Science Photo Library

In this article you will learn:

- The initial action you should take when a patient experiences an epileptic seizure

- Advice you should give patients with epilepsy to reduce seizure risk

- How status epilepticus is managed

Jane Edwards, 49, is taken ill in the prescription waiting area of the pharmacy. Her husband informs you that she is having a seizure. The patient is conscious and making a low grunting noise. Her head turns to the left and she begins to rock forward and back in the chair, moving her arms and legs rhythmically.

Her husband says: “I suspect it’s going to be one of her big seizures, can you help me get her on this floor before she goes unconscious and starts to convulse?”.

Jane is taking the following medicines:

- Tegretol prolonged release two 400mg tablets BD;

- Lamotrigine one 100mg tablet BD;

- Buccolam oromucosal suspension 10mg/2ml PRN.

Step one: managing a seizure

Seizures are classified into two main types: focal (previously called partial) and generalised (sometimes referred to as primary generalised). In simple focal seizures, the person is conscious, aware of what is going on and will recall events after the seizure. In complex focal seizures, the person is conscious but loses awareness and will not recall the event.

Focal seizures present differently depending on the area of the brain affected. A focal seizure in the temporal lobes may involve the person smelling a strong smell or experiencing a sensation of déjà vu; whereas a focal seizure in the frontal lobes may result in head turning or jerky movements of the head or arms.

Generalised seizures include tonic-clonic seizures, myoclonic jerks and absence seizures. In these seizures, the whole brain is involved from the start and consciousness is lost (albeit briefly in the case of myoclonic jerks and absence seizures). It is not uncommon for a focal seizure to evolve into a tonic-clonic seizure (also known as secondary generalised epilepsy).

What is epilepsy?

Epilepsy, the tendency to have recurrent seizures, is a commonly occurring neurological condition that affects around 50 million people worldwide, of whom 80% are in developing countries[1]

.

Premature mortality in people with epilepsy is two to three times greater than that of the general population[2]

. Each year in the UK around 800 people die from epilepsy, with around 600 experiencing sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP)[2]

. People with epilepsy have a higher incidence of depression, suicide and accidents, as well as long-term conditions including cardiovascular and respiratory disease[3]

. People with epilepsy can experience significant memory problems, even at a young age, and report having few friends, relationship issues and employment difficulties (often associated with being unable to drive).

The nature of a person’s epilepsy is dictated by the area of the brain affected, the pattern of the spread of the electrical discharge that occurs during the seizure, and the underlying cause. Possible causes include: brain damage during birth; head injury; infection (e.g. meningitis); vascular disease; and brain tumour. In many cases, the precise cause is not discovered. Epilepsy can start at any age, but most commonly first appears in childhood or in later life.

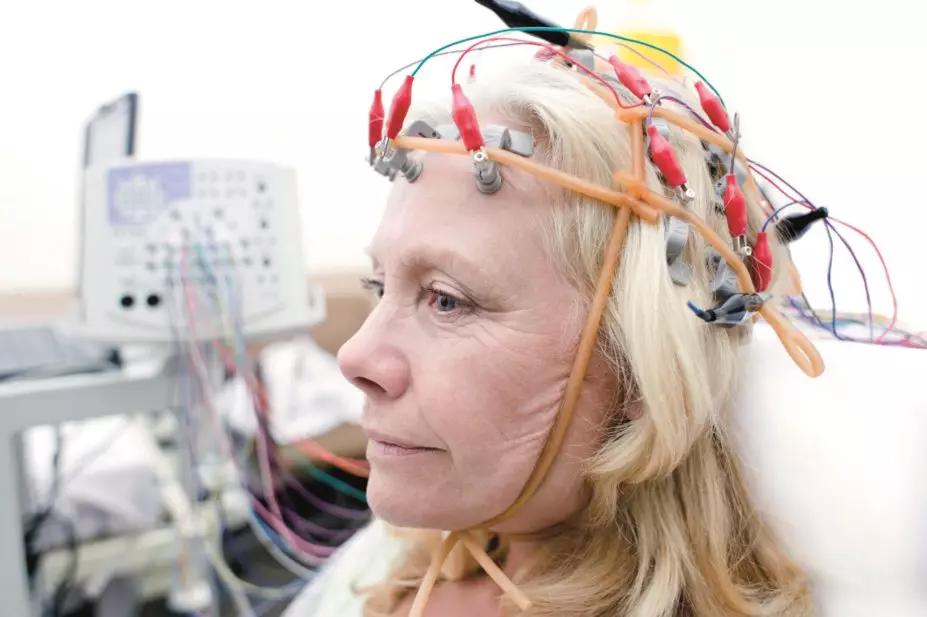

Epilepsy is diagnosed mainly on the basis of clinical history, as electroencephalograph (EEG) often fails to detect seizure activity.

The first priority when someone is having a seizure is to protect them from harm. Someone having a simple focal seizure (see ‘What is epilepsy?’) will be able to respond to instructions. They may be able to move to a quiet, private area, such as the consultation room. Ideally, they should be assisted to sit on the floor (so they do not fall off a chair). A person having a complex focal seizure may not be able to respond and may have to be left in situ.

Patients having a seizure can be guided but should never be forced or restrained, and should be supervised at all times; someone having a generalised tonic-clonic seizure could be badly injured or even die because of danger in their surroundings. You should move any items that could cause the person harm, such as chairs or free-standing shelving. It is best to avoid moving the patient unless they are in considerable danger.

Jane appears to be experiencing a focal seizure that is evolving to a generalised tonic-clonic seizure. This gives her husband and the pharmacist time to lower her carefully to the floor. If possible, something soft should be used to provide a cushion for her head.

A person with epilepsy should not have anything put into their mouth at any stage, and food or drink should not be given until they have recovered fully.

Once Jane is in a safe position, the pharmacy team should assist in maintaining her privacy and dignity. The team can help by cordoning off the area, or laying a blanket or coat over the person in case there is loss of bladder control, which may occasionally occur during a seizure.

Around 80% of seizures will stop in under two minutes[4]

. However, in some cases seizure activity is prolonged. Once any danger to the patient has been removed, the seizure should be timed. If the seizure lasts two minutes longer than usual, then status epilepticus should be suspected (see ‘Status epilepticus’). Jane’s patient medical record suggests she has experienced status previously, as she has been prescribed rescue medication (Buccolam). Her husband will have been trained to administer a single dose.

If it is unknown how long the person’s seizures usually last, an ambulance should be called if it continues for longer than five minutes or if the person has repeated seizures.

An ambulance should also be called if it is known (or suspected) to be the person’s first seizure, or if they injure themselves during the seizure.

Status epilepticus

Status epilepticus (status) is a medical emergency defined as a seizure lasting for more than 30 minutes. A prolonged convulsive seizure can result in dramatic physiological changes that can rapidly lead to significant neuronal damage. Status is fatal in around 10–20% of cases.

Status requires immediate medical treatment once it is obvious the seizure is not stopping in the usual time; patients should not be left having a seizure for 30 minutes before a diagnosis of status made[4]

. Status should be suspected if the seizure lasts for two minutes longer than usual for the patient.

The treatment of choice for status is intravenous lorazepam (4mg by slow intravenous infusion into a large vein in patients over 12 years; for children 100mcg/kg to a maximum of 4mg), repeated once after ten minutes if the patient fails to respond. Alternative treatments include buccal midazolam (although this use is unlicensed) or diazepam given by rectal solution.

There are two main products containing midazolam for buccal use in the UK: Buccolam and Epistatus. However, neither product is licensed for use in adults (Buccolam is only licensed for children aged up to 18 years). The two products contain different salts of midazolam and are available in different strengths. There have been prescribing and dispensing errors associated with these products and pharmacists should ensure the appropriate product is given.

Step two: immediately after the seizure

Patients should be allowed to recover following an epileptic seizure; they should not be ‘brought round’ by any method. If the patient is unconscious, they can be put in the recovery position once the seizure is over. If they are conscious, it may help to speak calmly and tell them where they are and what has happened; seizures can be frightening for patients, even if they have had epilepsy for many years.

Patients who have recovered from a seizure can go home, although someone should stay with them. A person who has just had a seizure must not be allowed to drive; the UK Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) requires that a patient who has had a seizure must surrender their driving licence until they are seizure-free for at least one year.

When someone has a seizure:

1. Ensure you are not in danger;

2. If the person responds to instructions, move them to a quiet, private area and (preferably) sit them on the floor. If they do not respond to instructions, do not attempt to move them;

3. Protect the person from harm. Look to remove nearby hazards that could hurt them. Guide the person, but never attempt to force or restrain them;

4. Supervise the person at all times. If possible, try to cushion their head;

5. Never put anything in the mouth of someone having a seizure;

6. Try to ensure the person’s dignity is maintained (they may lose bladder control);

7. Call an ambulance if the person has repeated seizures, if they injure themselves during a seizure, or if this is their first seizure;

8. If the person is known to have epilepsy, start timing the seizure. If the seizure lasts two minutes longer than normal (or five minutes if you do not know how long the seizure usually lasts), call an ambulance;

9. Once the seizure is over, do not attempt to ‘bring round’ the person by any method. If they are unconscious, place them in the recovery position;

10. Once the person is conscious, speak calmly and tell them what happened. The person should not be given food or drink until they have recovered fully.

Step three: managing medicines

Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) are the mainstay of treatment for most patients with epilepsy. There are many triggers for seizures (see ‘Possible seizure triggers’) but low levels of AEDs are a common cause. Adherence rates for AEDs are around 30–50%[5]

,[6]

, and non-adherence is associated with a 20% increased risk of seizures and a three-fold increase in mortality rates[6],[7]

.

It is important to remember that people with epilepsy can experience memory problems and should be supported with anything that can help with remembering their medicine (e.g. dosette boxes, reminder alarms).

Possible seizure triggers

- Sleep deprivation

- Reduced or inadequate antiepileptic medication

- Low blood glucose (less often, high)

- Stimulant/other pro-convulsant intoxication

- Sedative or ethanol withdrawal

- Hormonal variations

- Stress

- Fever or systemic infection

- Concussion and/or closed head injury

Consistency of supply is a big issue for people with epilepsy. In November 2013, the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency issued guidance on when epilepsy medicines should be prescribed by brand due to issues with variability between products from different manufacturers[8]

.

Receiving different forms of their usual AEDs can be confusing or anxiety-inducing for patients. This may affect seizure control and result in non-adherence.

The expiry dates of buccal midazolam products are not long (Epistatus multi-dose bottle has a shelf-life of two years, while the pre-filled syringes have a shelf-life of one year; Buccolam syringes have an 18-month shelf-life). Health professionals should record the expiry dates for these products and remind patients and carers when they are likely to be running out.

Trudy Thomas PhD MRPharmS is director of taught graduate studies at the Medway School of Pharmacy and a locum pharmacist who specialises in epilepsy. She would welcome contact (t.thomas@gre.ac.uk) from other pharmacists who have an interest in epilepsy or other healthcare professionals who are interested in working more closely with pharmacists.

References

[1] World Health Organization. Epilepsy fact sheet (No. 999). Geneva: WHO 2012.

[2] Hanna NJ, Black M, Sander JWS et al. The National Sentinel Clinical Audit of Epilepsy-Related death. Epilepsy, Death in the Shadows. London: The Stationery Office 2002.

[3] Buck D, Jacoby A, Baker GA et al. Patients’ experience of injury as a result of epilepsy. Epilepsia 1997;38:439–444.

[4] Rosenow F & Krake S. Status Epilepticus. Handbook of Clin Neurol 2012;108(47):813–819.

[5] Faught E. Adherence to antiepilepsy drug therapy. Epilepsy and Behavior 2012;25:297–302.

[6] Manjunath R, Davis KL, Candrilli SD et al, Association of antiepileptic drug nonadherence with risk of seizures in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy and Behavior 2009;14:372–378.

[7] Faught E, Duh MS, Weiner JR et al. Non-adherence to antiepileptic drugs and increased mortality: findings from the RANSOM study. Neurology 2008;71:1572–1578.

[8] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Drug safety update. Antiepileptic drugs. London: MHRA 2013.