This content was published in 2007. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

The two most common conditions affecting the anorectal area (the rectum and anal canal) that pharmacists are likely to encounter are haemorrhoids and anal fissures. Many customers with these conditions find talking about their symptoms embarrassing and pharmacists should be prepared to handle consultations sensitively. Use of a consultation room can encourage more open conversation about these conditions.

Haemorrhoids

Haemorrhoidal tissues are cushions of vascular and connective tissue lined with rectalmucosa. They are a normal part of the rectum and anal canal and have a role in maintaining anal continence, protecting from trauma and providing sensory information (eg, enabling differentiation between solid, liquid and gas). Enlargement or displacement of haemorrhoidal tissue gives rise to haemorrhoidal disease, commonly referred to as “haemorrhoids” or “piles”. This condition is thought to affect around half of the UK population at some time in their lives. However, because many never seek medical advice about their symptoms, it is difficult to define accurately the incidence of haemorrhoids. Haemorrhoidal disease is seen in all age groups from the mid-teens onwards, with incidence tending to increase with age, until the seventh decade of life. It is particularly common in pregnancy.

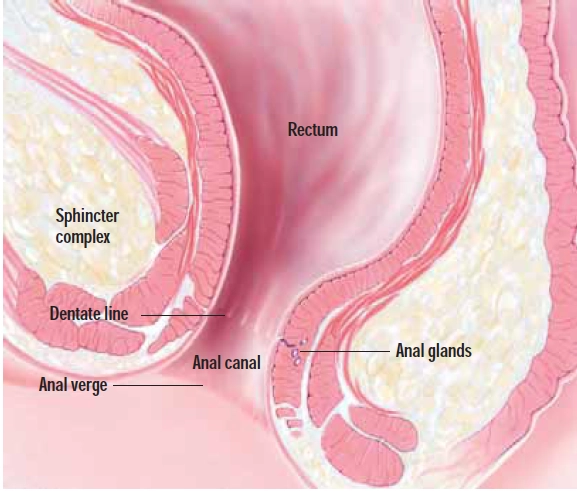

Haemorrhoids are described according to their location. Those originating above the dentate line (see Figure 1 and glossary) are termed internal.

Glossary

Anal verge The opening of the anus on the surface of the body

Dentate line (also called the pectinate line) The junction within the anal canal denoting the transition from anal skin (anoderm) to the lining of the rectum

Posterior midline Aligned withthe midline of the body and going backwards (ie, away from the vagina or scrotum)

Sitz-bath A therapeutic hip bath

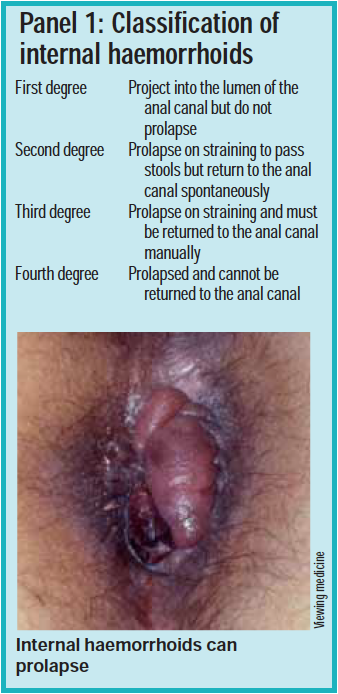

Those arising below the dentate line, under the perianal skin just outside the anal verge, are external haemorrhoids. Internal haemorrhoids are more common and are further classified according to degree of prolapse (see Panel 1).

Pharmacists should ask questions to determine haemorrhoid type because this affects treatment options.

Identify knowledge gaps

- What types of active ingredient are used in preparations for haemorrhoids and what are their actions?

- What is the rationale behind using glyceryltrinitrate to treat an anal fissure?

- What advice can pharmacists give to a person with haemorrhoids or an anal fissure?

Before reading on, think about how this article may help you to do your job better. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s areas of competence for pharmacists are listed in “Plan and record”, (available at: www.rpsgb.org/education). This article relates to “common disease states” (see appendix 4 of “Plan and record”).

Causes

The mechanism that leads to the development of haemorrhoids is uncertain. Predisposing and aggravating factors include:

- Constipation and straining to defecate

- Chronic diarrhoea

- Family history

- Varicose veins (although haemorrhoids are not varicose veins, many people with varicose veins also develop haemorrhoidal disease)

- Pregnancy (pregnancy-related constipation, the increasing pressure of the fetus and peripheral vasodilation all contribute to haemorrhoids)

- Bowel or pelvic tumours

There is no evidence that haemorrhoidsare caused by sitting on cold, hard surfaces.

Although it is unlikely that lifting heavy weights, coughing or standing for long periods cause haemorrhoidal disease, they can worsen symptoms.

Symptoms

Some people ascribe any anorectal symptoms to haemorrhoidal disease and careful questioning is necessary to decide whether to refer or recommend treatment. External haemorrhoids are usually asymptomatic — just a bluish bulging of the blood vessel beneath the skin may be visible. However, if external haemorrhoids become thrombosed they can be acutely painful. The pain can last for up to 10 days. An old, previously thrombosed external haemorrhoid gives rise to a skin tag. Internal haemorrhoids are more likely to cause symptoms, which include:

- Bleeding (fresh blood may be seen on toilet paper, in the toilet following defecation or on the stool surface)

- Anal itching and irritation (due to discharge of mucus)

- Discomfort following defecation

- Mucus associated with stools

- Third or fourth degree haemorrhoids may impair fecal continence (eg, they may prevent the anal sphincter closing properly)

Occasional, additional symptoms arise due to complications of the haemorrhoids. These include:

- Ulceration (following thrombosis of external haemorrhoids)

- Maceration (due to mucus discharge

- Ischaemia, thrombosis or gangrene (especially if internal haemorrhoids remain prolapsed)

- Perianal sepsis (rare)

- Anaemia (due to persistent bleeding)

Customers complaining of haemorrhoidal symptoms for the first time usually require referral to exclude more serious conditions. And anyone with co-existing symptoms of unexplained weight loss, fatigue or altered bowel habit needs to be referred promptly.

Doctors make a diagnosis after medical examination, which may include visualisation of the anus and rectum using a proctoscope.

Management

There are many ointments, creams, gels and suppositories available for symptomatic relief of both internal and external haemorrhoids. Choice of formulation depends on the location of the haemorrhoid and on patient preference. For example, suppositories are indicated for internal haemorrhoids. Some creams come with a nozzle so are appropriate for internal as well as external application.

Common ingredients used in haemorrhoidal preparations include:

- Mild astringents (eg, allantoin, bismuthoxide, hamamelis [witch hazel], zinc oxide

- Emollients (eg, white soft paraffin to easestool passage)

- Mild antiseptics (eg, benzyl benzoate, bismuth oxide, zinc oxide, balsam of Peru [sensitive individuals may have an allergic reaction to constituents of balsam of Peru])

- Local anaesthetics (Preparations containing local anaesthetics [eg, benzocaine, lidocaine] can give relief from irritation and itching and ease stool passage. There can be some absorption through the rectal mucosa and skin sensitisation with continued use, so they should only be used for a few days at a time. Cinchocaine, pramocaine and tetracaine tend to be more irritant.)

- Corticosteroids (Preparations containing corticosteroids [eg, fluocortolone, hydrocortisone, prednisolone] are used for their anti-inflammatory action. They may cause skin atrophy and be absorbed to some extent, so are not for long-term use [up to one week only]. They should be used with caution in pregnancy and avoided in people with local infection.)

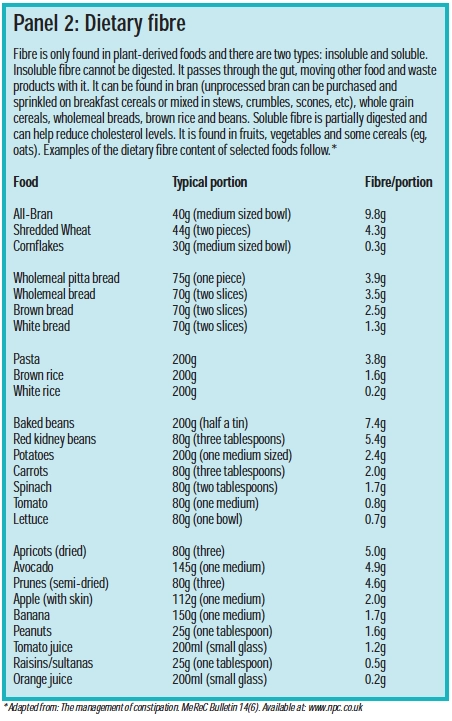

A high-fibre diet alongside increased fluid intake is recommended for all patients with haemorrhoidal disease to soften stools and to reduce or prevent constipation and the need to strain at defecation. Panel 2 lists the approximate dietary fibre content of various foods.

If dietary measures are insufficient to relieve constipation, bulk-laxatives may be recommended or prescribed. Other advice for avoiding constipation includes taking regular exercise and not ignoring the urge to defecate. (Constipation was discussed in a previous CPD article PJ, 7, July, pp23–6). Additional general advice that pharmacists can give to people with haemorrhoids is listed in Panel 3.

A patient with an acutely painful external haemorrhoid should be referred. This indicates thrombosis and, if diagnosed within 72 hours of the onset of pain, most commonly requires surgical excision.

Internal haemorrhoids (usually third or fourth degree) giving rise to unacceptable symptoms (eg, frequent bleeding) require referral to a colorectal surgeon who might use:

- Haemorrhoidectomy (by surgery or stapling)

- Rubber band ligation (a band is applied around the haemorrhoid, cutting off the blood supply and causing it to drop off)

- Sclerotherapy (injection of a hardening or sclerosing agent [eg, oily phenol injection] into the vein, causing it to scar and drop off)

- Infrared coagulation to restrict blood flow to the haemorrhoid, causing it to shrink and drop off

- Cryosurgery

Anal fissures

An anal fissure is a small tear or ulcer of the lining of the anal canal, immediately within the anal verge (see Figure 2).

Most (90 per cent) of these tears occur in the posterior midline, although women may experience tears in the anterior midline, particularly following childbirth.

Anal fissures are a common condition and can affect people of any gender or age, although 87 per cent of cases occur in those between 20 and 60 years. The fissure can be defined as acute or chronic. Acute fissures have been present for less than six weeks and have a sharply demarcated edge. Chronic fissures tend to be deeper and associated with some secondary features, such as hardening of the edges. In multiple fissures the doctor should exclude the possibility of underlying disease, such as inflammatory bowel disease and sexually transmitted disease (eg, anal herpes and gonorrhoea).

Pharmacists should be aware that the term “anal fissure” is commonly confused with“anal fistula”, which is an abnormal connection between the anal canal and the skin surrounding the anus. This is usually the result of an abscess that has not healed properly but issometimes associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Treatment is surgical.

Causes

Various causes of anal fissures have been proposed, including mucosal ischaemia secondary to muscle spasm. About a quarter of cases are the result of the passage of hard stools, causing local trauma. A complicated delivery in childbirth can result in an anterior midline fissure. Anal injury (eg, due to analintercourse, rectal examination and laxative use can also cause fissures). Patients with fissures, particularly chronic ones, often have a raised anal canal pressure due to spasm of the internal anal sphincter muscle.

Symptoms

Although tears are usually small, they can be extremely painful. The pain is described as “sharp and searing” or “burning” and is worse during and after defecation. Pain can continue for up to two hours after defecation. There may be a small amount of bleeding, usually noticed as bright red blood on toilet paper. There may be anal itching due to discharge of mucus from the anal tissue.

Management

The management of an anal fissure depends on whether it is acute orchronic.

Acute anal fissures

Dietary advice (regarding high-fibre and fluid intake) and bulk laxatives where appropriate (or lactulose in children) are sufficient in most cases. The aim is to keep faeces soft while the fissure heals.

Oral paracetamol can give some pain relief (constipating analgesics, such as codeine, should be avoided) and topical anaesthetics are sometimes used in the short-term, but evidence for their effectiveness over placebo is lacking. Topical corticosteroids are sometimes used to reduce inflammation, but are probably of little benefit. Sitz-baths in warm water for up to five minutes, followed by cold water for one minute, can be helpful. Application of a lubricant, such as white soft paraffin, before defecation may give some relief from pain when passing a stool.

Chronic anal fissures

All the advice and symptomatic measures applicable to acute anal fissures apply to chronic fissures. In addition, for adults with chronic anal fissures, glyceryl trinitrate ointment is prescribed toproduce vasodilation. Release of nitric oxide from the GTN also causes relaxation of the anal sphincter and reduced anal pressure and this, along with its vasodilatory effect, promotes healing of the fissure.

A 0.4 per cent GTN ointment is licensed for use in chronic anal fissures. A pea-sized amount of ointment, applied twice a day for up to eight weeks, has been shown to reduce pain but appears to be only marginally better than placebo in promoting healing.1 Patient information leaflets recommend covering the finger with cling film before applying the ointment.

The most common adverse effect of GTN ointment is headache (in 50 per cent of patients), which is dose-related. Headaches usually diminish with time. A 0.2 per cent ointment (unlicensed special) is sometimes prescribed if side effects to the 0.4 per cent are unacceptable.

Contraindications, cautions and drug interactions associated with oral GTN may apply to GTN ointment. As with GTN tablets, the ointment should be discarded eight weeks after opening the tube.

If the fissure has not responded to topical GTN over eight weeks then the patient should be referred to a specialist, who may consider surgery to reduce anal sphincter tone. This is most commonly achieved by a lateral internal sphincterotomy (LIS), in which the anal sphincter is weakened by a small cut. Healing rates are high following a LIS, but the procedure carries a risk of incontinence (mainly to flatus) of around 10 per cent.

Other treatments being investigated include topical calcium channel blockers (diltiazem and nifedipine), which have a similar effect to GTN ointment. Botulinum toxin A has also been used and been shown to reduce spasm when injected into the internal anal sphincter by inhibiting the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction.2

Anal fissures can recur. Risk of recurrence can be decreased by increasing dietary fibre and pharmacists can advise on this. One study shows that patients taking 15g of bran each day had significantly fewer recurrences than those taking 7.5g daily or placebo (16 per cent compared with 60 per cent and 68 per cent, respectively).

References

- UK Medicines information. Glyceryl trinitrate 0.4% ointment. New medicines profile. Available at www.ukmi.nhs.uk (accessed on 11 June 2007).

- Giral A, Memiflo K, Gültekin Y, Imeryüz N, Kalayci C, Ulusoy NB et al. Botulinum toxin injection versus lateral internal sphincterotomy in the treatment of chronic anal fissure: a non-randomized controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterology Available at: www.biomedcentral.com (accessed on 11June 2007).

Resources

- Prodigy guidance on anal fissure. Available at: www.cks.library.nhs.uk (accessed on 11 June 2007).

- Prodigy guidance on haemorrhoids. Available at: www.cks.library.nhs.uk (accessed on 11 June 2007).

Action: practice points

Reading is only one way to undertake CPD and the Society will expect to see various approaches in a pharmacist’s CPD portfolio.

- Formulate what questions you would ask a customer complaining of anal itching.

- Discuss with another pharmacist, which products are the most useful for haemorrhoidal symptoms.

- Make sure you can advise on how GTN ointment should be used (eg, the patient information leaflet and summary of product characteristics for Rectogesic are available at http://emc.medicines.org.uk).

Evaluate

For your work to be presented as CPD, you need to evaluate your reading and any other activities. Answer the following questions: What have you learnt? How has it added value to your practice? (Have you applied this learning or had any feedback?) What will you do now and how will this be achieved?

You might also be interested in…

Two-prescriber sign-off no longer required for isotretinoin

Terence Wheeler (1945–2026)