Jim Gibson / Alamy Stock Photo

The number of services delivered through community pharmacy is increasing, as community pharmacy staff take on extended roles such as managing long-term conditions, flu vaccinations, sexual health services and more. Evaluation is an essential part of improving the quality of healthcare and understanding whether the services being provided are delivering what they set out to deliver[1]

. There is currently limited high quality published evidence that recognises the role of community pharmacies in delivering extended roles and clinical services in the community[2]

,[3],[4]

. This is not dissimilar to the lack of evidence for other primary care services, which can make it difficult to justify investment in certain services. While randomised controlled trials demonstrating improved clinical outcomes would be the ideal, a pragmatic approach using quality improvement processes and methodology to implement services and test them in practice can help support decision making[5]

,[6]

. Increasing the robust evaluation of implemented services enables commissioners to understand where community pharmacies can be used to deliver relevant services at the heart of local communities. As well as patient outcomes, there is an increasing focus on patients’ involvement and experience of their healthcare, which can influence decision making[7]

,[8]

. This article aims to support pharmacists and healthcare professionals in conducting a service-based evaluation within community pharmacy.

What is evaluation?

Evaluation has various definitions, all of which identify that this process aims ‘to determine value or worth’[6],[8],[9],[10]

. The purpose of evaluation is often to:

- Determine whether desired change has been achieved;

- Identify whether things have improved as a result of the service implementation or intervention;

- Determine opinion of a service from its users;

- Determine whether a service is cost effective;

- Justify further investment;

- Allow others to learn from the sharing of knowledge.

The evaluation must be designed to address any questions that stakeholders may want answered[6],[11],[12]

. This will mean using different methods of evaluation depending on the design of the service[6],[11],[12]

. Clear aims and objectives will help guide the evaluators about which approach is most appropriate and the best methods to choose (See ‘Box 1: The difference between aims and objectives, using a stop smoking service as an example’)[12]

. For a community pharmacy, a service evaluation increases the evidence base that demonstrates its ability to deliver services that improve patient outcomes and are cost effective for the NHS.

Box 1: The difference between aims and objectives, using a stop smoking service as an example

Aims are generalised statements about the overall purpose of the evaluation.

- To evaluate the effectiveness of a new stop smoking service in a community pharmacy.

Objectives are specific, realistic outcomes that the evaluation aims to measure within the time and resources available.

- Determine staff and patient opinion of the stop smoking service;

- Measure the extent to which clinical outcomes have been achieved (e.g. the number of patients who have stopped smoking);

- Identify the costs involved in delivering the stop smoking service (e.g. increased opportunity cost of the staff member delivering a stop-smoking service rather than a different pharmacy service).

Who should conduct the evaluation?

It is important to consider whether the service’s evaluation is undertaken by staff members (internal evaluation) or non-staff members (external evaluation)[13],[14]

. This may depend on the evaluation’s intended audience and the level of credibility required[13]

. Internal evaluation may be cheaper and could be conducted in a timely manner because staff may be more readily available. Internal staff also often have an advantage because they have knowledge of the service and the context in which it was established. Therefore, internal evaluation may be relevant when it is needed quickly to be considered within an annual commissioning cycle or where privately delivered services are being evaluated and no external funding or publication is desired.

By contrast, external evaluators may bring specialist skills in evaluating, have greater objectivity and may encourage participants to be more open, giving an external evaluation more credibility[6],[13]

. Therefore, external evaluation is more applicable where greater credibility is needed to commission on a larger scale or where publication of findings to influence future service delivery is required. However, this does not mean that internal evaluations are not worthy of publication or that they do not add to the evidence base.

Approach to evaluation

Evaluation often uses similar activities to research; both are systematic and share similar steps. It is their purpose that divides them; research seeks generalisable results in a controlled setting to address a knowledge gap whereas evaluation judges the merit or worth of a specific service to aid decision-making[15]

. The Health Foundation suggest a ‘balanced scorecard’ approach that takes into account patient experience, the cost of the service, the process and the patient outcomes (see ‘Figure 1: Balanced scorecard approach to evaluation’)[6]

.

Outcome evaluation (summative evaluation) looks at the overall effectiveness or impact of a service (e.g. whether the patient’s asthma is better controlled as a result of the intervention)[6],[14]

. Process evaluation (formative evaluation) looks at the methods or process through which the service is delivered and may focus around quality standards of the delivery (e.g. whether the consultation included inhaler technique counselling[6],[14]

). Good evaluation uses a mixture of these approaches and combines qualitative and quantitative methods to provide a well-rounded evaluation that triangulates data (i.e. views the results from more than one perspective and gives a better picture of the overall service)[6],[11],[12],[14]

. This is important because the service outcomes may be good but the patients or staff may not like the service or may find it impractical to deliver[6],[14]

. When deciding on the approach to evaluation, it is useful to determine whether anyone has evaluated the same type of service previously to review their approach and data collection tools used.

Figure 1: Balanced scorecard approach to evaluation

Source: The Health Foundation. Measuring patient experience. London 2013

A mixture of process, clinical outcome, patient experience and resource measures within the evaluation gives an improved overall picture of the service.

Determining the effectiveness of your service

If a service has clear measures in place, these can be compared elsewhere or to the previous status quo

[6],[14]

.

Before and after comparisons measure baseline data before the service is implemented, then after to compare the two sets of results.

Comparison with external/national benchmarks uses routinely collected data that are compared with the service data. There are various places where national data can be gained including the Office of National Statistics (ONS) and NHS Digital (formerly Health and Social Care Information Centre [HSCIC])[16]

,[17]

.

Control group comparison compares the outcomes of those using the service with the outcomes of a group of people not using the service who have similar demographics (e.g. a group of people in an area where the service may not exist).

Collecting data for evaluation and record keeping

It is essential to think about the evaluation when the service is being designed to guarantee baseline data are collected in advance and to determine when the evaluation is likely to take place (see ‘Box 2: When to conduct the evaluation’). A well-designed service will consider evaluation from the outset and build in data collection, feedback and measurement of outcomes to the service delivery[6]

. It is important to identify whether the data needed will be captured as part of the service delivery and you can draw on existing data sets or whether further data collection is required at the point of evaluation. Data collection should not be onerous on those delivering the service and should be acceptable to participants to facilitate completion of full data sets. Data collection usually includes:

- Patient demographics;

- Clinical outcome including proxy measures;

- Where the intervention took place;

- Length of time;

- Cost.

Box 2: When to conduct the evaluation

There is no specific timeframe that dictates when the evaluation must be conducted. The timing should consider whether:

- The results need to feed into a business planning cycle to obtain ongoing funding;

- Sufficient activity has taken place to be able to draw conclusions from the data (e.g. have there been sufficient patient numbers seen within the service);

- The evaluation should be conducted at the end of the service or during, taking into account that doing it at the end may mean a break in funding and service while the outcomes are assessed. Over the life of a service there may be a number of developmental phases, each of which should be evaluated.

Clear aims and objectives help identify which data may need gathering during service delivery. For example, if the evaluation has an objective to determine the cost-effectiveness of an intervention, data must be captured during the service delivery, which enables costs to be calculated (e.g. time taken to deliver service or the medicines supplied). This may be data that are already captured to facilitate claims for a service. For example, for minor ailments services, data on number, type and cost of medicines provided are required to be able to calculate the average cost per patient of a visit to the pharmacy. Data that do not meet the aims of the evaluation should not be collected.

Measuring patient experience

There is an increasing drive within the NHS to gather patient feedback routinely[7],[8]

. Historically, patient experience and satisfaction were gathered through questionnaires and interviews, although more recently there has been an increased focus on patient stories as a strategy for improvement and other methods of eliciting patient experience[6],[18],[19]

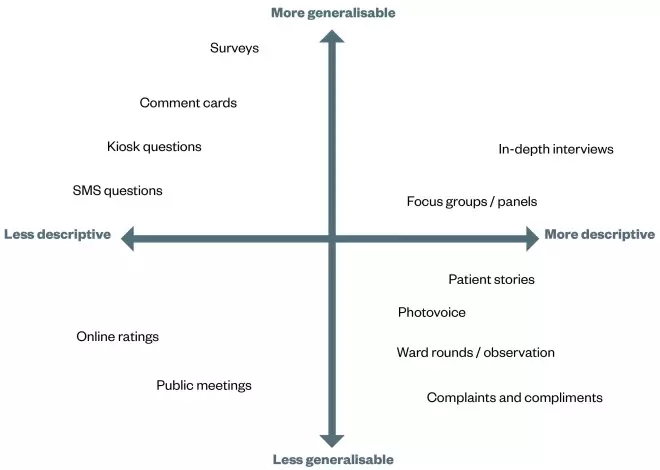

. The depth and extent to which these are representative of the population varies depending on the method (see ‘Figure 2: Examples of methods used to measure patient and carer experience of healthcare’)[8]

. Those methods that provide more in-depth information can often be more time consuming and may not be as generalisable[8],[18],[19]

. The method chosen should be one that meets the aims and objectives of the evaluation and can be conducted with the timeframes established. For example, where there are short timescales and a large number of responses are required to determine whether patients generally liked a service, a questionnaire may be more appropriate. In comparison, if there are longer timescales and more detail is required to understand how a service might be developed further or what the barriers are to delivering a service within community pharmacy, interviews may provide more in-depth answers.

Figure 2: Examples of methods used to measure patient and carer experience of healthcare

Source: The Health Foundation. Measuring patient experience. London 2013

Main approaches that have been used to measure patient experience. Approaches are categorised according to the depth of information they provide and the extent to which they collect information that may be generalisable to a wider population. In selecting an appropriate approach, it may be necessary to weigh up the importance of depth versus generalisability, or to combine approaches to gain a mixture of both.

Patient feedback that contains both quantitative and qualitative data is useful because it gives the evaluator an idea of scale and rationale. Wording of the questions is important to gain appropriate responses and ensure that participants understand the question, interpret it appropriately and are not offended[18]

.

The method of delivering the questionnaire and the collation of responses can often be difficult in community pharmacy because patient data (e.g. the address and telephone number of the patient) may not be captured during service delivery. This means that questionnaires cannot be subsequently posted to patients or patients cannot be contacted via phone or text message to ask for their feedback. Therefore, it is important to:

- Consider whether to ask everyone using the services or only a sample to provide feedback;

- Consider when the best time to collect feedback is (e.g. immediately after using the services, when experiences are fresh in people’s minds);

- Ensure that patients, carers, managers and healthcare professionals are all comfortable with why feedback is being collected and how it will be used;

- Consider how the end-result needs to be presented for various audiences because this may shape how data are collected.

Analysing and presenting data

The content of the evaluation should be aimed toward your audience and the outcome you want as a result of publishing your findings (e.g. ongoing funding from the commissioner). This does not have to be in a report; it could be in a presentation or an infographic. There may be some instances where statistical calculations are needed to measure significant improvement following the intervention being measured but, in many cases, simple presentation of frequencies and graphs are as beneficial, measuring against a baseline where possible. Finally, there is consensus that any research findings and evaluation should be available in the public domain, irrespective of whether the findings are positive or negative.

Additional resources

Top tips for evaluating services

- Be clear about what is being evaluated;

- Engage stakeholders;

- Understand the resources available for evaluation;

- Design the evaluation to address the questions that you would like answering;

- Develop an evaluation plan when designing the service;

- Consider whether a baseline data collection is needed before the start of the new service or practice change so that the change can be measured;

- Decide when the best time is to conduct the evaluation;

- Collect, process, analyse and interpret results;

- Provide recommendations and impact on practice;

- Disseminate findings.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Parry GJ, Carson-Stevens A, Luff DF et al. Recommendations for evaluation of health care improvement initiatives. Acad Pediatr 2013;13(6):S23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.04.007

[2] Brown TJ, Todd A, O’Malley CL et al. Community pharmacy-delivered interventions for public health priorities: a systematic review of interventions for alcohol reduction, smoking cessation and weight management, including meta-analysis for smoking cessation. BMJ Open 2016;6(2):e009828. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009828

[3] Newton J. Consolidating and developing the evidence base and research for community pharmacy’s contribution to public health: a progress report from Task Group 3 of the Pharmacy and Public Health Forum. Public Health England. 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/271682/20140110-Community_pharmacy_contribution_to_public_health.pdf (accessed August 2016)

[4] Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC). The value of community pharmacy – detailed report PSNC. Available at: http://psnc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/The-value-of-community-pharmacy-detailed-report.pdf (accessed September 2016)

[5] Simpson S. Evidence to support development of pharmacy services: how much or how little do we need? Can J Hosp Pharm 2010;63(2). doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v63i2.886

[6] Health Foundation. Evaluation: what to consider. London 2015. Available at: http://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/EvaluationWhatToConsider.pdf (accessed July 2016)

[7] Richards T, Coulter A & Wicks P. Time to deliver patient centred care. BMJ 2015;10:350. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h530

[8] The Health Foundation. Measuring patient experience. London 2013. Available at: http://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/MeasuringPatientExperience.pdf (accessed July 2016)

[9] Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2016. Available at: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/ (accessed September 2016)

[10] Cambridge English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. 2016. Available at: http://dictionary.cambridge.org/ (accessed September 2016)

[11] Denscombe M. The good research guide: for small-scale social research projects. London: Open University Press, 2003.

[12] Smith F. Conducting your pharmacy practice research project. London: Pharmaceutical Press, 2006.

[13] Conley-Tyler M. A fundamental choice: internal or external evaluation? Evaluation Journal of Australasia 2005;4:3–11.

[14] Fox M, Martin P & Green G. Doing practitioner research. London: Sage, 2007.

[15] Twycross A & Shorten A. Service evaluation, audit and research: what is the difference? Evid Based Nurs 2014;17:65–66. doi: 10.1136/eb-2014-101871

[16] Office for National Statistics. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/ (accessed August 2016)

[17] NHS Digital. Available at: http://digital.nhs.uk/ (accessed August 2016)

[18] McColl E, Jacoby A, Thomas L et al. Design and use of questionnaires: a review of best practice applicable to surveys of health service staff and patients. Health Technology Assessment 2001;5(31). doi: 10.3310/hta5310

[19] Murphy E, Dingwall R, Greatbatch D et al. Qualitative research methods in health technology assessment: a review of the literature. Health Technology Assessment 1999;2:16. doi: 10.3310/hta2160