In 2012, an estimated 35.3 million people in the world were living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Some 69% were living in Sub-Saharan Africa, where nearly 1 in 20 adults is affected[1]

. Public Health England estimated that by the end of 2012 there were 98,400 people living with HIV in the UK, an increase of 2,400 people on the previous year[2]

. The overall prevalence of HIV in 2012 was 1.5 per 1,000 people, with the highest rates reported among men who have sex with men (47 per 1,000) and the black African community (38 per 1,000).

Despite the success of antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV infection rates remain high and implementation of measures to prevent transmission remains a challenge.

Transmission

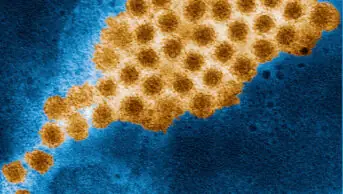

HIV belongs to the family of lentiviruses. It is a retrovirus, meaning that its genetic information is encoded in RNA. The retrovirus genome needs to be reverse-transcribed into DNA by viral reverse-transcriptase before it can replicate.

The virus is present in the blood, semen, pre-seminal fluid, rectal fluids, vaginal fluids and breast milk of infected individuals. These fluids must come into contact with a mucous membrane or damaged tissue, or be directly injected into the bloodstream, for transmission to occur. The main routes of HIV transmission are through sexual contact, sharing injecting equipment with an HIV-infected person, or from an HIV-infected mother to her child (vertical transmission) before or during birth, or through breastfeeding. Risk factors for HIV infection include:

- Having unprotected vaginal or anal sex

- Having another sexually transmitted infection (STI) such as syphilis, herpes, chlamydia or gonorrhoea. Genital ulcers can cause breaks in the genital tract lining or skin. These breaks create a portal of entry for HIV. Additionally, local inflammation increases the concentration of cells in genital secretions that can serve as targets for HIV (eg, CD4+ lymphocytes). STIs also appear to increase the risk of an HIV-infected person transmitting the virus to his or her sexual partners

- Sharing contaminated injecting equipment

- Receiving contaminated blood transfusions or undergoing medical procedures that involve unsterile cutting or piercing

- Experiencing a needle stick injury

- Being born to an HIV-infected mother

Infection

When a person is infected with HIV, the virus goes through multiple stages to replicate (see Figure, right). Although it can infect numerous cells, its main targets are lymphocytes that express the protein CD4 (referred to as CD4+ cells).

Clinical features

After infection, an acute syndrome associated with primary HIV infection is observed in some individuals. This syndrome is mainly characterised by lymphadenopathy, fever, maculopapular rash and myalgia, and can last for several weeks. Because of the non-specific nature of these symptoms, diagnosis is often missed at this stage.

The concentration of HIV RNA in blood is very high during the primary infection phase, and the risk of onward transmission of the virus is particularly high. The virus destroys CD4+ cells in the replication process and CD4+ cell count can fall rapidly after infection. The destruction of CD4+ cells impairs cell-mediated immunity — increasing the risk of opportunistic infection and some cancers. Eventually, the host immune response will begin to bring the viral RNA levels down to less than 1% of the maximum value at the time of seroconversion. This remains at a relatively stable level for several years. This level is called the viral set point and is different for each patient.

A chronic, asymptomatic phase of HIV disease then follows. During this clinical latency stage, HIV-infected individuals exhibit little or no symptoms of disease. The baseline CD4+ cell count in HIV-infected individuals will decline from a normal value of around 1,000 cells/ml at varying rates. There is a great deal of individual variability in this progression, with some individuals progressing rapidly and others retaining near-normal counts. Signs and symptoms suggestive of HIV during this period of declining immune function include lymphadenopathy, oral candidiasis, herpes zoster infection, diarrhoea, fatigue, fever and blood dyscrasias, such as leukopenia, anaemia and thrombocytopenia.

Without ART, a patient’s CD4+ cell count can drop to below 200 cells/ml and a succession of AIDS-defining illnesses can develop. These include infection with Mycobacterium avium complex, Pneumocystis jiroveci, Cryptococcus neoformans, Toxoplasma gondii, cytomegalovirus and other opportunistic pathogens. HIV infection should be suspected when common infections (eg, herpes zoster, herpes simplex and candida) are severe or recurrent.

Some patients develop cancers, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma and B-cell lymphomas, which occur more frequently, are unusually severe or have unique features in those with HIV infection. For some patients, neurological dysfunction and HIV-associated nephropathy may occur.

Simplified diagram of the HIV replication cycle

Diagnosis

HIV tests work through antigen-antibody binding. HIV antibody production (seroconversion) begins around two weeks after infection and, in most cases, antibodies can be detected after around four to six weeks. The p24 antigen, a core protein in the HIV virus, is detectable before the first occurrence of HIV-specific antibodies. Testing for HIV immediately after a possible transmission will not detect HIV antibodies.

Fourth-generation tests, which can detect p24 antigen and HIV-specific antibodies, have narrowed the diagnostic gap to two to four weeks. Fourth-generation tests also require a small venous blood sample (50μl). Third-generation tests are less sensitive, but some can test saliva samples — offering a convenient alternative to blood sampling. HIV infection cannot be excluded until at least three months after possible transmission and a negative test result is only reliable if repeated exposure has not occurred since the original exposure.

In 2012, an estimated one in five HIV-positive people were unaware of their HIV status in the UK. In the same year, 6,360 new HIV diagnoses were made, of which 47% were late diagnoses (CD4+ cell count <350 cells/ml).2 Early diagnosis of HIV infection is important for preventing progression to AIDS. Joint guidelines produced by the British HIV Association (BHIVA) and the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) recommend that an HIV test should be offered routinely to all patients who attend certain services (eg, antenatal services), develop HIV indicator conditions (see Box 1) or report a history of high-risk behaviour[3]

. Other recommendations for testing are described in Box 2.

| Box 1: Clinical indicator diseases for adult HIV | ||

Disease area | HIV testing should be offered | AIDS-defining conditions |

Respiratory | Bacterial pneumonia Aspergillosis | Tuberculosis Pneumocystis pneumonia |

Neurological | Aseptic meningitis/encephalitis Cerebral abscess Space occupying lesion of unknown cause Guillain-Barré syndrome Transverse myelitis Peripheral neuropathy Dementia Leukoencephalopathy | Cerebral toxoplasmosis Primary cerebral lymphoma Cryptococcal meningitis Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy |

Skin | Severe or recalcitrant seborrhoeic dermatitis Severe or recalcitrant psoriasis Multidermatomal or recurrent herpes zoster infection | Kaposi’s sarcoma |

Gastrointestinal | Oral candidiasis Oral hairy leukoplakia Chronic diarrhoea of unknown cause Weight loss of unknown cause Salmonella, shigella or campylobacter infection Hepatitis B infection Hepatitis C infection | Persistent cryptosporidiosis |

Malignant | Anal cancer or anal intraepithelial dysplasia Lung cancer Seminoma Head and neck cancer Hodgkin’s lymphoma Castleman’s disease | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

Gynaecological | Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (histology grade 2 or above) | Cervical cancer |

Blood | Any unexplained blood dyscrasia, including thrombocytopenia, neutropenia and lymphopenia | None applicable |

Eye | Infective retinal diseases including herpes viruses and toxoplasma Any unexplained retinopathy | Cytomegalovirus retinitis |

Ear, nose and throat | Lymphadenopathy of unknown cause Chronic parotitis Lymphoepithelial parotid cysts | None applicable |

Other | Mononucleosis-like syndrome (primary HIV infection) Pyrexia of unknown origin Any lymphadenopathy of unknown cause Any sexually transmitted infection | None applicable |

Broadening access to HIV testing and reducing time from infection to diagnosis are crucial to reducing HIV incidence. Testing for HIV and other STIs is strongly advised for all people exposed to any of the risk factors.

Changes in legislation came into effect on 6 April 2014 to allow the sale HIV home-testing kits in the UK. Community pharmacies are now able to offer patients the option of taking an HIV test and obtaining a result without the need to send the sample elsewhere. This change in legislation offers community pharmacists a new opportunity to provide regulated, quality-assured tests to more people.

This service needs to be accompanied by a robust care pathway and seamless referral system to ensure patients with a reactive result have access to a confirmatory antibody test and specialist care within an appropriate timeframe (less than 48 hours). Pharmacists offering HIV tests will need to be familiar with the pathway for referring patients to GUM and HIV services.

The World Health Organization recommends that HIV testing should be voluntary and any person’s right to decline testing should be respected. Mandatory or coerced testing undermines good public health practice and infringes on human rights. All testing and counselling services should include the “five Cs” as recommended by the WHO. These are:

- Informed consent

- Confidentiality

- Counselling

- Correct test results

- Links to care, treatment and other services

Box 2: Recommendations for HIV testing3

Universal testing is recommended for all people who access the following services:

- Genitourinary medicine and sexual health clinics

- Antenatal services

- Termination of pregnancy services

- Drug dependency programmes

- Healthcare services for those diagnosed with tuberculosis, hepatitis B and C and lymphoma

Consider testing the following groups in areas where diagnosed HIV prevalence in the local population exceeds 2 in 1,000 population:

- All men and women registering with a GP

- All general medical admissions

Routinely offer and recommend HIV testing to:

- Patients for whom HIV, including primary HIV infection, has been a possible differential diagnosis

- Patients diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection

- Sexual partners of men and women known to be HIV positive

- Men who have disclosed sexual contact with other men

- Female sexual contacts of men who have sex with men

- Patients reporting a history of injecting drug use

- Men and women known to be from a country of high HIV prevalence (>1%)

- Men and women who report sexual contact abroad or in the UK with individuals from countries of high HIV prevalence

In line with Department of Health guidance, HIV testing should be routinely performed in the following groups:

- Blood donors

- Dialysis patients

- Organ transplant donors and recipients

Prevention

HIV transmission can be prevented. Pharmacists can help to increase awareness of HIV prevention among patients and other healthcare professionals. There is currently no effective vaccine for the prevention of HIV infection. However, studies are ongoing. The main strategies for prevention of HIV transmission are outlined below.

Condoms Condoms should be used correctly and consistently. The use of male and female condoms during vaginal or anal penetration can protect against the spread of sexually transmitted infections. Community pharmacists are ideally placed to encourage use of condoms.

Treatment as prevention Data from several studies of serodiscordant couples (ie, one partner is HIV-positive and the other is HIV-negative) have demonstrated that when an HIV-positive partner adheres to ART, the risk of transmitting the virus to his or her uninfected sexual partner is substantially reduced. This is known as treatment as prevention (commonly referred to as TasP).

International guidelines on the indications for antiretroviral therapy and when it should be started differ (see accompanying article, p145). BHIVA recommends that conversations with patients who are newly diagnosed should include explaining that adherence to treatment with ART can lower the risk of onward transmission. A person’s risk of transmitting the virus to others should be assessed as part of these discussions[4]

.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis Clinical trials in serodiscordant couples have demonstrated that antiretroviral medicines taken by HIV-negative partners can prevent HIV transmission. This is known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). This practice is not currently funded in the UK and further investigation is needed to determine its value.

Post-exposure prophylaxis Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) involves the administration of antiretroviral medicines within 72 hours of exposure to HIV to prevent infection. PEP is often given to health professionals following occupational exposure to needles and potentially infectious fluids at work. It can also be used after sexual exposure to the virus. PEP is available from GUM clinics and most accident and emergency departments. The standard course of PEP is a 28-day course of antiretrovirals.

Safe injecting practice Injecting drug users can minimise risk of infection by taking appropriate precautions such as using sterile injecting equipment for each injection. Interventions that pharmacists can help to implement, or signpost patients to, include:

- Offering needle exchange services

- Providing opioid substitution therapy

- Offering HIV testing and counselling

- Providing HIV treatment and care

- Improving access to condoms

Mother-to-child transmission All pregnant women should be tested for HIV routinely. Most maternity services in the UK have an “opt-out” system for HIV testing of pregnant women. This increases the number of expectant mothers who are tested and helps to make routine testing more acceptable to service users.

Recommendations for prevention of mother-to-child transmission include providing ART to mothers and infants during pregnancy, labour and the post-natal period. BHIVA has produced guidelines for the management of HIV infection in pregnant women[5]

.

References

[1]World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS factsheet 360. October 2013.

[2]Public Health England. HIV in the United Kingdom: 2013 report. November 2013.

You might also be interested in…

Everything you need to know about mpox

Norovirus and strategies for infection control