This content was published in 2008. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Interpreting blood glucose results and being able to adjust insulin doses are useful skills for pharmacists to possess.

The key to acquiring these skills is in understanding:

- The insulin regimen and the onset, peak and duration of action for the insulins used;

- The glucose levels to aim for;

- How to titrate insulin doses;

- How all of the above relates to patients’ lifestyles and eating habit.

Understanding the regimen

Insulin may be given alone or, for those with type 2 diabetes, with oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs), often metformin. Although this article focuses on adjusting insulin doses, readers should bear in mind that oral doses may also need to be adjusted. The three most commonly used insulin regimens are:

- Once daily intermediate-acting or long-acting insulin — normally given at bedtime or during the day, usually withan OAD;

- Twice-daily pre-mixed insulin — one injection before breakfast, one before the evening meal (pre-mixed insulins contain fixed ratios of short- and long-acting insulins);

- Basal-bolus insulin — three daily injections of rapid- or short-acting insulin with meals and one or two injections of intermediate- or long-acting (basal) insulin.

The onset, peak and duration profiles of insulin products available in the UK can be found with this article on PJ Online. These should be used when interpreting a blood glucose result, to determine which insulin was exerting its effect at the time of glucose measurement.

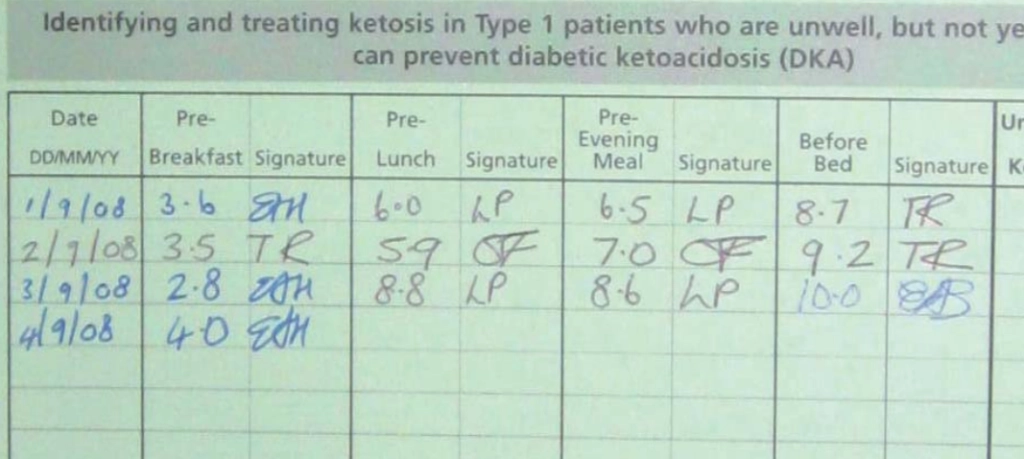

Glucose targets

Glucose levels are usually recorded one to four times a day, depending on the stability of a patient’s condition. If carried out four times daily, glucose levels are usually measured before meals and at bedtime.

The following levels are commonly recommended:

- Before breakfast (fasting level):5.5–6.0mmol/L (with no nocturnal hypoglycaemia);

- Before lunch and before evening meal:4.0–6.0mmol/L;

- Before bed: 6.0–8.0mmol/L If postprandial (after eating) insulin levels are being monitored, they should be taken two hours after each meal and aim to be less than 8.0mmol/L.

Some patients may be set different targets (eg, those elderly patients who are prone to hypoglycaemia).

Altering the dose correctly

When reviewing a blood glucose chart, pharmacists should make a note of any levels that consistently fall outside the recommended target. One-off deviations can be ignored, although hypoglycaemia will usually need to be treated with glucose or glucagon.

Provided other causes can be excluded (other causes include infection, which may raise glucose levels, or the consumption of large amounts of alcohol, which may lower levels a few hours later), practitioners should determine which insulin dose is responsible for persistently aberrant glucose levels.

This requires the onset, peak and duration of action for each insulin that the patient is prescribed to be considered. For example, if a patient is prescribed a twice-daily pre-mixed regimen, the morning dose of insulin is responsible for the patient’s pre-lunch and pre-evening meal glucose levels — the short-acting insulin affects the pre-lunch level and the longer-acting insulin affects the pre-evening meal level. The appropriate insulin dose should then be altered accordingly (see below).

Once adjusted, the glucose monitoring chart needs to be reviewed over the following few days to ensure that the adjustment has altered the glucose levels appropriately.

Adjusting insulin doses

Insulin doses should be titrated slowly. A one-off, high glucose level is not likely to be problematic, however hypoglycaemia can be frightening for a patient to experience and may progress to a coma. Care in avoiding hypoglycaemia is the priority.

In most cases the following recommendations for adjusting insulin doses should be appropriate:

- Short- and rapid-acting insulin — adjust by no more than two units (or 10 percent of the current dose) daily

- Intermediate-acting, long-acting and pre-mixed insulin — adjust by no more than two units, or 10 per cent (whichever is greater), every three to four days

If a patient is prescribed more than one type of insulin, adjust one type at a time. If patients are not in hospital while their insulin doses are being stabilised, practitioners may opt to telephone them at home and make recommendations based on glucose readings taken at home.

However, many patients can be taught to self-manage, so should be encouraged to do so whenever possible. Some tips on avoiding common mistakes when dealing with diabetic patients are described in Panel 1.

Panel 1: Avoiding common mistakes

Do not adjust the insulin dose that follows a deviant glucose level — this will not correct the problem and is likely to cause the next glucose level to be outside the recommended range, creating a cycle of deviant

results.

The original deviant level will have been caused by the previous insulin dose, so this dose will need to be adjusted the following day.

- Do not omit the following dose of insulin if a low glucose level is

recorded. This is not wise, especially in patients with type 1 diabetes who do not produce their own insulin; therefore will be a risk of diabetic ketoacidosis, which is potentially fatal. Doses may be reduced, but should not be omitted; - If there is a known reason for high glucose levels (eg, infection) that

requires an insulin dose to be increased temporarily, do not forget to lower the dose again once the problem is resolved; - While in hospital, many patients do not consume their normal diet. This should be considered when making adjustments to the insulin regimen for inpatients since, if they go home and eat differently, their glucose levels may alter;

- If patients have unusual blood glucose readings while in hospital,

check their usual insulin injection sites. If a different site is used when in hospital to when at home, the absorption of insulin may alter slightly. Furthermore, if a patient injects insulin into exactly the same place every time, lipohypertrophy may occur, which creates a fatty deposit below the skin. If insulin is injected directly into this deposit, drug absorption can be erratic.

Individual treatment

The above recommendations are guidelines — each patient’s individual circumstances should be considered. Also, local policies and guidelines may differ slightly from these recommendations, so it is important to checkthese before adjusting insulin doses.

Elizabeth Hackett is principal pharmacist for diabetes at University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust