Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand the mechanism of action of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) analogues;

- Understand the place in therapy of GLP-1 and GIP analogues for glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus;

- Be aware of the cautions, contraindications and side effects for the GLP-1 and GIP analogues.

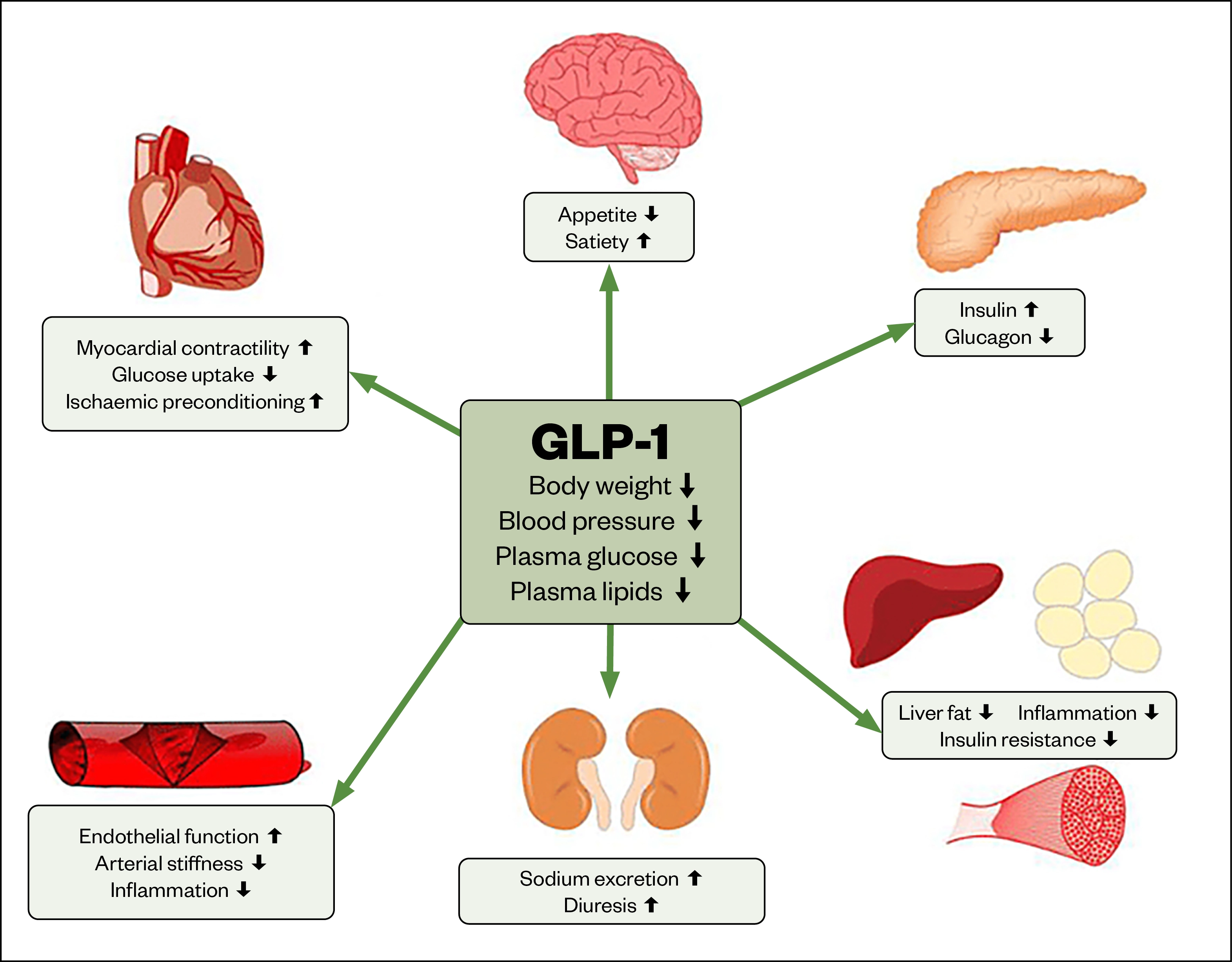

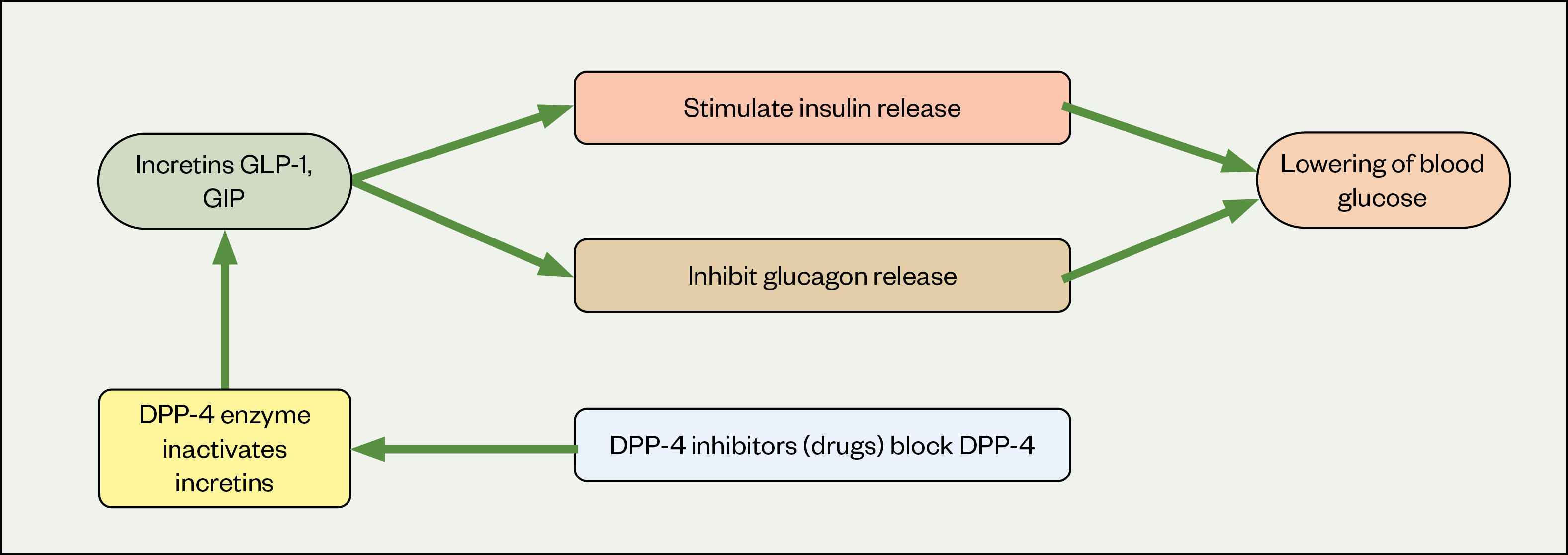

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulionotropic polypeptide (GIP) are intestinal incretin hormones that are released from the distal ileum and colon in response to food intake. GLP-1 and GIP play an important role in glucose homeostasis, stimulating insulin release and inhibiting glucagon release, resulting in a lowering of blood glucose. GLP-1 and GIP also have extra pancreatic effects, which include a slowing of gastric emptying and central effects on the brain, leading to satiety and reduced appetite[1]. Figures 1 and 2 show the normal function of GLP-1 in human health and the mechanism by how it exerts these effects[2]. In people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), this secretion is impaired, thus disrupting normal homeostasis and resulting in increases in blood glucose level[3]. This discovery has led to the development of GLP-1 analogues for treatment of T2DM.

GLP-1 analogues may be referred to as GLP-1 agonists or GLP-1 mimetics. GLP-1 agonists bind to and activate GLP-1 receptors to increase insulin secretion, suppress glucagon secretion and slow gastric emptying[4].

This article outlines the place of GLP-1 and GIP analogues in wider therapy, while also highlighting relevant cautions, contraindications and side effects, with the aim of supporting safe prescribing and use of GLP-1 and GIP analogues for glycaemic control in adults with T2DM.

Overview of available GLP-1 analogues

GLP-1 analogues are classified based on whether the backbone of the compound is human (e.g. dulaglutide, liraglutide or semaglutide) or exendin-derived (e.g. exenatide or lixisenatide)[5–11]. Exendin is a peptide-1 receptor agonist protein typically found and produced in the gut of desert-dwelling reptiles[12]. GLP-1 analogues differ in their duration of action, respective half-lives and route of administration and therefore require different frequencies of administration (see Figure 3).

Available GLP-1 and GIP1 analogues

Tirzepatide (Mounjaro; Eli Lilly and Co) is a first in class long-acting dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide GIP/GLP-1 RA for the treatment of T2DM in adults. This means tirzepatide is the first agent to be develop that targets both GIP and GLP-1 hormones. There is currently no other agent on the market for the treatment of diabetes that works by this mechanism of action. This unique mechanism of action has earned tirzepatide the nickname ‘twincretin’.

Who is likely to benefit from GLP-1 and GIP therapy?

As with any pharmacological therapy, it is important that GLP-1 and GIP therapy is given to those who are most likely to benefit.

GLP-1 and GIP therapy should be considered in people with indicators of high risk or established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). The American Diabetes Association classification of high ASCVD risk, which is widely accepted in the UK, is:

- Age 55 years or older;

- Coronary, carotid or lower extremity stenosis >50%;

- Left ventricular hypertrophy;

- Estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 or albuminuria[13].

Therapy should also be considered in those with a compelling need to minimise weight gain or lose weight, because the links between diabetes and obesity are well known. For example, there is a seven times greater risk of diabetes in obese people compared to those of healthy weight, with a three-fold increase in risk for overweight people[14].

What are the initiation criteria for GLP-1 and GIP therapy?

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) criteria for initiation of GLP-1 and GIP analogues is as follows: if triple therapy with metformin and two other oral drugs is not effective, not tolerated or contraindicated, consider triple therapy by switching one drug for a GLP-1 analogues for adults with T2DM who have a body mass index (BMI) of 35kg/m2 or higher[15]. This should be adjusted to a BMI of 25kg/m2 for people from black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups as evidence suggests that these groups are at a higher risk of diabetes and other health conditions than white populations at a lower BMI[16]. As a consequence, lower cut-off points in these patient groups may be appropriate. Additional information on how this adjustment can be managed can be found here[16].

It is worth being aware that several GLP-1s are also licensed for weight management[17]. This aspect is beyond the scope of this article. However, individuals who have type 2 diabetes alongside a need to minimise weight gain or promote weight loss may benefit from GLP-1/GIP therapy and its dual impact on type 2 diabetes management and weight loss.

Therapy should also be considered in individuals who have specific psychological conditions or other comorbidities associated with obesity; for example, coronary heart disease, or in those that have a BMI lower than 35kg/m2 and for whom insulin therapy would have significant occupational implications[15]. For example, people who work shifts and therefore may have irregular eating and sleeping patterns, or people who drive for a living, as they may find that insulin use impacts their insurance premium and livelihood.

It should be noted that the NICE criteria differ to that of some of the individual medications licensing and the drugs have been positioned as this following NICE appraisal and review of many factors including usage, benefit and cost analysis.

A GLP-1 and GIP analogue should only be offered to adults with T2DM, in combination with insulin with specialist care advice and ongoing support from a consultant-led multidisciplinary team.

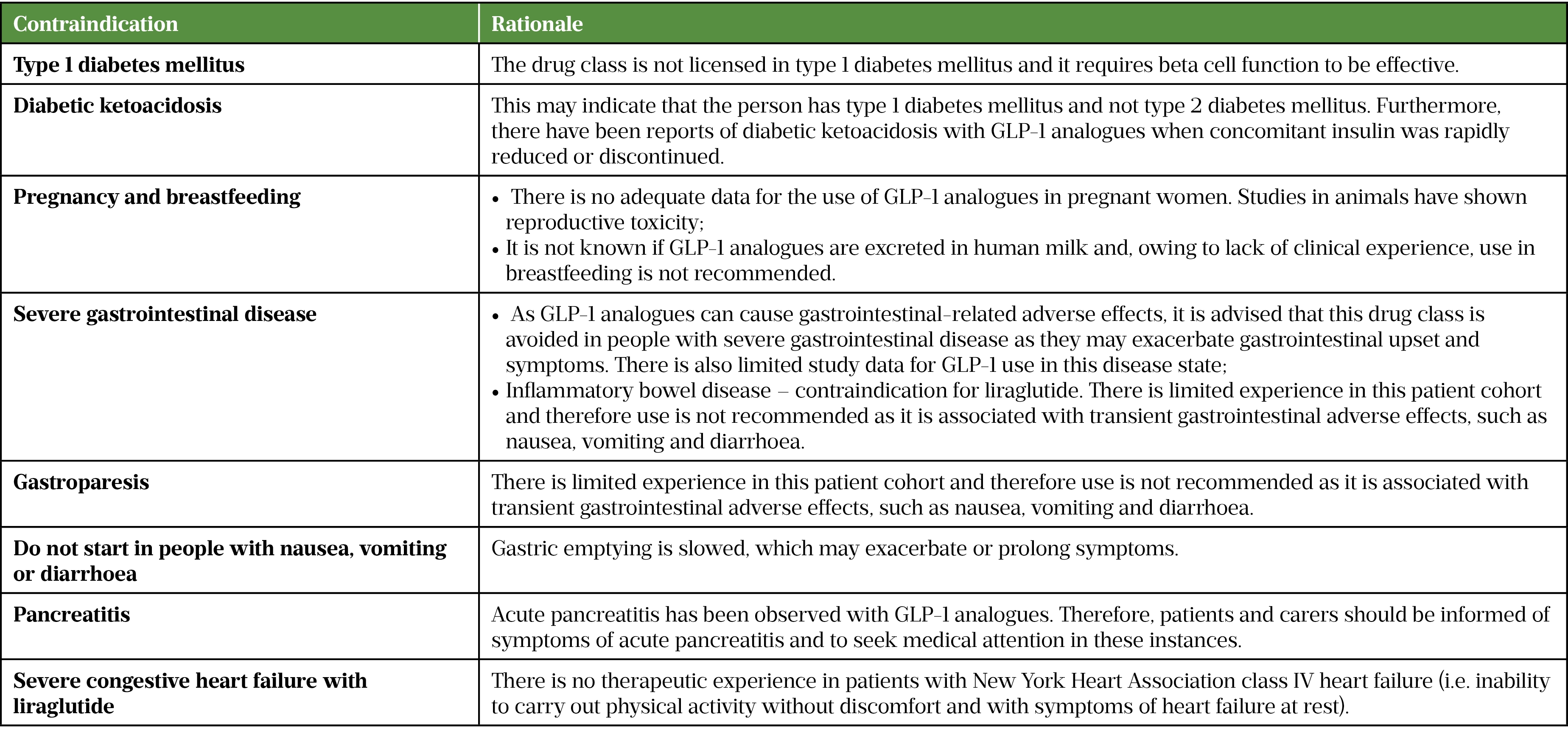

See Table 1 for which patient groups should not receive GLP-1 therapy[5–11,18]

Cautions for GLP-1 and GIP therapy use

GLP-1 and GIP therapy should be used with caution in certain patient groups. For example, more cautious dose titration is recommended in older people owing to increased risk of hypoglycaemia and limited evidence and experience initiating GLP-1 and GIP analogues in people aged over 75 years. Pharmacists may wish to lengthen the duration between starting dose and dose increase, and should routinely check the summary of product characteristics (SPC) for individual drugs for more information. Additional vigilance is required in individuals with a family history of, or risk factors for, pancreatitis — these include high alcohol intake, gallstones, and high triglycerides[5–11].

Rapid improvement in glucose control (e.g. with insulin and GLP-1 and GIP analogues) has been associated with temporary worsening of diabetic retinopathy (disease of the retina secondary to diabetes)[19]. Semaglutide should be used with caution in patients taking insulin owing to the increased risk of developing diabetic retinopathy complications[19]. Pharmacists should review the patient’s most recent retinopathy screening report prior to initiation, and inform patients of symptoms to look out for and to seek medical attention if any of the following occur:

- Persistent or progressive blurred vision;

- Loss of vision;

- New floaters or black spots in vision[19].

At every appointment, retinal screening attendance should be actively encouraged and reiterated.

Liraglutide should be used with caution if the patient has a history of thyroid cancer or a family history of medullary thyroid cancer as adverse effects, such as goitre, have been reported in trials, particularly in patients with pre-existing thyroid disease[11].

Caution is also advised in the following disease states:

- T2DM with suspected beta-cell failure — consider insulin instead as GLP-1 and GIP analogues require beta cell function to be effective;

- Liver impairment — pharmacists should check individual drug SPC for recommendations. All GLP-1 and GIP analogues require no dose adjustments in hepatic impairment; however, some have limited experience in certain levels of liver impairment and therefore caution in use may need to be exercised;

- Renal impairment — pharmacists should check individual drug SPC for recommendations as dose adjustments may be required and can vary between individual drugs;

- Dehydration — owing to the potential for GLP-1 and GIP analogues to exacerbate dehydration generally associated with nausea, vomiting and/or diarrhoea;

- Hypoglycaemia — patients receiving GLP-1 and GIP analogues therapy alongside sulfonylureas or insulin therapy may have an increased risk of adverse effects[5–11].

Potential class side effects

Side effects can impact the disease burden of people taking GLP-1 and GIP analogues and negatively affect adherence. Pharmacists should be aware of the following side effects to properly advise and help patients manage accordingly:

- Hypoglycaemia — consider dose reduction of concomitant medications, particularly sulfonylurea and insulin, to prevent hypoglycaemia if this a concern;

- Gastrointestinal effects (e.g. nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain) are common across the class — nausea is likely at initiation and decreases over time. Caution should be taken with dehydration and renal function decline. Pharmacists should advise patients on the potential for dehydration and to take precautions to avoid fluid depletion by maintaining adequate fluid intake of sugar-free fluids and, if unwell, following their usual sick day rules (advice for managing the condition during concurrent illness);

- Reduced appetite — delayed gastric emptying and therefore reduced appetite is an expected effect of GLP-1 and GIP analogues;

- Diabetic retinopathy complications — rapid improvement in glucose control has been associated with temporary worsening of diabetic retinopathy. Patients should be advised to report any symptoms of worsening retinopathy immediately, such as persistent or progressive blurred vision, loss of vision, new floaters or black spots in vision;

- Pancreatitis — patients should be counselled on characteristic symptoms (severe abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhoea, fever) and action to take. If the patient develops symptoms, they should be advised to discontinue GLP-1 and GIP analogue treatment and contact their healthcare professional immediately;

- Possible changes to international normalised ratio (INR) in patients on warfarin or coumarin derivatives. The reason for this is unknown, therefore more frequent monitoring is recommended (e.g. at initiation, dose change and cessation);

- Renal function decline — as GLP-1 and GIP agonists can cause nausea, diarrhoea and vomiting, this may result in dehydration and associated reduction in renal function. If renal function does reduce, it may be of value to discuss side effects experienced with the patient and reiterate the importance of maintaining adequate fluid intake when unwell;

- Rapid weight loss — patients should be monitored for signs and symptoms of cholelithiasis, such as biliary colic pain. If this occurs, GLP-1 and GIP therapy should be withheld while this is investigated;

- Injection site reaction — pharmacists should assess the patient’s injection technique and ensure site rotation. Most GLP-1 and GIP therapies come with comprehensive patient information leaflets detailing injection technique information that can be used to support this. Furthermore, some products, such as dulaglutide and semaglutide, also have electronic mobile apps which can be used to prompt dosing and site rotation alongside reiterating overall education;

- Headache — can be managed with simple analgesia and is not a reason to discontinue GLP-1 and GIP therapy;

- Tachycardia — tachycardia should be reviewed by a medical professional in case of other causes and is not a reason to discontinue GLP-1 and GIP therapy;

- Hypersensitivity — drug excipients should be reviewed against the patient’s current allergy status/record to identify any potential causes. Provided symptoms can be managed (e.g. with analgesia, antihistamines) and reactions are not indicative of anaphylaxis, this is not a reason to discontinue therapy; however, changing to an alternative GLP-1 or GIP with a different excipient profile should be considered if hypersensitivity is unmanageable for the patient;

- Small reduction in blood pressure — provided patients are asymptomatic, this is not a reason to discontinue GLP-1 or GIP therapy. Again, patients should be encouraged to maintain adequate fluid intake[5–11,19–21].

It is important to note, as with all drug side effects, that not all people will experience these. Patients should be informed of potential side effects and safety-netted appropriately in case these occur. Care should be individualised if side effects occur, considering impact and potential risks, with ongoing side effects balanced against indication and benefit of GLP-1 and GIP therapy.

Potential notable drug interactions

Possible drug interactions also need to be considered. Notable examples include:

- Beta-blockers — the warning signs of hypoglycaemia (e.g. tremor) may be masked during concurrent treatment with a beta-blocker;

- Paracetamol — lixisenatide possibly reduces the absorption of paracetamol when given one to four hours before paracetamol;

- Warfarin — GLP-1 and GIP analogues possibly enhance the anticoagulant effect of warfarin;

- Other orally administered drugs — may need to be taken at specific times in relation to meals and other medicines to minimise possible interference with absorption. Pharmacists should consult individual SPCs.

- Other antidiabetic drugs — owing to the increased risk of hypoglycaemia, the dose of concomitant sulfonylurea and/or insulin may need to be reduced. Any dose adjustments need to be undertaken on an individualised basis considering individual patient considerations, HbA1c target, hypoglycaemic awareness and medication regimen[5–11].

Summary

This article has highlighted the position of GLP-1 and GIP therapy in the management of T2DM.

Essential points to remember are that GLP-1 and GIP analogues may be beneficial for people with ASCVD and/or obesity, alongside T2DM as this drug class has shown benefit in improving cardiovascular outcomes and reducing weight, both of which we know are intrinsically linked to T2DM.

Pharmacists can play a vital role in providing individualised care for people with diabetes through the consideration, initiation and subsequent titration of GLP-1 and GIP analogues. Pharmacists can discuss with patients the different options in the class, considering both daily and weekly injectable therapies as well as oral semaglutide, ensuring the choice of GLP-1 or GIP analogue is patient-specific and appropriate.

In addition, pharmacists can provide appropriate injection technique counselling or ensure that oral counselling is undertaken at the point of prescribing; provide a review of people on GLP-1 or GIP therapy; and provide education on common side effects and actions to take if these occur.

- Table 1 was updated on 30 June 2022 to amend information given about the number of pre-filled pens required each month and to include brand names and formulary status.

This article has been reviewed and updated by author Claire Davies to ensure it remains relevant, following its original publication in June 2022.

- 1Heise T, Mari A, DeVries JH, et al. Effects of subcutaneous tirzepatide versus placebo or semaglutide on pancreatic islet function and insulin sensitivity in adults with type 2 diabetes: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-arm, phase 1 clinical trial. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2022;10:418–29.

- 2Boyle JG, Livingstone R, Petrie JR. Cardiovascular benefits of GLP-1 agonists in type 2 diabetes: a comparative review. Clinical Science. 2018;132:1699–709.

- 3Toft-Nielsen M-B, Damholt MB, Madsbad S, et al. Determinants of the Impaired Secretion of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2001;86:3717–23.

- 4Reed J, Bain S, Kanamarlapudi V. Recent advances in understanding the role of glucagon-like peptide 1. F1000Res. 2020;9:239.

- 5TRULICITY 4.5mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11930/smpc (accessed June 2022)

- 6Byetta 10 micrograms solution for injection, prefilled pen. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8617/smpc (accessed June 2022)

- 7Bydureon 2 mg prolonged release suspension for injection in pre-filled pen (BCise). Electronic medicines compendium. 2021. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11085/smpc (accessed June 2022)

- 8Lyxumia Treatment Initiation Pack. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2967/smpc (accessed June 2022)

- 9Rybelsus. Electronic medicines compendium. 2020. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11507/smpc (accessed June 2022)

- 10Ozempic 1 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9749/smpc (accessed June 2022)

- 11Victoza 6 mg/ml solution for injection in pre-filled pen. Electronic medicines compendium. 2020. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6585/smpc (accessed June 2022)

- 12Exendin-4: From lizard to laboratory…and beyond. National Institute on Aging. 2012. https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/exendin-4-lizard-laboratory-and-beyond (accessed June 2022)

- 13Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. 2019 update to: Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2019;63:221–8.

- 14Adult obesity and type 2 diabetes. Public Health England. 2014. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/338934/Adult_obesity_and_type_2_diabetes_.pdf (accessed June 2022)

- 15Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28 (accessed June 2022)

- 16BMI: preventing ill health and premature death in black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups . National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph46/resources/bmi-preventing-ill-health-and-premature-death-in-black-asian-and-other-minority-ethnic-groups-pdf-1996361299141 (accessed June 2022)

- 17Overweight and obesity management NICE guideline [NG246]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG246 (accessed February 2025)

- 18GLP-1 receptor agonists: reports of diabetic ketoacidosis when concomitant insulin was rapidly reduced or discontinued. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2019. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/glp-1-receptor-agonists-reports-of-diabetic-ketoacidosis-when-concomitant-insulin-was-rapidly-reduced-or-discontinued (accessed June 2022)

- 19Bain S. GLP-1 receptor agonists and diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes & Primary Care. 2021. https://diabetesonthenet.com/wp-content/uploads/DPC_23-4_103-104.pdf (accessed June 2022)

- 20Trulicity®(dulaglutide). Apple app store. 2022. https://apps.apple.com/gb/app/trulicity-dulaglutide/id979311931 (accessed June 2022)

- 21Ozempic App UK. Apple app store. 2022. https://apps.apple.com/gb/app/ozempic-app-uk/id1456234925 (accessed June 2022)

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Found it a useful resource for use in clinical practice