Agencja Fotograficzna Caro / Alamy Stock Photo

Effective communication with patients lies at the heart of good healthcare, is associated with increased levels of satisfaction and may improve clinical outcomes. Sensitive, honest and empathic communication may, in part, relieve the burden of difficult treatment decisions, and the physical and emotional complexities of death and dying, and lead to positive outcomes for people nearing the end of life (EoL) and their companions[1],[2],[3],[4]

. By contrast, poor communication is associated with distress and complaints[5],[6],[7],[8]

, and aggravated by resource constraints and increasing work pressures owing to an ageing population with chronic conditions and complex care needs[9]

. An emerging body of empirical work that utilises conversation analysis details the unique challenges encountered by healthcare professionals when communicating with patients nearing the EoL[10],[11],[12],[13],[14],[15],[16]

. However, the precise nature of EoL interaction in pharmacy settings is unknown — a focus on traditional counselling interactions in hospital- or community-based pharmacy[17],[18],[19],[20]

means that the explicit details of EoL discussions between pharmacists and their patients, relatives and carers has been largely undocumented.

This article focuses on the communication skills associated with the pharmacist’s extended role in palliative care, with specific reference to the skills involved in communicating with people who are approaching EoL, their families and carers. This is an increasingly relevant topic in light of pharmacists’ involvement in palliative care services both nationally and globally[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26]

.

Role of the pharmacist in palliative care

The medical needs of palliative care patients and their carers are often complex and protracted[23]

. Pharmacists’ expert pharmaceutical knowledge and broad skill set — coupled with their widespread accessibility and trusted relationships with patients and carers — mean that they are well suited to better integration within the palliative care team[22],

[25]. The pharmacist’s role is extending beyond the more traditional elements of dispensing activity and management of minor ailments towards the provision of greater psychosocial support for patients[22],[26]

. This creates opportunities for further interaction, not only with patients, but also with loved ones, relatives and carers.

Pharmacists should have a clear understanding of the unique challenges associated with palliative care-related interactions, such as ongoing assessment, clarification of clinical options where there is uncertainty, pharmacotherapeutic monitoring of the patient’s condition, as well as offering advice and support for patients, relatives and carers[25]

. Pharmacists need to be mindful that this is an emotionally difficult time for patients, relatives and carers which, for the latter two groups, may extend beyond the patient’s death and into the bereavement period. Pharmacists must, therefore, adapt their communication skills to demonstrate compassion and empathy. Moreover, they will need to work closely with the multi-disciplinary team, including the palliative care teams in outpatient, inpatient and hospice services, to ensure that patient care is not delivered in therapeutic silos, but is integrated throughout.

How pharmacists should communicate and have open discussions with the patient, carers and their families

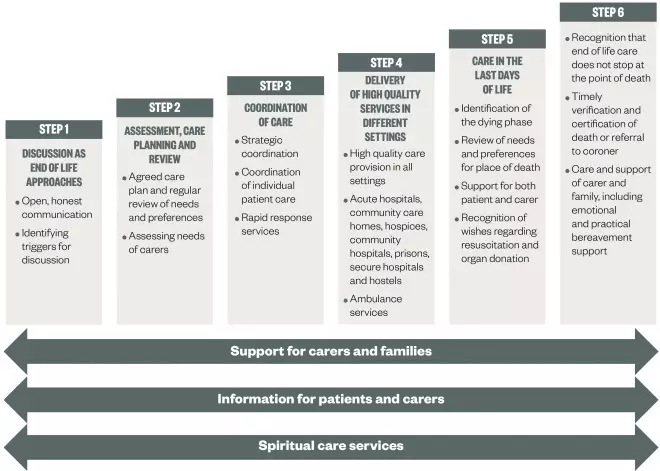

EoL is seen as the last year of a person’s life with an advanced, progressive illness or, more likely, a number of comorbidities. The government’s EoL strategy sets out its recommendations governing the six key elements that characterise the EoL pathway[27]

(see ‘Figure 1: Department of Health: End of life (EoL) care pathway’).

Figure 1: Department of Health: End of Life (EoL) care pathway

The six key elements of an EoL pathway. It is important that support for carers and families, information for patients and carers, and spiritual care services are provided alongside these steps.

The point at which discussions around EoL care are undertaken varies from person to person, but open and honest communication that is sensitive to the situation, commences early and continues through the patient’s journey, is crucial. Consistent with the key skills that are fundamental to effective communication in any clinical encounter[28]

, the aims of such discussions include:

- Eliciting the patient’s level of understanding, main problem(s) or concern(s) about their medicines (especially those that are anticipatory) and any impact (physical, emotional or social) that these are having on the patient;

- Determining how much information the patient wishes to receive and providing this to ensure medicine optimisation;

- Ascertaining whether the patient wishes more support to engage in medicine or EoL conversations with other family members or carers.

An e-learning programme produced by Health Education England for End of Life Care (e-ELCA) includes sessions focusing on communication skills development[29]

. Clinical guidance further elaborates on the skills required, including the importance of an individualised, patient-centred approach in which patients are treated respectfully, with kindness, dignity, compassion and understanding, and in which their needs, fears or concerns about EoL are listened to and discussed in a sensitive, non-judgmental manner[30]

.

Through timely identification of patients who are at risk of deteriorating and dying, and in the last year of life, healthcare professionals can tailor information and provide opportunities for patients to consider their choices for care. Patients want choices relating to seven key themes (see ‘Box 1: Patients’ preferences for choices at the end of life’)[31]

.

Box 1: Patients’ preferences for choices at the end of life (EoL)

The Department of Health ran a two-month public engagement exercise to gather people’s views on choice in EoL care, from which seven main themes emerged.

What choices are important to me at the end of life and after my death?

- I want to be cared for and die in a place of my choice;

- I want involvement in, and control over, decisions about my care;

- I want access to high quality care given by well trained staff;

- I want access to the right services when I need them;

- I want support for my physical, emotional, social and spiritual needs;

- I want the right people to know my wishes at the right time;

- I want the people who are important to me to be supported and involved in my care.

Source: Department of Health. What’s important to me: a review of choice in EoL care. London: Department of Health; 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/407244/CHOICE_REVIEW_FINAL_for_web.pdf

It may be helpful to signpost some patients to advice about drawing up an advance statement of wishes and preferences or an advance decision to refuse treatment, or to information about how to appoint someone with a lasting power of attorney (LPA) should they lose capacity to make their own decisions (see

‘Additional resources’

).

Pharmacists will also need to develop strategies for supporting the patient’s relatives or carers, who may be involved in enabling the patient to make choices or communicate their wishes. General Medical Council (GMC) guidance states that family members may be directly involved in the patient’s treatment or care, and in need of relevant information to help them care for, recognise and respond to changes in the patient’s condition[32]

. In cases where patients may lack capacity, pharmacists can facilitate talk about the patient’s likely wishes, beliefs and values regarding treatment. However, pharmacists will need to be skilful to ensure that relatives or carers do not think themselves, or have the burden of being, the decision-maker if they lack the delegated authority of an attorney (LPA).

In a summary of evidence-based techniques for communicating with patients and family members, LeBlanc and Tulsky identify core communication strategies that include[33]

:

- Using open-ended questions;

- Soliciting agendas early in the interaction;

- Asking permission to raise particular topics;

- Using verbal and non-verbal expressions of empathy;

- Using praise;

- Using ‘wish’ statements;

- Aligning with the hopes of patients, loved ones and carers through the use of ‘hope for the best’ phraseology.

Explaining clinical options, and risks and benefits

Patients with advanced illness are usually receiving complicated treatment regimes consisting of multiple doses of medicines and formulations. Pharmacists will need to explore the best ways to communicate such information, especially where the patient’s first language is not English, the patient is a child, or the patient is suffering from a condition that reduces their cognitive function. Such communication might need to involve supplementing written information with symbols or visual images (e.g. pictures of tablets), using jargon-free explanations, as well as providing options for regular contact.

When discussing treatments, pharmacists should: help patients (and relatives or carers) understand the purpose of a medicine and how it is optimally used; elicit and answer questions; discuss the risks, benefits and consequences of treatments; minimise side effects and maximise safety; allay fears about opioid medications and their use; offer adherence strategies (e.g. dosette boxes) and strategies to reduce stress (e.g. prescription collection and delivery); and review medications to highlight potential interactions and those that may no longer be of value.

When discussing the risks and benefits of treatment and the use of strong opioids, pharmacists should be aware of the recommendations and strategies in current clinical guidance[30],[34]

(see boxes 2 and 3).

Box 2: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical guideline [CG138]. Patient experience in adult NHS services: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS services

Enabling patients to actively participate in their care: shared decision-making

1.5.24 When offering any investigations or treatments:

- Personalise risks and benefits as far as possible;

- Use absolute risk rather than relative risk (for example, the risk of an event increases from 1 in 1000 to 2 in 1000, rather than the risk of the event doubles);

- Use natural frequency (for example, 10 in 100) rather than a percentage (10%);

- Be consistent in the use of data (for example, use the same denominator when comparing risk: 7 in 100 for one risk and 20 in 100 for another, rather than 1 in 14 and 1 in 5);

- Present a risk over a defined period of time (months or years) if appropriate (for example, if 100 people are treated for 1 year, 10 will experience a given side effect);

- Include both positive and negative framing (for example, treatment will be successful for 97 out of 100 patients and unsuccessful for 3 out of 100 patients);

- Be aware that different people interpret terms such as rare, unusual and common in different ways, and use numerical data if available;

- Think about using a mixture of numerical and pictorial formats (for example, numerical rates and pictograms).

Source: Reproduced with permission of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg138/chapter/1-guidance

Box 3: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical Guideline [CG140]. Palliative care for adults: strong opioids for pain relief

Recommendations: communication

1.1.1 When offering pain treatment with strong opioids to a patient with advanced and progressive disease, ask them about concerns such as:

- Addiction;

- Tolerance;

- Side effects;

- Fears that treatment implies the final stages of life.

1.1.2 Provide verbal and written information on strong opioid treatment to patients and carers, including the following:

- When and why strong opioids are used to treat pain;

- How effective they are likely to be;

- Taking strong opioids for background and breakthrough pain, addressing:

- How, when and how often to take strong opioids;

- How long pain relief should last.

- Side effects and signs of toxicity;

- Safe storage;

- Follow-up and further prescribing;

- Information on who to contact out of hours, particularly during initiation of treatment.

1.1.3 Offer patients access to frequent review of pain control and side effects.

Source: Reproduced with permission of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg140/chapter/1-recommendations

Managing patients who are not emotionally ready to discuss their future care

Patients with advanced illness are often required to make complex decisions about treatment and care that may require consideration of risks and benefits, or decisions about whether a particular course of action should be discontinued. GMC guidance advises healthcare professionals to ensure that patients have opportunities to discuss the options available to them and what treatment (or refusal) is likely to involve[32]

. While some patients will be able to engage in EoL discussions, others may be less willing to think about future issues or may find the prospect of thinking about deterioration and dying too distressing. All healthcare professionals and pharmacists will find it challenging to engage such patients in discussion about future treatment and ‘what if?’ scenarios. Pharmacists will need to develop strategies that enable them to deal with these discussions. As recent research has shown, this requires skilful techniques that rely on the patient’s use of verbal or non-verbal cues in order to explore the concerns of patients, their relatives or carers in ways that allow patients to raise EoL considerations when they are ready[16]

. Where patients wish to nominate a relative or carer to have these discussions, it is important to support their wishes and establish their consent.

Managing expectations among patients, relatives and carers

Particular difficulties may arise in settings where families or carers are involved in planning ongoing care, such as in the event of a loss of capacity or in cases where treatment options for children or young people need to be discussed. The stresses associated with life-limiting and life-threatening illness can give rise to differing opinions over treatment options that can have implications for the quality of care (e.g. misunderstanding prognosis, advice and clarity over when to administer anticipatory medicines)[33]

. Managing expectations or disagreements takes time, and patients, their families and carers will need support to arrive at important decisions. Advice for recognising, acknowledging and managing divergent views and potential conflict has been suggested[33]

as a useful negotiating strategy in working towards a consensus[29]

.

Managing uncertainty: hoping for the best but preparing for the worst

For an individual patient, the likely benefits and harms of palliative treatments aimed at maintaining disease stability, slowing deterioration or reducing symptoms are uncertain. While research may provide pharmacists with medical information about the number needed to treat or number needed to harm to achieve a defined outcome for the individual patient, this is unpredictable. Enabling patients to appreciate this uncertainty, while supporting their need for hope, is a tricky communication task and professionals, in their communication and relationships with patients, can enhance or diminish their sense of hope[35]

(see ‘Box 4: Contrasting communication behaviours’).

Box 4: Contrasting communication behaviours

Communication behaviours that contribute to a patient’s sense of hope:

- Being present and taking time to talk;

- Giving information in a sensitive, compassionate manner;

- Answering questions;

- Being nice, friendly and polite.

Behaviours that have a negative influence on hope:

- Giving information in a cold way;

- Being mean or disrespectful;

- Having conflicting information from professionals.

Behaviours that demonstrate the valuing of patients as individuals and the enormity of their life situation can really help. These behaviours are not simply ‘being nice’. They are important therapeutic interventions that promote a sense of hope and preserve a sense of dignity, something that many patients fear the loss of[36]

.

While a focus on unrealistic hopes (e.g. cure or more time) may not be helpful, a balance of hoping for a realistic best (e.g. that the pain will go away with this treatment), while preparing for deterioration (e.g. “what we will do if this isn’t sufficient is…”), is the best strategy[37],[38],[39]

.

Understanding and respect for cultural, religious or spiritual beliefs

A person’s culture, religious or spiritual beliefs provides them with a framework and ideas about health and illness, through which healthcare decisions are made.

Pharmacists need cultural competence to ensure treatment is aligned with these preferences and wishes. They can achieve this through seeking clarification from patients and family about aspects of their care that may be influenced by their cultural, religious or spiritual beliefs. Consider, for example, asking the patient about:

- Faith: What is important to them? What rituals, books or places for prayer/meditation do they need?

- Diet: Are there any preferred foods or foods that are considered taboo? (e.g. gelatin in some capsules is not appropriate for vegetarians, and pork is not considered halal in Islam).

- Touch and respect: Consider any issues that gender differences may provoke. Would the patient like to discuss matters alone or with someone else present?

It can be helpful to have insight into traditional practices of different faiths and how this influences dying and bereavement. Several useful sessions about working with cultural diversity can be found in the e-learning for End of Life Care (e-ELCA) programme[29]

. Public Health England have recently produced a guide for healthcare professionals working with diverse communities[29]

.

Recognising the changing needs of the patient and those close to them

As patients become sicker, their needs and those of their companions increase. Pharmacists can make a huge difference to the stress and satisfaction that families experience by offering practical support. Strategies that anticipate needs and offer solutions are appreciated. Remaining professional but also demonstrating understanding and compassion can help families who can sometimes find it more difficult to cope with their emotions when people are ‘too nice’ (e.g. asking them how they are). For example:

- Would it help if I put the tablets for each time and day in an easy to remember pack?

- I can make an arrangement for the GP to send prescriptions directly to me if that helps you? I can dispose of the old medicines if you can bring them in.

Effective communication with patients is central to the goal of medicines optimisation. Following often simple strategies and techniques on how to manage difficult situations will improve pharmacists’ confidence and ensure patients’, carers’ and families’ medicine needs at the EoL are fully acknowledged and met.

Additional resources:

- NHS. Health Education England. e-Learning for End of Life Care (e-ELCA)

- NHS Choices. Planning ahead for the end of life

- NHS. Improving Quality. Planning for your future care – a guide

- Public Health England. Faith at end of life: a resource for professionals, providers and commissioners working in communities

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE guideline [NG31]. Care of dying adults in the last days of life

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Neuberger J, Guthrie C, Aaronovitch D et al. More care, less pathway: a review of the Liverpool care pathway. London: Department of Health; 2013. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/212450/Liverpool_Care_Pathway.pdf (accessed January 2017)

[2] Royal College of General Practitioners, Royal College of Nursing. End of life care patient charter – a charter for the care of people who are nearing the end of their life. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, Royal College of Nursing; 2011. Available at: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical/clinical-resources/~/media/Files/CIRC/CIRC_EOLCPatientCharter.ashx (accessed January 2017)

[3] Levin T & Weiner JS. End-of-life communication training. In: Kissane DW, Bultz BD, Butow PN, Finlay IG, editors. Handbook of communication in oncology and palliative care. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010

[4] Kissane D, Bultz B, Butow P et al. Handbook of communication in oncology and palliative care. Oxford: OUP; 2011

[5] Moore PM, Rivera Mercado S, Grez Artigues M et al. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(3):CD003751. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003751.pub3

[6] Jackson A, Purkis J, Burnham E et al.Views of relatives, carers and staff on end of life care pathways. Emerg Nurse. 2010;17(10):22–26. doi: 10.7748/en2010.03.17.10.22.c7616

[7] Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Enquiry. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Enquiry. Francis R, editor. London: Stationery Office; 2013. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/279124/0947.pdf (accessed January 2017)

[8] Magnus D, Fox E, Elster N et al. Dying without dignity – investigations by the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman into complaints about end of life care. London: Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman; 2015

[9] World Health Organization: Europe. Palliative care: the solid facts. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization; 2004. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/98418/E82931.pdf (accessed January 2017)

[10] Peräkylä A. AIDS counselling: institutional interaction and clinical practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pess; 1995

[11] Lutfey K & Maynard DW. Bad news in oncology: how physician and patient talk about death and dying without using those words. Soc Psychol Q. 1998;61(4):321–341. doi: 10.2307/2787033

[12] Clemente I. Uncertain future: communication and culture in childhood cancer treatment. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2015

[13] Beach WA & Dozier DM. Fears, uncertainties, and hopes: patient-initiated actions and doctors’ responses during oncology interviews. J Health Commun. 2015;20(11):1243–1254. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018644

[14] Shaw C, Chrysikou V, Davis S, Gessler S, Rodin G, Lanceley A. Inviting end-of-life talk in initial CALM therapy sessions: a conversation analytic study. Patient Educ Couns. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.08.024

[15] Maynard DW, Cortez D & Campbell TC. ‘End of life’ conversations, appreciation sequences, and the interaction order in cancer clinics. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(1):92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.07.015

[16] Pino M, Parry R, Land V et al. Engaging terminally ill patients in end of life talk: how experienced palliative medicine doctors navigate the dilemma of promoting discussions about dying. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0156174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156174

[17] Pilnick A. “Patient counselling” by pharmacists: advice, information, or instruction? Sociol Q. 1999;40(4):613–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.1999.tb00570.x

[18] Pilnick A. “Patient counselling” by pharmacists: four approaches to the delivery of counselling sequences and their interactional reception. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(4):835–849. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00082-5

[19] Nguyen HT. Constructing ‘expertness’: a novice pharmacist’s development of interactional competence in patient consultations. Commun Med. 2006;3(2):147–160. doi: 10.1515/CAM.2006.017

[20] Nguyen HT. Developing interactional competence: a conversation-analytic study of patient consultations in pharmacy. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan; 2012.

[21] Atayee RS, Best BM & Daniels CE. Development of an ambulatory palliative care pharmacist practice. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(8):1077–1082. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0023

[22] O’Connor M, Fisher C, French L et al. Exploring the community pharmacist’s role in palliative care: focusing on the person not just the prescription. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(3):458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.04.037

[23] Austwick E & Brooks D. The role of the pharmacist as a member of the palliative care team. Prog Palliat Care. 2013;11(6):315–320. doi: 10.1179/096992603225003752

[24] Cortis LJ, McKinnon RA & Anderson C. Palliative care is everyone’s business, including pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(2):21. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77221

[25] Walker KA. Role of the pharmacist in palliative care. Prog Palliat Care. 2013;18(3):132–139. doi: 10.1179/096992610x12624290276755

[26] Thoma J, Zelko R & Hanko B. The need for community pharmacists in oncology outpatient care: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(4):855–862. doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0297-2

[27] Department of Health. End of life care strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: Department of Health; 2008. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/136431/End_of_life_strategy.pdf (accessed January 2017)

[28] Maguire P & Pitceathly C. Key communication skills and how to acquire them. BMJ 2002;325:697–700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7366.697

[29] NHS. Health Education England. e-End of Life Care for All (e-ELCA). Available at: http://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/end-of-life-care/ (accessed January 2017)

[30] National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Patient experience in adult NHS services: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS services. NICE clinical guideline 138. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2012. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg138 (accessed January 2017)

[31] Department of Health. What’s important to me: a review of choice in end of life care. London: Department of Health; 2015. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/407244/CHOICE_REVIEW_FINAL_for_web.pdf (accessed January 2017)

[32] General Medical Council (GMC). Treatment and care towards the end of life: good practice in decision making. London: General Medical Council; 2010. Available at: http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/end_of_life_care.asp (accessed January 2017)

[33] LeBlanc TW & Tulsky JA. Communication with the patient and family. In: Cherny N, Fallon M, Kaasa S, Portenoy RK, Currow DC, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 5th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015. p. 337–344.

[34] National Collaborating Centre for Cancer. Opioids in palliative care: safe and effective prescribing of strong opioids for pain in palliative care of adults. NICE clinical guideline 140. Cardiff: National Collaborating Centre for Cancer; 2012. [updated May 2012]. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK115251/ (accessed Janaury 2017)

[35] Koopmeiners L, Post-White J, Gutknecht S et al. How healthcare professionals contribute to hope in patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1997;24(9):1507–1513. PMID: 9348591

[36] Chochinov HM. Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. BMJ 2007;335(7612):184–187. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39244.650926.47

[37] Back AL, Arnold RM, Quill TE. Hope for the best, and prepare for the worst. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(5):439–443. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-5-200303040-00028

[38] Feuz C. Hoping for the best while preparing for the worst: a literature review of the role of hope in palliative cancer patients. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2012;43(3):168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2011.10.002

[39] Kahana B, Kahana E, Lovegreen L & Brown J. Hoping for the best and preparing for the worst: end-of-life attitudes of the elderly. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2011;1(93). doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000053.94

You might also be interested in…

Government to ‘strengthen’ out-of-hours support for palliative care services

Support for pharmacies providing palliative care urged as hospices get cash injection