This content was published in 2013. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

As the financial envelope in which the acute sector of the NHS is expected to operate continues to shrink, innovative ways of streamlining pharmacy services are needed[1]. The likely scenario for the future is that pharmacists will have less time to see a greater number of patients, and these patients will likely be sicker, have more complex needs and be taking more medicines. Clinical pharmacists will need to be able to focus their efforts on the patients who need them most.

At the Countess of Chester Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, the patient administration system (Meditech) is integrated such that electronic prescribing (e-prescribing), laboratory data, nursing care notes, pharmacy care notes and patient demographics are incorporated into the same system. As our experience with recently implemented e-prescribing matures, we are reviewing the practices of clinical pharmacists to maximise opportunities around integration of e-prescribing and the electronic patient record. Here we describe some of the ways technology is assisting pharmacy teams to deliver pharmaceutical care to inpatients.

Pharmacy care plans

Electronic pharmacy care plans (PCPs) have been designed locally and are available to other healthcare professionals who may wish to view them. Within the plan, the pharmacist or technician reviewing a patient can record medication history, adherence issues and any particular problems identified on screening, and set out and prioritise any issues that require follow-up. Drug allergies and the nature of reactions are included within the e-prescribing module and other data, eg, past medical history, can be automatically pulled into the PCP from medical clerking notes, avoiding duplication of work.

Medicines reconciliation

Pharmacists are able to record findings of the initial medicines reconciliation on admission — including medicines taken before admission, the source of information, any discrepancies identified and adherence issues (eg, use of compliance aids). Future care plans are automatically populated with important information, which can be edited if necessary at future admissions. When the pharmacist records that the patient has had his or her medicines reconciled, the time and date of this are logged and used to calculate and record whether patients have had their medicines reconciled within the target time; this information is collated as part of the pharmacy key performance indicators (KPIs) on medicines reconciliation [2].

The medicines history recorded by the pharmacist is also visible via the electronic prescription screen throughout the patient’s stay, making it easier to identify changes to a patient’s medicines when preparing a discharge prescription and accompanying discharge letter. When pharmacists screen patients’ prescriptions and verify their content as appropriate, they mark each item as “reviewed”. This allows the e-prescribing system to report for a specific ward or consultant team the prescriptions that have not been reviewed and pharmacists are able to prioritise these. Clinical managers can use the system to ensure that pharmacists are checking patients’ prescriptions and recording these checks for governance purposes (eg, for NHS Litigation Authority evidence).

Follow-up and prioritisation

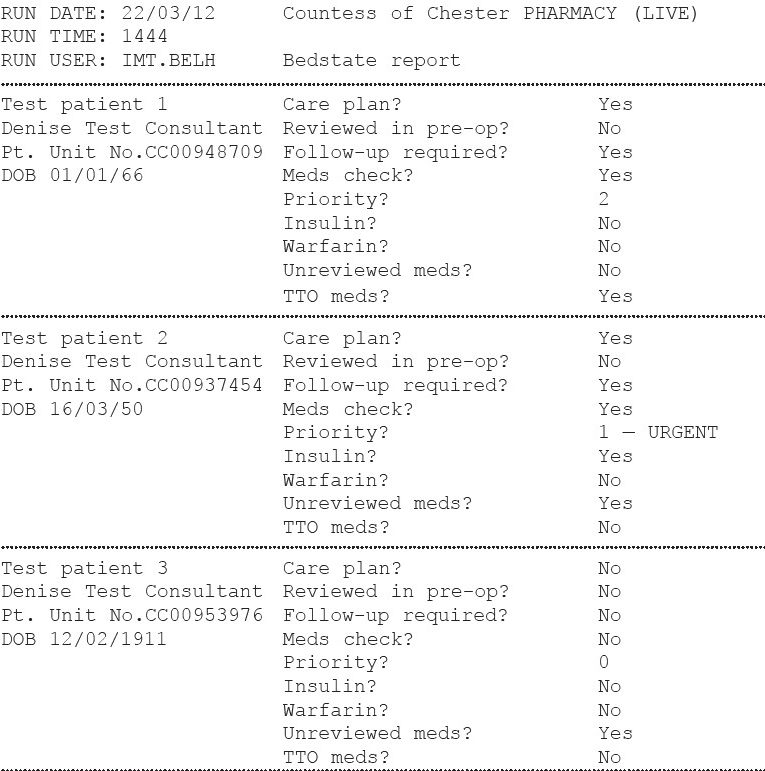

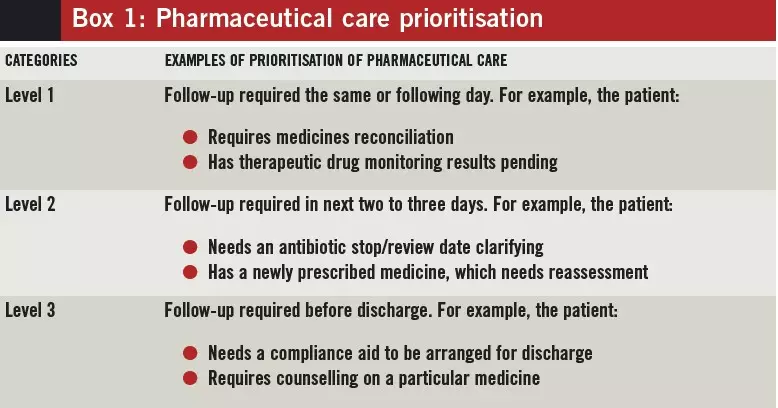

Pharmacists are able to assign a level of priority for follow-up so that patients can be targeted for review at the next ward visit, or by a pharmacist on another ward if the patient moves. A review of a ward patient list can simply identify those who should be prioritised for follow-up. Examples of clinical situations and associated level of priority are described in Box 1. To enable pharmacists to plan their ward visits efficiently, a report has been developed which provides information showing which patients are in the greatest need of attention (known as a bedstate report). The examples in Figure 1 are described below:

- Test patient 1 has TTO (discharge prescription) medicines, which prompts the pharmacist to make the necessary preparation to facilitate the patient’s discharge. The patient is also tagged as requiring a level 2 follow-up, indicating that a medicine needs to be reviewed before discharge

- Test patient 2 has a “Priority 1 — urgent” follow-up; further detail on the reason for this will be found in the PCP and he or she also has unreviewed medicines. The pharmacist can prioritise the patient and access his or her electronic prescription either remotely or at the bedside to identify any changes or to confirm whether actions from the previous assessment have been completed

- Test patient 3 has been flagged as not having had medicines reconciliation (“Meds check? No”), and has yet to be seen by a pharmacist, indicating a high priority.

Antibiotic stewardship

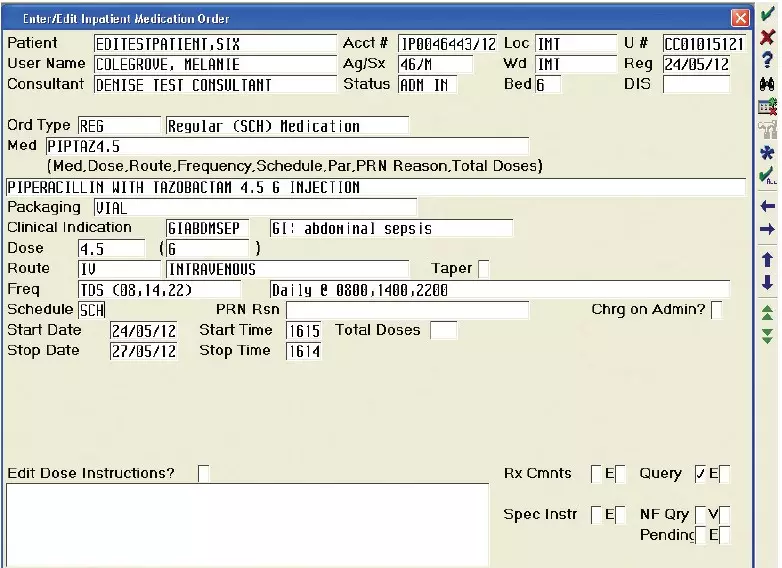

To support antibiotic stewardship, the system requires an indication for antibiotic prescriptions as a mandatory field (see Figure 2), which can be audited against the trust formulary. Junior medical staff are required to document that they have discussed the need for antibiotics with a named senior clinician. The system has default automatic stop dates (three days for intravenous antibiotics; five days for oral), which can be a problematic if prescribers accept the defaults without due consideration.

Therefore we have built a reminder into the system, which the prescriber has to acknowledge before entering the prescription. The system can also identify which patients are prescribed antibiotics, for how long and scheduled stop dates. It can identify those taking restricted antibiotics to facilitate antimicrobial ward rounds. The e-prescribing system also offers efficiencies around the reporting of antibiotic prescriptions across the trust for audit purposes.

Drug supply endorsements

A key role for pharmacy remains the timely supply of medicines to patients and, previously, staff were alerted to the supply of medicines by endorsements on medication charts that were often illegible and poorly understood by nursing staff, and became outdated when patients moved to new wards. The e-prescribing system allows pharmacy staff to endorse when and where supplies have been made for individual prescription items. This function also allows other endorsements to be made (eg, if there is a supply problem) and these can be added remotely from the pharmacy department.

Missed doses

In accordance with the National Patient Safety Agency alert regarding missed doses,[3] pharmacy staff can run a routine report to identify patients who have missed doses of their medicines, allowing them to take appropriate action. This function is also useful when conducting audits because it allows for rapid data collection from the system.

Recording interventions

Pharmacists’ clinical contributions or interventions are recorded as part of the patient record and logged against patient episodes directly from the prescription. Pharmacists’ contributions can be grouped into number, category, severity or British National Formulary class for departmental KPI reports and for review in educational meetings for clinical pharmacists.

Discharge prescriptions

Like with most e-prescribing systems, the electronic discharge prescription used at the Countess of Chester Hospital is relatively simple to generate and is emailed to the patient’s GP automatically. Pharmacists can make notes on the prescription that are included in the discharge correspondence for the GP’s attention. Details about special requirements, such as the use of compliance aids, are printed on the prescription to ensure dispensing staff are aware of each patient’s needs.

On-call

Pharmacists who are on call can access the system from home or elsewhere; therefore, should a query about a particular patient arise the pharmacist can view the relevant medicines, blood test results and care notes.

In summary

The use of e-prescribing and local design of the PCP have allowed pharmacists to document their activity in an accessible format and use this to direct the focus of their efforts. The e-prescribing system also has a number of applications that support audit, data collection for KPIs and workload review. As the technology around electronic patient records and e-prescribing develops, the opportunities to use this system will grow. It is essential that there is a strategy for the integration of different systems that feed into a single patient record, which can be used wherever the patient is cared for.

References

1 Department of Health. Making the NHS more efficient and less bureaucratic. March 2013. www.dh.gov.uk/health/category/policyareas/ nhs/quality/qipp/ (accessed 8 August 2012).

2 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and National Patient Safety Agency. Technical patient safety solutions for medicines reconciliation on admission of adults to hospital. December 2007. www.nice.org.uk (accessed 8 August 2012).

3 National Patient Safety Agency. Reducing harm from omitted and delayed medicines in hospital. February 2010. www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/alerts (accessed 8 August 2012).