This content was published in 2007. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Constipation is a common complaint, with incidence estimated at 12–19 per cent.1 Constipation means different things to different populations, individual patients and health care professionals, so it can be difficult to define. One broad definition of constipation is the passage of hard stools less frequently than is normal. Many misconceptions surround bowel habits and what is normal, leading to misdiagnoses and overuse of laxatives. “Normal” can be anything from passing stools two or three times a day to two or three times a week. It is a change from the norm for the individual that is significant.

Cause

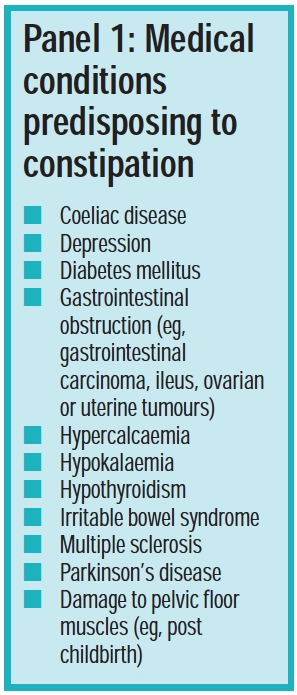

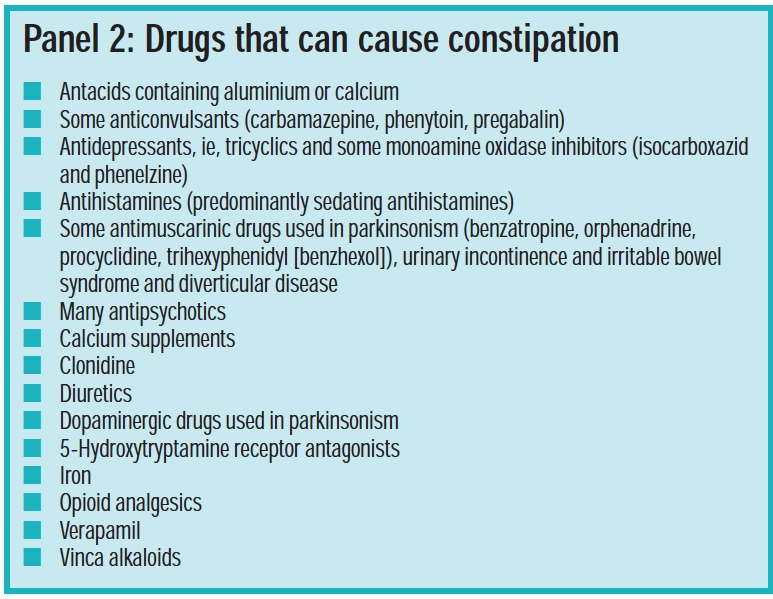

Constipation can be classed as primary (idiopathic) or secondary (induced by a specific condition [see Panel 1] or medicine [see Panel 2]). In most cases there is no pathological cause.

Many non-medical factors predispose to constipation. The most significant are:

- Inadequate fluid intake (the normal stool consists of about 70 per cent water and dehydration results in a hard stool that can be difficult to pass; dehydration can be exacerbated by drugs, such as diuretics)

- Inadequate dietary fibre (the average UK adult consumes 12g fibre daily — far less than the 18g recommended by the Department of Health)

- Dieting (eg, slimming diets can be low in fibre)

- Changes in lifestyle (eg, eating different foods or at different times, reduced physical activity)

- Suppressing the urge to defecate

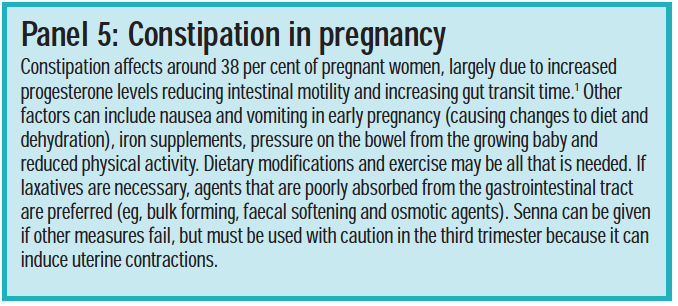

Constipation is frequently experienced by pregnant women and older people (particularly those in institutions). Increased incidence in older people is multifactorial and reasons include side effects of medicines, reduced mobility, reduced intake of fibre-rich food (eg, due to dental problems) and medical conditions. Constipation is an often overlooked aspect of patient care in acute settings and can become a significant problem if it does not receive necessary attention.

Identify knowledge gaps

- Which drugs predispose to constipation as a side effect?

- What affects choice of laxative?

- What advice can be given to parents with constipated children?

Before reading on, think about how this article may help you to do your job better. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s areas of competence for pharmacists are listed in “Plan and record”, (available at: www.rpsgb.org/education). This article relates to “common disease states” (see appendix 4 of “Plan and record”).

Symptoms

Common symptoms of constipation are difficulty passing stools, abdominal discomfort and abdominal distension. If untreated, constipation can lead to:

- Faecal impaction (when a large mass of faeces cannot be passed) and bowel obstruction (with potential to progress to bowel perforation)

- Faecal and urinary incontinence

- Urinary tract infection

- Rectal bleeding

- Anal fissures

Straining to defecate can cause haemorrhoids, fainting and cardiac irregularities. It can worsen gastro-oesophageal reflux and mobilise a deep vein thrombus.

Diagnosis

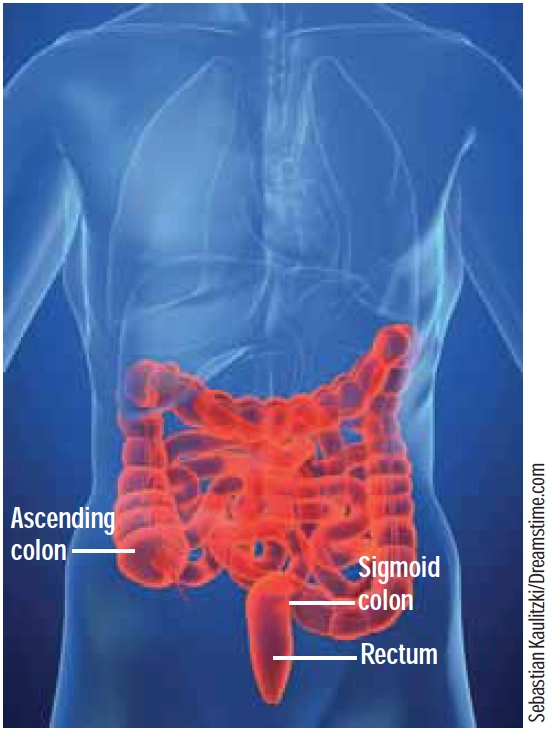

The key feature in diagnosing constipation is a change in bowel habit from the norm for the individual. Constipation can result from lodged faeces in any part of the large bowel, but this usually occurs in the sigmoid colon or rectum (see Figure 1).

For chronic constipation, the Rome II diagnostic criteria for functional gastroduodenal disorders is sometimes used for diagnosis. It considers bowel habits over three months and includes such parameters as straining at defecation; lumpy, hard stools; sensations of tenesmus (a continuous feeling of needing to defecate) or blockage; fewer than three bowel movements weekly and the use of manual techniques (eg, digital evacuation) to facilitate defecation.

Patients describing constipation as a new symptom unattributable to changes in lifestyle, medication or diet, should be referred. Any of the following symptoms should also trigger referral:

- Constipation alternating with diarrhoea

- The presence of blood or slime, or both, with or in the stools

- Constipation accompanied by abdominal pain or vomiting

- Unintentional weight loss

- Tenesmus

Chronic constipation has been linked to an increased risk of colon and rectal cancer. However, a transient period of harder stools or reduced frequency of defecation is a low risk symptom for colorectal cancer.

Treatment

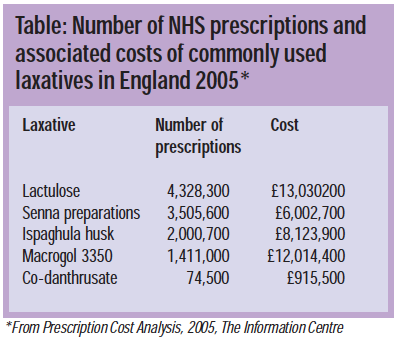

In 2005, a quarter of the prescriptions for gastrointestinal medicines in England were for laxatives, costing over £50m. (The Table gives an idea of the laxatives most commonly prescribed and the relative costs.)

However, many constipation remedies are available over the counter. The aims of treatment are to:

- Restore normal frequency of defecation

- Achieve regular, comfortable defecation using the least number of drugs for the shortest time

- Avoid laxative dependence

- Relieve discomfort2

In general, all patients benefit from dietary and lifestyle advice. A minimum of 18g and up to 30g fibre and 2L of fluid daily is recommended for adults.3 However, it should be noted that fluid increase is contraindicated in some people (eg, in heart or renal failure). Most people see benefits in three to five days, but it can take a month for a new fibre-rich diet to take full effect. Increased exercise is beneficial in constipation. Patients should also be encouraged to respond immediately to any urge to defecate. Failure to do so can result in a build-up of faeces that continue to have water absorbed from them, making them more difficult to pass.

Laxatives are used when dietary measures are not feasible, when they have failed or while waiting for dietary measures to take effect. They are also useful in situations where straining to pass stools should be avoided (eg, angina, haemorrhoids), and in drug-induced constipation.

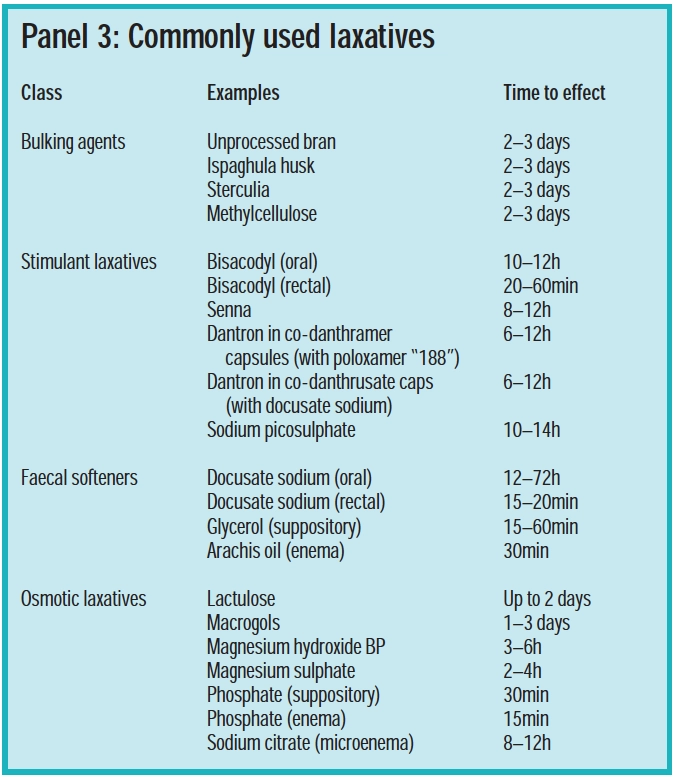

There are four main groups of laxatives: bulk-forming, stimulant, osmotic and faecal-softening. There is limited evidence comparing the effectiveness of laxatives, so drug selection should be based on:

- Patient preference

- How quickly an effect is needed (see Panel 3)

- Whether the stool is hard or soft

- Side effects

- Cost

Where constipation is not induced by necessary drug therapy or chronic illness, the laxative should be used for a short time until dietary and lifestyle changes become effective.

Bulk-forming laxatives

Bulk-forming laxatives (ispaghula husk, sterculia and methylcellulose, which is also a faecal softener) add mass to faeces to stimulate peristalsis. They are particularly useful if stools are small and hard. They take several days for full effect so are not suitable for immediate relief but can be used by patients with normal gut motility and uncomplicated constipation. They are also used long-term in patients whoare prone to constipation. Proprietary ispaghula or sterculia granules should be mixed with water and taken immediately, Celevac (methylcellulose) is a tablet formulation. It is important to maintain good fluid intake with all bulk-forming laxatives to avoid intestinal obstruction.

Bulk-forming laxatives should not betaken just before going to bed. They commonly cause increased flatulence and abdominal bloating in the early stages of treatment, but these settle with time.

Stimulant laxatives

Stimulant laxatives increase intestinal motility by direct stimulation of colonic nerves; they do not act on the small intestine (bisacodyl is an exception). Members of this group include senna (ananthranoid derived from plants), dantron (asynthetic anthranoid associated with bowel and liver tumours in animals and restricted to use in patients who are terminally ill), bisacodyl and sodium picosulfate (polyphenolics which are hydrolysed to the same active metabolite). Senna and bisacodyl are most commonly used short-term for acute constipation. They should be avoided where there is obstruction. Taken before going to bed, they produce a bowel movement the following morning. They can cause abdominal cramps and prolonged use should be avoided because they can cause diarrhoea and fluid and electrolyte imbalance. Bisacodyl suppositories can cause local inflammation and dantron can colour urine red.

Faecal softeners

Docusate sodium has some stimulant activity but is chiefly a faecal softener, lowering surface tension and allowing water to penetrate hard, dry faeces. It is combined with dantron in co-danthrusate foropioid-induced constipation in palliative care.

Glycerol suppositories and arachis oil enema can be used rectally to soften impacted faeces. Arachis oil should not be used by people who are allergic to nuts. Liquid paraffin is no longer recommended.

Osmotic laxatives

Osmotic laxatives work within the colonic lumen to retain and draw water into the intestine by osmosis. Lactulose, macrogols, magnesium salts, phosphates and sodium salts fall into this group.

Lactulose is a semi-synthetic disaccharide(galactose and fructose combined). It is not absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, so it can be used by people with diabetes. It takes two to three days to take effect so will not give immediate relief. Side effects are flatulence and abdominal discomfort.

Macrogol powders (polymers of ethyleneglycol) have shown some benefits over lactulose in small, short-term trials. They can be more effective in increasing stool frequency and reducing straining over four weeks and may be less likely to cause flatulence. However, macrogol powders may be more likely to produce liquid stools. By nature of their action, osmotic laxatives need to be accompanied by good fluid intake.

Magnesium hydroxide is purgative and can be abused, but occasional use is acceptable. Magnesium sulphate is sometimes used when rapid bowel evacuation is needed. Again this is not suitable for regular use.

Suppositories and enemas

Suppositories and enemas can be used when oral laxatives are ineffective or there is impaction low down in the gastrointestinal tract.

Choice of product depends on the site of impaction and the type of stools. Relatively soft rectal faeces respond to bisacodyl suppositories provided there are no haemorrhoids or anal fissures. Hard rectal stools may be treated with glycerol suppositories which are hygroscopic, lubricant, and have some stimulant activity.

For more severe impaction a softening enema, such as docusate sodium or arachis oil, can be used overnight followed by a phosphate enema (osmotic laxative) the following morning. Enemas are not intended for regular use, but may need to be repeated several times to clear impacted faeces.

Basic tips that pharmacists can give for enema use include:

- Warm the enema to body temperature (eg, using a jug of warm water)

- Lubricate the nozzle with lubricating jelly or white soft paraffin to ease insertion

- Use a towel to lie on

- The patient should lie on his or her side, with knees drawn up

- The tube length selected (long or short) depends on patient (or carer) preference for ease of use and does not affect nozzle positioning in the rectum

- Holding the enema above the upper hip can aid administration

- After administration, sphincter muscles should be squeezed for a few minutes to stop the liquid running out

Herbal laxatives

Plant extract laxatives are either bulk-forming (eg, psyllium, linseed, fenugreek) or stimulant (eg, senna leaves, cascara bark, aloe latex, buckthorn, alder buckthorn and rhubarb). Evidence comparing herbal agents with conventional laxatives is lacking, and the British National Formulary recommends herbal laxatives are avoided because their action is unpredictable. They are, however, sold in some pharmacies and may be requested by customers. Cautions for use apply as with conventional preparations.

Special considerations

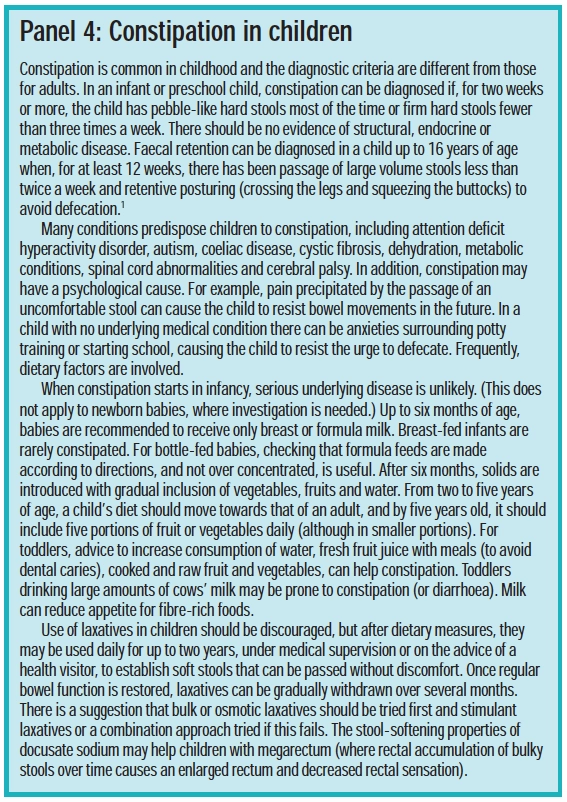

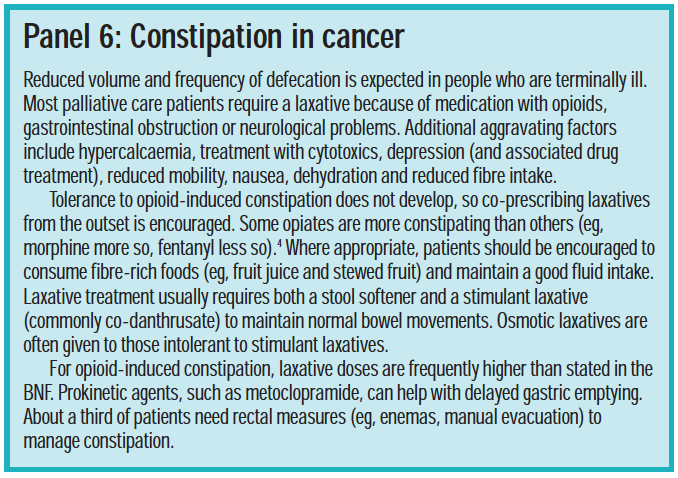

As mentioned, some people (eg, pregnant women and the terminally ill) are more prone to constipation. In addition, constipation in children requires special consideration. These groups are discussed in Panels 4, 5 and 6.

Laxative misuse and eating disorders

Laxatives are listed as potential substances of misuse in the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s practice guidelines. Misuse can occur in those with eating disorders, such as anorexia, but also in normal or overweight individuals. Laxative misuse in the UK has been reported at 2 per cent in secondary school students and 13 per cent in college students. Pharmacists need to be aware and ready to advise those buying laxatives repeatedly and excessively, and direct customers to support agencies.

References

- Prodigy guidance on the management of constipation. Available at: www.cks.library.nhs.uk (Accessed on 25 May 2007).

- The management of constipation. MeReC Bulletin 14(6). Available at: www.npc.co.uk (Accessed on 25 May 2007).

- National Prescribing Centre. Management of constipation. Prescribing Nurse Bulletin. Available at: www.npc.co.uk. (Accessed on 17 May 2007).

- Constipation and the use of laxatives: a comparison between transdermal fentanyl and oral morphine. Available at: http://intl-pmj.sagepub.com (Accessed on 17 May 2007).

Resources

- www.dh.gov.uk contains information on constipation and the risk factors for cancer

- www.eatwell.gov.uk contains information on healthy eating

- www.radcliffe-oxford.com/books/samplechapter/5111/01_PCF2-398cb9c0rdz.pdf contains information on constipation in palliative care

Action: practice points

Reading is only one way to undertake CPD and the Society will expect to see various approaches in a pharmacist’s CPD portfolio.

- Discuss with your staff five basic questions to ask a person complaining of constipation.

- How would you deal with a teenager buying laxatives frequently? Discuss with a colleague.

- Read the section on laxatives in the BNF for Children. Which laxatives can be used in children under two years old?

Evaluate

For your work to be presented as CPD, you need to evaluate your reading and any other activities. Answer the following questions: What have you learnt? How has it added value to your practice? (Have you applied this learning or had any feedback?) What will you do now and how will this be achieved?

You might also be interested in…

The engagement imperative

Why Ramadan is a clinical opportunity for pharmacy