Shutterstock.com

Constipation is one of the most common gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms patients may experience[1],[2]

. As a symptom-based disorder that has no single definition, patients will often have their own opinion of what constipation means to them[3]

. It is therefore necessary to ascertain what a ‘normal’ frequency of defecation is for each patient, as frequency can vary between three times per day to once every three days[2],[3]

.

Constipation affects 1 in 7 adults and 1 in 3 children at any given time; with this symptom being so common, it is not surprising that 66,287 patients in the UK were admitted to hospital with constipation as the main condition (equivalent to 182 people per day) in 2014–2015[4]

.

The incidence of constipation is two to three times higher in women than in men, and is more common with increasing age[5],[6]

. It affects 40% of women during pregnancy; however, this may be owing to the physiological, biochemical and dietary changes that occur during pregnancy[5],[6]

.

This article outlines the symptoms, diagnosis and management options for short-term, occasional constipation (< 5 days), including the appropriate use of stimulant laxatives in line with new safety measures announced by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in August 2020[7]

.

Symptoms

During constipation, the lower GI tract becomes dysfunctional, giving rise to symptoms including:

- Fewer bowel movements than normal;

- Abdominal pain;

- Cramping;

- Nausea;

- Straining during bowel movements[8],[9]

.

Some patients may report a sense of incomplete bowel evacuation, or excessive time spent on the toilet owing to unsuccessful defecation[3]

. Patients experiencing any red flag symptoms (including rectal bleeding, mucus in stools, unexplained weight loss, sudden and severe abdominal pain, abdominal or rectal mass, fever or a persistent change in bowel habit for more than four weeks), as well as those who have a family history of colon cancer, ovarian cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, or who are taking clozapine, should be referred to urgent care immediately[10],[11]

.

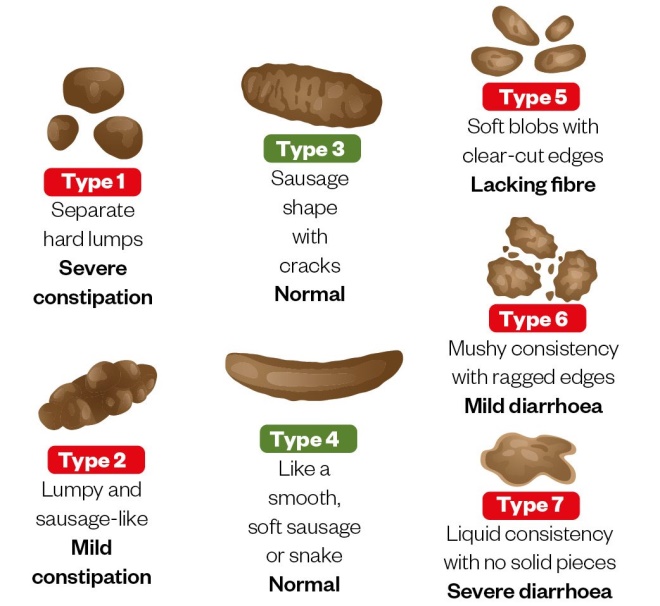

Establishing the nature and texture of the stool, with reference to the Bristol stool chart (also known as the Meyers scale, see Figure), will help determine how constipated the patient may be[12],[13]

. Pain and discomfort from chronic constipation (i.e. having symptoms for more than 12 weeks in the past 6 months) may have an impact on the patient’s quality of life, particularly in older people[10]

. Guidance from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society outlines how pharmacy can support these patients; however, the management of chronic constipation is outside the scope of this article[14]

.

Figure: Bristol stool chart

Source: Shutterstock.com

Causes

Constipation is often multifactorial in adults and can result from systemic or neurological disorders, medications or other organic causes (see Table 1)[10]

. Other contributory factors may include pain, fever, dehydration, lack of dietary fibre and fluid intake, little or no physical activity, psychological issues, toilet training in children and familial history of constipation[10]

.

| Medicines | Organic causes |

|---|---|

| Aluminium containing antacids | Endocrine and metabolic disorders (e.g. diabetes, hypercalcaemia, hypermagnesaemia, hypothyroidism and hyperparathyroidism) |

| Iron or calcium supplements | Myopathic conditions (e.g. amyloidosis) |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. ibuprofen and naproxen) | Neurological conditions (e.g. autonomic neuropathy, multiple sclerosis) |

| Antimuscarinics (e.g. oxybutinin) | Structural abnormalities (e.g. colonic strictures, irritable bowel syndrome, obstructive mass) |

| Antidepressants (e.g. tricyclic antidepressants) | |

| Antipsychotics (e.g. clozapine) | |

| Antihistamine (e.g. loratadine, cetirizine) | |

| Antiepileptics (e.g. carbamazepine) | |

| Antispasmodics (e.g. hyoscine) | |

| Diuretics (e.g. furosemide) | |

| Calcium channel blockers (e.g. verapamil) | |

| Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[10] | |

There are a range of risk factors for constipation, including:

- Behavioural factors

- Low fibre diet or low-calorie intake;

- Difficulty in accessing the toilet, or changes in normal routine or lifestyle;

- Lack of exercise or reduced mobility;

- Limited privacy when using the toilet[10]

.

- Psychological factors

- Anxiety and/or depression;

- Somatization disorders;

- Eating disorders;

- History of sexual abuse[10]

.

- Physical factors

- Female sex;

- Older people;

- Pyrexia, dehydration, immobility;

- Sitting position on a toilet compared with the squatting position for defecation[10]

.

Diagnosis

Taking a thorough history from the patient can rule out many secondary causes of constipation[15]

. An assessment of stool form (see Figure) can be used to estimate the extremes of colonic transit time, since very hard stools or loose stools correlate with slow or rapid colonic transit, respectively[16]

.

Most patients will describe constipation with one or more symptoms. Symptoms commonly include hard stools, infrequent stools (typically fewer than three times per week), a sense of an incomplete bowel evacuation, the need for excessive straining or an excessive time spent on the toilet[17]

. It is important to understand the patient’s perspective and how they feel about their symptoms when considering management.

Differential diagnosis

It is crucial that an assessment rules out other conditions that may warrant further investigation. For example, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) should be excluded. IBS is usually associated with pain during defecation, change in stool frequency and/or change in stool form[9]

.

In general practice, a physical abdominal or internal rectal examination may also be performed, which is often the most revealing part of the clinical evaluation[10],[16]

. When a clinician performs an abdominal or internal rectal examination, they are trying to determine if other issues (e.g. lesions, masses, excoriation, fissures or haemorrhoids) may be causing symptoms[3]

.

Management

The aim of management is to resolve symptoms and help prevent future occurrence of constipation. This can typically be achieved by non-pharmacological measures, but treatment can be recommended if these are ineffective. A recent MHRA update has outlined precautions that need to be taken when advising patients about over-the-counter measures for managing constipation (see Box)[7],[14],[18],[19]

.

Box: Changes to practice as a result of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency safety update

Stimulant laxatives have an acceptable safety profile, have been widely used for many years and are generally used responsibly. However, concerns have been raised regarding the abuse, overuse and misuse of over-the-counter (OTC) stimulant laxatives (e.g. in people with eating disorders, owing to the misconception that they can help them lose weight, and long-term use in older people)[7],[19]

. Following advice from the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM), the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) introduced a package of risk minimisation measures for OTC stimulant laxatives in August 2020 to support correct use and minimise risk of misuse[7]

.

The following summarises the risk minimisation measures relating to stimulant laxatives introduced by the MHRA.

General sales list stimulant laxatives

- New posology: licensed only for people aged 18 years and over;

- Revised indication: for the short-term relief of occasional constipation;

- Reduced pack sizes: standard strength tablets in a pack size of 20, maximum strength tablets in a pack size of 10 and syrups in a pack size of 100ml;

- More prominent warnings included, which state that stimulant laxatives do not aid weight loss[14]

.

P stimulant laxatives

- New posology: licensed only for people aged 12 years and over;

- Revised indication: removal of indications not appropriate for self-care;

- More prominent warnings included, which state that stimulant laxatives do not aid weight loss[14]

.

Updated stimulant laxative products are already available, while existing packs may continue to be available for sale until early autumn 2020. The individual summary of product characteristics should be consulted for more information[7]

.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has produced detailed guidance for pharmacists and pharmacy teams to support the correct use of OTC stimulant laxatives, to prevent misuse in light of these changes and to assist in how to advise at-risk groups (e.g. people with a potential eating disorder, older people and children)[14]

.

First-line management: non-pharmacological

In many cases, occasional constipation is a result of poor diet and lack of exercise. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends first line that underlying causes should be managed and adult patients should be given advice on appropriate dietary and lifestyle measures (see Case study 1)[10]

.

A diet that is high in fibre helps normalise bowel movements by increasing the weight and size of the stool, softening it and helping it to ‘bulk up’, making it easier to pass through the colon[20]

. Fibre also contributes to the maintenance of a healthy gut microbiota[21]

.

Second-line management: pharmacological

If non-pharmacological intervention for the treatment of short-term constipation in adult patients is ineffective, or patients do not experience the desired response, NICE recommends that oral laxatives can be offered using a stepwise approach:

1. Offer a bulk-forming laxative if the patient can drink adequate fluids;

2. If the patient cannot drink adequate fluids and/or if stools remain hard or are difficult to pass, consider adding or switching to an osmotic laxative;

3. If stools are soft but remain difficult to pass, then consider adding a stimulant laxative (see Box 1 and Table 2).

Alternatively, pharmacological management can be used based on symptoms and combination therapies considered as appropriate (see Table 2)[10],[22],[23]

.

| Symptom, drug class and method of action | Medicine | Onset of action | Contraindications and additional information |

|---|---|---|---|

| *Bulk-forming laxatives should be avoided in opioid-induced constipation, as it increases stool bulk, can distend the colon and stimulate perstalsis. Opioids prevent peristalsis of the fibe-increased bulk, which exacerbates abdominal pain and, in some cases, contributes to bowel obstruction[23] . An osmotic laxative and stimulant laxative should therefore be considered. **For short-term, when required basis only. Sources: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[10] , Electronic medicines compendium[22] , Gastroenterology Res Pract [23] | |||

| Low faecal mass; bulk forming laxatives (increases faecal mass, stimulating peristalsis) | Ispaghula husk (3.5g/sachet) | 2–3 days | Colonic atony, faecal impaction, intestinal obstruction, opioid-induced constipation*, palliative patients (owing to long onset of action) and swallowing difficulties. Not to be taken immediately before bed. |

| Sterculia | 2–3 days | ||

| Methylcellulose (500mg tablets) | 2–3 days | ||

| Slow transit; stimulant laxatives (increases intestinal motility**) | Bisacodyl (oral) | 6—2 hours | Acute inflammatory bowel disease, intestinal obstruction and recent abdominal surgery. |

| Bisacodyl (suppository) | 15 minutes to 3 hours | ||

| Senna | 8–12 hours | ||

| Sodium | 6–12 hours | ||

| Glycerol suppository | 15–30 minutes | ||

| Pellet stool; faecal softeners (‘wetting’ lubricants that allow water to penetrate hard faeces) | Docusate sodium (oral) | 12–72 hours | Has both stimulant and softening actions. Peanut allergy for arachis oil. |

| Docusate sodium (enema) | 5–20 minutes | ||

| Arachis oil | 30 minutes | ||

| Hard stool; osmotic laxatives (increases the amount of water in the large bowel) | Lactulose | 2–3 days | Intestinal obstruction, perforation or inflammation. |

| Macrogol | 2–3 days | ||

| Magnesium hydroxide | 3–6 hours | Commonly abused but satisfactory for occasional use; adequate fluid intake has to be maintained. | |

| Magnesium sulphate (Epsom salt) | 2–4 hours | Where rapid bowel excavation is required. | |

| Phosphate enema | 2–5 minutes | Used with caution in renal and cardiac failure. | |

Children

Children aged over 12 years who experience occasional constipation should be advised on maintaining a balanced diet, with enough fluids and behavioural interventions, in combination with macrogol as first-line treatment and stimulant laxatives as second line. Children aged under 12 years with constipation should be referred to a prescriber[14]

.

When to stop treatment

Patients should be advised to gradually reduce and stop the use of laxatives once soft, formed stools are produced without straining at least three times per week. Pharmacists may want to arrange to review the patient regularly and should use clinical judgement to determine whether the condition is resolved or whether further treatment or referral is necessary. The importance of adhering to dietary and lifestyle recommendations should be reinforced to prevent reoccurrence.

Case study 1: an older patient presents with recurrent constipation

A man aged 74 years* presents to the pharmacy asking for something to help him manage his constipation. He explains that it “comes and goes” but he was hoping to “speed it along this time”.

Assessment

It is important to discuss the following with the patient:

- What are the symptoms?

- When did the symptoms start?

- How often has this occurred in the past?

- Has he had a change of diet, routine/lifestyle or medicine?

- Is there any pain when he uses the toilet?

- Does he ever have frequent bowel movements or diarrhoea?

- Is there any blood or mucus when he does defecate?

- Has he tried anything before to manage his symptoms?

After the discussion, it is clear that the patient experiences these symptoms a couple of times per year — usually during the summer months when it is hotter — but other than that, he is “fairly regular”. He indicates that his diet and lifestyle are consistent and that other than some stomach pain and “struggling to go”, he has no other symptoms. The constipation started five days ago but as it usually resolves itself, he says he did not want to “bother the pharmacist” for the first few days. However, owing to the pain he has been experiencing, he decided it was best to come to the pharmacy for treatment.

The patient explains that he spends a lot of time in his garden, goes for regular long walks with his wife and rarely drinks, except for a pint of beer on a Sunday afternoon.

The patient’s medication record reveals that he uses an inhaler (ipratropium) to manage his COPD and takes 100mg sertraline daily. Both have been prescribed for the past year and he takes them as prescribed.

Diagnosis

Since the patient has no change in lifestyle or new medication, it is likely that their advanced age, combined with dehydration caused by the summer heat, has contributed to the patient becoming constipated[10]

.

Advice and recommendations

In this case it is important to explain that the symptoms are potentially a result of dehydration because of warmer weather. The pharmacist should explain that, owing to his age, he is more likely to suffer from constipation but he can help prevent and treat his current symptoms by drinking plenty of water and following the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance on appropriate dietary and lifestyle measures. These include:

- Eat plenty of high-fibre foods (30g per day; e.g. beans, vegetables, fruits, whole grain cereals and bran);

- Eat fewer foods with low amounts of fibre (e.g. processed foods, dairy and meat products);

- Drink plenty of fluids;

- Avoid caffeine;

- Reduce alcohol intake and do not consume more than 14 units per week;

- Stay as active as possible and try to get regular exercise;

- Do pelvic floor exercises (refer to Bladder and bowel community);

- Try to manage stress;

- Do not ignore the urge to pass a stool;

- Try to create a regular schedule for bowel movements, especially after a meal[24]

.

If these measures do not help, advise the patient to return to the pharmacy to discuss other treatment options. However, caveat that if the patient has sudden or severe abdominal pain they should seek urgent care immediately.

Case study 2: a young patient with abdominal pain

A patient aged 16 years* asks to speak to the pharmacist. She would like something to help her go to the toilet as it has been four days and she is experiencing stomach pain.

Assessment

It is important to discuss the following points during the consultation:

- Can she describe the nature of the pain?

- Is it the first time she has had constipation?

- How does this vary from her ‘normal’?

- What is her diet like and what are her activity levels?

- Is she experiencing any stress?

- Does she have any conditions or take any medicines or supplements (prescribed or bought over-the-counter)?

- Has she tried anything to treat it?

- Does she have any medicines in mind?

Some people, in particular young women, may intend to use laxatives to help them lose weight[7],[19]

. Owing to the potential for misuse, abuse and overuse, it is necessary to ensure that appropriate questions are asked to rule this out — for example, “Have you used this medicine before?” or “Are you experiencing other symptoms (e.g. vomiting)?”. It is important to offer opportunities for them to discuss any issues with you — for example, by asking “What other issues would you like to discuss today?”.

The patient describes the pain as cramping but explains that she does not think it is from menstruation as her period was more than a week ago. She cannot remember having constipation before and usually goes to the toilet once per day. She is not currently on any prescribed or over-the-counter medication, except moisturiser for her eczema. The patient regularly runs and has a good diet (i.e. plenty of fibre and fluids). She does not drink alcohol and only has a cup of tea in the morning. The patient explains that she is not stressed and that her routine is “the same as always”. She has not tried anything yet but says that her dad recommended senna as he had used it in the past; however, she does not have a preference.

Diagnosis

Based on the conversation with the patient, it appears that she has uncomplicated constipation. Owing to her age and the mention of senna, it is appropriate to consider abuse; however, the description of symptoms and the lack of product preference indicates that the patient does not intend to abuse laxatives.

Recommendations

As the patient has an active lifestyle and suitable diet, it would be advisable to reinforce these practices, but also suggest that she could take a bulk-forming laxative (e.g. ispaghula husk). As the patient previously mentioned senna, explain to her that this is a stimulant laxative and that, although it can be beneficial to some patients, it is not recommended as the initial treatment for constipation.

Advise the patient that it could take up to three days for the bulk-forming laxative to have an effect. If the bulk-forming laxative fails, advise the patient that they could then try an osmotic laxative, such as macrogol and electrolytes (e.g. Movicol; Norgine Limited). Clarify the directions for use (e.g. reconstitution process) and explain that she should not take it immediately before bed and that she should avoid drinking tea and other diuretics while the symptoms are present as it may worsen them.

If the osmotic laxative fails, the patient may need to trial a stimulant laxative; however, if this is also ineffective after five days, then referral to her GP is recommended.

Case study 3: symptomatic during pregnancy

A pregnant woman aged 32 years* presents to the pharmacy explaining that she has had problems “going to the toilet” and was hoping she could purchase something that would help.

Assessment

During the consultation it is important to ask the following questions:

- How long has she had the symptoms?

- What is regular for her?

- What other symptoms does she have?

- Is this the first time during her pregnancy that she has been constipated?

- Does she take any other medicines (prescribed or over-the-counter) or have any other medical conditions?

- Have there been any recent lifestyle changes?

The patient explains that she is usually regular but has been struggling to go, is passing fewer stools and experiencing irregular bowel movements. She explains her frustration as she has recently got over some reflux. Further questioning on her reflux reveals that she is currently using an aluminium-containing antacid to help relieve her symptoms. She explains that it is a bit painful but more frustrating. The patient adds that her diet is good, but she sometimes has cravings that result in her eating more dairy products. Owing to her pregnancy, she is avoiding coffee and alcohol, but explains she didn’t drink much of either prior to becoming pregnant. The patient is not on any prescribed medicine and, other than the antacid she is currently using, is only taking one other over-the-counter medicine: paracetamol (for back pain that has resulted from her pregnancy).

Diagnosis

Although constipation is common during pregnancy, this tends to be related to difficulty in passing stools. However, this patient appears to be having difficulties passing stools and bowel movements appear to be less frequent than normal. The patient appears to have medicine-induced constipation; while the aluminium containing antacid may be effective at managing her reflux, it may be contributing to her constipation[10]

.

Recommendations

Advise the patient to stop using the aluminium-based antacid and to try an alternative (e.g. a product containing a combination of calcium carbonate/sodium alginate/sodium bicarbonate). Owing to the discomfort caused and the patient’s existing, suitable diet, it would be appropriate to recommend a bulk-forming laxative (e.g. ispaghula husk). This is safe for use in pregnant and breastfeeding patients. Explain that this product can take two to three days to work and that she needs to make up the solution using sachets. Importantly, the patient needs to understand that once the sachet is made up in water, she must drink it as soon as possible as the drink can become ‘set’ and undrinkable as a result. The patient should be encouraged to also increase her fluid intake while taking the bulk-forming medicine. Explain to the patient that a common side effect is flatulence and abdominal bloating; however, with cessation of treatment upon resolution of constipation, this will dissipate.

If the patient continues to struggle with reflux and constipation, she should speak to her GP.

*All cases are fictional.

Mikin Patel is lead pharmacist, gastroenterology at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

References

[1] Keshav S & Bailey A. The Gastrointestinal system at a Glance. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley–Blackwell; 2012.

[2] Rutter P. Constipation and diarrhoea. In: Walker R & Whittlesea C (eds.) Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 5th ed. London: Elsevier; 2012. p. 209–221.

[3] Lembo A & Camilleri M. Chronic Constipation. N Eng J Med 2003;349(14):1360–1368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020995

[4] Coloplast. The cost of constipation report. Available at: https://www.coloplast.co.uk/Global/UK/Continence/Cost_of_Constipation_Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed September 2020)

[5] Suares NC & Ford AC. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106(9):1582–1591. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.164

[6] Shafe AC, Lee S, Dalrymple DS & Whorwell PJ. The LUCK study: laxative usage in patients with GP-diagnosed constipation in the UK, within the general population and in pregnancy. An epidemiological study using the General Practice Research Database (GPRD). Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2011;4(6):343–363. doi: 10.1177/1756283X11417483

[7] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Stimulant laxatives (bisacodyl, senna and sennosides, sodium picosulfate) available over-the-counter: new measures to support safe use. 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/stimulant-laxatives-bisacodyl-senna-and-sennosides-sodium-picosulfate-available-over-the-counter-new-measures-to-support-safe-use (accessed September 2020)

[8] Cleveland Clinic. Gastrointestinal disorders. 2016. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/7040-gastrointestinal-disorders (accessed September 2020)

[9] MD Calc. Rome IV Criteria – Constipation. 2020. Available at: https://www.mdcalc.com/rome-iv-diagnostic-criteria-constipation (accessed September 2020)

[10] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. Constipation. 2019. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/constipation#!prescribingInfoSub:2 (accessed September 2020)

[11] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary. Colorectal Cancer. 2017. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/gastrointestinal-tract-lower-cancers-recognition-and-referral (accessed September 2020)

[12] Lewis SJ & Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32(9):920–924. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Constipation in children and young people: diagnosis and management. NICE [CG99]. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg99/resources/cg99-constipation-in-children-and-young-people-bristol-stool-chart-2 (accessed September 2020)

[14] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Dealing with over-the-counter stimulant laxatives in community pharmacy. 2020. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/pharmacy-guides/dealing-with-over-the-counter-stimulant-laxatives-in-community-pharmacy#Long%20term (accessed September 2020)

[15] Tack J, Müller-Lissner S, Stanghellini V et al. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic constipation–a European perspective. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;23(8):697–710. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01709.x

[16] Jamshed N, Lee Z-E & Olden KW. Diagnostic Approach to Chronic Constipation in Adults. Am Fam Physician 2011;84(3):299–306. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/0801/p299.html (accessed September 2020)

[17] Andrews CN & Storr M. The pathophysiology of chronic constipation. Can J Gastroenterol 2011;25 Suppl B(Suppl B):16B–21B. PMID: 22114753

[18] Robinson J. Medicines regulator to publish review into safety of OTC laxatives. Pharm J online. 2020. Available at: https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/news-and-analysis/news/medicines-regulator-to-publish-review-into-safety-of-otc-laxatives/20207696.article?firstPass=false (accessed September 2020)

[19] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Public Assessment Report of over-the-counter stimulant laxatives: benefit-risk review. 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/public-assessment-report-of-over-the-counter-stimulant-laxatives-benefit-risk-review (accessed September 2020)

[20] Forootan M, Bagheri N & Darvishi M. Chronic Constipation: a literature review. Medicine 2018;97(20):1–9. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010631

[21] Shah A, Morisson M & Holtmann G. A novel treatment for patients with constipation: Dawn of a new age for translational microbiome research? Indian J Gastroenterol 2018;37(5):388–391. doi: 10.1007/s12664-018-0912-3

[22] Electronic medicines compendium. Resolor 1mg film-coated tablets. 2019. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/584/smpc (accessed September 2020)

[23] Kumar L, Barker C & Emmanuel A. Opioid-induced constipation: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and management. Gastroenterology Res Pract 2014;2014:141737. doi: 10.1155/2014/141737

[24] NHS Eat well. How to get more fibre into your diet. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/how-to-get-more-fibre-into-your-diet/ (accessed September 2020)