This content was published in 2010. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

In short

Wound dressings facilitate the body’s natural healing process and provide an optimal healing environment. The choice of dressing will vary depending on the wound’s characteristics and stage of healing (ie, necrotic, sloughy, infected, granulating or epithelialising). Equipped with the right knowledge pharmacists can help with the selection of appropriate dressings and identify factors that might impair healing.

Wound healing is a complex process, yet in healthy individuals its efficacy is rarely questioned. However, certain chronic illnesses (such as diabetes, Raynaud’s disease, heart disease and rheumatoid arthritis) and ageing make the skin more vulnerable to damage and slower to repair. Minor wounds usually heal within several weeks, but complicated wounds heal much slower.

Wound dressings facilitate the body’s natural healing mechanisms and provide an optimal healing environment; they do not heal wounds themselves. Additionally, no single dressing is suitable for all stages of healing, so effective management depends on good product knowledge and regular assessment.

The role of the pharmacist

Pharmacist interventions in wound care are important. In many institutions, there is not a clearly identified clinical team that takes ownership of wound management. Dressing selection is commonly decided by nurses because, often, general medical staff have a limited understanding of wound care.

Despite many dressings being classed as pharmaceuticals, most dressings are sourced directly from a hospital’s central stores rather than the pharmacy. Couple this with the fact that some dressings have important interactions with medicines and it stands to reason that a knowledgeable pharmacist can have a great impact on patient care.

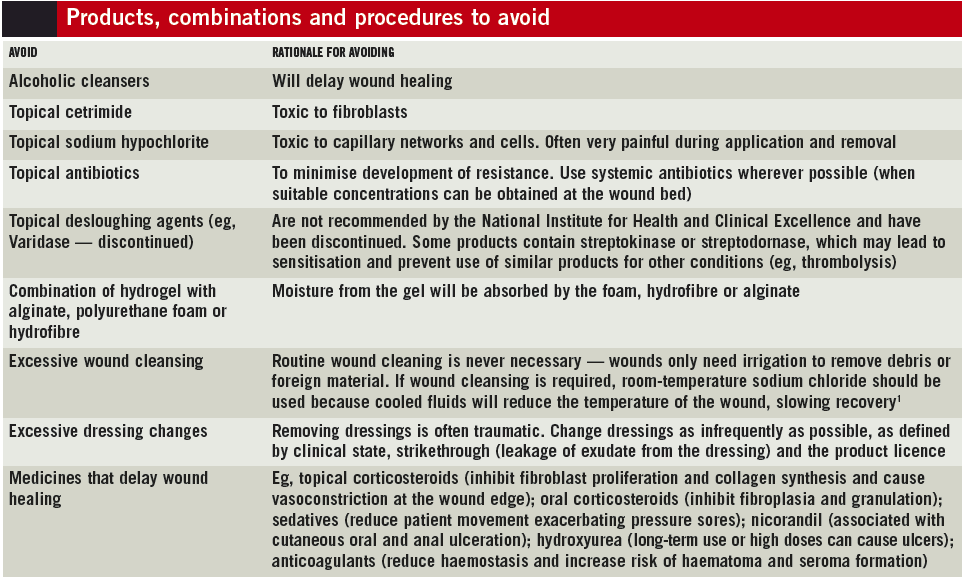

Furthermore, pharmacists can help identify factors that contribute to trauma and delayed wound healing (see Box).

Before selecting a dressing

Before selecting a dressing, the aims of treatment must be decided. Mostly, the goal will be to facilitate cosmetically acceptable healing in the shortest possible time. Other goals include: to remove extensive areas of necrosis, to ease pain and to eliminate foul odours. In all cases the aim should take into account patients’ prognoses and what they desire from treatment.

Factors that delay or prevent wound healing must also be identified and, where possible, minimised. Smoking, malnutrition and side effects of medicines slow recovery and pharmacists should be highlighting these issues to the multidisciplinary team.

Additionally, there are many types of wounds that will not heal until their underlying causes are addressed (eg, pressure ulcers will not heal until the pressure is relieved).

Dressing selection

The choice of dressing is influenced by many factors, but for practical purposes we need only consider three of them — wound-related issues, clinical effectiveness and economic factors. The latter two are usually tackled via the use of local formularies or trust guidelines and these should be adhered to wherever possible. Wound-related issues are complex but, in this article, have been simplified into the basic types discussed below.

Necrotic wounds

Under ideal conditions, dead tissue in a wound will autolytically debride from healthy tissue underneath. However, if dead tissue is exposed to a drying atmosphere it can dehydrate and shrink to form a hard black or olive eschar. The eschar can delay autolysis indefinitely and shrinking dead tissue can cause pain — therefore, the primary interventions for necrotic wounds involve rehydrating the wound and removing hard, dead tissue.2

Surgical removal (debridement) can enable access to healthy well perfused tissue. However, necrotic tissue can be a sign of poor vascular function and the risk of recurrence is high.

Hydrogel dressings have a 60–90% water content and draw moisture through the wound, rehydrating the eschar and making it easier to remove. Hydrogel dressings are available as amorphous gels (eg, GranuGel, Nu-gel), impregnated nonwoven dressings (eg, Intrasite conformable) and sheets (eg, Novogel). Most commonly amorphous gel is used, which is then covered with a secondary dressing to hold it in place and reduce moisture evaporation. Barrier preparations such as white soft paraffin can be used to protect nearby healthy skin from maceration.

Suitable secondary dressings include perforated plastic film adsorbent dressings (eg, Melonin, Telfa) or vapour-permeable films (eg, Tegaderm, OpSite, Bioclusive).

It is important to remember that hydrogels contain the preservative propylene glycol, which will mean that larval therapy cannot be used once the wound becomes sloughy (because propylene glycol is toxic to larvae).

Necrotic wounds rarely have high levels of exudate but, if the wound has a mixed presentation, large amounts can be produced. In this case, an alginate dressing (eg, Sorbsan, Kaltostat, SeaSorb) may be more appropriate than a hydrogel or hydrocolloid dressing.5 Derived from seaweed, alginates can absorb large amounts of exudates yet maintain a moist wound environment. There are a variety of alginate dressings, such as ribbons and sheet dressings, and an assortment should be used to pack the wound. Alginates are not suitable for dry wounds since they can stick to the wound and cause trauma when removed.

Regardless of the approach used, when the necrotic eschar eventually separates from the healthy tissue, it leaves a wound bed containing yellowish, partly liquefied material (“slough”). Sloughy wounds are treated differently, as discussed below.

Necrotic digits

Unlike other necrotic tissues, necrotic digits should not be rehydrated or the tissue may become a focus for infection. The affected digit should be left exposed to the air to provide optimal conditions for auto-amputation (ie, the spontaneous separation of non-viable tissue from viable tissue, such as the spontaneous detachment of a frostbitten toe) or surgically removed if extensive tissue destruction is identified. In most cases a vascular assessment is vital.

A suitable alternative to hydrogel dressings are hydrocolloid dressings (eg, Granuflex, Comfeel, DuoDERM), which are occlusive and waterproof. They prevent water evaporation and promote moisture accumulation thereby rehydrating the tissue. Hydrocolloid dressings are not recommended for dry wounds or use over exposed bone or muscle. Because they are occlusive, they may promote overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria so are contraindicated for infected wounds.3,4 Most hydrocolloid dressings contain gelatine from pigs so may not be acceptable to vegans and people of certain faiths.

If the edges of the wound are moist, an iodine dressing (eg, Inadine) and a dry secondary dressing can be applied to fight infection or reduce pain. A low- or nonadherent product (eg, N-A Ultra, Mepitel) can be used as a single dressing if the patient is in significant pain.

Sloughy wounds

Slough is a complex mixture of fibrin, proteins, serous exudates, leucocytes and bacteria. It can build up rapidly on the surface of previously clean wounds and be too thick to be removed by swabbing or irrigation. Slough acts as a bacterial growth medium, so affected wounds should be properly treated to enable wound healing.

Sharp surgical cleaving of sloughy matter is quick but not always practical. Other management techniques aim to support the natural processes that debride slough and to manage the exudates resulting from the inflammatory stage of wound healing. It is important not to overhydrate the wound to avoid maceration leading to further tissue breakdown.

Alginates covered with either a semipermeable film dressing or a hydrocolloid dressing will maintain a moist healing environment and draw away excess exudates. In moderately or heavily exudating wounds, a hydrofibre dressing (eg, Aquacel) can be used in combination with an absorbent secondary dressing. Hydrofibre dressings can absorb large amounts of fluid, even under pressure. Because little fluid is drawn laterally, nearby tissues do not become macerated. Hydrofibre dressings can be removed with little or no damage to newly formed tissue.6,7

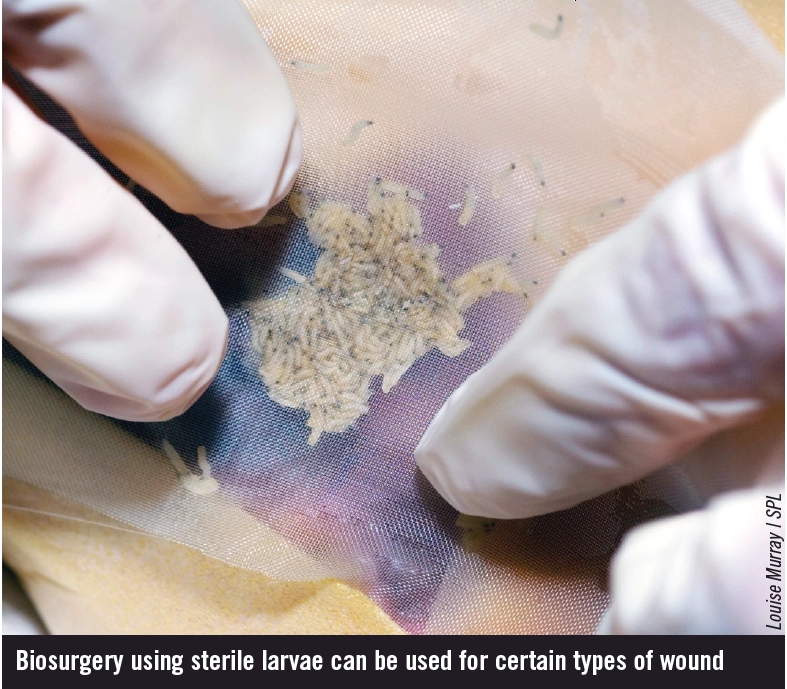

Biosurgery, also known as larval therapy or maggot therapy, is suitable for use on a variety of necrotic and sloughy wounds — although patients may be reluctant to accept them at first. Sterile larvae exude enzymes that break down dead tissue, thereby combating odour and killing bacteria. Normal, healthy tissue is not affected, but may be irritated by the enzymes (Sudocrem can be used as a barrier on surrounding tissue). A secondary dressing should be used to absorb exudates and keep the larvae in the wound. This dressing should also be non-occlusive because larvae require oxygen to breathe.8 Modern “maggot kits” are available, which contain everything needed for the treatment. Analgesia is often required because of increased pain caused by pH changes in the wound as a result of biosurgery. The pain will decrease as the bacterial load in the wound reduces. Despite concerns, patients cannot feel the maggots “nibbling”.

Infected wounds

For infected wounds, systemic antibiotics are indicated in addition to an antimicrobial dressing. In all cases, a wound swab should be sent for culture and sensitivity testing. Topical antibiotics, such as mupirocin and metronidazole, are rarely used because of concerns about microbial resistance. However, metronidazole gel 0.75% can still be useful for reducing the odour of fungating wounds that are colonised with anaerobes.9

Charcoal dressings (eg, CliniSorb, CarboFLEX) can also be used to reduce odour, but some are only suitable for use as a secondary dressing. Additionally, charcoal dressings can stick to wounds if they are allowed to dry out, causing substantial trauma when removed.10 Antimicrobial dressings contain one of the following active ingredients:

Iodine

Iodine dressings are contraindicated in hypersensitive patients, pregnant or breastfeeding women and those with thyroid disorders or renal impairment. T3 and T4 levels should be monitored. Iodine can alter lithium levels. Examples include povidoneiodine sheets (Inadine) and cadexomeriodine paste (Iodoflex) or powder (Iodosorb).

Silver

When silver dressings come in contact with exudates, silver (an antibacterial and antifungal) is released. Although expensive, these dressings are effective and are useful as a supplement to systemic therapies, which may have difficulty reaching therapeutic levels in the wound bed (especially for patients with poor vascular perfusion). Avoid in patients with silver allergies and use with caution in renally impaired patients since silver can accumulate over time.11

Honey

Sterilised honey dressings maintain a moist healing environment, eliminate odour, stimulate new tissue growth and aid debridement.12 The use of these dressings is limited by pain on application, high cost and bee sting allergy.

Granulating wounds

Granulation tissue is a fragile mixture of proteins and polysaccharides linked together with collagens to form a highly vascular gel-like matrix with a characteristic red appearance. Granulating wounds must be kept warm and moist and exudates must be managed. The size, shape and amount of exudate in a granulating wound can vary considerably.

Low-depth wounds should be protected with a low- or non-adherent dressing or a hydrocolloid. Occlusive hydrocolloids are particularly effective because they create a hypoxic environment, which promotes granulation. If exudate is heavy, alginates can be used. Dressings should be changed as infrequently as possible to prevent damage to the fragile wound bed.

For deep cavity granulating wounds, a polyurethane foam dressing (eg, Allevyn, Lyofoam, Tielle) can be used to pack the wound. These usually consist of foam or foam chips enclosed within a soft flexible pouch to allow entry of exudates. It is important not to overpack the wound because this can cause wound distortion leading to ischaemia, necrosis, cosmetic defects and patient discomfort.

Granulation continues until the base of the wound cavity is almost level with the surrounding skin. At this point, the wound begins epithelialisation.

Epithelialising wounds

In the final stage of wound healing, epithelial cells advance in a sheet across the wound, starting at the wound margins before meeting in the middle. The length of time this process takes depends on the extent of tissue damage. This process does not tend to produce large quantities of exudate. The aim for this stage of healing is to keep the wound moist until it closes.

Superficial wounds can be managed easily with hydrocolloids or one of the semipermeable dressings mentioned previously. It should be remembered that this tissue is still delicate, so care should be taken to avoid trauma when changing the dressings.

Other dressings useful in the final stages of healing include soft silicone dressings (eg, Mepitel), knitted viscose preparations (eg, N-A dressing, Tricotex) and nylon sheet dressings (eg, Tegapore). Remember to check for nylon, silicone or viscose allergies. Whichever dressing is used, the wound should be monitored regularly for signs of infection or deterioration.20

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Claire Richardson (senior staff nurse), Barbara Topley (tissue viability sister) and Jane Marshall (directorate pharmacist for the department of medicines for older persons) for their comments and review of this article.

References

- McGuiness W, Vella E, Harrison D. Influence of dressing changes on wound temperature. Journal of Wound Care 2004;13:383–5.

- Bishop SM, Walker M, Rogers AA, et al. Importance of moisture balance at the wound-dressing interface. Journal of Wound Care 2003;12:125–8.

- Hutchinson JJ, Lawrence JC. Wound infection under occlusive dressings. Journal of Hospital Infection 1991;17:83–94.

- Kannon GA, Garrett AB. Moist wound healing with occlusive dressings. A clinical review. Dermatologic Surgery 1995;21:583–90.

- Morgan D. Alginate dressings. Journal of Tissue Viability 1996;7:4–14.

- Robinson BJ. The use of a hydrofibre dressing in wound management. Journal of Wound Care 2000;9:32–4.

- Tong A. Recognising, managing and removing slough. Nursing Times 2000;96(29 suppl):15–16.

- Falch BM, De Weerd L, Sundsfjord A. Maggot therapy in wound management. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening tidsskrift for praktisk medicin ny raekke. (Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association) 2009;129:1864–7.

- Ashford RF, Plant GT, Maher J, et al. Metronidazole in smelly tumors. The Lancet 1980;1:874–5.

- Thomas S, Fisher B, Fram P, et al. Odour absorbing dressings: A comparative laboratory study 1998. www.worldwidewounds.com/1998/march/Odour- Absorbing-Dressings/odour-absorbing-dressings.html (accessed 27 September 2010).

- Lansdown ABG, Williams A, Chandler S, et al. Silver absorption and antibacterial efficacy of silver dressings. Journal of Wound Care 2005;14:155–60.

- Molan PC. The role of honey in the management of wounds. Journal of Wound Care 1999;8:415–8.

- Lay-Flurrie K. Wound management to encourage granulation and epithelialisation.

NOTE

Clinical Pharmacist PRACTICE TOOLS do not constitute formal practice guidance. Articles in the series have been commissioned from independent authors who have summarised useful clinical skills.

You might also be interested in…

How to support patients taking new oral anticoagulant medicines