Phanie / Alamy Stock Photo

Many people express a preference to be cared for, and die in their own home, or in their usual place of residence[1]

,[2]

,[3]

,[4]

,[5]

,[6]

. Respecting a patient’s wishes about their preferred place of care is a vital contributory factor to achieving a good death[4]

,[5]

,[6]

,[7]

. As death approaches, some patients change their preferences to reduce the burden on family members, or because their symptoms have not been adequately managed at home[3],[6],[7]

. Although place of death has become a key indicator of the quality of end-of-life care[1]

, it is recognised that dying at home is not appropriate for all[6]

. A good death is dependent on good symptom management, compassionate individualised care and comprehension of what is important to the dying patient[7]

,[8]

,[9]

,[10]

,[11]

. Improving access to community palliative care services is key to supporting a patient’s wish to die at home

[3].

End-of-life care and anticipatory prescribing

End-of-life care is formally defined as ‘palliative care given within the last year of life’ but frequently refers to care in the last days of life[12]

.

An important consideration is the need to anticipate what symptoms the patient is likely to experience as they approach the end of their life and to ensure that there is immediate access to necessary medications. Prescribing medications in anticipation of need can avoid lapses in symptom control and the associated distress this can cause to the dying patient and to those important to them[11]

,[13]

,[14]

,[15]

,[16]

,[17]

,[18]

.

Anticipatory prescribing can be defined as the proactive prescribing of medicines that are commonly required to control symptoms in the last days of life. This process of anticipatory prescribing can be described as four distinct stages[19]

,[20]

:

- Initiating the conversation with the patient and their family;

- Writing the prescription;

- Dispensing the medicines;

- Administering the medicines to the patient.

Community nurses and nurses in care homes frequently play an ongoing and prominent role in end-of-life care. They are ideally placed to recognise and diagnose when patients are nearing the end-of-life, in order to initiate appropriate discussions related to end-of-life care, including anticipatory medication for symptom control, with the patient and their family[18]

,[20]

,[21]

. Nurses also have a key role in activating anticipatory prescriptions[11],[18]

.

The prescription for anticipatory medicines is usually written by the GP, although it may be written by an independent non-medical prescriber, if it is within their area of competence and practice. The prescription is dispensed for the individual patient by a community pharmacy in accordance with current legislation. The medicines are then kept in the patient’s home, often in a ‘Just in case’ (JIC) box (see Box 1 for typical contents), for immediate access to symptom control should the patient’s condition change.

These medicines are administered by a healthcare professional, most commonly a nurse. In certain circumstances it may be appropriate for a family member to administer specific medications. In those instances, clear instructions are imperative.

Symptoms that are most likely to present as patients near the end of their life include pain, nausea and vomiting, delirium and agitation, terminal restlessness, and respiratory secretions[8],[14]

,[15]

,[

22]

. Medicines for each of these symptoms should be prescribed in anticipation of need according to local guidelines. The medicines, doses and quantities prescribed will vary depending on local policy, geographical area and individual patient requirements. Patients with non-malignant disease present specific challenges and may require additional medications or modification to standard medicines or doses[19]

,[23]

. Table 1 provides an example of an anticipatory prescription.

| Action | Medication | Subcutaneous (SC) dose | Indication | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesic | Morphine sulfate | 2mg* SC hourly as needed (*opioid naive patient) | Pain or breathlessness | 5 x 10mg/ml ampoules |

| Anxiolytic sedative | Midazolam | 2mg SC hourly as needed | Anxiety, distress, myoclonus | 10 x 10mg/2ml ampoules |

| Anti-secretory | Hyoscine butylbromide | 20mg SC hourly as needed (maximum of 120mg in 24hrs) | Respiratory secretions | 10 x 20mg/ml ampoules |

| Anti-emetic | Levomepromazine | 2.5mg to 5mg SC 8–12 hourly as needed | Nausea, vomiting | 10 x 25mg/ml ampoules |

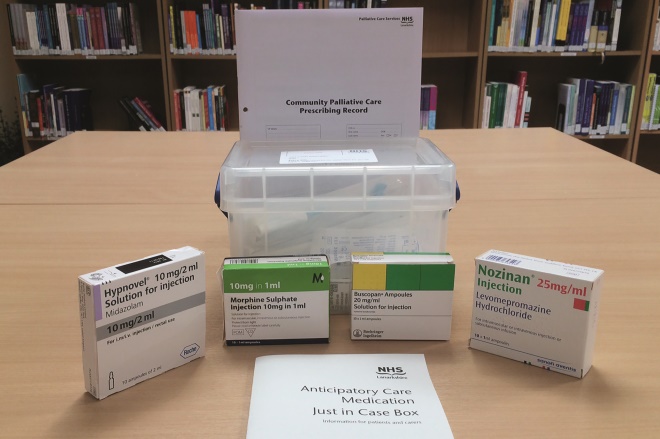

Just in case boxes

Across the UK many areas have implemented JIC box initiatives to support anticipatory prescribing[17]

,[24]

,[25]

,[26]

,[27]

. The dispensed anticipatory medicines are stored in a readily identifiable container along with the appropriate equipment and the necessary documentation to facilitate prompt administration if symptoms develop[15]

,[24]

. To ensure the security of the box while in the patient’s home, procedures should be in place to minimise the risk of medicines being unlawfully diverted[24]

.

Source: Courtesy of Linda Johnstone

Many areas of the UK have implemented ’Just in case’ box initiatives to support anticipatory prescribing. Dispensed anticipatory medicines, equipment and documentation are stored in an identifiable container to facilitate prompt administration (see image).

The decision to prescribe medications in anticipation of need should always be based on risk/benefit analysis, taking into consideration individual family circumstances[14]

. As the medications are prescribed for the patient, they belong to the patient and have the same legal status as other prescribed drugs[28]

.

The presence of a JIC box provides reassurance to the patient and their family that symptoms can be managed with minimal delay in the home, avoiding unnecessary distress[25]

,[26]

. As patients near the end-of-life, their condition can change rapidly and the presence of a JIC box can prevent unnecessary calls to the out-of-hours service or a crisis admission to hospital[13]

. The results of a 2010–2011 audit of JIC boxes in NHS Lanarkshire indicated that 180 JIC boxes were used for symptom management, while 39 were not required. Having JIC boxes in the home was found to have prevented 114 calls to the out-of-hours service and averted 84 hospital admissions. Annual costs of £359,000 were estimated to be avoided but, more importantly, patients were able to die peacefully at home rather than experiencing distressing symptoms while waiting for a doctor or hospital admission[29]

.

Further guidance and best practice on anticipatory prescribing for end-of-life care has been produced by the British Medical Association. A summary is included in Box 2.

Box 1: Contents of a typical ‘just in case’ box

- Anticipatory medicines for subcutaneous use (including diluent);

- Needles and syringes;

- Prescribing guidance;

- Authorisation to administer medication document;

- Patient and carer information leaflet;

- Contact details for advice.

Box 2: British Medical Association guidance for best practice

The prescriber must accept responsibility for prescribing in anticipation of need and be mindful that the availability of medication does not replace the need for clinical assessment when the patient’s clinical condition changes:

- Agree the list of anticipatory medicines locally with key stakeholders;

- Reduce the risk of prescription errors by agreeing the recommended starting doses and making them readily available to prescribers on pre-printed sheets;

- Balance the quantity supplied between adequate supply and potential waste;

- Include equipment and documentation to facilitate the administration of medicines in the just in case box;

- Be self-assured that the patient and carers understand the rationale for placing medicines in the home;

- Ensure that all healthcare professionals involved in the care of the patient are aware of the clinical situation and the availability of anticipatory medicines, including those providing the out-of-hours service.

Challenges

Although the value of anticipatory prescribing is well recognised, the process can present challenges at any of the stages. Diagnosing when patients are nearing death can be difficult, particularly in patients with non-malignant disease and an unpredictable disease trajectory[30]

. Difficulties in diagnosing dying can result in patients suffering from underprescribing of anticipatory medicines[31]

. Anticipatory medicines also need to be modified for people dying from non-malignant disease, such as the frail older patient with multiple morbidities[23]

.

GPs may be reluctant to prescribe medicines where they have diminished control over administration[11]

,[21],[32]

. Writing a correct and valid prescription can be problematic if the prescriber lacks adequate knowledge of the medicines and their legal status. Prescriptions that are incorrectly written can result in significant delays in supply, particularly during the out-of-hours period and when controlled drugs are prescribed[32]

.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that anticipatory medicines are placed in the home as early as possible[8]

. However, medicines may expire before they are required if requested too far in advance. The presence of children or vulnerable adults in the home can raise concerns regarding safe storage, especially if anticipatory medicines are kept for extended periods of time. The potential for misuse or unlawful diversion is an ongoing risk that must be given careful deliberation.

The responsibility for administration and monitoring of anticipatory medicines is frequently borne by community nurses[33]

. Nurses can feel burdened by the decisions placed on them and can lack the experience and support to distinguish between symptoms and evaluate the effectiveness of the administered medication with confidence[19]

,[20]

,[21],[32]

. Healthcare professionals require a clear understanding of each other’s responsibilities in the anticipatory prescribing process and established relationships that support trust in decision making[32]

. Discussing end-of-life care and symptom management can be an emotionally challenging time for all concerned and it is vital that healthcare professionals develop the necessary communication skills to do so — a useful learning article was published in this journal earlier in the year[34]

.

Practical tips for pharmacists and other healthcare professionals

Before prescribing anticipatory medicines the prescriber should check whether the patient is already receiving subcutaneous (SC) medications. Only those medicines that are not already in the home should be prescribed for this purpose.

Many pharmacies have contracted local agreements to stock a defined list of palliative care medicines and often have extended opening hours. Healthcare professionals should be aware of the pharmacies that provide this service in their local area. Patients and carers should be made aware of the urgency of the prescription to avoid unnecessary distress if the medicine cannot be supplied immediately.

Following a patient’s death, any unused medicines should be returned to a community pharmacy for safe disposal. Possession of a controlled drug by someone other than the person for whom it was dispensed is illegal.

Healthcare professionals who are involved in the anticipatory prescribing process should identify their own educational needs to ensure key palliative care competencies, such as symptom management and sensitive communication with patients and families[34]

, are attained and maintained.

Specialist palliative care services should be utilised for additional support, for example, 24-hour advice helplines may be provided by local specialist palliative care units.

A good relationship between the patient and their family and the primary healthcare team is paramount to achieving high quality end-of-life care and a good death. Healthcare professionals should strive to build effective trusting relationships, particularly with colleagues in the out-of-hours service, to ensure that those providing end-of-life care are aware of the clinical status of the patient and the availability of anticipatory medicines in the home.

How this article can contribute to your own continued professional development (CPD)

Reading this article and by reflecting on what you have learnt and how it may support your professional development, contributes to your CPD as a pharmacist. Now you have read this learning article, please consider the following:

- What did you learn?

- What knowledge, skills, attitudes or competencies have you developed, improved or reinforced?

- How do you feel this learning has changed or will change your practice?

- What further learning or development needs do you have as a result of this activity?

Useful resources

1. NHS Inform: ‘Just in Case’ medicines

2. Scottish palliative care guidelines

3. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: palliative care

4. End of Life Care Core Skills Education and Training Framework. NHS Health Education England

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Department of Health. End-of-life care strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the end-of-life. July 2008. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/136431/End_of_life_strategy.pdf (accessed May 2017)

[2] The National End of Life Care Intelligence Network. What we know now 2014. Public Health England 2015. Available at: http://www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk/resources/publications/what_we_know_now_2014 (accessed May 2017)

[3] Dixon J, King D, Matosevic T et al. Equity in the provision of palliative care in the UK: Review of evidence. Personal Social Services Research Unit, London School of Economics and Political Science. 2015. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/61550/1/equity_in_the_provision_of_paliative_care.pdf (accessed May 2017)

[4] Capel M, Gazi T, Vout L et al. Where do patients known to a community service die? BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2012;2:43–47. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000097

[5] Ali M, Capel M, Jones G et al. The importance of identifying preferred place of death. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2015;0:1-8. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000878

[6] Pollock K. Is home always the best and preferred place of death? BMJ 2015;351:h4855. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4855

[7] Sherwen E. Improving end-of-life care for adults. Nursing Standard 2014;28(32):51–57. doi: 10.7748/ns2014.04.28.32.51.e8562

[8] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE guideline—Care of dying adults in the last days of life (NG31). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng31 (accessed May 2017)

[9] Hodgkinson S, Ruegger, Field-Smith A et al. Care of dying adults in the last days of life. Clin Med 2016;16(3):254–258. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-3-254

[10] Leadership Alliance for the Care of Dying People. One chance to get it right: improving people’s experience of care in the last few days and hours of life. 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/323188/One_chance_to_get_it_right.pdf (accessed May 2017)

[11] Karlsson C & Berggren I. Dignified end-of-life care in the patient’s own homes. Nurs Ethics 2011;18(3):374–385. doi: 10.1177/0969733011398100

[12] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE Quality standard—End of life care for adults (QS13). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2011. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs13/chapter/introduction-and-overview (accessed May 2017)

[13] Scottish Government. Living and dying well: a national action plan for palliative and end-of-life care in Scotland. 2008. Available at: http://www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/239823/0066155.pdf (accessed May 2017)

[14] Scottish Palliative Care Guidelines. Anticipatory Prescribing. NHS Scotland. Health Improvement Scotland. 2014. Available at: http://www.palliativecareguidelines.scot.nhs.uk/guidelines/pain/Anticipatory-Prescribing.aspx (accessed May 2017)

[15] Wilcock A & Twycross R. Pre-emptive prescribing in the community. Palliative Care Formulary (PCF5). Available at: http://www.palliativedrugs.com/assets/pcf5/PCF5_sample_prelims.pdf (accessed May 2017)

[16] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE quality standard—Care of dying adults in the last days of life. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/QS144/documents/draft-quality-standard (accessed May 2017)

[17] Ogden J. Anticipatory prescribing for end of life care. Prescriber 2016;46–49. doi: 10.1002/psb.1499

[18] Griffiths J, Ewing G, Wilson C et al. Breaking bad news about transitions to dying: A qualitative exploration of the role of the district nurse. Palliative Medicine 2015;29(2):138–146. doi: 10.1177/0269216314551813

[19] Faull C, Windridge K, Ockleford E et al. Anticipatory prescribing in terminal care at home: what challenges do community health professionals encounter? BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2013;3:91–97. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000193

[20] Wilson E, Morbey H, Brown H et al. Administering anticipatory medications in end-of-life care: A qualitative study of nursing practice in the community and in nursing homes. Palliative Med 2015;29(1):60–70. doi: 10.1177/0269216314543042

[21] Wilson E, Seymour J & Seale C. Anticipatory prescribing for end of life care: a survey of community nurses in England. Primary Health Care 2016;26(9):22–27. doi: 10.7748/phc.2016.e1151

[22] Chand S. Dealing with the dying patient—treatment of terminal restlessness. Pharm J 2013;290:382. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2013.11119466

[23] Kinley J, Stone L & Hockley J. Anticipatory end-of-life care medication for the symptoms of terminal restlessness, pain and excessive secretions in frail older people in care homes. End of Life J 2013;3(3):1–6. doi: 10.1136/eoljnl-03-03.5

[24] The Gold Standards Framework. Examples of good practice resource guide—Just in case boxes. August 2006. Available at: http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/cd-content/uploads/files/Library%2C%20Tools%20%26%20resources/ExamplesOfGoodPracticeResourceGuideJustInCaseBoxes.pdf (accessed May 2017)

[25] Lawton S, Denholm M, Macaulay L et al. Timely symptom management at end of life using ‘just in case’ boxes. Br J Community Nurs 2012;17(4):182–190. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2012.17.4.182

[26] Amass C & Allen M. How a ‘just in case’ approach can improve out-of-hours palliative care. Pharm J 2005;275:22–23. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/opinion/comment/how-a-just-in-case-approach-can-improve-out-of-hours-palliative-care/10019364.fullarticle (accessed May 2017)

[27] Jamal H, Brown R & Allan R. Just in case EOL drugs in patients’ homes—prescribing and outcomes in a cancer network. Palliative Med 2014; 28(6). Astract: P313. Available at: https://insights.ovid.com/palliative-medicine/plmd/2014/06/000/just-case-eol-drugs-patients-homes-prescribing/452/00019505 (accessed May 2017)

[28] British Medical Association. Focus on anticipatory prescribing for end-of-life care. General Practitioners Committee guidance. April 2012. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice/employment/gp-practices/service-provision/prescribing/focus-on-anticipatory-prescribing-for-end-of-life-care (accessed May 2017)

[29] Dunn R, Johnstone L & Smith J. Anticipatory prescribing for dying patients—A pilot study of Just in Case boxes in NHS Lanarkshire. Available at: https://www.palliativecarescotland.org.uk/content/publications/14.-Anticipatory-prescribing-for-dying-patients.pdf (accessed May 2017)

[30] Dalkin SM, Lhussier M, Philipson P et al. Reducing inequalities in care for patients with non-malignant diseases: Insights from a realist evaluation of an integrated palliative care pathway. Palliative Med 2016;30(7):690–697. doi: 10.1177/0269216315626352

[31] Finucane A, McArthur D, Stevenson B et al. Anticipatory prescribing at the end of life in Lothian Care Homes. Br J Community Nurs 2014;19(11):544–547. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2014.19.11.544

[32] Wilson E & Seymour J. The importance of interdisciplinary communication in the process of anticipatory prescribing. Int J Palliative Nurs 2017;23(3):129–135. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2017.23.3.129

[33] Eisenhauer L, Hurley A & Dolan N. Nurses’ reported thinking during medication administration. J Nurs Scholarship 2007;39(1):82–87. PMID: 17393971

[34] Archer A, Latif A & Faull C. Communicating with palliative care patients nearing the end of life, their families and carers. Pharm J 2017;298(7897). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2017.20202154

You might also be interested in…

Government to ‘strengthen’ out-of-hours support for palliative care services

Support for pharmacies providing palliative care urged as hospices get cash injection