Alamy Stock Photo

Historically, GP practices recorded information about a patient’s medication and allergies on paper, but over the last 30 years, GP surgeries have migrated their records onto computer systems allowing better management of patient information. They use a variety of different patient record management systems, however a lack of uniformity makes sharing information outside the individual practice challenging.

Often when patients present with urgent or emergency care needs, GP practices are closed and healthcare practitioners cannot access the information they require to care for the patient. The summary care record (SCR) is a centrally held record containing key information about a patient which can greatly improve the timeliness and safety of care given to patients by pharmacists. It has been available for use in secondary care for a number of years and has revolutionised how information about a patient’s medication is used[1]

,[2]

.

In April 2014, NHS England decided to trial the use of the SCR in community pharmacies[3]

,[4]

to provide emergency supply, supporting additional pharmacy services (e.g. the new medicines service [NMS] and minor ailments service) and providing patients with consistent information about their usual medications. The SCR can support community pharmacists to deliver patient centered services, which could ease pressure on other parts of the health service. Pharmacy stakeholders involved in the trial concluded that all community pharmacies should have access to SCR[4]

. Subsequently, implementation of SCR access to all community pharmacies commenced in autumn 2015 and should be complete by autumn 2017[3]

.

What is the SCR?

The SCR is for patients who have a registered GP in England. Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland have equivalents of the SCR, but currently there are no plans for community pharmacists to have access to them. As part of the GP contract, all practices are required to produce SCRs for patients, and as of January 2016, 96% of patients have had their records uploaded[5]

. Every time a patient’s record is updated at the GP practice the SCR is also updated, although there may be a small delay as the GP practice needs to complete an authentication process. Patients have been given the option of opting out of having a SCR, but in practice less than 1% of the population have made this decision[6]

.

The core information that is stored on the SCR includes demographic details about the patient, medication information (current repeat medication, acute medication and recently discontinued medicines), allergy information and any adverse reactions (see ‘How information is displayed on the SCR’ for more information). It is essential that health professionals understand that the information contained on the SCR is populated directly from the GP record. This means that other sources of information, such as hospital notes, will not appear on the system until the GP surgery has included it. The SCR is time-stamped to indicate when it was last updated, and individual patients can request additional clinical information from the GP record is added to it. This includes diagnosis or care plans that it would be beneficial to share[7]

.

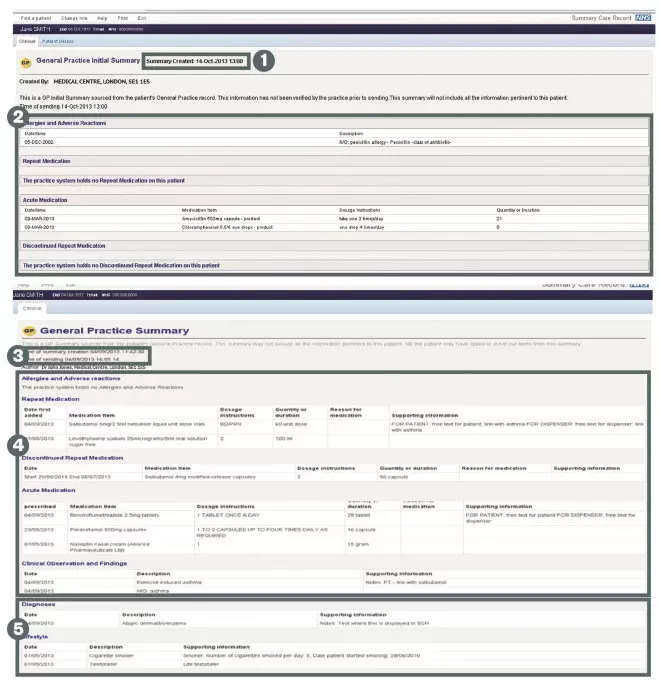

How information is displayed on the Summary Care Record (SCR)

Source: Images reproduced with the permission of the Health and Social Care Information Centre. Copyright 2015. All rights reserved.

In order to view clinical information on the SCR, healthcare staff need to use a smart card with the correct role, identify and locate the correct patient, have the patient’s permission to view their SCR and have a legitimate relationship with the patient (e.g. be directly involved in their care)

1) Time and date indicates clearly when the SCR was last updated by the GP practice

2) Core information relating to this patient, including allergies and adverse reactions, repeat medications, acute and discontinued medications

3) Time and date stamp indicates when the SCR was last updated by the GP practice

4) Core patient information

5) Additional clinical information may be included from the GP record including significant diagnoses, lifestyle or care plans if the patient has given their consent

Key points to remember when viewing a Summary Care Record (SCR)

- SCR is a summary and not a full detailed patient record

- SCR may not contain all information for a patient (e.g. medications prescribed outside GP practice)

- The information is accurate at the time of creation – clear from time/date stamp – and users should check for subsequent information as part of normal history taking

How to access the SCR?

Pharmacy access to the SCR is restricted to registered professionals only (i.e. pharmacists and technicians). All pharmacy professionals wishing to access a patient’s SCR must have completed the relevant Centre for Pharmacy and Postgraduate Education (CPPE) e-learning package[8]

. The SCR application is web based and can be accessed through the NHS Spine portal. To facilitate access, pharmacy professionals require a smart card with the relevant roles assigned and a secure network connection. All technical and access issues are addressed by specialist roll-out teams when an area or organisation is starting to use SCRs. Training will be provided before an organisation’s access goes live, by the roll out team. Locum access can also be arranged, however specific information governance requirements must be met. Further information is available from the Health and Social Care Information Centre.

Once the NHS Spine portal has been accessed, the pharmacy professional can search for patients using a variety of different demographic parameters (see ‘How information is displayed on the SCR’). To view any patient’s medical information the staff member needs to be involved in their care, this is called a ‘legitimate relationship’. Legitimate relationships are automated within the different viewing software, allowing reports to be produced for privacy officers to ensure access is being used appropriately.

The General Pharmaceutical Council has issued a statement relating to the responsibilities of pharmacists, pharmacy technicians and pharmacy owners in relation to access to the SCR. This statement also includes information on liability[7]

. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has also outlined these responsibilities in its own SCR resources[9]

.

Permission to view

A patient must give explicit permission to each pharmacy professional before they view a SCR, based on need. This can be given either in person or over the telephone, and pharmacists or pharmacy technicians will usually record permission to view on the SCR system. However some organisations may additionally choose to record permission to view either by documenting electronically on the pharmacy local computer systems (for instance the patient medication record [PMR]) or by asking the patient to sign a paper form confirming their agreement to access. It is acceptable practice to ask regular patients, for whom you think you will need to access their SCR frequently, for permission to view their SCR for the length of time they are under your care.

Permission to view is based on clinical need, in a community pharmacy this would not be for routine dispensing. It will be up to the individual pharmacist’s professional judgement to determine the clinical need for their patients[9]

,[10]

. See ‘Examples of how SCRs may be used’.

All patients in England have the choice to opt-in or opt-out of having an SCR at any time. If a patient decides that they would like to opt-out of having an SCR altogether, then they should be advised to contact their GP practice who will record this.

Examples of how SCRS may be used

Example 1

A patient is visiting friends and has forgotten their inhalers. They attend a community pharmacy and request an emergency supply. The pharmacist views their SCR and can see they had inhalers supplied two weeks ago. The pharmacist provides an emergency supply and advises on dose and frequency. The time it takes to carry out the consultation is reduced because the information is quickly accessed on the SCR, eliminating the need to either contact the GP or refer the patient to urgent care services.

Example 2

A patient presents for a flu jab in their community pharmacy. The pharmacist checks their SCR and identifies that they have a chronic chest problem, which makes them eligible for a free flu jab. The pharmacist administers the vaccine and informs the patient’s GP of the consultation to allow the relevant records to be updated. Access to the SCR reduces the need for delays in obtaining information and prevents unnecessary referrals to other NHS services.

Example 3

A patient receives a prescription from a dentist for antibiotics. They cannot remember what they are allergic to, so the community pharmacy accesses their SCR. The patient is allergic to penicillin, allowing the pharmacist to confirm if their current prescription is safe. Access to the SCR allows the treatment provided to be more informed, reduces the need to contact other NHS services and reduces the time taken to ensure the prescription is safe.

Emergency access

There is an option to access the SCR without obtaining explicit permission from patients. This route is known as ‘emergency access’ and can be used when it is believed there is a valid clinical need to view the SCR but the patient is unable to give consent.

On these occasions, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians would be expected to use their professional judgement to decide whether the quality or safety of a patients care could be compromised without viewing the information held on the SCR. If it is deemed necessary, then the emergency access route can be used, at which point it is strongly recommended that the reason for access without permission is recorded.

Some examples of using emergency access appropriately in community pharmacies include patients with cognitive impairment due to dementia or patients with language difficulties.

Communicating decisions with the GP

As pharmacists and pharmacy technicians working in the community pharmacy setting have read-only access to the SCR, they should continue communicating their decisions with GPs in the same manner in which they currently do (e.g. the issue of an emergency supply). This will help to ensure that strong relationships are maintained with GP’s.

Information governance

Each pharmacy organisation implementing SCR access must allocate a person to perform the privacy officer role. This person then holds the responsibility for monitoring the SCR viewing activity of their associated users.

The SCR system uses audit, alerts and reporting to ensure that the governance relating to record access and viewing are adhered to. The Privacy Officer will be allocated access rights on their smartcard in order to perform the activities required to manage alerts and monitor SCR viewing activity.

When a user overrides one of the information governance controls that are in place in the SCR system, alerts are generated. Examples of governance controls which, when overridden will trigger an alert include: clinicians self claiming a legitimate relationship or emergency access of a patient’s SCR without permission. Alerts are viewed by the privacy officer on a system database known as the ‘alert viewer’ and contain details relating to the user who accessed the record, the time and date, the organisation they are associated with, and the patient’s NHS number for whom they accessed the SCR. On receiving an alert, the privacy officer is expected to review and validate the detail in order to identify whether the access was appropriate[11]

.

If the investigation shows that an SCR access is potentially inappropriate, then this should be escalated for investigation to ascertain whether there has been a confidentiality breach. Breach of confidentiality and unauthorised access may lead to disciplinary action. The majority of alerts can be closed when proof of a valid legitimate relationship or reason for emergency access has been proven.

In addition to investigating individual alerts, privacy officers can run a number of reports which give an overarching impression of an organisation’s viewing habits.

How can pharmacy access to the SCR benefit practice?

Having a strong relationship with community pharmacy and GP practices is essential. SCR access should be regarded as an extra tool to help the pharmacist to help improve patient care. Use of the SCR has already demonstrated improvements in care provided by hospital and community pharmacy[4]

,[12]

.

During the community pharmacy pilots SCR access was used for a range of services including emergency supply, NMS, minor ailments, clarifying a prescriber’s intent and to allow accurate advice provision for patients. On average 2.9 SCRs were accessed each month, with a higher proportion being used out-of hours[4]

. Pharmacists stated that it should not replace the existing communication methods in existence with GP practice.

There are four key areas where access to the SCR will benefit practice. These are:

Patient safety

A pharmacist is able to access a patient’s SCR when they suspect a prescribing error, to help clarify the prescriber’s intention. In the community pharmacy pilot, 85% of pharmacists felt that SCR access contributed to improving patient safety[4]

.

Efficiency of patient care

A pharmacist is able to access a patient’s SCR to confirm a medication when they are requesting an emergency supply. When community pharmacy respondents who participated in the pilot were asked, 92% felt that SCR enabled them to treat patients more effectively when GP practices were closed[4]

.

Effectiveness of patient care

A pharmacist is able to access a patient’s SCR when they present for a minor ailment service and to confirm usual medication, allowing the pharmacist to provide treatment. Some 90% of pharmacists who participated in the pilot agreed that using the SCR meant they could resolve issues without signposting to other services[4]

.

Patient experience

A pharmacist accesses a patient’s SCR to confirm the details of their usual medication as they were unsure, allowing a far more timely answer to be provided to the patient. Of the community pharmacy respondents in the pilot, 92% felt that SCR improved the service they provided[4]

.

David Gibson is lead clinical pharmacist, Darlington Memorial Hospital, Hollyhurst Road, Darlington, County Durham, DL3 6HX and Laura Smith is lead pharmacist (patient safety), Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Delargy K & Parekh R. Summary care record viewing in a mental health trust. Hospital Pharmacy Europe 2015:Issue 77. Available at: http://www.hospitalpharmacyeurope.com/medicines-reconciliation/summary-care-record-viewing-mental-health-trust (accessed April 2016).

[2] Andalo D & Sukkar E. Risks and benefits of pharmacists accessing patients’ summary care records. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2015;295(7870). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2015.20068889

[3] Health and Social Care Information Centre. SCR in community pharmacy (2015). Available at: http://systems.hscic.gov.uk/scr/pharmacy (accessed April 2016).

[4] Health and Social Care Information Centre. Community Pharmacy Access to Summary Care Record- Proof of Concept Report (2015). Available at: http://systems.hscic.gov.uk/scr/pharmacy/cppilot.pdf (accessed April 2016).

[5] Health and Social Care Information Centre. Summary Care Record overview (2016). Available at: http://www.systems.hscic.ov.uk/scr/highlights.pdf (accessed April 2016).

[6] Health and Social Care Information Centre. Information request (2015). Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/media/19892/NIC-363485-C3Q1S-ResponseRedacted/pdf/NIC-363485-C3Q1S_Response_Redacted.pdf (accessed April 2016).

[7] Health and Social Care Information Centre. SCR and community pharmacy: factsheet (2015). Available at: http://systems.hscic.gov.uk/scr/pharmacy/cpfactsheet14.01.pdf (accessed April 2016).

[8] CPPE. Summary Care Records in Community Pharmacy (2015). Available: https://www.cppe.ac.uk/programmes/l/summary-e-01/ (accessed April 2016).

[9] RPS/NPA. Electronic health records: Guidance for Community pharmacist and pharmacy technicians (2012). Available at: http://www.rpharms.com/promoting-pharmacy-pdfs/electronic-health-records-guidance-dec2012.pdf (accessed April 2016).

[10] RPS. Using electronic health records professionally (2016). Available at: http://www.rpharms.com/support-pdfs/scr-england.pdf (accessed April 2016).

[11] Pharmacy Voice. Governance of shared care records (2016). Available at: http://psnc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/PV_Governance_of_Shared_Care_Records_January_20161.pdf (accessed April 2016).

[12] RPS. Summary Care record (2015). Available at: http://www.rpharms.com/unsecure-support-resources/summary-care-records.asp (accessed April 2016).