JL / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Acute cough, one of the most common presentations in primary care, is often associated with viral upper respiratory tract infections, such as cold or flu[1]

, and can be a presenting symptom of more than 100 clinical conditions of the respiratory system[2]

. Acute cough is estimated to cost the UK economy around £979m per year, taking into account factors such as absenteeism from work and associated healthcare costs[1]

.

Initiated both reflexively and voluntarily, cough is a necessary reflex and helps to remove fluid and mucus from the airways. There is no ‘normal’ pattern of coughing, nor any data on how often a healthy person should cough; therefore, it is important to understand when a cough becomes clinically significant.

Pharmacists and healthcare professionals should also be able to promote antimicrobial stewardship through promoting self-care and infection prevention for cough, with use of antibiotics where appropriate.

Pathophysiology

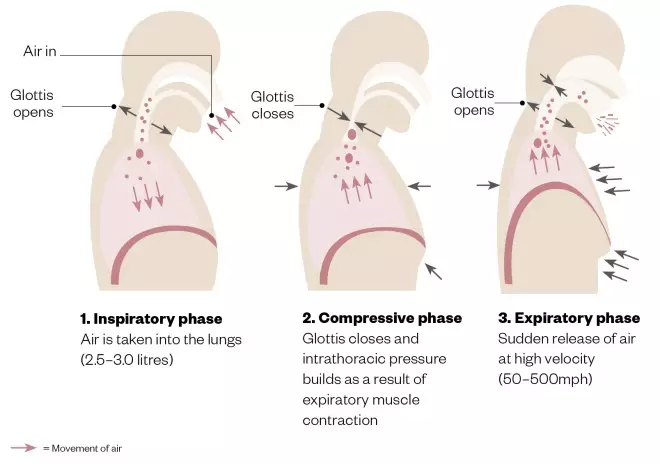

There are three defining features of the mechanism of a cough (see Figure)[2]

:

- There is an initial deep breath (inspiratory mechanism);

- The closing of the epiglottis to entrap the air within the lungs (compressive mechanism);

- The opening of the glottis, closure of the nasopharynx and expiration through the mouth with noise (expulsive mechanism).

Figure: The three phases of cough

All three phases must function adequately for cough to be effective.

Diagnosis

When diagnosing a cough, it is important to gain information on the patient’s cough characteristics (see Box), smoking history, occupational history and medication history. An online computerised clinical smoking load/pack years calculator can help to find out more about the patient’s lifetime smoking exposure (see ‘Useful resources’).

Box: Types of cough and their associated signs and symptoms

The two most common types of cough are a dry cough and a chesty/productive cough:

Dry cough

A non-productive cough can be caused by the following:

- Asthma;

- Environmental irritants or medicines such as angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

Common signs include lack of phlegm (mucus) and the patient may describe it as “tickly”.

Chesty/productive cough

Characterised by greater than 30mL of sputum produced in 24 hours. Common causes include:

- Upper airway cough syndrome (previously referred to as post-nasal drip syndrome);

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease;

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

; - Infection caused by a bacteria or virus.

Common symptoms of an infectious cough include a fever, runny nose and malaise.

Source: Chung KF & Widdicombe JG. Cough: causes, mechanisms and therapy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2003

Acute cough

Defined as a cough persisting for less than three weeks[3]

, acute cough is usually self-limiting and can be caused by viral infections, bacterial infections or inhalation of a foreign irritant.

The choice of diagnostic test depends on the origin of the cough, allergy testing, throat swabs and examination of the throat.

If the patient also presents with a sore throat, online tools such as FeverPAIN[4]

or the Centor criteria[5]

can be used to determine the likelihood of them having a streptococcal infection that may require antibiotics[6]

.

Subacute cough

Defined as a cough lasting for between three and eight weeks[3]

, subacute cough is most commonly caused by airway hyper-responsiveness following specific infections such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae

[4]

. Alternatively, it may be following resolution of

Bordetella pertussis

infection, where a post-infectious cough persists[3]

).

Subacute cough is also often self-limiting, however, during this time it is important to monitor the improvement of the cough and identify red flags (see below)[1]

.

Chronic cough

A cough lasting for more than eight weeks is defined as chronic[3]

. It is most commonly caused by smoking, asthma, upper airway cough syndrome (previously referred to as post-nasal drip syndrome), upper respiratory tract infection or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD). The clinical assessment of a chronic cough includes[2]

:

- Cough severity (e.g. is there sputum or blood associated with the cough?);

- Frequency (e.g. is the cough occurring throughout the day or is it worse in the morning or at night?);

- Impact on the patient’s well being (e.g. are they not able to do things they previously could?).

A chest X-ray can be used to determine if the patient’s chronic cough is a symptom of a more serious condition, such as pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary neoplasm or pneumonia.

Identifying red flags

High-risk patients should be promptly identified, for example, those with a weakened immune system as a result of chemotherapy or diabetes, and older patients.

Other red flags, in both smokers and non-smokers, include[7],[8]

:

- Abundant production of sputum;

- Fever and sweats;

- Considerable breathlessness;

- Unexplained weight loss;

- Coughing up blood or red phlegm;

- Heartburn;

- Localised chest pain;

- Swollen glands;

- If the cough quickly gets worse or the patient cannot stop coughing;

- If the cough is persistent (e.g. it lasts for more than three weeks).

When diagnosing chronic cough, it can be difficult to differentiate the common causes, while ensuring that rare but serious causes are not missed. For instance, asthma is a common cause of chronic cough in primary care, as well as upper airway cough syndrome and GORD — known as the pathogenic triad[8]

. In a study by Palombini et al. of 78 adult non-smokers, 94% were indicated with one or a combination of the pathogenic triad as the cause[9]

.

Other signs of serious illness in acute, subacute and chronic cough include[10]

:

- Respiratory rate of more than 30 breaths per minute;

- Tachycardia greater than 130 beats per minute;

- Systolic blood pressure less than 90mmHg or diastolic blood pressure less than 60mmHg (unless this is normal for them);

- Oxygen saturation less than 92%.

Emergency admission should be arranged if any of these red flags are identified. In acute cough, additional red flags include clinical features of suspected pulmonary embolism (e.g. pleuritic chest pain, tachypnoea and/or features of deep vein thrombosis[11]

) and unexplained shortness of breath[10]

.

Case studies

Case study 1: a patient with an acute cough that has lasted for less than three weeks

A 21-year-old man* presents to his local pharmacy with a cough that has been bothering him and asks to speak to the pharmacist.

Assessment

The following areas are discussed with the patient:

Cough characteristics

- When did the cough start?

- Is the cough dry or productive (i.e. producing phlegm)?

- If the cough is productive, what colour is the phlegm?

- Is there a pattern to the cough or does it have any triggers?

Patient medical history

- How are you feeling (e.g. are you experiencing a fever, a runny nose or malaise)?

- Do you have any relevant medical conditions?

- Are you taking any medicines?

- Have you tried any over-the-counter (OTC) treatments?

- What do you do for a living?

- Do you have any pets?

- Have there been any changes to your lifestyle recently?

- Smoking history (including if the patient has given up smoking);

- What type of tobacco do/did you smoke?

- How many do/did you smoke a day?

- How long have you smoked for/did you smoke for?

- Social history — alcohol and recreational drugs;

- How many units of alcohol do you consume during a week?

- Do you smoke or take any recreational drugs?

On answering the questions, the patient explains that he has had a cough for two days and it is dry in nature with no sputum, but he is coughing frequently and it is keeping him up at night with a headache. He is currently a student, a non-smoker and drinks occasionally. He has no relevant medical history and has not taken any medicines or OTC treatments.

Diagnosis

Since the patient has no comorbidities or symptoms to indicate a more serious condition, it is likely that he has an acute viral upper respiratory tract infection (e.g. a cold) that will resolve itself in three to four weeks without antibiotics[12]

.

Advice and recommendations

The patient is advised to take simple analgesia for the headache and pain associated with the cough (1g of paracetamol up to four times per day). The patient is told he should rest, drink plenty of fluids[8]

and avoid exercise while unwell, because this can trigger a cough. Since it is likely a viral infection, the patient should be told that antibiotics are not needed along with an explanation of why.

If the cough has not gone within three weeks or if it changes in nature (e.g. it becomes productive with green or red phlegm), the patient is advised to visit their GP for further investigations. If the patient is concerned in the meantime, they are advised to return to the community pharmacy.

Case study 2: a patient with a chronic cough that has lasted for more than eight weeks

A 42-year-old woman* presents to the pharmacy with an ongoing cough that is causing her problems and would like to buy some cough medicine.

Assessment

The following areas are discussed with the patient:

Cough characteristics

- How long have you been experiencing the cough?

- How did the cough start? Was its onset gradual or sudden?

- Is there pain associated with the cough?

- Is the cough dry or productive (producing phlegm)? (If there is an ongoing dry cough, this would be considered as a red flag);

- If there is phlegm, what colour is it? (If there is haemoptysis [blood present in any phlegm], this would be considered as a red flag);

- Is there variation in the cough (i.e. is it better or worse at night)?

- Is there anything that exacerbates the cough?

Patient medical history

- How are you feeling (e.g. are you experiencing a fever, a runny nose or malaise)?

- Do you have any medical conditions?

- Are you currently taking any medicines?

- Have you tried any over-the-counter (OTC) treatments?

- Have you been treated for a recent infection?

- Have you had the flu jab this year?

- What do you do for a living?

- Do you have any pets?

- Smoking history (including if the patient has given up smoking);

- What type of tobacco do/did you smoke?

- How many do/did you smoke a day?

- How long have you smoked for/did you smoke for?

- Social history — alcohol and recreational drugs;

- How many units of alcohol do you consume during a week?

- Do you smoke or take any illicit substances?

Quality of life

- Does the cough affect your quality of life?

- Are you able to complete tasks (e.g. walking upstairs) as you had done prior to the cough starting?

The patient answers the questions and explains that she is an office worker, has been smoking 20 cigarettes per day since the age of 15 years and has had a cough for the past three months.

She has not wanted to bother her GP as the cough is persistent throughout the whole day and is dry in nature. She has been having pain in her ribs, but she feels this is only owing to her coughing constantly. She has noticed recently that she has been feeling more breathless and is unable to walk up the hill to her house without stopping, like she did previously. She has also noticed that, in the past couple of weeks, there have been red blood spots on her tissue when she coughs.

Diagnosis

The patient has a chronic cough with several red flag symptoms (i.e. haemoptysis, pain and shortness of breath) and should be referred urgently to her GP or a respiratory specialist for further investigation. When questioning a patient who presents with a chronic cough, it is important to determine the presence of any red flag symptoms. Furthermore, it is worth knowing the demographics and epidemiology of a chronic cough to understand where to refer; chronic cough is most prevalent in middle-aged women, especially those who have a significant smoking history as the smoking effects are cumulative[1]

.

Advice and recommendations

The patient is advised to book an urgent appointment with her GP who will likely refer her to a specialist respiratory doctor. The patient should not be sold any cough suppressants.

The presence of several red flag symptoms could indicate underlying conditions such as lung cancer. This, however, cannot be diagnosed without referring to a specialist for physical examination and radiography. It is important not to worry the patient, but to express the urgency of further investigation.

Signposting the patient to smoking cessation services would also be beneficial.

Case study 3: cough in a child

A parent brings her four-year-old son* in to the pharmacy and asks to speak to the pharmacist because her son has a loud cough and a runny nose.

Assessment

Childhood coughs and respiratory illness should be treated differently to adults as common coughs and colds in adults can be life threatening in children. The prevalence of cough in children is high; therefore, it is important to have a clear history on the child’s cough to determine if it is abnormal.

When questioning the parent about the child’s cough, it is important to determine the nature of the cough and the impact it is having. The following areas are discussed:

Cough characteristics

- When did the cough start?

- Is the cough dry or productive?

- Has the child been feeling unwell recently (e.g. experiencing fever, runny nose, aches, pains and sore throat)?

- Is there wheeze associated with the cough?

- Is the child experiencing any stridor, tachypnoea or swallowing difficulties?

- Could this cough be aspiration of a foreign object?

Patient medical history

- Does the child have any medical issues?

- Are they currently taking any medicines?

- Is this the first presentation of cough?

- How old is the child and are they up to date with their childhood vaccination schedule?

- Has the cough had an impact on the child’s wellbeing (e.g. poor growth, finger clubbing, haemoptysis or shortness of breath)? (Any of these would be an immediate red flag referral to their GP).

The parent explains that her son has been coughing for the past three days, mostly at night. It is a dry cough that sounds like a barking noise and his voice is a bit hoarse. The child has no previous respiratory symptoms nor has been hospitalised for any infections. He is up to date with his vaccination schedule.

On examination, the child looks well apart from a runny nose and he does not have a temperature or shortness of breath.

Diagnosis

The child most likely has croup. This is a common viral illness in a child, which causes a characteristic ‘barking’ cough. The illness is self-limiting and will not be improved by over-the-counter cough remedies or antibiotics.

Advice and recommendations

It is explained to the parent that the illness is self-limiting, their child’s symptoms should improve within 48 hours and that he should be well in a week. The parent is advised to check on the child regularly, including through the night[13]

. It is recommended to give the child plenty of fluids, but that the illness will not be improved by over-the-counter cough remedies or antibiotics[14]

.

It is unusual for the symptoms to last longer than a few days. However, if the symptoms do not improve, the child needs to be referred to their GP. If the child is struggling to breathe, their skin or lips look blue/grey, or they are unusually quiet or still, call 999[13]

.

*All cases are fictional.

Useful additional resources

- Smoking Pack Years. 2007. Available at: https://www.smokingpackyears.com/instructions

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS). Cough. 2015. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/cough

- NHS Choices. Cough. 2017. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cough

References

[1] Morice AH, McGarvey L & Pavord I. Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax 2006;61(Suppl 1):i1–i24. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.065144

[2] Chung KF & Widdicombe JG. Cough: causes, mechanisms and therapy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2003

[3] De Blasio F, Virchow JC, Polverino M et al. Cough management: a practical approach. Cough 2011;7(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-7-7

[4] University of Oxford. FeverPAIN Clinical Score. 2013. Available at: https://ctu1.phc.ox.ac.uk/feverpain/index.php (accessed August 2019)

[5] MDCalc. Centor Score. 2018. Available at: https://www.mdcalc.com/centor-score-modified-mcisaac-strep-pharyngitis (accessed August 2019)

[6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sore throat (acute): antimicrobial prescribing. NICE guideline [NG84]. 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84 (accessed August 2019)

[7] NHS Choices. Cough. 2017. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cough (accessed August 2019)

[8] Barraclough K. Chronic cough in adults. BMJ 2009;338:b1218. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1218

[9] Palombini BC, Villanova CA, Araújo E et al. A pathogenic triad in chronic cough: asthma, postnasal drip syndrome, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Chest 1999;116(2):279–284. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.2.279

[10] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS). Cough. 2015. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/cough (accessed August 2019)

[11] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS). Pulmonary Embolism. 2019. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/pulmonary-embolism#!diagnosisSub (accessed August 2019)

[12] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cough (acute): antimicrobial prescribing. NICE guideline [NG120]. 2019. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng120 (accessed August 2019)

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS). Croup. 2019. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/croup#!topicSummary (accessed August 2019)

[14] NHS Choices. Croup. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/croup (accessed August 2019)