bought some NSAID gel.

The following month, she thanks you for your help; the gel has improved her pain, so she has started using it on her knee as well. Mrs Blake reported feeling low, with everything she has to contend with, her pains are just an extra problem. Not getting out as much and comfort eating had caused her weight to go up. She says: “I feel dreadful.” After discussion, you agree she will see a GP to discuss her mood and will start doing the knee exercises in the ‘Keep moving’ leaflet she already has. You suggest that she takes paracetamol half an hour before exercising and uses ice afterwards if the pain flares. You show her a poster about a local walking group, which may provide her with some support and companionship, as well as helping her to do exercise and lose some weight. You ask her to update you on her progress next month.

Examples of pharmacy support taken from research and implementation projects

Enhanced pharmacy review

Within the Treatment Options for Pain in the Knee (TOPIK) trial, a community pharmacist was supported to optimise patients’ pain control using predefined questions, an analgesic algorithm and a patient information leaflet[25,26]. Patients’ medications were stepped up according to the patients’ response/symptoms using three to six reviews over ten weeks. On average, one hour was spent with patients over three sessions. At three months, significant improvement in patients’ pain scores were noted and at six months, NSAID use had reduced.

Supporting self-management

An international implementation project (JIGSAW-E[27]) used four main healthcare service interventions previously tested in a research study (MOSAICS[28–31]) to support the self-management of patients with OA. The original research was developed for use in the general practice setting, with GPs making the original diagnosis and practice nurses undertaking follow-up appointments. The interventions were: use of the Keele University OA guidebook; an electronic template to prompt and support recording of high-quality management; a model consultation; and professional’s training. These approaches were successfully adapted for use in community pharmacies, which were equipped with hard copies of the OA guidebook and Versus Arthritis exercise leaflets[21], supported by the flowchart in the Figure.

Summary

Joint pain is common in patients aged 45 years and over, and is often caused by OA. These patients may visit community pharmacy frequently but may or may not specifically seek help for their joint pain. Community pharmacy teams and pharmacists can, through appropriate consultation and information gathering, make recommendations based on best practice tailored to the patient’s preferences.

Signposting to community support initiatives is key as part of initial recommendations, given the importance of exercise on pain and function. As accessible healthcare professionals, community pharmacists and their teams are ideally placed to monitor patient progress and update recommendations based on whether symptoms improve, persist or worsen, referring the patient to other healthcare professionals where appropriate.

Box: How to apply topical joint pain treatments

It is important to explain to patients that topical joint pain treatments do not have full effect on first application, and that for both agents recommended within the NICE guidelines (NSAIDs and capsaicin) they can take up to two weeks to give maximum effect.

- Gently massage the cream in using the amount specified on the information leaflet. The action of massaging can have some therapeutic benefit;

- Apply the cream regularly;

- It is quite normal for capsaicin creams to burn on first application, but with regular application the analgesic action takes effect after a few days;

- Do not touch sensitive areas, such as eyes and genitals, after applying capsaicin;

- Try alternatives if you do not like a particular agent because each one is different in terms of stickiness and odour.

Stop using immediately if you get any side effects (e.g. rash) and seek advice.

Acknowledgements

This paper describes independent research (MOSAICS) funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (Grant Reference Number: RP-PG-0407-10386) and an implementation project (JIGSAW-E) funded by EiT Health. Elizabeth Cottrell is an NIHR clinical lecturer in primary care. Johny Quicke is an NIHR academic clinical lecturer in physiotherapy. Krysia Dziedzic is part funded by the NIHR collaborations for leadership in applied research and care West Midlands and by a knowledge mobilisation research fellowship (KMRF-2014-03-002) from the NIHR. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. No fee was sought or offered from any party in respect of this article. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

- 1The Department of Health. Pharmacy in England. Building on strengths — delivering the future. The Stationary Office 2008. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228858/7341.pdf (accessed Apr 2021).

- 2Community pharmacies: promoting health and wellbeing. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng102 (accessed Jan 2019).

- 3Osteoarthritis: Care and management in adults. . National Clinical Guideline Centre, London 2015.

- 4Musculoskeletal conditions and multi morbidity. Versus arthritis. https://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/policy-and-public-affairs/policy-reports/multimorbidity.aspx (accessed Feb 2019).

- 5State of musculoskeletal health 2018: Arthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions in numbers. Versus arthritis. https://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/arthritis-information/data-and-statistics/state-of-musculoskeletal-health.aspx (accessed Feb 2019).

- 6Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2010;18:476–99. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.013

- 7McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2014;22:363–88. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003

- 8Quicke JG, Foster NE, Thomas MJ, et al. Is long-term physical activity safe for older adults with knee pain?: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2015;23:1445–56. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2015.05.002

- 9Obesity: identification, assessment and management. Clinical guideline [CG189]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg189/chapter/1-recommendations (accessed Feb 2019).

- 10Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, et al. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2006;66:433–9. doi:10.1136/ard.2006.065904

- 11Medicines adherence: involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. Clinical guideline [CG76]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2009.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg76/chapter/1-guidance (accessed Jan 2019).

- 12Porcheret M, Jordan K, Jinks C, et al. Primary care treatment of knee pain a survey in older adults. Rheumatology 2007;46:1694–700. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kem232

- 13Holden MA, Nicholls EE, Hay EM, et al. Physical Therapists’ Use of Therapeutic Exercise for Patients With Clinical Knee Osteoarthritis in the United Kingdom: In Line With Current Recommendations? Physical Therapy 2008;88:1109–21. doi:10.2522/ptj.20080077

- 14Cottrell E, Roddy E, Foster NE. The attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of GPs regarding exercise for chronic knee pain: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-11-4

- 15Cottrell E, Foster NE, Porcheret M, et al. GPs’ attitudes, beliefs and behaviours regarding exercise for chronic knee pain: a questionnaire survey. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014999. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014999

- 16Holden MA, Whittle R, Waterfield J, et al. O20. HOW DO PHYSIOTHERAPISTS APPROACH ANALGESIC USE IN PATIENTS WITH HIP OSTEOARTHRITIS? FINDINGS FROM A MIXED METHODS STUDY. Rheumatology 2017;56. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kex061.020

- 17Egerton T, Diamond LE, Buchbinder R, et al. A systematic review and evidence synthesis of qualitative studies to identify primary care clinicians’ barriers and enablers to the management of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2017;25:625–38. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2016.12.002

- 18Keele University, Arthritis Research UK & National Institute for Health Research. A guide for people who have osteoarthritis. Keele University . 2014.http://www.keele.ac.uk/media/keeleuniversity/ri/primarycare/pdfs/OA_Guidebook.pdf (accessed Feb 2019).

- 19Health and wellbeing boards directory. The Kings Fund. 2018.https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/health-wellbeing-boards-directory-map (accessed Feb 2019).

- 20Health and wellbeing in Shropshire. Shropshire Together. 2018.http://www.shropshiretogether.org.uk/our-priorities/ (accessed Feb 2019).

- 21Arthritis Research UK. Keep moving. Versus arthritis. 2014.https://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/shop/products/publications/patient-information/living-with-arthritis/keep-moving.aspx (accessed Feb 2019).

- 22Arthritis Research UK. Protecting your joints. Versus arthritis. 2013.https://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/arthritis-information/daily-life/looking-after-your-joints/protecting-your-joints.aspx (accessed Feb 2019).

- 23Arthritis Research UK. Osteoarthritis. Versus arthritis. 2018.https://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/shop/products/publications/patient-information/conditions/osteoarthritis.aspx (accessed Feb 2019).

- 24Healthy weight. NHS. 2015.https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/healthy-weight/ (accessed Feb 2019).

- 25Hay EM, Foster NE, Thomas E, et al. Effectiveness of community physiotherapy and enhanced pharmacy review for knee pain in people aged over 55 presenting to primary care: pragmatic randomised trial. BMJ 2006;333:995. doi:10.1136/bmj.38977.590752.0b

- 26Phelan M, Foster NE, Thomas E, et al. Pharmacist-led medication review for knee pain in older adults: content, process and outcomes. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2008;16:347–55. doi:10.1211/ijpp.16.6.0003

- 27JIGSAW-E (Europe). Keele University . 2018.https://www.keele.ac.uk/pchs/implementingourresearch/makinganimpact/osteoarthritisandosteoporosis/jigsaw-e (accessed Feb 2019).

- 28Dziedzic KS, Healey EL, Porcheret M, et al. Implementing the NICE osteoarthritis guidelines: a mixed methods study and cluster randomised trial of a model osteoarthritis consultation in primary care – the Management of OsteoArthritis In Consultations (MOSAICS) study protocol. Implementation Sci 2014;9. doi:10.1186/s13012-014-0095-y

- 29Porcheret M, Main C, Croft P, et al. Enhancing delivery of osteoarthritis care in the general practice consultation: evaluation of a behaviour change intervention. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19. doi:10.1186/s12875-018-0715-8

- 30Porcheret M, Grime J, Main C, et al. Developing a model osteoarthritis consultation: a Delphi consensus exercise. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-14-25

- 31Dziedzic KS, Healey EL, Porcheret M, et al. Implementing core NICE guidelines for osteoarthritis in primary care with a model consultation (MOSAICS): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2018;26:43–53. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2017.09.010