Shutterstock.com/Mclean

Models of healthcare provision are continuously evolving to ensure service delivery meets the needs of the local population[1]

.

Within secondary care, lead pharmacists are often asked to establish and provide pharmacy services to new wards and departments where they can provide support for more complex patients and conditions. Opportunities are not restricted to the secondary care setting — for example, with an increased number of pharmacists working in GP practices there may be opportunities to take on new clinical roles[2],[3]

.

This article describes the process of setting up a pharmacy service for a new clinical area within Wirral University Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, specifically implementing a pharmacy service in a newly developed midwifery-led unit. This includes important considerations, such as:

- Agreeing the scope of the clinical service;

- Identifying resource requirements (e.g. consumables and staffing);

- Identifying governance requirements;

- Implementing a stakeholder review process;

- Considering logistical factors that may affect service delivery.

This maternity-led unit was located remotely from the main acute trust site and provides an alternative birth environment for low-risk pregnant women, in addition to the facilities available at the acute trust.

Step 1: Identify opportunities

The first step in any such project is identifying whether there are opportunities to contribute to another project’s goals or to improve on existing services (e.g. finding an unmet need in practice or reflecting on the services already available). Pharmacists may determine potential targets for new or expanding services by attending the relevant management meetings in which business development opportunities are discussed. However, depending on the size and scope of the organisation, this may not be possible.

For this example, the opportunity to contribute to the trust’s new midwifery-led service was identified by the lead pharmacist for the Women’s and Children’s Division when the proposed new service was being discussed in the division’s management meeting. The divisional lead pharmacist attended the meeting; however, pharmacists are not always members of the business committees that they provide services to. There is often the need to prove the value of existing services to decision makers, to encourage hospital managers and clinicians to consider pharmacists as core service providers as opposed to support services. If this can be achieved, it is much more likely that pharmacist presence in meetings in which business decisions are made will be requested, ensuring opportunities are not missed.

Step 2: Define goals and roles

Before starting any project, the goal or outcome needs to be clearly defined and agreed with all relevant parties[4],[5]

. In order to meet each objective successfully, it is important to consider the people who will be directly and indirectly affected at each step of the project, including those involved with delivery of the service once the project is completed[4],[5]

.

Success requires all roles to be clearly identified and that the individuals involved share the vision and support the proposal before implementation begins[4],[5]

. Although the strategies used to do this are outside the scope of this article, it is important to tailor communications to the person or role that being liaised with. In this example there was need to communicate:

- The benefits of improving patient experience and safety to the nursing/midwifery staff;

- Finances and throughput to the managers;

- Clinical quality and corporate risk to the medical lead.

In general, the main roles in delivering any project are listed and defined below.

Project sponsor

The sponsor is the individual/s, often a manager or director, with overall accountability for the project[4],[5]

. Their primary concern is making sure the project delivers the agreed business and health benefits[4],[5]

.

The staff members undertaking this role have overall responsibility and authority, and consequently approve all decision making. It is important that they are kept informed and updated with the progress of the project.

In this example, the sponsors were the trust’s director of pharmacy and medicines optimisation, the divisional director of nursing and midwifery and the divisional medical director for women’s and children’s services.

Primary stakeholders

Anyone who stands to be directly affected, either positively or negatively by the outcomes of the project, is considered a primary stakeholder[4],[5]

. For example, when creating the new midwifery-led service, the primary stakeholders were the outpatient matron for maternity services, the team of midwives that would be running the service on a day-to-day basis and the patients who would be using the service.

Secondary stakeholders

People who are indirectly affected by the outcomes of the project are considered secondary stakeholders[4],[5]

. For the midwifery-led service, this included:

- The pharmacy support services operational manager supplying medicines to the unit;

- The estates manager ensuring the medicines storage cupboards were installed in appropriate areas and that the unit was secure;

- The finance manager ensuring that medicines budgets and costs were allocated correctly for the unit.

Project champion

The person implementing the project and taking responsibility for driving the project forward, ensuring tasks are completed in accordance with deadlines, is known as the ‘project champion’[4],[5]

. They ensure stakeholders and sponsors are communicated with and are committed to the aims and objectives of the project. This is necessary as failure to identify or successfully communicate with a sponsor or primary/secondary stakeholder can put a project at risk.

In addition, the champion is responsible for identifying a project’s strategic objectives and making sure these are agreed with the stakeholders and sponsors. Essentially, they are responsible for developing the action plan, and so the ultimate success of any project often hinges on having an effective champion[5]

.

In this example, the project champion was the lead pharmacist for women’s services. They were chosen because they had direct working relationships with the project sponsor, and the primary and secondary stakeholders, which would help maintain effective communication between all groups and, as a result, keep track of individual tasks.

Step 3: Develop the hospital service specification

The service specification details the nature of the proposed service. It should consider:

- What types of patients will be treated;

- What treatments will be offered;

- What tasks will be undertaken;

- Which members of the pharmacy team will be involved with tasks;

- When these tasks will be delivered[6]

.

These specifications should be agreed with relevant people within the organisation, which may include the clinical service lead or department head, and should be signed off by the project sponsor.

Failure to map activity or describe services provided in enough detail may lead to two potential problems:

- The team over-extending themselves owing to scope creep (also known as service creep), as they attempt to meet the expanding demands of a service that was not originally planned for;

- The service not meeting the expectations of the clinical service lead, stakeholders, sponsor or service users[6]

.

Scope creep is defined as continuous or uncontrolled growth in a project, which is considered harmful to the success of the project. This is often mainly due to poorly defined project objectives or poor communication of these objectives[7]

.

Step 4: Determine resource requirements

The following factors should be considered as they affect cost estimates and budgets for both the staffing and medicines (consumables) that are required to deliver the new service.

Who are the patients?

It is important to establish from the outset whether the proposed service users will be new patients or if they are currently being managed in another part of the organisation. If the proposed patient population is completely new to the organisation, considerations regarding funding to generate extra capacity within the existing pharmacy team to deliver this extra activity will be required.

If the patients are treated in the hospital, current staffing and consumable budgets may be less of an issue, but the impact of split-site services on staffing (such as travel and continuity of service in both locations) should be considered.

When creating the midwifery-led service, the service users were patients that would otherwise be using the trust’s existing services and, therefore, did not result in an increase in overall patient numbers. Costs were accounted for by the overall trust budget for midwifery services, so funding was re-allocated proportionately based on patient numbers migrating from the acute trust to the new midwifery-led unit (MLU). The proposed MLU would have relatively few patients of low clinical acuity, requiring low-risk medicines and minimal requirements for off-site visits. As these patients were not new to the organisation, this meant that a clinical pharmacy service could be provided utilising the existing pharmacy staff to backfill for off-site visits to the unit when required.

Medicines-related costs incurred for the patients at the MLU were for procuring, transporting and storing medicines; and staff time to undertake medicines-related audits and any clinical activity required. These costs were paid for by a corresponding decrease in costs to the service to the main hospital (i.e. the location in which these patients would have been treated prior to the MLU being set up).

What medicines will be used?

There is a need to consider how medicines are likely to be used and when in the patient journey they will be required. Understanding what medicine prescribing and administration tasks are likely to occur at each point of the patient journey will help with the development of a pharmacy service specification. Consideration should be given to the patient population, the nature of the conditions being treated and the degree of clinical risk of associated medicines. This should include intravenous fluids, medical gases and dressings.

Who will be supplying these medicines?

Mapping what each healthcare professional is doing at each step of the patient journey is critical for medicines-related processes to be carried out appropriately. A review of the number and type of medical, nursing and other staff members working in the new unit should be undertaken with the multidisciplinary care team to check there is capacity for all potential medicine-related activity that may be required at each stage of the patient journey.

Failure to perform this review can potentially lead to the correct processes not being followed as the correct staff may not be available. This may result in increased clinical risk. Clinical risk is defined as the probability that a hazard will give rise to harm in the healthcare setting[7]

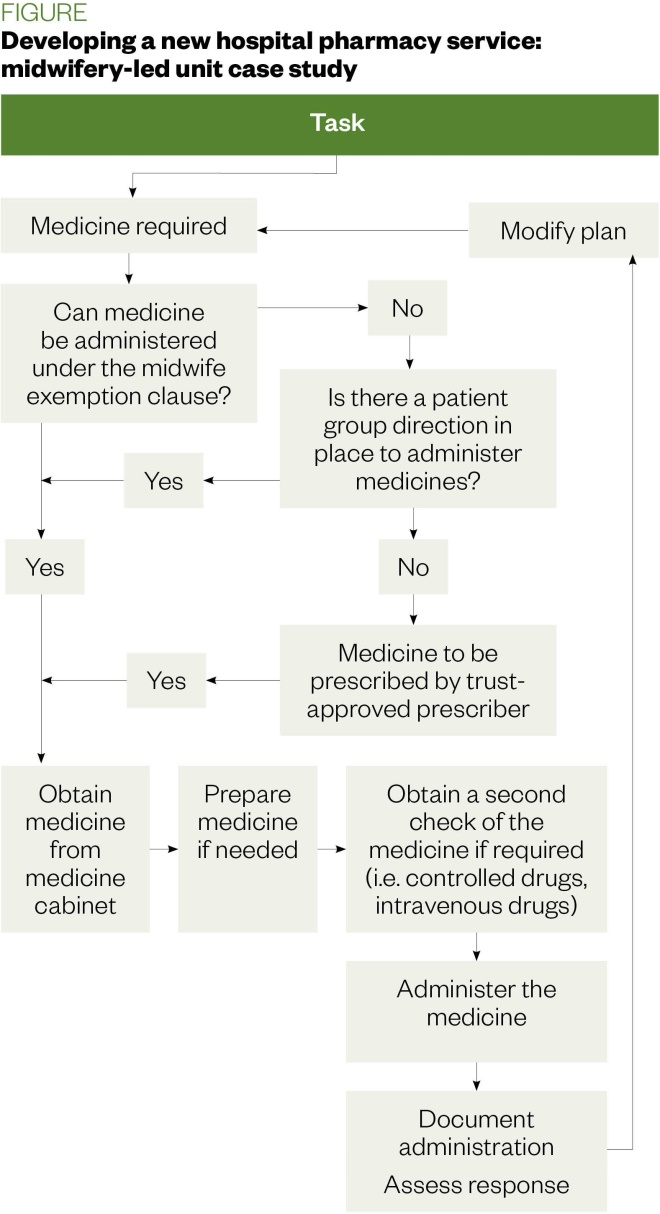

. How this review is completed for the example of creating a new midwifery-led service is described in Figure 1.

Figure: Flow diagram to map medicines processes and identify staffing requirements when developing a new hospital pharmacy service

Any gaps in staffing can be mitigated by introducing changes to the medicines system, or by introducing additional pharmacy staffing to undertake activities, such as prescribing, supplying or medicines administration[8],[9]

.

It is important to note that roles such as non-medical prescribers and assistant practitioners have a limited scope with medicines when compared with medical and nursing staff. For example, most acute trusts require non-medical prescribers to prescribe within the restriction of a personalised medicines formulary, and assistant practitioners (if the role is supported by the organisation) to complete local education and training packages before they administer medicines. It is important to note that patient group directions (PGDs) or midwife exemptions (MEs) may need to be considered if prescribers will not form part of the new team. Paracetamol, diclofenac, cyclizine and morphine are available through ME legislation, while the diptheria, tetanus toxoids and pertussis vaccine is used by midwives under a locally agreed PGD[10]

.

Patients administering their own medicines may be considered if local policy allows, as well as training medicines management technicians (MMTs) to administer specific medicines. Some trusts have developed a structured training programme for MMTs in the administration of medicines, detailing the competencies required and witnessed activities to demonstrate these. For example, this could include putting MMTs through medicines training that the nursing staff are trained on, then adding additional on-the-job aspects to reflect specific elements of the role. Trust policies, procedures and approval processes must describe any activity that is outside what is currently recognised practice to ensure that the staff involved are covered by vicarious liability.

If additional pharmacy staffing resources are required, it may be necessary to prepare a business case to request funding[11]

. When determining staffing requirements, it is important to remember that recruitment may be difficult if the requirement is less than 0.5 whole-time equivalent; therefore, it may be necessary to combine this role with another to increase the number of hours to make the opportunity attractive to potential employees.

For the MLU, the lack of doctors on site meant that patients who required medicines that were not available via PGD or ME could not be treated safely. This resulted in the exclusion of patients who would potentially require medicines that needed prescribing. This resulted in the need to develop strict criteria to transfer patients from the MLU to the acute trust if the patient’s condition changed to require medical attention.

How will medicines activity be recorded?

Systems that already exist within the organisation should be used to document the prescribing and administration of medicines. However, different systems may be required if the organisation prescribes electronically and the new service area does not facilitate this practice. If paper documents (i.e. drug charts) are required, the systems for ordering and delivery needs to be agreed with the new unit manager.

If suitable drug charts are not already in use within the organisation, new charts need to be designed by appropriate clinical staff, approved by the relevant committee and introduced to the organisation. For the MLU, the existing drug charts used in the main hospital were suitable for use in the new unit.

What level of pharmacy service should be offered?

The level of service delivery may range from a medicines supply-only service (with overarching governance arrangements to ensure legislative requirements for medicines management are met), to the introduction of a clinical pharmacy service, which may include clinical pharmacists, pharmacist prescribers, MMTs and support staff.

How medicines will be ordered, delivered, stored, prescribed, administered, governed and disposed of will also require consideration. For example, medicines of relatively low-risk (e.g. topical lidocaine/adrenaline for surface anaesthesia prior to suturing) could be administered by a nurse or midwife under a PGD and would require limited preparation prior to administering. Conversely, a new service providing complex surgery could involve administration of high-risk medicines (e.g. controlled drugs or epidurals) that require prescribing, preparing and administering by an anaesthetist.

If the patient groups are merely being transferred from another area within the same organisation, the trust’s existing clinical guidelines, policies, procedures and formularies can often be adopted. If the patient group is completely new to the organisation, then these governance documents tools may need to be created, which could require a ‘start-up’ resource (see useful resources). For this example, utilising the existing formularies, guidelines and policies saved time and effort as there was no need to create new versions.

The amount of funding required for the service will depend on the type and volume of activity that the service will deliver (see Table).

| Clinical service provision | Range of pharmacy services provided |

|---|---|

| Outpatient clinic (general) |

|

| Outpatient clinic (specialist) |

|

| Hospital ward, low acuity, low turnover |

|

| Hospital ward, low acuity, high turnover |

|

| Hospital ward, high acuity, or moderate acuity with high turnover |

|

| Critical care departments (i.e. intensive care unit, high dependency unit, special care baby unit or coronary care unit) |

|

Step 5: Logistical considerations

Medicines supply

The following factors should be considered and addressed to ensure that stock medicines are available and replaced when used on the new unit:

- Agree a medicines stocklist with the area’s clinical service lead (this will usually be a doctor who is accountable for the clinical activity that will occur in this area);

- Create the stocklist with the department’s electronic medicines ordering system (for support staff to use to replenish stock);

- Agree the frequency of the medicines top-up service with the distribution lead;

- Agree the type of medicines top-up service with the distribution lead (i.e a “put away service” where the pharmacy assesses stock levels, order, pick and put away stock; or a “unit self-top up” where the staff working in the unit perform this function).

There are several factors to be considered when making this decision, including:

- The number of patients using the unit;

- The number of doses required per patient;

- The likely expiry dates of each medicine stocked;

- The physical location of the unit in relation to pharmacy stores;

- The delivery method (e.g. delivery by pharmacy staff, the trust’s porter service or collection from the pharmacy by unit staff);

- Risk assessments and insurance policies that may be required if medicines needs to be transported to an external location;

- Cold chains that may need to be monitored to give assurance regarding appropriate transport;

- Extra funding that may be required to pay for the pharmacy distribution service if an extensive service is requested.

It is important to note that if it is decided that nursing/midwifery staff working in the new area will self-manage stock checks and the ordering of medicines, a stock- and date-checking system and pro forma should be put in place to mitigate the risk of administration of expired medicines. These will need to be locally developed.

For the MLU, there was a need to limit medicines that could not be managed at the unit. For example, methadone as a medicine that requires specialist prescribing would not be stocked; therefore, this means if a patient is opiate-dependent they would be excluded from treatment in the unit as it would not carry this medicine.

Financial considerations

There is a need to speak with the divisional/directorate finance officer/accountant to understand:

- What activity they are expecting to see against this newly created cost code;

- That they have allocated the correct budget to this cost code;

- That they are aware of the start date that they will see activity from.

It should be noted that failure to follow these steps may lead to inaccurate financial reporting.

Medicines storage

Approved medicine cabinets that are compliant with medicines storage legislation will be required[12],[13],[14]

. Fridges, freezers, intravenous fluid racking, gas cylinder racking and controlled drug cabinets all need to be considered depending on the agreed stocklist.

The proposed site should be visited and reviewed, paying particular attention to medicines storage and preparation area requirements. Guidance from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society states that medicines must be stored inside a locked container (i.e. drugs cabinet, fridge) inside a locked room. Access to the room could be via a digital code, key or fob, and access to the medicine’s containers could be via a key or digital code[13]

.

If using keys, a designated registered healthcare professional should hold the keys at all times and there should be a system in place for documenting key reconciliation if transferring from one healthcare professional to another[13]

. This is not required if using codes; however, a process for regularly changing the codes (suggested at least annually) is required. Other medicines storage standards apply, such as recording daily room/fridge temperatures. For more information, individual trust’s medicines management policy should be consulted.

If it is anticipated that medicines will require preparing in the unit, then a clean bench area with access to a clean sink is essential[14]

. The room should not be used for any non-medicines-related functions (e.g. bodily fluid disposal). Computers located in medicines rooms are ideal to enable healthcare professionals to source medicines information if needed.

Step 6: Governance considerations

Governance reporting arrangements should be reviewed at this stage to ensure any location-specific audit data are collected to demonstrate compliance with medicines storage requirements for the new location, such as temperature monitoring and medicines key reconciliation[13]

.

NHS hospitals also collect various data for regular reports and audits, such as:

- Financial data (e.g. drug spend);

- Operational data (e.g. speed of processing discharge prescriptions, medicines reconciliation, controlled drug storage, relevant temperatures and key reconciliation);

- Clinical data (e.g. antimicrobial usage, missed doses and clinical interventions)[15]

.

The people that are involved in collecting and reporting these data must be informed of the new unit to prevent data being missed or being attributed to the incorrect reporting structures.

Step 7: Stakeholder review and sign-off

Once all of these factors have been reviewed and the remit of the planned service and its delivery is established, the proposal should be discussed and agreed with sponsors before being taken through the division’s management meeting (see Step 1) for approval within the organisation, according to the trust’s governance framework. Before the new service is launched, it is important to go through the final checklist to make sure everything is in place (see Box).

Box: Final checklist before launching the new service

- Is the budget in place?

- Have the medicine stock lists been created?

- Have the logistics (how will medicines be ordered, delivered, stored, prescribed, administered and disposed of) been defined and agreed?

- Has the clinical pharmacy service been defined and agreed?

- Is the relevant staffing in place?

- Has training been identified and delivered?

- Are guidelines, policies, procedures, formularies, personal non-medical prescriber formularies and patient group directions in place?

- Has the process for medicine top-ups and deliveries been arranged?

- Have the necessary medicines storage units been ordered and installed?

- Have the governance arrangements been made for controlled drugs, storage audits and clinical audits?

- Is the new area registered as a trust premise with the Care Quality Commission.

- Have all relevant parties confirmed that they are ready for the implantation date?

For the midwife-led example, this checklist was used to identify that all of the important steps in this process have been completed and that relevant stakeholders were ready to implement any changes in their practice in time for the go-live date. The unit has been open since May 2018 and is the first midwifery unit in the UK to be opened in a community setting in an environment away from a busy acute trust, delivering 66 babies in its first 12 months[16]

.

Summary

The specifications for a given trust must be met by any hospital pharmacy team considering a new service. The following points provide a broad overview of some of the issues that may be encountered:

- The level of pharmacy service required (both supply and clinical service to be considered);

- How it will be funded;

- The security and layout of the unit (to ensure appropriate medicines storage is achievable);

- The stock medicines required and their quantities;

- The requirements for medicines administration and documentation;

- The staffing of other healthcare professionals.

Taking on board the examples in this article can help pharmacists create and deliver a successful service that meets agreed business and health benefits a need, but also creates an environment that is able to grow and is appropriate for healthcare professionals to work in.

Useful resources

Patient group directions

- Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education — Patient group direction template

- Specialist Pharmacy Service — Patient group direction template

- Specialist Pharmacy Service — Questions about signatories of patient group directions

- Specialist Pharmacy Service — To PGD or not to PGD? – that is the question: a guide to choosing the best option for individual situations

Clinical guidelines

Storage of medicines

References

[1] BBC. The changing NHS. 2013. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-19674838 (accessed December 2019)

[2] NHS. NHS long term plan. 2019. Available at: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (accessed December 2019)

[3] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. A practical guide for pharmacists in GP practices. 2019. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/ultimate-guide-and-hubs/ultimate-guide-to-working-in-a-gp-practice (accessed December 2019)

[4] Young TL. The Handbook of Project Management; a practical guide to effective policies, techniques and processes. 2nd edn. London: Kogan Page; 2008

[5] Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education. Managing projects. 2012. Available at: https://www.cppe.ac.uk/programmes/l/manproj-g-01 (accessed December 2019)

[6] Heagney J. Fundamentals of Project Management. 5th edn. New York; Amacom: 2016

[7] Edwards A & Elwyn G. Understanding risk and lessons for clinical risk communication about treatment preferences. BMJ Qual Saf 2001;10(Suppl 1):i9–i13. PMID: 11533431

[8] Langham JL. The effect of a ward-based pharmacy technician service. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2000;264(7102);961–963. URI: 20001982

[9] Carter PR. Operational productivity and performance in English NHS acute hospitals: unwarranted variations. 2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/productivity-in-nhs-hospitals (accessed December 2019)

[10] Nursing and Midwifery Council. Practising as a midwife in the UK. 2019. Available at: https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/practising-as-a-midwife-in-the-uk.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[11] Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education. A useful guide to business cases. 2019. Available at: https://www.cppe.ac.uk/programmes/l/buscase-g-01 (accessed December 2019)

[12] Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. The safe and secure handling of medicines: A team approach. 2005. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Publications/Safe%20and%20Secure%20Handling%20of%20Medicines%202005.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[13] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Professional guidance on the safe and secure handling of medicines. 2018. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/recognition/setting-professional-standards/safe-and-secure-handling-of-medicines/professional-guidance-on-the-safe-and-secure-handling-of-medicines (accessed December 2019)

[14] NHS Wales. The safe storage of medicines: cupboards. 2016. Available at: www.patientsafety.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/1104/PSN030%20Safe%20storage%20of%20medicines%20cupboards.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[15] NHS Benchmarking Network. Projects: Pharmacy and medicines optimisation. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhsbenchmarking.nhs.uk/projects/pharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation-provider-project (accessed December 2019)

[16] Wirral Globe. Midwives and parents celebrate one year since the first baby was born at Seacombe Birth Unit. 2019. Available at: https://www.wirralglobe.co.uk/news/17662748.midwives-and-parents-celebrate-one-year-since-the-first-baby-was-born-at-seacombe-birth-unit/ (accessed December 2019)