Art Directors & TRIP / Alamy Stock Photo

Research shows that one in ten people are affected by depression at some point in their lives[1],[2]

. Characterised by feelings of low mood over a sustained period of time, depression is a leading cause of morbidity and has a major impact on mortality[3],[4]

. It is widely understood that patients with long-term health conditions are up to three-times more likely to experience depression than the general population, and it is reported that GPs spend approximately 30% of their time with patients who have a mental health condition[4]

.

For mild or subthreshold depression, treatment with antidepressants is not recommended because mild depression is characterised by symptoms that do not affect daily functioning while subthreshold depression is characterised as having fewer than five symptoms of depression. As a result, other strategies should be tried in the first instance[5]

.

Moderate depression is characterised by functional impairment and severe depression by a major effect on daily functioning[5]

. Therefore, treatment with antidepressants alongside psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy, are recommended[5]

. Evidence shows that only 30–50% of people with any type of depression respond to pharmacological or psychological interventions alone[6]

. Therefore, it is important to consider non-pharmaceutical interventions to help patients with depression.

There are many non-pharmaceutical interventions that could have a positive impact on a patient’s mood, such as sleeping well and following a healthy lifestyle. These interventions, which can be particularly helpful for patients with mild or subthreshold depression, can prevent the escalation of the condition and, therefore, the need for medicine.

It should be noted that there are several herbal products available on the market for depression, including St John’s wort. Although there is some evidence that there could be benefits from these products, they should not be prescribed or recommended to treat depression owing to the lack of robust trials, variation between preparations and potential drug interactions[5]

.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline recommends that, for all known or suspected cases of depression, patients should be offered support, education, careful monitoring and referral, as appropriate[5]

. Acknowledging the signs and symptoms of depression, as well as providing advice and support, is important for the patient. During a medicines review or a consultation, it is important to consider patients with a history of depression and those with risk factors, such as long-term conditions or social isolation. These patients should be asked the following questions during a consultation to help assess their mood:

- In the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

- In the past month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?[5],[7]

If the answer to either question is ‘yes’, then depression should be suspected and the patient should be referred to their GP for a full assessment.

It is difficult to discuss the risk of self-harm and suicide; however, it is important to raise this topic if depression is suspected or the patient appears to be at risk, in order to help evaluate the risks and signpost the patient to the correct place for help[5],[7]

. There is no evidence to suggest that asking can make the situation worse for the patient. There are many websites and charities available online for more information (see ‘Useful resources’).

As pharmacists frequently encounter patients with depression, they can guide patients in receiving the correct support to improve their mental health, as well as discussing pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical treatments. This article will focus on the non-pharmacological advice and support that can be offered to patients with depression.

Sleep hygiene

It is recommended that adults should get around seven to nine hours of sleep per night, allowing the body and mind to sufficiently recover and regenerate[8]

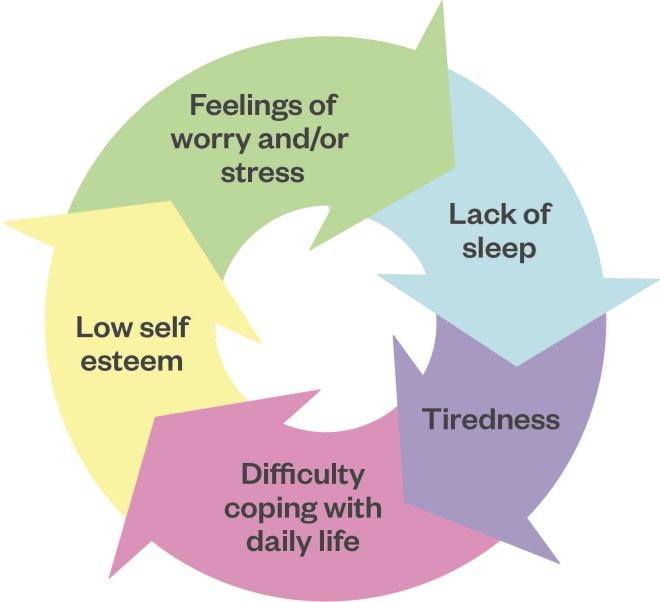

. There is an established connection between poor sleep and depression (see Figure); around 75% of patients with depression have symptoms of insomnia[9]

. Conversely, evidence shows that patients with insomnia are at high risk of developing depression and that residual insomnia can result in relapse of their condition[7],[10]

. In addition, insomnia can be distressing and affect quality of life, leading to anxiety and the risk of suicide; therefore, sleep hygiene is important for maintaining good mental health and improving quality of life for patients with depression[9]

.

Figure: The relationship between poor sleep and poor mental health

Source: Adapted from www.mind.org.uk

Improving sleep hygiene is the first-line treatment for patients with sleep problems (see Box 1). If a patient presents to the pharmacy with sleep problems, it is useful to carry out a review of the symptoms as it could be an early warning sign of depression. If undiagnosed depression is suspected, it is important to refer the patient to their GP for an assessment[7],[11]

. If other causes of insomnia are ruled out, then pharmacists should offer basic sleep hygiene advice and direct patients towards useful websites or applications, such as the Mental Health Foundation, NHS Choices and sleep apps available from the NHS Apps Library, such as Sleepio and Pzizz[12],[13],[14]

. Good sleep education is also beneficial for many physical health conditions and weight loss[8],[15]

.

Evidence to support sleep hygiene alone in improving sleep is lacking; however, the intervention is widely supported in guidelines and used in practice[5],[10]

.

Box 1: Sleep hygiene advice

To achieve a better quality of sleep, pharmacists should recommend that patients:

- Set specific times for going to bed and waking up, which helps establish a routine;

- Avoid napping during the day;

- Relax prior to bed (e.g. by taking a bath, reading a book and avoiding screens);

- Avoid caffeine, nicotine and alcohol six hours before going to bed (eliminate completely if possible);

- Avoid exercise within four hours of going to bed;

- Avoid eating a heavy meal just before going to bed;

- Create a peaceful environment (e.g. minimise light and noise, ensure the room temperature is comfortable i.e. not too hot or cold, between 18–24â—¦ C is ideal);

- Use the bedroom just for sleep (i.e. do not watch TV or complete work in bed).

Sources: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[5]

; NHS[8]

; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[10]

Alcohol, drugs and nicotine

Reducing smoking, alcohol consumption and the use of illicit drugs has a positive effect on physical health, which is normally worse in patients with mental health problems. One in three people who regularly use illicit drugs and/or alcohol are thought to experience depression, because both affect neurotransmitters which affect mental health[16],[17]

. It is not clear whether regular users of drugs or alcohol are more susceptible than non-users to feeling depressed, or if people with low mood or anxiety often use alcohol and/or drugs as self-medication to help them deal with difficult situations or to help relieve stress[17]

.

It is important for healthcare professionals to feel comfortable discussing substance misuse with all patients, but this is particularly important in patients with depression. Substance misuse can affect daily living and, in turn, make life more difficult, which can predispose people to developing depression[15]

. These conversations can be difficult, but being open makes it easier to provide advice and manage the patient who could be at risk.

For example, a quick question could be asked to determine whether further screening is required (e.g. in the past year, have you used alcohol, smoked cigarettes, used prescription drugs that are not prescribed for you, or used any illegal drugs?). If it is suspected that the patient is at risk, it is important to explain the health risks to them and ask them if they are ready to stop using these substances.

It can be helpful to use a tool, such as Audit C, to identify hazardous drinkers or those with a potential problem[18]

. Reducing alcohol and illegal drug use can be helpful, but the patient should be referred to a specialist for help if a more serious problem is suspected.

Patients with depression are twice as likely to smoke cigarettes compared to the general population[17]

. Although smoking is habitual, people often smoke to cope with stress, with some saying that it helps them to relax. However, research has shown that nicotine can contribute to stress[15]

. The relaxation experienced from nicotine is short-lived and is replaced by anxious feelings of withdrawal and cravings. Patients with depression may require more support when they are attempting to stop smoking as it has been reported that withdrawal symptoms are worse in this population[12],[15]

.

Pharmacists should discuss smoking cessation with patients and offer nicotine replacement where appropriate. It is also useful to talk about other ways to cope with stress if the patient wishes to quit smoking.

Healthy diet

There is limited evidence on the effects of different diets in reducing symptoms of depression. However, there is evidence that following a healthy diet and weight loss can contribute to an increase in self-esteem and a more positive outlook[15]

.

Although the association is not fully understood, it is thought that diet may affect several biological factors which could contribute to the development of depression[19]

. Therefore, making dietary changes could have a positive effect on the patient’s mood. The British Dietetic Association recommends maintaining a healthy diet to keep physical and mental health stable[20]

.

Some people may have a poor understanding of a healthy diet and need advice (see Box 2)[17],[20],[21]

. However, if there are concerns that someone is obese or underweight, then they may require referral to their GP and/or a dietician for further advice and a structured diet plan.

Box 2: Dietary advice to aid the prevention of depression

The British Dietetic Association recommends the following to help with low mood:

- Eat regular small meals to provide the brain with a regular supply of glucose and help regulate mood;

- Ensure a balance of ‘good fats’ from sources such as nuts and seeds, which will help maintain brain structure and functioning;

- Eat more wholegrain foods, fruits and vegetables, which provide a steady supply of glucose to the brain and contain B vitamins and zinc, which have been proven to help prevent depression;

- Eat protein with every meal. Foods such as eggs, fish, lentils and beans are good sources of protein that contain tryptophan, which can help with symptoms of depression;

- Eat oily fish containing omega-3. Omega 3 helps promote good brain health and although more evidence is needed into its effects in depression, it is thought that it can help people with depression;

- Ensure adequate fluid intake as dehydration can contribute to low mood;

- Avoid excess alcohol, which can deplete the body of B vitamins and, in turn, contribute to low mood and depression. It can also affect the brain, making it more likely for a person to experience depression. Excess alcohol can impact social relationships, increasing the risk.

Sources: Royal College of Psychiatrists[17]

; Association of UK Dietitians[20]

; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

[21]

Exercise

It is recommended that people should undertake at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week to stay healthy[22]

. NHS guidelines state that exercise can have a positive impact on a person’s mood and can help with the management of depression[22]

. Daily exercise can decrease stress; increase serotonin levels; help with weight loss; help establish a normal routine; and can help improve sleep, all of which can aid the symptoms of depression[17],[22]

. Taking part in group physical activities can reduce social isolation and loneliness, which is particularly relevant for older people[23],[24]

.

A 2013 Cochrane review concluded that there was no evidence that exercise alone was more effective in depression than psychological therapies, although there was a moderate increase in mood when compared with the control group[25]

. This review also showed that there is some benefit from exercise, and it can be trialled as an intervention in milder forms of depression and used as an adjuvant for short-term intervention prior to more traditional treatments, such as antidepressants or psychological interventions. A more recent review, published in 2018, looked at the impact of aerobic exercise on depression.It demonstrated that aerobic exercise improves symptoms of depression in patients who were enrolled in supervised exercise sessions[26]

.

Regular exercise also helps to reduce the risk of major illness, such as diabetes and stroke, by 50% and reduces the risk of premature death by 30%[27]

. Patients with long-term health conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension, are twice as likely to experience depression; however, by exercising and improving diet, physical health conditions can be managed and the likelihood of developing depression may reduce[15]

.

Patients with depression may lack motivation; therefore, it is important that they find a form of exercise they enjoy as this will encourage them to continue with it. If patients have not done exercise for a while, are unfit or have long-term health conditions, they may be able to get exercise ‘on prescription’ from their GP — depending on their circumstances and what is available in their local area; they may be entitled to free or reduced-cost sessions at certain gyms[28]

. There is the option of social prescribing, where patients can be referred to a community link worker who can work with the patient to achieve their goals and facilitate them to attend community exercise groups and sessions. This could be part of health coaching, which differs from social prescribing in that emphasis tends to be placed on the behaviour change, rather than connecting people with community groups and services[29]

.

Discuss the benefits of exercise with patients with depression, and direct them towards websites and activities that may be helpful. A discussion can be started by asking the patient how much exercise they do per week and explaining how it may be beneficial to increase this (e.g. improve mood and reduce stress to aid better sleep). During this discussion, it would be helpful to explore what type of exercise they may enjoy and direct them to how they may participate in this. For example, if they are interested in running, they could be encouraged to use the NHS ‘Couch to 5K’ app, a running course for beginners, or simply be given details of their local swimming pool or gym.

Mindfulness and meditation

A form of meditation originating from Buddhism, mindfulness is defined as the act of being present in the moment, giving yourself your full attention and clearing your mind from stresses of everyday life. Its benefits include reducing stress and subsequently managing mental health. Examples of activities include yoga and tai chi, which combine mindfulness and exercise and are widely available in the community, both as part of gym class programmes and privately-run classes.

NICE recommends mindfulness as a non-pharmacological treatment option for recurrent depression and there is evidence that ‘mindfulness CBT’, which involves using mindful techniques alongside CBT to enable the patient to plan how to better deal with difficult situations, is equivalent to antidepressants in improving mood and preventing relapse of depression[5],[30]

. There is also growing evidence for the use of mindfulness-based stress reduction

[5],[31]

. Practising mindfulness has been shown to help improve sleep, and there is evidence that, compared to control patients, those who practice mindfulness have reduced stress and anxiety[32]

.

Waiting lists for mindfulness CBT can be lengthy and a referral is often required. However, there are lots of useful online sites and applications, such as the Oxford Mindfulness Centre and apps such as Chill Panda and Be Mindful, which are available through the NHS Apps Library, to which pharmacists can direct patients. Patients in England registered with a GP can self refer for psychological therapies via the NHS website ‘Improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT)’ service[33]

. The service can provide digitally enhanced therapy delivered online or via mobile phone, allowing patients to learn by self-study with support from trained therapists[34]

.

Conclusion

Pharmacists must be mindful of how to approach and advise patients with depression. In community pharmacy, a medicines use review or advice through the new medication service could be the perfect opportunity to discuss interventions that may be helpful for the patient. Patients can be directed towards online advice around diet and exercise, and there are lots of resources that provide support for meditation and mindfulness. For patients that require further support, they can be directed to their local IAPT service[34]

. If there is a concern about someone’s mood or there is a risk of self-harm, patients should be referred to their GP or local hospital emergency department.

The interventions described in this article could help improve the patient’s mental state, wellbeing, physical health and could help prevent prescriptions for antidepressants.

Useful resources

- Mental Health Foundation. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk

- Mind. Available at: http://www.mind.org.uk

- Rethink Mental Illness. Available at: http://www.rethink.org

- Samaratans. Available at: http://www.samaritans.org

- Sane. Available at: http://www.sane.org.uk

- Alcoholics Anonymous. Available at: http://www.alcoholics-anonymous.org.uk

References

[1] GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1545–602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6

[2] Public Health England. Common Mental Health Disorders. 2019. Available at: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/common-mental-disorders/data#page/1/gid/1938132720/pat/46/par/E39000018/ati/154/are/E38000020 (accessed February 2020)

[3] Harris E & Barraclough B. Excess mortality of mental disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1998;173 (1):11–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.1.11

[4] McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R & Brugha T. Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014. 2016. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/556596/apms-2014-full-rpt.pdf (accessed February 2020)

[5] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: recognition and management. Clinical guideline [CG90]. 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG90 (accessed February 2020)

[6] Nutt D, Blier P, Cleare A et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of 2008 British Association for psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol 2015;29(5):459–525. doi: 10.1177/0269881115581093

[7] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical knowledge summaries: depression. 2019. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/depression (accessed February 2020)

[8] NHS. 10 tips to beat insomnia. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/sleep-and-tiredness/10-tips-to-beat-insomnia (accessed February 2020)

[9] Nutt D, Wilson S & Patterson L. Sleep disorders are core symptoms of depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2008;10(3):329–236. PMID: 18979946

[10] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical knowledge summaries: insomnia. 2015. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/insomnia#!scenario (accessed February 2020)

[11] Montano CB. Recognition and treatment of depression in a primary care setting. J Clin Psychiatry 1994;55 Suppl:18–34. PMID: 7814355

[12] Mental Health Foundation. Mental Health Foundation. 2020. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk (accessed February 2020).

[13] NHS. How to get to sleep. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/sleep-and-tiredness/how-to-get-to-sleep (accessed February 2020)

[14] NHS. Sleep apps. 2019. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/apps-library/category/sleep (accessed February 2020)

[15] Mind. Depression. 2016. Available at: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/depression (accessed February 2020)

[16] Montano CB, Hirschfeld RMA, Nemeroff C & Dunner DL. Recognition and treatment of depression in a primary care setting. J Clin Psychiatry 1994;55(12 Suppl):18–34. PMID: 7814355

[17] Royal College of Psychiatrists. Problems and disorders. 2019. Available at: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/problems-disorders (accessed February 2020).

[18] Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J & Monteiro M. World Health Organization Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. 2001. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67205/WHO_MSD_MSB_01.6a.pdf;jsessionid=49CA0932C2323675786870D42D52E768?sequence=1 (accessed February 2020)

[19] Sanhueza C, Ryan L & Foxcroft DR. Diet and the risk of unipolar depression in adults: systematic review of cohort studies. J Hum Nutr Diet 2013;26(1):56–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01283.x

[20] The Association of UK Dietitians. Depression and Diet: Food Fact Sheet. 2018. Available at: https://www.bda.uk.com/foodfacts/depression_diet (accessed February 2020).

[21] Appleton KM, Sallis HM, Perry R et al. Omega-3 fatty acids for depression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015. Available at: https://www.cochrane.org/CD004692/DEPRESSN_omega-3-fatty-acids-depression-adults (accessed February 2020)

[22] NHS. Physical activity guidelines for adults aged 19 to 64. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise (accessed February 2020)

[23] Robins LM, Jansons P & Haines T. The Impact of Physical Activity Interventions on Social Isolation among Community - Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Research & Reviews: Journal of Nursing & Health Sciences 2016;2(1):62–71

[24] Shvedko A, Whittaker AC, Greig CA & Thompson JL. Physical activity interventions for treatment of social isolation, loneliness or low social support in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Psychol Sport Exerc 2018;34:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.10.003

[25] Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(9). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6

[26] Morres ID, Hatzigeorgiadis A, Stathi A et al. Aerobic exercise for adult patients with major depressive disorder in mental health services. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety 2019;36(1):39–53. doi: 10.1002/da.22842

[27] NHS. Living Well. Exercise. Benefits of exercise. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/exercise-health-benefits (accessed February 2020)

[28] NHS Inform. Exercise for depression. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhsinform.scot/healthy-living/mental-wellbeing/low-mood-and-depression/exercise-for-depression (accessed February 2020)

[29] NHS England. Social prescribing and community-based support. Summary guide. 2019. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/social-prescribing-community-based-support-summary-guide.pdf (accessed February 2020)

[30] Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT) a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:63–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62222-4

[31] Chen KW, Berger CC, Manheimer E et al. Meditative therapies for reducing anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Depress Anxiety 2012;29(7):545–562. doi: 10.1002/da.21964

[32] NHS. Mindfulness. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stress-anxiety-depression/mindfulness (accessed February 2020)

[33] NHS England. Adult Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme. 2019. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/adults/iapt (accessed February 2020)

[34] NHS. Find a psychological therapies service (England only). 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/service-search/find-a-psychological-therapies-service (accessed February 2020)

You might also be interested in…

Specialist mental health pharmacist clinics in primary care: a service evaluation supporting integrated neighbourhood working

Stopping antidepressants in pregnancy linked to higher risk of mental health emergencies