Sheila Terry / Science Photo Library

Pharmacy is a frequent point of contact for patients with a range of eye conditions. Dry eye is a particularly common condition, with a reported prevalence of between 1 in 20 people and 1 in 3 people[1]

. Patients, typically with mild-to-moderate levels of dry eye, will often present to their optometrist or community pharmacist for advice, management and treatment.

A 2016 survey of members of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, conducted by The Pharmaceutical Journal, revealed that 57% of community pharmacists (n=227) said that they saw a patient with an eye condition at least once a day; a third said that they saw a patient with a dry eye condition at least once a day; and 80% reported that they saw a patient with a dry eye condition at least once a week[2]

.

Many patients can be effectively managed through pharmacy without the need for referral to their GP or ophthalmologist. This article aims to provide an overview of the changes to the definitions, diagnosis and treatment of dry eye included in the 2017 report of the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS)[3]

, as well as what these changes mean for pharmacists and pharmacy teams.

Production of the TFOS DEWS report

The initial focus on dry eye disease largely began with the report of the National Eye Institute/Industry Workshop on Clinical Trials in Dry Eyes[4]

. This was the first formalised attempt to define and classify dry eye disease, in addition to reviewing its management, treatment, and the design of clinical trials.

In 2007, this was followed by the TFOS publication of the DEWS report, produced by 58 members from 11 countries[5]

. Produced as a special issue of the journal Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science, the free report has become the ‘go to’ source of information for clinicians, researchers and industry alike.

In recognition of the exponential publication of literature since the first DEWS report, 2017 sees the publication of an updated report — TFOS DEWS II— and provides a consensus view on what dry eye is, what causes it, how it should be diagnosed and how it is best managed[3]

. Table 1 summarises the key changes in clinical guidance included in the updated TFOS DEWS II report.

| Table 1: Overview of clinical guidelines that have chnaged between the 2007 and 2017 Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) reports[3] ,[5] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| TFOS DEWS 2007 guideline | TFOS DEWS II 2017 guideline | Reason for change | |

| Definition | Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the tears and ocular surface that results in symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance, and tear film instability with potential damage to the ocular surface. It is accompanied by increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface. | Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterised by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play aetiological roles. | Misperception that pathophysiological features were stated as essential diagnostic criteria in original. Desire to encapsulate definition within a single sentence. Symptom specificity reduced to encompass a wider range of patient reported experiences. |

| Diagnosis | Symptomology questionnaire; osmolarity; non-invasive tear break-up time; Tear function Index — quotient of the Schirmer test and fluorescin visualised tear clearance. | Symptomology with Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) or the Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5 item) + at least one positive result from: non-invasive tear break-up time; osmolarity; ocular surface staining. | New criteria better defined with clear cut-off values. Ocular surface damage (that includes the eylid margins) replaces the more poorly validated Tear Function Index. |

| Management | Severity matrix; treament recommendations by four severity levels. | Need to sub-classify as aqueous deficinet or evaporative emphasised. Severity matrix abandoned. Treatment recommendations by four severity levels (many more evidence-based treatments since 2007). | Sub-classification aids in targeting treatment to individual patients. Severity matrix could classify patients across several severity categories simultaneously. |

Anatomy of the tear film and its production

Before discussing dry eye in more detail and the implications of the TFOS DEWS II report, it is necessary to understand the anatomy of the tear film and more about its production[6]

.

Despite being only around one tenth of the thickness of a human hair, the tear film is vital for maintaining healthy and comfortable eyes, in order to provide clear vision. Tears bathe, nourish and protect the eye’s surface from dryness, allergy and infection, and work to eliminate the irritants that cause discomfort and keep the surface of the eye moist[7]

.

When the eye fails to produce sufficient tears, dry eye symptoms (dryness, burning, eye fatigue and even watering, along with transient visual disturbance [see later]) may occur and, if left untreated, can result in damage to the eye’s surface[7]

.

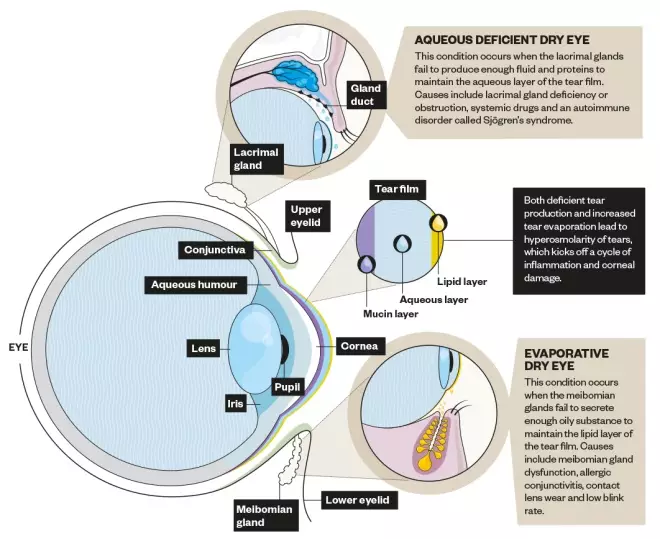

The three main components of the tears are produced by glands in the orbit and the eyelid, and by cells overlying the white of the eye, in a carefully ordered structure to protect the ocular surface (see Figure 1). The tear film is often described as consisting of three layers, but it is likely these are not discrete. The lipid layer is the oily top layer of the tear film, produced mainly by the meibomian glands that are contained within the lids with openings along the lid margins. This layer helps to prevent tear evaporation and to spread the tear film over the surface of the eye. The aqueous layer is the watery middle layer of the tear film, produced by the lacrimal gland situated in the upper lateral region of each orbit. Finally, the mucin (or mucous) layer, produced by the goblet cells located in the conjunctival tissue over the white of the eye (the sclera), coats the cornea (the clear window to our vision) and holds the tear film to its surface[6]

,[7]

.

Figure 1: Structure of the eye

Source: Alisdair MacDonald

Glands in the orbit and the eyelid produce the three main components of tears.

Tears flow across the ocular surface from the eyelid glands where they are produced, spread by each blink. They are drawn along the tear meniscus (the pool of tears along the upper and lower inner lid margins), and drain through small ‘canals’ (puncta) in the nasal aspect of the eyelid into the nose.

Dry eye disease

Epidemiology

Studies suggest that between 5% and 50% of the adult population have symptoms of dry eye disease, and the condition is more common in Asian populations and in females[1]

. It is associated with other medical conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes and thyroid disease, as well as with anxiety and depression. Dry eye can develop after surgical procedures such as LASIK (laser), cataract or cosmetic surgery[8]

.

Prolonged use of computers, video games, tablets and mobile phone screens can also bring on the condition. Other environmental factors that contribute to symptoms can include allergies, pollution, wind, cigarette smoke, dry environments, contact lens wear, not drinking enough water and a poor diet.

Prescription and over-the-counter medications including eye drops, allergy medication, anti-depressants and sleeping aids can also cause symptoms[9]

.

Definition and aetiology

The consensus definition of dry eye disease from the TFOS DEWS II report is: “Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterised by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play aetiological roles”[10]

.

The original TFOS DEWS workshop was the first to acknowledge that dry eye was a disease entity, with a multifactorial aetiology[11]

. Symptoms are critical to dry eye disease diagnosis and differentiate it from subclinical ocular surface disease, although such disease may also need management, particularly in situations known to induce dry eye such as refractive surgery or low humidity environments. Visual symptoms include discomfort (typically described as dryness, burning, eye fatigue and even watering) along with transient visual disturbance (which occurs when the critical optical refracting surface of the tear film for high quality vision is disrupted). The phrase ‘loss of homeostasis’ has been introduced to convey the imbalance that is induced in the state of equilibrium of the tear film by a variety of causes. This is considered to be the unifying characteristic that describes the fundamental process in the development of dry eye disease[7]

.

The core mechanism of dry eye is tear hyperosmolarity, which is now recognised as the key distinguishing feature of the disease. The increased solute concentration damages the ocular surface, both directly and indirectly, by initiating inflammation. Cells from the eye’s surface are damaged and lost in this process, causing tear film instability, such that the tears can no longer protect the ocular surface in the periods between blinks, and this leads to symptoms of dryness. This premature destabilisation, described as tear breakup, exacerbates and amplifies tear hyperosmolarity and completes the vicious circle of self-perpetuating events that lead to dry eye disease[7]

.

The two main sub-classifications of the disease are aqueous-deficient dry eye (ADDE) and evaporative dry eye (EDE), with patients on a spectrum between these two types. In ADDE, tear hyperosmolarity arises from reduced lacrimal secretion, as a result of excessive drainage or more commonly, from reduced lacrimal gland tear production (see Figure 1). In EDE, excessive evaporation from the exposed tear film surface is the cause of tear film hyperosmolarity (see Figure 1)[10]

. EDE has been reported to be four times more common than ADDE[12]

.

Diagnosis

There are a wide range of measures that have been proposed as diagnostics for dry eye disease. These include tests of tear stability (such as the time taken for the tear film to ‘break’ on the ocular surface), tear volume (such as that measured from the tear meniscus height or from the length of paper [Schirmer] or dyed string [Phenol Red Thread test] that wets when placed in the tear meniscus over a set period of time), ocular surface damage (such as ocular surface staining from fluorescein, lissamine green and rose bengal dyes), and patient symptoms (quantified using questionnaires)[13]

,[14]

,[15]

,[16]

,[17]

,[18]

,[19]

,[20]

,[21]

,[22]

. Information on how pharmacists and pharmacy teams can identify and diagnose patients with dry eye can be found in a previous learning article[23]

.

As the disease process has become better understood, increased importance has been placed on the key features of the disease; hyperosmolarity, instability and cell damage[24]

. The assessment of osmolarity has proved to be a key component to diagnose dry eye disease since a clinical instrument became available[13]

,[19]

,[22]

,[25]

,[26]

,[27]

,[28]

,[29]

. Sensitivity and specificity of any diagnostic test depends on the ‘disease’ group criteria (severity, inclusion and exclusion criteria and instrumentation), invariably causing bias (spectrum, sampling and selection bias, respectively)[24]

. For that reason, a level of pragmatism is needed, as well as reviewing clinical research, to determine the most appropriate test algorithm to apply.

The TFOS DEWS II report states that symptoms must be present (as required by the definition) and these should be identified by one of two well-validated questionnaires — the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI, 12 questions)[30]

or the Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5 item)[31]

. Both of these are short, and could easily form part of a patient interaction and consultation in a pharmacy setting.

Having identified that a patient has symptoms above the threshold level (≥13 on OSDI) or ≥6 on DEQ-5), one of tear film instability (non-invasive breakup time), hyperosmolarity or ocular surface damage needs to be observed to confirm the lack of homeostasis of the tear film element described in the definition. If a diagnosis is confirmed with positive test result(s), the sub-classification of dry eye can be determined (as predominantly evaporative or predominantly aqueous deficient) by evaluating meibomian gland dysfunction[32]

, lipid thickness/dynamics and tear volume. This further testing helps to inform the management of dry eye disease. It is rare for any of these clinical tests to be available in a pharmacy setting, and referral to a specialist optometric or ophthalmological clinic will be required for diagnostic confirmation.

Therefore, pharmacists and pharmacy teams have a role, prior to establishing the diagnosis, to ensure that more serious ocular pathologies, which might include some of the symptoms of dry eye disease, are not masked by inappropriate temporary relief of symptoms such as using artificial tears.

The key questions for pharmacists to ask as part of their differential diagnosis have been identified by the TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology Committee and are presented in Table 2[24]

. If any of these questions identify a non-standard dry eye disease response, a semi-urgent referral to an optometrist or ophthalmologist is warranted to exclude other pathology.

| Table 2: Initial questions for the differential diagnosis of dry eye disease, indicating where more detailed observation of the ocular surface and adnexa is warranted | |

|---|---|

| Medications that can cause DED are noted in the TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report[1] . Sjögren’s syndrome is a subtype of DED, but is included in the differential diagnosis questioning to ensure it is considered from the outset, due to the associated co-morbidities[33] . | |

| How severe is the eye discomfort? | Unless severe, dry eye presents with signs of irritation such as dryness and grittiness rather than pain. If pain is present, investigate for signs of trauma, infection and ulceration |

| Do you have any mouth dryness or enlarged glands? | Trigger for Sjögren’s syndrome investigation |

| How long have your symptoms lasted and was there any triggering event? | Dry eye is a chronic condition, present from morning to evening but is generally worse at the end of the day, so if sudden onset or linked with an event, examine for trauma, infection and ulceration |

| Is your vision affected and does it clear on blinking? | Vision is generally impaired with prolonged staring, but should largely recover after a blink; a reduction in vision which does not improve with blinking, particularly with sudden onset, requires an urgent opthalmic examination |

| Are the symptoms or any redness much worse in one eye than the other? | Dry eye is generally a bilateral condition, so if symptoms or redness are much greater in one eye than the other, detailed eye examination is required to exclude trauma and infection |

| Do the eyes itch, are they swollen, crusty or have they given off any discharge? | Itching is usually assocaited with allergies, while a mucopurulent discharge is associated with ocular infection |

| Do you wear contact lenses? | Contact lenses can induce dry eye signs and symptoms and appropriate management strategies should be employed by the contact lens prescriber |

| Have you been diagnosed with any general health conditions (including recent respiratory infections) or are you taking any medications? | Patients should be advised to mention their symptoms to the health professionals managing their condition, as modified treatment may minimise or alleviate their dry eye |

Treatment

The ultimate aim of dry eye management is to restore homeostasis of the ocular surface[34]

. While there are treatments that may be specifically indicated for one particular aspect of an individual patient’s ocular surface condition, many treatments are appropriately recommended for multiple aspects of dry eye disease.

The management of dry eye disease typically involves dealing with chronic sequelae that require ongoing management, rather than attempting to provide a short-term treatment, if dry eye issues are to be significantly reduced. The mainstay of dry eye disease management is provision of advice on modifiable risk factors (e.g. nutrition and the environment), tear enhancement (e.g. ocular lubricants), tear preservation (e.g. punctal plugs and humidity goggles), tear stimulation (e.g. secretagogues), eyelid management (e.g. lid hygiene and gland warming/massage) and pharmaceutical approaches (e.g. antibiotics and steroids). Information on how community pharmacists and pharmacy teams can best manage patients with dry eye conditions, including recommending treatments, is covered in a previous learning article[9]

.

Pharmacists should advise patients on keeping hydrated, eating well (especially including essential fatty acid omega 3 in their diet or taking supplements, unless contraindicated), taking regular breaks from high concentration near-work tasks (e.g. using digital devices), avoiding unnecessary systemic or preserved topical medication, and minimising exposure to adverse environmental conditions (e.g. low humidity, extreme temperatures, moving air or air pollution).

If the patient is a contact lens wearer and has symptoms exacerbated or induced by the use of lenses, they should be advised to return to their optometrist or optician to try options to alleviate this issue[35]

.

EDE can often be managed in a pharmacy setting by recommending hot compresses (commercial solutions vary in their efficacy so the effectiveness should be established before recommendation) lipid drops and liposomal sprays. If blepharitis is evident (dandruff-like scales of dead skin at the base of eyelashes), then the use of eyelid cleansers (often called lid wipes) is more effective and safer than the formerly recommended ‘baby shampoo’ management[36]

.

ADDE is generally managed with artificial tears that increase the retention of moisture on the ocular surface between blinks. There are relatively few randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that have compared the relative superiority of a particular product to others for dry eye disease to inform between the wide range available[37]

,[38]

.

Patients should be advised that dry eye disease management is an ongoing process and that they should return if they have not achieved sufficient relief within one and three months of trialling a new treatment.

Pharmacists are often the first port of call for many patients with dry eye disease and are important gatekeepers to the management of this chronic debilitating condition, although research shows a higher level of education and care of approach is needed[39]

.

Useful resources:

- Tear Film and Ocular Surface website

- Includes videos showing the best way to conduct dry eye disease diagnostic and management techniques

-

The Pharmaceutical Journal supplement. Focus: Dry eye - Pharmacy Learning Centre: Eye Care

Declarations of interest:

Jennifer Craig and James Wolffsohn are both board members of the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society and chaired some of the sub-committees of the second Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS II). Both are active researchers in the field of dry eye and receive funding to conduct research from a large number of companies involved in this sector.

RB provided financial support in the production of this content. The Pharmaceutical Journal retains full editorial control.

UK/O/0717/0033d

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Stapleton FJ, Alves M, Bunya V et al. TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report. Ocul Surf 2017;15(3):334–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.003

[2] Lawrence J. Multidisciplinary panel of experts agree on best treatment of dry eye conditions in community pharmacy. Pharm J suppl, Focus on Dry Eye. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/pharmacy-learning-centre/multidisciplinary-panel-of-experts-agree-on-best-treatment-of-dry-eye-conditions-in-community-pharmacy/20201187.article (accessed September 2017)

[3] Nelson JD, Craig JP, Akpek E et al. TFOS DEWS II: Introduction. Ocul Surf 2017;15(3):269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.005

[4] Lemp MA. Report of the National eye institute/ industry workshop on clinical trials in dry eyes. CLAO J 1995;21(4):221–232. PMID: 8565190

[5] The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf 2007;5(2):75–92. doi: 10.1016/S1542-0124(12)70081-2

[6] Connelly D. Dry eye: pathology and treatment types. Pharm J suppl, Focus on Dry Eye. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/pharmacy-learning-centre/dry-eye-pathology-and-treatment-types/20201582.article (accessed September 2017)

[7] Bron AJ, de Paiva CS, Chauhan S et al. TFOS DEWS II: pathophysiology report. Ocul Surf 2017;15(3):438–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.011

[8] Gomes JAP, Azar DT, Baudouin C et al. TFOS DEWS II: iatrogenic dry eye report. Ocul Surf 2017;15(3):511–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.004

[9] Evans K & Madden L. Recommending dry eye treatments in community pharmacy. Pharm J suppl, Focus on Dry Eye. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/pharmacy-learning-centre/recommending-dry-eye-treatments-in-community-pharmacy/20201430.article (accessed September 2017)

[10] Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek E et al. TFOS DEWS II: definition and classification report. Ocul Surf 2017;15(3):276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.008

[11] Methodologies to diagnose and monitor dry eye disease: report of the Diagnostic Methodology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf 2007;5(2):108–152. doi: 10.1016/S1542-0124(12)70083-6

[12] Lemp MA, Crews LA, Bron AJ et al. Distribution of aqueous-deficient and evaporative dry eye in a clinic-based patient cohort: a retrospective study. Cornea 2012;31(5):472–478. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318225415a

[13] Amparo F, Jin Y, Hamrah P et al. What is the value of incorporating tear osmolarity measurement in assessing patient response to therapy in dry eye disease? Am J Ophthalmol 2014;157(1):69–77 e62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.07.019

[14] Baudouin C, Aragona P, Van Setten G et al. Members OECG. Diagnosing the severity of dry eye: a clear and practical algorithm. Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98(9):1168–1176. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304619

[15] Chalmers RL, Begley CG & Caffery B. Validation of the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5): Discrimination across self-assessed severity and aqueous tear deficient dry eye diagnoses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2010;33(2):55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2009.12.010

[16] de Monchy I, Gendron G, Miceli C et al. Combination of the Schirmer I and phenol red thread tests as a rescue strategy for diagnosis of ocular dryness associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52(8):5167–5173. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6671

[17] Graham JE, McGilligan VE, Berrar D et al. Attitudes towards diagnostic tests and therapies for dry eye disease. Ophthalmic Res 2010;43(1):11–17. doi: 10.1159/000246573

[18] Kallarackal GU, Ansari EA, Amos N et al. A comparative study to assess the clinical use of Fluorescein Meniscus Time (FMT) with Tear Break up Time (TBUT) and Schirmer’s tests (ST) in the diagnosis of dry eyes. Eye (Lond) 2002;16(5):594–600. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700177

[19] Lemp MA, Bron AJ, Baudouin C et al. Tear osmolarity in the diagnosis and management of dry eye disease. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151(5):792–798 e791. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.10.032

[20] Mainstone JC, Bruce AS & Golding TR. Tear meniscus measurement in the diagnosis of dry eye. Curr Eye Res 1996;15(6):653–661. PMID: 8670769

[21] Shen M, Li J, Wang J et al. Upper and lower tear menisci in the diagnosis of dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009;50(6):2722–2726. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2704

[22] Sullivan BD, Crews LA, Messmer EM et al. Correlations between commonly used objective signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of dry eye disease: clinical implications. Acta Ophthalmol 2014;92(2):161–166. doi: 10.1111/aos.12012

[23] Wolffsohn JS. Identification of dry eye conditions in community pharmacy. Pharm J suppl, Focus on Dry Eye. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/pharmacy-learning-centre/identification-of-dry-eye-conditions-in-community-pharmacy/20201138.article (accessed September 2017)

[24] Wolffsohn JS, Chalmers R, Djalilian A et al. TFOS DEWS II: Diagnostic Methodology Report. Ocular Surface 2017;15(3):539–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.001

[25] Bunya VY, Fuerst NM, Pistilli M et al. Variability of Tear Osmolarity in Patients With Dry Eye. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015;133(6):662–667. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.0429

[26] Potvin R, Makari S & Rapuano CJ. Tear film osmolarity and dry eye disease: a review of the literature. Clin Ophthalmol 2015;9:2039–2047. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S95242

[27] Szalai E, Berta A, Szekanecz Z et al. Evaluation of tear osmolarity in non-Sjögren and Sjögren’s syndrome dry eye patients with the TearLab system. Cornea 2012;31(8):867–871. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182532047

[28] Tomlinson A, Khanal S, Ramaesh K et al. Tear film osmolarity: determination of a referent for dry eye diagnosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47(10):4309–4315. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1504

[29] Versura P, Profazio V & Campos EC. Performance of tear osmolarity compared to previous diagnostic tests for dry eye diseases. Curr Eye Res 2010;35(7):553–564. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2010.484557

[30] Allergen. Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire. 1995. Available at: http://www.dryeyezone.com/documents/osdi.pdf (accessed September 2017)

[31] The 5-item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5). Available at: https://www.dovepress.com/cr_data/article_fulltext/s80000/80043/img/OPTH-80043-F03.png (accessed September 2017)

[32] Tomlinson A, Bron AJ, Korb DR et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the diagnosis subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52(4):2006–2049. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997f

[33] Shiboski SC, Shiboski CH, Criswell L et al. Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance Research G. American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a data-driven, expert consensus approach in the Sjögren’s International Collaborative Clinical Alliance cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(4):475–487. PMC3349440

[34] Jones L, Downie LE, Korb DR et al. TFOS DEWS II: management and therapy report. Ocul Surf 2017;15(3):575–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.006

[35] Papas EB, Ciolino JB, Jacobs D et al. The TFOS international workshop on contact lens discomfort: report of the management and therapy subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54(11):Tfos183–203. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13166

[36] Craig JP, Wang MT, Cheung I et al. Commercial lid cleanser outperforms baby shampoo for management of blepharitis in randomized, double-masked clinical trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017;Meeting abstract(Program Number:2247)

[37] Downie LE & Keller PR. A pragmatic approach to the management of dry eye disease: evidence into practice. Optom Vis Sci 2015;92(9):957–966. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000653

[38] Pucker AD, Ng SM & Nichols JJ. Over the counter (OTC) artificial tear drops for dry eye syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2:CD009729. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009729.pub2

[39] Bilkhu PS, Wolffsohn JS, Tang GW et al. Management of dry eye in UK pharmacies. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2014;37(5):382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2014.06.002