Shutterstock.com

Drinking alcohol is a common, widely acceptable activity that people undertake alone or socially; however, a vast number of people are unaware of, or may downplay, the associated risks[1],[2]

. In 2014, more than 10 million people in England were drinking more alcohol per week than is recommended by the UK chief medical officers, increasing their potential risk of serious health problems (e.g. liver disease, depression, cardiovascular conditions and certain cancers)[3],[4]

,[5],. Alcohol use is the leading risk factor for premature death, ill-health and disability among people aged 15–49 years in the UK and globally, and resulted in 7,551 premature deaths in the UK from alcohol-specific causes in 2018, affecting those from more deprived areas to the greatest extent[6]

,[7],[8]

.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were anecdotal reports of people rushing to supermarkets to purchase alcohol, which resulted in a sharp rise in sales. A survey of 2,010 adults in the UK, conducted between 7–9 April 2020 and commissioned by Alcohol Change UK, found that around one in five adults (21%) have been drinking more frequently since the lockdown began[9]

. In addition, although almost half of respondents reported drinking about the same amount on a typical drinking day, 15% reported drinking more per session since lockdown began.

The health risks associated with alcohol consumption begin with any level of regular drinking and rise with the amount of alcohol consumed. At a population level, the most harm is experienced by the larger combined number of low- and moderate-risk drinkers[10],[11]

. Much of this harm is preventable; however, the misuse of alcohol is often under-identified by healthcare professionals, resulting in missed opportunities to provide effective interventions[12]

.

By increasing the awareness of low- and high-risk drinking behaviours and their potential health impacts, and providing advice and support to patients during health conversations, pharmacists and pharmacy teams can empower patients to make informed choices about their alcohol intake.

UK guidance on alcohol consumption

Guidelines published in 2016 by the then Department of Health provide updated recommendations in three main areas:

- Weekly regular drinking;

- Single-occasion drinking; and

- Drinking during pregnancy[3]

.

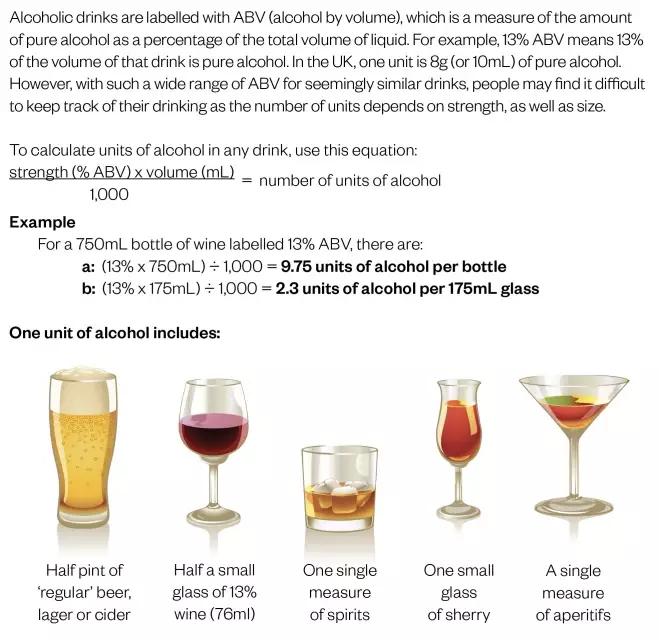

The recommendations refer to units of alcohol and are based on average risks (see Figure 1). Therefore, other factors, such as age, concurrent medicines and current physical or mental health, may also increase an individual’s risk from drinking[3]

.

With such a wide range of alcohol levels by volume for seemingly similar drinks, people may find it difficult to keep track of their drinking — the number of units depends on strength, as well as size. Online unit calculators are available, for example via the Drinkaware and Alcohol Change websites, which aim to help people understand their drinking behaviour and the associated health risks. Further advice on low-risk drinking can be found in the Box.

Box: Guidance on low-risk drinking

Weekly and single occasion drinking episodes

The health risks associated with alcohol start from any level of regular drinking and rise with the increasing amount of alcohol consumed.

Immediate risks from single occasion drinking episodes are related to accident or injury and may involve losing self-control or misjudgement of risk. Risks of injury to an individual have been found to increase by two to five times when 5–7 units are consumed in a 3–6 hour period; however, current guidance does not state specific limits[3]

.

To keep the health risks associated with alcohol consumption low, men and women should be advised:

- That it is safest to drink no more than 14 units per week on a regular basis;

- If they are regularly drinking up to 14 units per week, this should be spread evenly over three or more days;

- That the single occasion drinking guidance will also apply, as one or two heavy drinking episodes per week increases risk of death from accidents or injuries, as well as the risk of long-term illness. This includes:

- Limiting the amount of alcohol consumed on any one occasion;

- Drinking slowly and with food, and alternating alcohol with water or soft drinks;

- Planning ahead for safety (e.g. how to get home)[3]

.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Alcohol can have a range of harmful impacts on a foetus, collectively known as foetal alcohol spectrum disorder.

Women who are pregnant or think they could become pregnant should be advised that:

- The safest approach is not to drink alcohol at all;

- The more alcohol the mother drinks, the greater the risks to the baby;

- The risks of harm are likely to be low from drinking small amounts of alcohol before pregnancy is known[3]

.

As alcohol can pass from the mother into breastmilk, it is safest for women who are breastfeeding not to drink alcohol. If they do drink, they should avoid drinking 2–3 hours before breastfeeding, or they should express milk beforehand to give to their baby later[13]

.

Identifying risks

With limited time during consultations, discussions about alcohol may be of secondary consideration, despite the potential health benefits and inclusion in services, for example the medicines use review. However, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends building alcohol screening into routine practice[5]

. Pharmacists should ask about alcohol consumption at any relevant opportunity (e.g. patients presenting for sexual health advice, or with hypertension, minor injuries or sleep disturbance) even when a modifiable risk factor (e.g. obesity or smoking) was not the original reason for the patient’s visit.

Pharmacists and their teams should be able to undertake alcohol identification and brief advice (IBA) — a short, evidence-based, structured conversation about alcohol consumption, which follows identification of how much the patient is drinking and problems they may be experiencing.

IBA has been included in the UK alcohol prevention strategy since 2012[14]

. A recently updated Cochrane review found that IBA can reduce alcohol consumption in hazardous and harmful drinkers when compared with minimal or no intervention[15]

. However, evidence of its use in community pharmacy settings is limited[16],[17],[18]

.

The conversation involves the steps: identify then advise or refer. The aim is to identify individuals who are not seeking treatment for alcohol problems, but whose drinking behaviour places them at increased or higher risk[5]

. Pharmacists and their teams should open these conversations by asking permission to talk about alcohol consumption, for example “Do you mind if we spend a few minutes talking about healthy lifestyle measures?”, and then following up with questions from the available screening tests[19],[20]

.

Motivational interviewing techniques may also help guide these conversations, as with consultations for smoking cessation or medicines adherence[5]

. It is important to ensure that all conversations are sensitive to people’s culture and faith. Further information and free online training on IBA for community pharmacy is available from Public Health England[21]

.

Screening tests

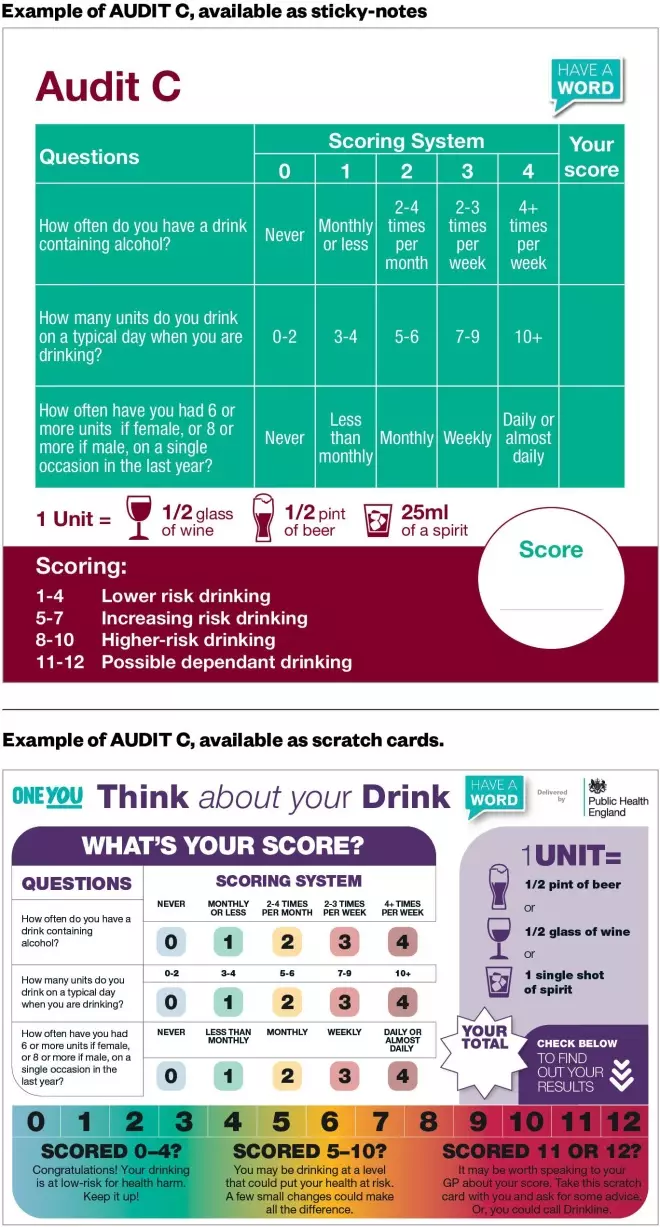

Several evidence-based alcohol screening tests are available, including the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) and alcohol use disorders identification test consumption (AUDIT C)

[22]

. AUDIT includes ten questions to help assess an individual’s level of alcohol risk and is the most widely used instrument for alcohol screening in a primary care setting[23]

. The shorter AUDIT C test comprises the first three AUDIT questions — establishing consumption behaviour — with the score from each question added together to estimate the overall health risk (see Figure 2).

Images of typical units are available as scratch cards or sticky-note versions of AUDIT C, so pharmacists and healthcare professionals can encourage patients to self-complete the tests (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Examples of AUDIT C, available as sticky-notes or scratch cards

Source: eLearning for Healthcare[34]

Visual resources (e.g. NHS One You) or electronic apps/interactive tools that calculate the patient’s weekly drinking in units (e.g. Drinkaware or Alcohol Change UK) can also be used by pharmacists and pharmacy teams during these conversations.

Advising patients

Once a patient’s risk level has been identified, it is important to offer feedback to help them understand how their drinking may be affecting them and contributing to their broader health and wellbeing[5],[24]

. Pharmacists and healthcare professionals should use a patient’s AUDIT C score and suitable guidelines to offer appropriate structured brief advice, as outlined below[5]

.

Raise awareness

For patients scoring 1–4 (lower-risk drinking) on AUDIT C, positively reinforce the concept of units, maintaining low-risk consumption and the risks of increased regular or episodic drinking. As drinking any amount of alcohol regularly increases health risk, do not use the term ‘safe’ when describing drinking behaviours[4]

. Adopt the term ‘low-risk’ drinking to reinforce this message[3]

. If the score is 5 or more (increased risk drinking and beyond), and, if time permits, complete the remaining questions for a full AUDIT.

Potential alcohol dependence is beyond the scope of this article. If a screen or score identifies a high-risk patient or someone who may be alcohol-dependent, they should be made aware of the dangers of stopping drinking alcohol suddenly and encouraged to seek specialist treatment, or to see their GP, depending on local availability[5]

.

Individuals may be unaware of the risks associated with their drinking, such as that acute risks of alcohol consumption include accidental injuries that require hospital treatment (e.g. head and facial injuries, alcohol poisoning) and higher-risk sexual activity, as well as violent behaviour or being the victim of violence[3]

. Long-term risks include cardiovascular conditions, depression, pancreatitis, liver disease and certain cancers[5],[20],[25]

. Awareness of the relationship between alcohol consumption and the increased risks of developing cancers of the mouth and throat, voice box, gullet, large bowel, liver, breast cancer in women and cancer of the pancreas is often poor[1],[26]

.

As well as risk, discuss the possible benefits of reducing alcohol consumption and share information on the hidden calories in alcohol (e.g. a pint of 5% strength beer has the same number of calories as a standard-size Mars Bar)[27]

. Examples of other related benefits include saving money, feeling more energetic, improved sleep or mood, and improved relationships, work or home life.

Provide encouragement

Conversations should be person-centred and tailored to the patient’s individual needs[5]

. Health behaviour theory identifies provision of information as just one aspect of behaviour change[28],[29],[30]

. Aim to facilitate the patient’s decision-making with a non-judgemental, encouraging, empathetic and authoritative approach to improve the likelihood of their choosing to acknowledge and plan to reduce the risks associated with their drinking behaviour[24]

.

Support change

Pharmacists and their teams should discuss practical advice on how patients can reduce their risk, for example:

- Having several alcohol-free days every week;

- Having a smaller-sized drink (e.g. a bottle of beer instead of a pint);

- Having a lower-strength drink (e.g. low-alcohol wine);

- Alternating alcoholic drinks with water or low-sugar soft drinks;

- Avoiding drinking in rounds;

- At home, using a smaller glass and only drinking alcohol at mealtimes;

- Before starting to drink, setting a limit of how much to drink and sticking to it[3]

.

Verbal advice should be supported with written advice or electronic resources, being mindful of health literacy. For example, patients should be signposted to trusted websites, such as NHS Live Well or One You. Patients could be encouraged to use a drinking diary or app to help them identify patterns of drinking, implement drink-free days and reduce the number of units they consume[31],[32]

.

Local, national or contractual campaigns or initiatives can help boost enthusiasm and innovation for a focus on alcohol awareness; for example, Dry January, Alcohol Awareness Week in November and Sober Spring (an initiative from Alcohol Change UK, which runs from March to June). Some cancer awareness campaigns may also be linked to alcohol, as well as smoking.

Referring patients

The primary intent of IBA is not to identify alcohol dependence. However, if screening identifies high-risk patients or those who are alcohol-dependent, pharmacists and healthcare professionals should advise them on how to get help or, with their consent, be referred to specialist services or their GP[5]

. It can be dangerous for people who are severely dependent on alcohol to stop drinking suddenly without appropriate support, particularly if they have physical withdrawal symptoms (e.g. sweating, hand tremors and anxiety)[12],[25]

. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome can lead to seizures, delirium and death in the absence of medical management.

For patients who are concerned about their drinking or someone else’s drinking, or people who have been affected by others’ drinking, there are a range of charities and groups that can help (see ‘Useful resources’).

Useful resources

- Drinkline

- National alcohol helpline (tel: 0300 123 1110; weekdays 9:00 to 20:00, weekends 11:00 to 16:00);

- Action on Addiction

- Alcoholics Anonymous

- Al-Anon Family Groups

- Adfam

- The National Association for Children of Alcoholics (NACOA)

- Pharmacist Support

- Local alcohol addiction services

References

[1] Buykx P, Li J, Gavens L et al. Public awareness of the link between alcohol and cancer in England in 2015: a population-based survey. BMC Public Health 2016;16:1194. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3855-6

[2] Rosenberg G, Bauld L, Hooper L et al. New national alcohol guidelines in the UK: public awareness, understanding and behavioural intentions. J Public Health 2018;40(3):549–556. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdx126

[3] Department of Health. UK chief medical officers’ low risk drinking guidelines. 2016. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545937/UK_CMOs__report.pdf (accessed June 2020)

[4] Wood A, Captoge S, Butterworth A et al. Risk thresholds for alcohol consumption: combined analysis of individual-participant data for 599 912 current drinkers in 83 prospective studies. Lancet 2018;391:1513–1523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30134-X

[5] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Alcohol-use disorders: prevention. Public health guideline [PH24]. 2010. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph24 (accessed June 2020)

[6] Griswold M, Fullman N, Hawley C et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018;392(10152):1015–1035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2

[7] Public Health England. Local alcohol profiles for England. 2019. Available at: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/local-alcohol-profiles (accessed June 2020)

[8] Office for National Statistics. Alcohol-specific deaths in the UK: registered in 2018. 2018. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/bulletins/alcoholrelateddeathsintheunitedkingdom/2018 (accessed June 2020)

[9] Alcohol Change. Drinking during lockdown: headline findings. 2020. Available at: https://alcoholchange.org.uk/blog/2020/covid19-drinking-during-lockdown-headline-findings (accessed June 2020)

[10] O’Dwyer C, Mongan D, Millar S et al. Drinking patterns and the distribution of alcohol-related harms in Ireland: evidence for the prevention paradox. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1323. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7666-4

[11] World Health Organization. Public health problems caused by harmful use of alcohol. 2005. Available at: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/activities/public_health_alcohol/en/ (accessed June 2020)

[12] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking (high-risk drinking) and alcohol dependence. Clinical guideline [CG115]. 2011. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg115/chapter/Introduction (accessed June 2020)

[13] NHS UK. Start 4 Life. Alcohol and breastfeeding. 2016. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/start4life/baby/breastfeeding/healthy-diet/alcohol-and-breastfeeding/ (accessed June 2020)

[14] HM Government. The government’s alcohol strategy. 2012. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/224075/alcohol-strategy.pdf (accessed June 2020)

[15] Kaner E, Beyer F, Muirhead C et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;2(2):CD004148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub4

[16] Dhital R, Norman I, Whittlesea C et al. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions delivered by community pharmacists: randomized controlled trial. Addiction 2015;110(10):1586–1594. doi: 10.1111/add.12994

[17] Hall N, Mooney J, Sattar Z et al. Extending alcohol brief advice into nonclinical community settings: a qualitative study of experiences and perceptions of delivery staff. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3796-0

[18] Brown TJ, Todd A, O’Malley C et al. Community pharmacy-delivered interventions for public health priorities: a systematic review of interventions for alcohol reduction, smoking cessation and weight management, including meta-analysis for smoking cessation. BMJ Open 2016; 6(2):e009828. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009828

[19] World Health Organization. WHO alcohol brief intervention training manual for primary care. 2017. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/351294/Alcohol-training-manual-final-edit-LSJB-290917-new-cover.pdf?ua=1 (accessed June 2020)

[20] Connelly D. Drinking alcohol increases cancer risk. Pharm J 2018;300(7909). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2018.20204277

[21] Public Health England. Alcohol: applying All Our Health. 2019. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/alcohol-applying-all-our-health/alcohol-applying-all-our-health (accessed June 2020)

[22] Public Health England. Alcohol use screening tests. 2017. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/alcohol-use-screening-tests (accessed June 2020)

[23] Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J et al. AUDIT the alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary care. Second edition. (WHO/MSD/MSB/01.6a) World Health Organization, Geneva, 2001. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/67205/1/WHO_MSD_MSB_01.6a.pdf (accessed June 2020)

[24] Babor T & Higgins-Biddle J. Brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinking. A manual for use in primary care (WHO/MSD/MSB/01.6b). World Health Organization, Geneva, 2001. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/brief-intervention-for-hazardous-and-harmful-drinking-(audit) (accessed June 2020)

[25] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Alcohol: problem drinking. Clinical Knowledge Summary. 2018. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/alcohol-problem-drinking#!backgroundSub:2 (accessed June 2020)

[26] Committee on Carcinogenicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment (COC). Statement on consumption of alcoholic beverages and risk of cancer. 2015. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/490584/COC_2015_S2__Alcohol_and_Cancer_statement_Final_version.pdf (accessed June 2020)

[27] NHS UK. Live Well. Alcohol support. Calories in alcohol. 2020. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/alcohol-support/calories-in-alcohol/ (accessed June 2020)

[28] Prochaska J & Velicer W. The transtheoretical model of health behaviour change. Am J Health Promot 1997;2(1):38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38

[29] Stevely A, Buykx P, Brown J et al. Exposure to revised drinking guidelines and ‘COM-B’ determinants of behaviour change: descriptive analysis of a monthly cross-sectional survey in England. BMC Public Health 2018;18(1):251. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5129-y

[30] Michie S, van Stralen M & West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

[31] NHS UK. One You. 2020. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/oneyou/apps (accessed June 2020)

[32] Alcohol Change. Try Dry: the app to track your time off drinking. 2018. Available at: https://alcoholchange.org.uk/get-involved/campaigns/dry-january/get-involved/the-dry-january-app (accessed June 2020)

[33] NHS. Alcohol units. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/alcohol-support/calculating-alcohol-units (accessed June 2020)

[34] eLearning for Healthcare. About the alcohol identification and brief advice programme. 2017. Available at: https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/alcohol (accessed June 2020)