Science Photo Library

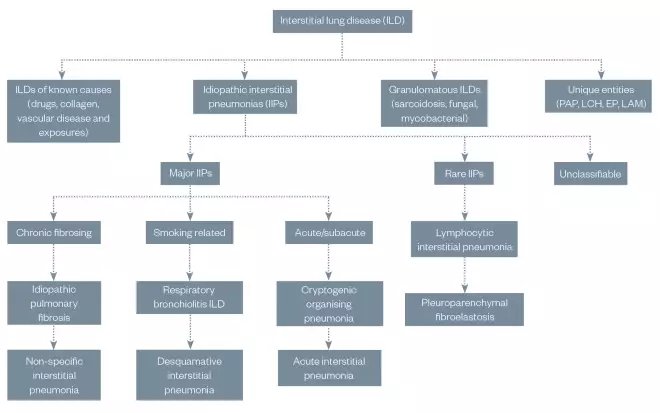

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) describes a diverse group of lung diseases that result in the impairment or fibrosis of the alveolar interstitium. They can be classified according to clinical, radiological, physiological or pathological criteria (see Figure 1)[1]

. Around two-thirds of ILDs have no known cause; the remainder are caused by environmental or occupational factors, infection or drug toxicity. The management of the ILD subtypes differs; therefore, accurate diagnosis and therapy often requires specialist input from a multidisciplinary team, which may include a chest physician, rheumatologist, radiologist and histopathologist, as well as a specialist nurse and pharmacist[2],[3],[4]

.

Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias are the most common ILDs and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) has the greatest prevalence within this cohort of patients. IPF is defined by The American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society as “a specific form of chronic, progressive fibrosing interstitial pneumonia of unknown cause, occurring in adults”, and is characterised by progressive worsening of breathlessness and lung function decline, associated with a poor prognosis. IPF is defined by the radiological and/or histopathological pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP)[1]

.

The increasing rate of hospital admissions and deaths owing to IPF suggests the burden of disease is rising. Around 5 million people worldwide are reported as having IPF and it is estimated that a further 5,000 patients will be diagnosed with IPF each year. In the UK, the median survival time is three years after diagnosis[4]

; however, 20% of people with IPF survive for more than five years[2],[3]

,[4]

. IPF is often initially misdiagnosed as COPD or congestive heart failure and disease progression varies over time and between patients. There is currently no cure for IPF; therefore, early recognition and accurate diagnosis are likely to improve outcomes through avoidance of potentially harmful therapies and by prompting initiation of effective medicines and supportive care[2],[3]

,[4]

.

Figure 1: General overview of the classification of interstitial lung disease

Presentation of interstitial lung diseases are broadly similar (i.e. dyspnoea, desaturation, fatigue, restrictive pattern of spirometry or chronic cough) and differentiation is difficult, hence the need for an appropriate multidisciplinary team approach to diagnosis and management.

EP: eosinophilic pneumonia; LAM: lymphangioleiomyomatosis; LCH: Langerhans cell histiocytosis; PAP: pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

Data taken from Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM et al. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5803655/

This article describes the evidence base for IPF diagnosis and management, and the role that pharmacists can play as part of a multidisciplinary team.

Pathogenesis

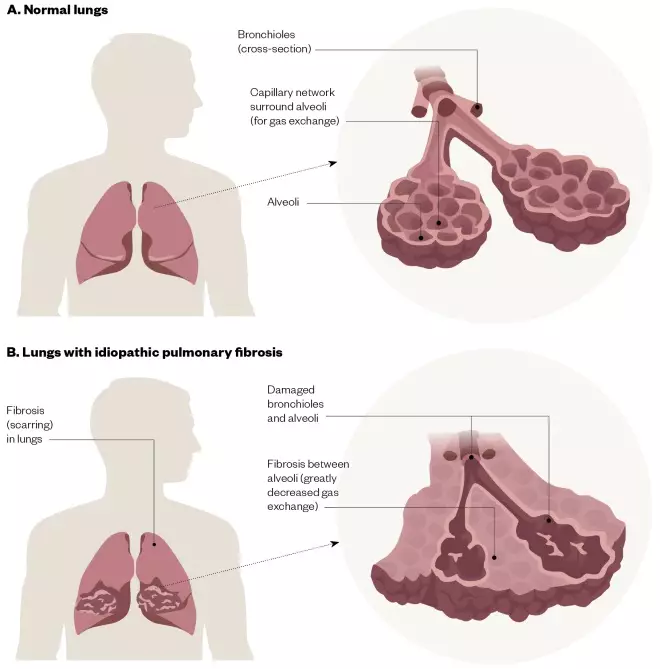

The exact pathogenesis of IPF is unknown; it is currently thought to involve repetitive injury and abnormal wound healing in alveolar epithelium, which results in the deposition of interstitial fibrosis by myofibroblasts, leading to progressive lung injury, scarring and irreversible loss of function (see Figure 2)[5]

. Injury can lead to the activation of coagulation cascades, oxidant pathways, fibrocytes and circulating cells, as well as macrophage stimulation.

Epithelial tissue usually responds to injury through a sequence of highly regulated, overlapping events for successful tissue repair and barrier integrity. When the normal responses to tissue injury become dysregulated (e.g. shortened telomeres, oxidative injury, proteostatic dysregulation and mitochondrial dysfunction), the imbalance of profibrotic mediators (e.g. transforming growth factor beta-1, vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], fibroblast growth factor [FGF] and platelet-derived growth factor [PDGF]) and antifibrotic mediators (e.g. prostaglandin E2) may contribute to the replacement of functional tissue with fibrous scar tissue[2],[3]

,[6]

.

Figure 2: Lungs with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

The difference between (A) normal lungs and (B) lungs with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which show damaged bronchioles, alveoli and fibrosis, leading to reduced gas exchange.

Risk factors

Although it is not known what factors directly cause IPF, there are several inherited and environmental factors that have been linked with an increased risk of developing IPF. These include:

- A family history of ILD;

- Cigarette smoking;

- Exposure to certain types of dust (e.g. metal and wood dust)[7]

; - Comorbidities, such as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)[7]

.

Abnormal gastro-oesophageal reflux has been observed in 90% of patients with IPF and it has been suggested that GORD can cause or worsen IPF.

In addition, a genetic risk factor has been identified. Mucin 5B (MUC5B) is a glycoprotein required for airway clearance and innate immune responses to bacteria; it is now thought a polymorphism in MUC5B substantially increases the risk of IPF.

Furthermore, IPF is more common in male patients aged over 60 years[2],[3]

,[4]

,[6]

.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of IPF include persistent, dry and irritating cough; dyspnoea that can affect the ability to eat or talk; fatigue; rounded and swollen fingertips (known as ‘finger clubbing’); and loss of appetite and subsequent gradual weight loss. Symptoms of IPF often affect the patient’s quality of life (QOL); continuous coughing can be painful and disruptive, and fatigue and dyspnoea can limit daily activities. As a result, IPF can lead to feelings of fear, anxiety, isolation, depression and anger[2],[3]

,[4]

.

A small number of patients with IPF — around 5–10% per year — may experience unpredictable and substantial worsening of the disease, known as an acute exacerbation. Acute exacerbations can increase the burden of disease, reduce QOL and contribute to disease progression. They can also be fatal; 50% of patients hospitalised for acute exacerbation of IPF die during hospitalisation. The diagnosis and management of acute exacerbations varies widely owing to limited evidence upon which to base recommendations. This continues to be an area of active research[1]

,[8],[9],[10]

.

Diagnosis

Accurate diagnosis of IPF is challenging owing to its complex, heterogeneous nature, as well as the difficulty in differentiating it from other diseases with similar clinical symptoms, and radiological and histopathological patterns.

In patients aged over 45 years, IPF should be considered in those who present with the following criteria: unexplained chronic dyspnoea on exertion; persistent cough; bibasilar inspiratory crackles on auscultation (often described as ‘Velcro-like’); and/or finger clubbing. Spirometry results can appear normal or impaired with a restrictive pattern, which sometimes can be obstructive.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that people with suspected IPF should be assessed with all of the following[4]

:

- Taking a detailed history, clinical examination and blood tests to help exclude alternative diagnoses;

- Spirometry and gas transfer;

- Chest x-ray;

- High-resolution computed tomography scan.

Diagnosis can only be made using these clinical features, lung function and radiological findings, with the consensus of the multidisplinary team[4]

. These features are sufficient to allow a confident diagnosis of IPF in more than 50% of suspected cases. If the multidisciplinary team cannot make a confident diagnosis from these findings, a biopsy can be considered[4]

. However, biopsy is associated with mortality within 30 days after the procedure, with a reported frequency of 3–17%. This mortality risk is increased in patients with idiopathic UIP who present with atypical features (any computed tomography features and/or distribution of lung fibrosis that do not suggest any specific aetiology)[2]

.

Table 1 summarises the potential investigations recommended in national and international guidelines that may be undertaken to arrive at a diagnosis of IPF.

| Investigation | Description |

|---|---|

| History | Document and discuss a detailed history of symptoms with the patient and/or carer (with permission). If interstitial lung disease (ILD) is suspected, question further to identify causative factors, such as pets (including birds); occupation (e.g. exposure to livestock); environment (e.g. exposure to mould); smoking history; and drug toxicity. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) should be considered in patients aged over 45 years with persistent breathlessness (initially on exertion); persistent dry cough; fatigue; weight loss and/or appetite loss. |

| Physical examination | Bibasilar inspiratory crackles on auscultation (also described as ‘Velcro-like’) could support a diagnosis of IPF. Finger clubbing may be observed in patients with IPF. |

| Lung function tests | Spirometry and lung volumes may be normal in early ILD or with co-existing emphysema. Impaired spirometry with a restrictive (or in some cases, obstructive) pattern may be observed with reduced values for forced vital capacity, total lung capacity and carbon monoxide diffusing capacity of the lung. Resting hypoxaemia and/or exertional desaturation is also observed in IPF. |

| Chest radiography | This is usually normal or non-specific in early disease. Bilateral reticular infiltrates, hazy opacities and reduced inspiratory lung volumes should prompt an investigation for ILD. |

| High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) | HRCT features frequently seen in usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) include honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis and traction bronchiolectasis, which may be seen with the concurrent presence of ground-glass opacification and fine reticulation. Four levels of confidence have been proposed based on the presence and/or absence of specific features[2]

|

| Blood tests | Consider autoimmune screen to identify any autoimmune conditions. |

| Lung biopsy | For patients with suspected IPF without a definite UIP pattern on HRCT, The American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) guidelines recommend histopathological analysis of a surgical lung biopsy. Owing to the risk of serious complications, surgical lung biopsies are only undertaken when the outcome is likely to affect management. Histopathological features frequently observed in IPF include dense fibrosis with architectural distortion; predominant subpleural and/or paraseptal distribution of fibrosis; patchy involvement of lung parenchyma by fibrosis; fibroblastic foci; and the absence of features to suggest alternative diagnosis. Four levels of confidence have been proposed based on the presence and/or absence of specific histological features:

|

Source: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198(5):e44–e68[2] | |

The timely and accurate diagnosis of IPF is important to ensure that patients gain access to appropriate clinical services and therapy for better relief of symptoms, which will help slow disease progression and improve clinical outcomes. As a result, if suspected, the patient should be referred for specialist assessments and diagnosis as soon as possible[2],[3]

,[12]

.

Management

IPF is a chronic, progressive and irreversible condition. The major goal of IPF management is to slow the decline in lung function and to reduce the frequency and severity of acute exacerbations.

Pharmacological therapy

There are currently two antifibrotic medicines, pirfenidone[13]

and nintedanib[14]

, licensed for use in the UK and approved by NICE in patients with forced vital capacity (FVC) between 50% and 80% predicted.

Drug selection

Although the mechanism of action is not fully understood, it is thought that pirfenidone attenuates fibroblast proliferation and inhibits the synthesis and activity of TGF-α and -β, which are potent mediators that promote the formation of fibrotic tissues.

Nintedanib is a potent intracellular inhibitor of tyrosine kinases that targets multiple growth receptors (e.g. PDGF-α and -β; VEGF 1, 2 and 3; and FGF 1, 2 and 3) to slow down disease progression[3]

,[4]

.

Pirfenidone and nintedanib have been evaluated in multiple clinical trials. A summary of a selection of these trials are described in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. As yet, there are little data on the comparison of these medicines and which, if any, should be first line.

| Trial | CAPACITY 004 | CAPACITY 006 | ASCEND |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Phase III, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. | Phase III, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. | Phase III, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. |

| Number of patients | 435 | 344 | 555 |

| Intervention | Pirfenidone (2,403mg per day); or Pirfenidone (1,197mg per day); or Placebo. | Pirfenidone (2,403mg per day); or Placebo. | Pirfenidone (2,403mg per day); or Placebo. |

| Selection criteria | Patients aged 40–80 years with a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Other criteria included a range of 50–90% of the predicted forced vital capacity (FVC), a range of 35–90% of the predicted carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) and a 6-minute walk distance of 150m. | Patients aged 40–80 years with a diagnosis of IPF. Other criteria included a range of 50–90% of the predicted FVC, a range of 35–90% of the predicted DLCO and a 6-minute walk distance of 150m. | Patients aged 40–80 years with a diagnosis of IPF (confirmed on definite or possible usual interstitial pneumonia pattern on a high-resolution computed tomography scan). Other criteria included a range of 50–90% of the predicted FVC, a range of 30–90% of the predicted DLCO, a ratio of the forced expiratory volume in 1 second to the FVC of 0.80 or more, and a 6-minute walk distance of 150m. |

| End points | The primary end point was a change in predicted FVC at week 72 (this was met only for CAPACITY 004). The secondary end points were the change from baseline to week 52 in the 6-minute walk test and progression-free survival (defined as decrease of 10% in predicted FVC, 50m in the 6-minute walk test, or death). | The primary end point was the change in FVC or death at week 52. The secondary end points were the change from baseline to week 52 in the 6-minute walk test and progression-free survival (defined as decrease of 10% in predicted FVC, ≥50m in the 6-minute walk test, or death). | |

| Outcome | A reduction in FVC decline was demonstrated in those prescribed pirfenidone (2,403mg per day over 72 weeks). Increased rates of nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting, anorexia, photosensitivity and rash were observed in patients prescribed pirfenidone. | No significant benefit was observed. Increased rates of nausea, dyspepsia, vomiting, anorexia, photosensitivity and rash were observed in patients prescribed pirfenidone. | Pirfenidone significantly reduced the proportion of patients who had a more than 10% decline in their FVC during the 52-week follow-up. Mortality or breathlessness scores did not differ. Pooled analysis suggested reduced mortality with pirfenidone and increased rate of photosensitivity, fatigue, stomach discomfort and anorexia. |

Source: Lancet 377(9779):1760–1769[15] | |||

| Trial | TOMORROW | INPULSIS-1 | INPULSIS-2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Phase IIb randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. | Phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. | Phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. |

| Number of patients | 428 | 513 | 548 |

| Intervention | Nintedanib 50mg per day; or Nintedanib 100mg per day; or Nintedanib 150mg per day; or Nintedanib 150mg twice daily; or Placebo. | Nintedanib 150mg twice daily; or Placebo. | Nintedanib 150mg twice daily; or Placebo. |

| Selection criteria | Aged over 40 years. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). | Aged over 40 years. Diagnosis of IPF within the previous five years. Forced vital capacity (FVC) 50% or more of the predicted value, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide 30–79% of the predicted value, and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest within the previous 12 months (including probable usual interstitial pneumonia [UIP] in addition to definite UIP). Concomitant therapy with up to 15mg of prednisone per day, or the equivalent was permitted if the dose had been stable for eight or more weeks before screening. | Aged over 40 years. Diagnosis of IPF within the previous five years. FVC 50% or more of the predicted value, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide 30–79% of the predicted value, and HRCT of the chest within the previous 12 months (including probable UIP in addition to definite UIP). Concomitant therapy with up to 15mg of prednisone per day, or the equivalent was permitted if the dose had been stable for eight or more weeks before screening. |

| End points | The primary end point was the rate of decline in FVC at week 52. The econdary end points were change in carbon monoxide diffusing capacity, 6-minute walk distance, ratio of the forced expiratory volume in 1 second to the FVC, MRC dyspnoea scale score and St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) at 52 weeks. Occurrences of IPF exacerbations and survival were also included. | The primary end point was the annual rate of decline in FVC; this was significantly reduced on therapy. The secondary end points were the time to first acute exacerbation and the change from baseline in the total score on the SGRQ. | The primary end point was the annual rate of decline in FVC; this was significantly reduced on therapy. The secondary end points were time to the first acute exacerbation and the change from baseline in the total score on the SGRQ. |

| Outcome | No significant difference was observed between groups in mortality. A lower percentage of patients had an FVC decline of more than 10% during 12-month follow-up when on nintedanib 150mg twice daily, compared with all other groups. Fewer acute exacerbations were observed in nintedanib groups. | No significant benefit in quality of life, acute exacerbation rate or mortality. There was a significant increase in the incidence of adverse effects, such as diarrhoea, vomiting and nausea, and elevated liver enzymes were observed. A higher percentage of patients in the nintedanib groups had myocardial infarctions. Pooled analysis suggested reduction in acute exacerbations on nintedanib compared with placebo by around 50%. | No significant benefit in quality of life, acute exacerbation rate or mortality. There was a significant increase in incidence of adverse effects, such as diarrhoea, vomiting and nausea, and elevated liver enzymes were observed. A higher percentage of patients in the nintedanib groups had myocardial infarctions. Pooled analysis suggested reduction in acute exacerbations on nintedanib compared with placebo by around 50%. |

Source: N Engl J Med 2014;370(22):2071–2082[17] | |||

Cautions and contraindications

Pirfenidone is cautioned for use in mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment (i.e. patients graded as Child-Pugh A and B) and contraindicated in severe hepatic impairment and end-stage disease. It is also cautioned in moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance 30–50ml/min) and contraindicated in severe renal impairment and end-stage kidney disease. Other contraindications include hypersensitivity to pirfenidone, history of angioedema with pirfenidone and concomitant use of fluvoxamine.

Nintedanib is cautioned for use in mild hepatic impairment (i.e. patients graded as Child-Pugh A), with a recommendation to prescribe a lower dose of 100mg twice daily. It is not recommended for use in moderate-to-severe (i.e. patients graded as Child-Pugh B and C) hepatic impairment. Nintedanib is contraindicated for use in patients with hypersensitivity to the drug, peanuts, soya or any of the excipients. It should be used with caution, if at all, in patients with higher bleeding or cardiovascular risk (including coronary artery disease); higher rates of bleeding and myocardial infarction were observed in the treatment arms of the INPULSIS studies. In addition, the concomitant use with anticoagulant and prothrombotic drugs was not studied in the INPULSIS trials and should be avoided where possible[18],[19]

.

Cautions and contraindications should be considered carefully and, where possible, patients should be given the opportunity to make an informed decision about antifibrotic therapy.

Dosage

Pirfenidone should be titrated up over 14 days: 267mg three times daily for 7 days, followed by an increase to 534mg three times daily after 7 days, if tolerated. This is then further increased to a target dose of 801mg three times daily after 7 days, if tolerated.

Nintedanib should be prescribed at a dose of 150mg twice daily and the doses should be taken 12 hours apart.

Pirfenidone and nintedanib should be taken with food[18],[19]

,[20],[21]

.

Adverse effects

As drug treatment can delay disease progression and reduce mortality risk, it is important that any adverse effects are prevented and/or managed effectively so patients can continue on therapy (see Table 4 and Table 5). When necessary, dose reductions or treatment interruption can be considered to manage adverse effects and, once symptoms have resolved or become tolerable, the recommended daily dose can be re-introduced, if tolerated.

Nintedanib is listed as a black triangle; therefore, any incidence of adverse effects need to be assessed for severity and reported via the Yellow Card Scheme[20],[21]

.

| Adverse effect | Supportive therapy | Dose adjustment | Supportive management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea and vomiting | Ensure pirfenidone is taken with a glass of water and food, and that adequate hydration is maintained. Consider use of antiemetics (e.g. metoclopramide 10mg three times daily). | Consider interruption of therapy or reduction of dose if symptomatic relief is ineffective. Consider restarting therapy at a reduced or full dose, if appropriate. | Avoid eating big meals; avoid eating in warm rooms; avoid eating fried, greasy or spicy foods; avoid drinking liquids with meals and carbonated drinks; avoid strong odours (e.g. cooking smells, smoke, or perfume). |

| Liver enzyme elevations | Check for clinical signs and symptoms of liver injury (e.g. jaundice). | If clinical signs and symptoms of liver injury are present or hyperbilirubinaemia is observed, discontinue pirfenidone. If liver transaminases are increased five times above the normal upper limit, discontinue. | Monitor liver profile, clinical signs and symptoms of liver injury. |

| Severe skin reaction to sunlight (i.e. blistering and/or peeling) | Recommend the patient to use sun block SPF 50+ every day (especially in peak UV hours [10:00–16:00]). | If mild-to-moderate photosensitivity reaction or rash occurs, patients should be reminded to use sun block and avoid exposure to the sun. Pirfenidone dose can be reduced to 267mg three times daily. If the reaction or rash persists after 7 days, hold therapy for 15 days and re-titrate when resolved. If severe photosensitivity reaction or rash occurs, hold pirfenidone and seek medical advice. Re-titrate when resolved. | Avoid sun exposure and exposure to sun lamps/artificial sun. Cover the skin when outdoors with a full-sleeve shirt and hat. Avoid other medicines known to cause photosensitivity. |

| Dizziness and fatigue | Patients should be aware of these potential adverse effects and to review their reaction to pirfenidone before driving or operating heavy machinery. | Consider reduction of dose or interruption of therapy if dizziness and fatigue persist. | Patients with fatigue should be referred to pulmonary rehabilitation and encouraged to exercise. |

| Appetite/weight loss | Appetite and weight should be monitored regularly. | Consider reducing the dose of pirfenidone if the recommended dose is no longer tolerated. | Provide dietary advice to increase calorific intake. Consider referral to a dietitian. |

Source: EMC[18] | |||

| Adverse effect | Supportive therapy | Dose adjustment | Supportive management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhoea | Maintain adequate hydration. Loperamide 4mg immediately and then 2mg after each loose stool (up to 16mg per 24 hours). | Consider interruption of therapy or reduction of dose to 100mg twice daily if symptomatic relief is ineffective. Consider restarting therapy at a reduced dose or full dose, if appropriate. Discontinue nintedanib if severe diarrhoea persists, despite dose reduction. | Avoid eating big meals; avoid fried, greasy, or spicy foods; avoid high-fibre foods; avoid coffee, tea, alcohol, and sweet foods and drinks; avoid milk/milk products if they make diarrhoea worse. |

| Liver enzyme elevations | Measure aminotransferases at baseline (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate transaminase, bilirubin) then monthly for three months and then periodically thereafter. Check for clinical signs and symptoms of liver injury (e.g. jaundice). | If liver transaminase levels are raised above three times the upper limit of normal, consider dose reduction or interruption until levels return to normal. Check for signs of drug-induced liver injury. If there are no clinical signs, re-introduce nintedanib at a reduced or normal dose. If clinical signs and symptoms of liver injury (e.g. jaundice) are present, discontinue nintedanib. | Monitor liver profile, as well as clinical signs and symptoms of liver injury. |

| Appetite/weight loss | Regularly monitor appetite and weight. | Consider reducing the dose of nintedanib if the recommended dose is no longer tolerated. | Provide dietary advice to increase calorific intake. Consider referral to a dietitian. |

Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[14] | |||

Current guidelines advise against the use of warfarin, sildenafil, co-trimoxazole, imatinib, N-acetylcysteine monotherapy or in combination with azathioprine and prednisolone, ambrisentan, bosentan and macitentan in patients with IPF who do not have a known alternative indication for its use[2]

.

Supportive care from healthcare professionals

The rate of disease progression and associated symptoms in IPF is variable. Antifibrotics can modify the course of disease, and slow the decline in lung function and exercise capacity, but are unlikely to improve symptoms, such as breathlessness, cough and fatigue. NICE has made recommendations about supportive care for patients with IPF (see Box)[4]

.

Box: The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommendations on supportive care for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Provision of information

- Provide patients with information and support on investigations, diagnosis and management from an interstitial lung disease specialist physician or nurse (or pharmacist). It is recommended that prognosis is discussed with people with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in a sensitive manner and information on severity of disease and average life expectancy is included;

- Life expectancy is highly variable and dependent on rate of disease progression and should be handled sensitively and based on ongoing assessment.

- Smoking cessation advice and referral

- Stopping smoking can slow the progressive loss of lung function and reduce symptoms, such as cough and sputum production, as well as the need for medicine. Patients with IPF who smoke should be actively encouraged to stop smoking and referred to smoking cessation services.

- Pulmonary rehabilitation

- Recommend annual influenza and five-yearly pneumococcal vaccinations;

- Refer for pumonary rehabilitation (PR), which can improve exercise tolerance and health-related quality of life. PR programmes vary in content and duration, and are often aimed at patients with COPD rather than IPF. Targeted PR for patients with IPF, including exercise training, nutritional counselling and education, is desirable.

- Palliative care

- This should be offered to people with IPF from the point of diagnosis.

- Disease-modifying pharmacological interventions

- Consider use of disease-modifying pharmacological interventions and manage any comorbidities according to best practice.

- Lung transplantation

- Discuss lung transplantation as a treatment option for people with IPF who do not have absolute contraindications (i.e. age, body mass index and comorbidities are taken into account to assess suitability and likelihood of a successful transplant)[22]

.

- Discuss lung transplantation as a treatment option for people with IPF who do not have absolute contraindications (i.e. age, body mass index and comorbidities are taken into account to assess suitability and likelihood of a successful transplant)[22]

- Ventilation

- Oxygen administration reduces exertional breathlessness and improves exercise tolerance. Long-term home oxygen should be considered when oxygen saturations are less than 88% at rest, measured via an oximeter. Often, a six-minute walk test can support the decision for oxygen prescribing. Do not routinely offer mechanical ventilation (including non-invasive mechanical ventilation) to people with IPF who develop life-threatening respiratory failure.

- Review and follow-up

- Identify exacerbations and previous respiratory hospital admissions;

- Refer for assessment for lung transplantation;

- Consider psychosocial needs and referral to relevant services as appropriate;

- Refer to palliative care services;

- Assess for comorbidities every three months.

Source: Lederer DJ & Martinez F. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2018;378(19):1811–1823; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [CG163]. 2013. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg163 (accessed April 2019)

Antifibrotics are high-cost, high-risk specialist medicines that require in-depth prescriber knowledge. If prescribed incorrectly, the patient could experience avoidable adverse effects that could lead to serious harm or fatality. For this reason, prescribing of antifibrotics is limited to specialist ILD settings and, at present, cannot be shared with primary or secondary care providers.

Role of the pharmacist

Pharmacists working in a specialist setting with routine contact with IPF patients are likely to be involved in supporting patients to make decisions on treatment, providing advice on preventing and managing potential adverse effects, and overseeing the prescribing and supply of antifibrotic therapy, where appropriate. In this setting, the pharmacist may also undertake a personalised medicine review to elicit a full medicine history, rationalise and optimise prescribed therapies, and deprescribe inappropriate or harmful therapies.

Comorbidities that contribute to breathlessness may alter patient perception on the effectiveness of antifibrotic therapy. Therefore, it is important that patients with co-existing asthma and/or COPD have effective therapy for those conditions to improve QOL and clinical outcomes. It is equally important that patients misdiagnosed with asthma and/or COPD have this diagnosis reviewed and related therapy deprescribed where there is no evidence of airway disease. Other comorbidities include lung cancer, GORD, pulmonary hypertension, sleep apnoea and coronary artery disease[1]

; these conditions should be managed by specialists and/or GPs in primary care.

When selecting antifibrotic therapy, all cautions and contraindications should be carefully considered, including hypersensitivity, hepatic impairment, renal impairment and cardiovascular history. Pirfenidone is primarily metabolised by Cytochrome P enzymes in the liver (including CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP2E1) and, therefore, interacts with inhibitors and inducers, such as omeprazole, smoking, grapefruit juice and rifampicin.

Nintedanib is a substrate of P-glycoprotein (efflux pump). Co-administration with P-glycoprotein inhibitors or inducers can increase or decrease exposure to nintedanib, respectively. Patients can be educated by specialist pharmacists on avoiding interactions where possible and recommendations made to the GP for potential alternative medicines.

It has been suggested that around a third of patients feel inadequately informed, making specialist pharmacists well-placed to counsel patients on their diagnosis, offer them a choice of therapy where appropriate, and educate them on disease course, treatment strategies and prognosis from onset of disease. At ongoing review, pharmacists can help to assess tolerability and adherence to therapy, and alleviate any concerns patients may have about their condition and/or medicines.

Although pharmacists in primary and secondary care settings may not be directly involved in the initiation, monitoring and supply of antifibrotics, they may have a role in the identification and management of patients with IPF in certain situations. This includes referring patients for further investigations if they present with progressive breathlessness, a dry persistent cough and/or finger clubbing. Non-specialist pharmacists may be asked for advice and support on concomitant therapy, to check for drug interactions with newly prescribed medications or potential adverse effects. They should offer the advice and support that is appropriate or refer the patient to their specialist team, when necessary. In addition, patients diagnosed with IPF can be signposted to the British Lung Foundation website for further information (see useful resources box), local IPF support groups, smoking cessation clinics, vaccination clinics and pulmonary rehabilitation, where appropriate.

Summary

As patient numbers increase and the complex management of IPF is considered, pharmacists will need to work within multidisciplinary teams in their organisation and across the interface to offer integrated care. Sharing care may provide the best outcomes for patients and increase their access to medicines. Appropriate identification and management of acute exacerbations may prevent hospitalisation, adverse outcomes for patients and untimely death. Pharmacists have a role in helping patients understand more about IPF, the management of symptoms and disease progression. This is an area of interest and more resources are being utilised in research and development; therefore, it is expected that the identification, diagnosis and management of IPF will evolve.

Useful resources

- British Lung Foundation: https://www.blf.org.uk/

- Pulmonary Fibrosis Trust: www.pulmonaryfibrosistrust.org

- Pulmonary Fibrosis Wales: www.pulmonaryfibrosiswales.co.uk

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

- This article was amended on 2 March 2020 to change “Pirfenidone is cautioned for use in mild-to-moderate renal impairment (i.e. patients graded as Child-Pugh A and B)…” to “Pirfenidone is cautioned for use in mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment (i.e. patients graded as Child-Pugh A and B)”.

References

[1] Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline: treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An update of the 2011 clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192(2):e3–e19. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1063ST

[2] Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198(5):e44–e68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST

[3] Lederer DJ & Martinez F. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2018;378(19):1811–1823. doi: 10.1056%2FNEJMra1705751

[4] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [CG163]. 2013. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg163 (accessed April 2019)

[5] Chambers RC. Procoagulant signalling mechanisms in lung inflammation and fibrosis: novel opportunities for pharmacological intervention?Br J Pharmacol 2008;153(Suppl 1):S367–378. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707603

[6] Sgalla G, Lovene B, Calvello M et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: pathogenesis and management. Respir Res 2018;19(1):32. doi: 10.1186/S12931-018-0730-2

[7] NHS Choices. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. 2016. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/idiopathic-pulmonary-fibrosis/ (accessed April 2019)

[8] Collard HR, Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ et al. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an international working group report. 2016. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194(3):265–275. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0801CI

[9] Kreuter M, Polke M, Walsh S et al. A global perspective on acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (AE-IPF): results from an international survey. Eur Respir J 2018;52:OA542. doi: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2018.OA542

[10] Kim DS. Acute exacerbations in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res 2013;14(1):86. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-86

[11] Lynch DA, Sverzellati N, Travis WD et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a Fleischner Society white paper. Lancet Respir Med 2018;6(2):138–153. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30433-2

[12] Levy ML, Quanjer PH, Booker R et al. Diagnostic spirometry in primary care: proposed standards for general practice compliant with American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society recommendations: a general practice airways group document, in association with the Association for Respiratory Technology & Physiology and Education for Health. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18(3):130–147. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2009.00054

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pirfenidone for treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Technology appraisal guidance [TA504]. 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta504 (accessed April 2019)

[14] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Nintedanib for treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Technology appraisal guidance [TA379]. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta379 (accessed April 2019)

[15] Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet 377(9779):1760–1769. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60405-4

[16] King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 370(22):2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582

[17] Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370(22):2071–2082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402584

[18] EMC. Espriet 267mg hard capsules. 2018. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3705/smpc (accessed April 2019)

[19] EMC. Ofev 150mg soft capsules. 2018. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1786/smpc (accessed April 2019)

[20] Hughes G, Toellner H, Morris H et al. Real world experiences: pirfenidone and nintedanib are effective and well-tolerated treatments for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Med 2016;5(9):78. doi: 10.3390/jcm5090078

[21] Duck A, Pigram L, Errhalt P et al. IPF Care: a support program for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treated with pirfenidone in Europe. Adv Ther 2015;32(2):87–107. doi: 10.1007/s12325-015-0183-7

[22] Organ donation and transplantation. Policies and guidance. Donor lung distribution and allocation. 2018. Available at: https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/11831/pol230-lung-allocation.pdf (accessed April 2019)

You might also be interested in…

No clear evidence that cannabis-based medicines are successful treatment for chronic pain

Almost 90% of pharmacies report abuse from ineligible COVID-19 vaccination patients, survey reveals