This content was published in 2006. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an auto-immune disorder causing impaired neuromuscular transmission in skeletal muscle. The term, derived from Greek and Latin, means grave (gravis) muscle weakness (myasthenia). MG can occur at any age, although it is rare under the age of 10 years. There are peak incidences between 10 and 30 years (where more women than men are affected) and 60 and 70 years (where more men are affected). The condition is not hereditary but genetic factors play a part and the risk of developing MG is slightly increased for close relatives of autoimmune disease sufferers.

Symptoms

Patients with MG complain of specific muscle weakness but not general fatigue. This weakness worsens with repeated or sustained use of the muscle. It is typically worst at the end of the day and improves with rest.

In two thirds of patients with MG, the muscles controlling eye and eyelid movement are the first to be affected. The patient experiences intermittent drooping of the eyelids (ptosis; see Figure 1) and double vision, which worsens during the day or with repeated or focused use (eg, after driving, reading or watching television) and is aggravated by tiredness. Other initial symptoms include difficulty chewing, swallowing, smiling or talking (the voice often has a nasal tone) and loss of facial expression (a smile can look like a grimace), as a result of oropharyngeal muscle weakness. This occurs in one sixth of patients. Limb weakness, mainly of the upper body, is the presenting symptom in one tenth of cases and, typically, these patients have difficulty raising their arms above their head.

Patients experience periods of relapse and remission. In remission, they can lead normal or near normal lives. Symptoms fluctuate and tend to worsen in hot weather, during or immediately after infections, before menstruation and after childbirth. Symptoms can also change during pregnancy: they worsen in a third of patients and improve in a third.

Identify knowledge gaps

- What impact can myasthenia gravis have on daily activities?

- How is myasthenia gravis managed?

- What drugs can exacerbate symptoms

Before reading on, think about how this article may help you to do your job better. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s areas of competence for pharmacists are listed in “Plan and record”, (available at: www.rpsgb.org/education). This article relates to “using knowledge and skills to benefit patients” (see appendix 4 of “Plan and record”).

Occasionally, MG resolves spontaneously, but for most patients the condition is life-long. If symptoms affect only the eye muscles for longer than two years, the condition is unlikely to spread and the patient is said to have ocular myasthenia. However, in 90 per cent of cases other muscles are involved, with weakness typically spreading down to the lower face, neck and throat and, sometimes, the skeletal muscles of arms and legs, and elsewhere — this is known as generalised MG. Patients can be droopy, listless and unable to perform everyday activities.

Weakness in chest muscles, if severe, can cause a myasthenic crisis, where difficulties breathing can be life-threatening. Crises are seen less often now that treatment with immunosuppressants is used (see below) but they may occur with worsening disease or infection. Respiratory failure can be sudden and any dypsnoea, or more dysphagia than usual, should be quickly investigated.

Diagnosis

MG is a rare disease affecting one in 20,000 people in the UK. However, almost all patients are treated with drugs so pharmacists should be aware of the condition.

Because initial symptoms are commonly droopy eyelids and double vision, optometrists as well as GPs are consulted. Clinical signs may not be evident at the time of consultation because symptoms can fluctuate within a day and from day to day. The symptom history, however, often suggests MG. Confirmation and diagnosis requires referral to a neurologist. Referred patients are observed and have their antibody status assessed.

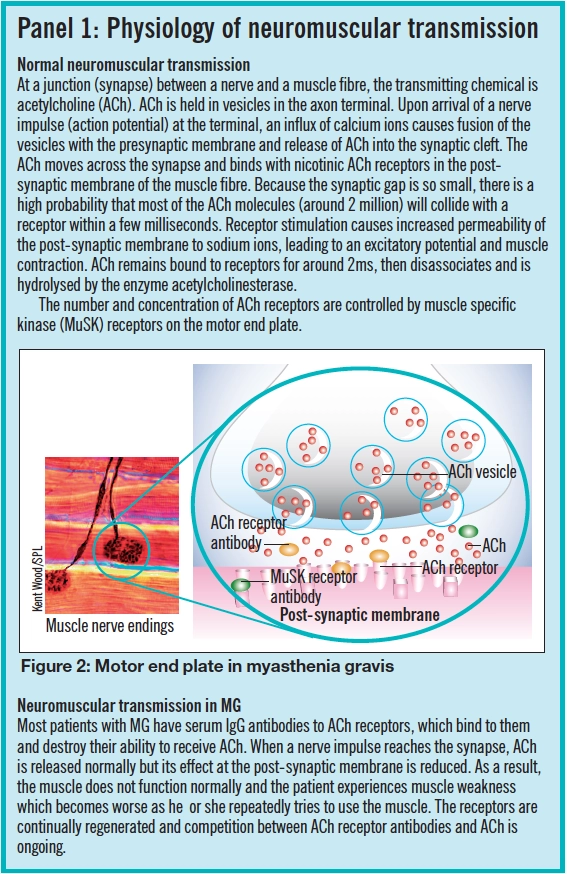

Serum IgG antibodies to acetylcholine (ACh) receptors are seen in about 85 per cent of patients with generalised MG and 50 per cent of those with ocular MG.1 Around half those without identifiable ACh receptor antibodies have muscle specific kinase receptor antibodies (MuSK; see Panel 1). Patients with these antibodies are more likely to be female and under 40 years of age.

Electromyography, which measures the level of muscle contraction in response to electrical stimulation, is also used in diagnosis. In patients with MG, response diminishes with repeated stimulation. Other diagnostic methods include the Tensilon test where intravenous edrophonium is administered. This gives a marked short-lived (about five minutes) improvement in muscle power in MG patients. Chest scans in MG patients often show an enlarged thymus (70 per cent of patients) or the presence of a thymic tumour (10 per cent).

Treatment

Of all the autoimmune diseases, MG is the best understood (see Panel 1) and can be managed effectively with drugs. There is a three-pronged approach to treatment:

- Prescribing an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (anticholinesterase)

- Immune suppression

- Surgical removal of the thymus (thymectomy)

Anticholinesterases

The first-line drug treatment for MG is with an anticholinesterase to prolong the presence of ACh in the neuromuscular synapse. Pyridostigmine is the preferred drug because it has a smoother dose response curve and longer duration of action than neostigmine and fewer gastric side effects. (The effect of neostigmine tends to drop rapidly after it peaks and this can complicate the timing of doses.)

Gastric side effects, such as diarrhoea andabdominal cramps, are the most frequent reason for patients wanting to stop taking an anticholinesterase. Other side effects include bradycardia, sweating and increased salivary and gastric secretions. Many of these side effects are caused by the drug acting at muscarinic receptors so an antimuscarinic, such as propantheline, is sometimes co-prescribed if side-effects are troublesome, but prescribing requires the close supervision of a neurologist.

Starting doses of pyridostigmine are low. In most clinics, doses are gradually increased according to a regimen that has been found to reduce the incidence of side-effects: 30mgbd for two days; then 30mg five times a day for four days; then alternating 60mg and 30mg doses, five times a day for six days; then increasing to 60mg five times a day. Clinicians call this the “2-4-6 induction regimen”. The patient can stop increasing and maintain the dose at a level that achieves acceptable symptom reduction and the fewest unacceptable side effects.

The need for anticholinesterases varies. Doses can require frequent adjustment according to individual response to the drug, symptom fluctuation and activity levels. Different muscles respond differently; with any dose, some muscles become stronger whereas others do not, and others still might become weaker. Care must be taken with dosing because excessive doses can cause a depolarising block (the muscle no longer responds due to overstimulation) and precipitate a cholinergic crisis (paralysis and respiratory failure), which can be difficult to distinguish from worsening MG symptoms.

The total daily dose of pyridostigmine should not usually exceed 450mg and if the total daily dose required for satisfactory symptom control exceeds 360mg, immunosuppressant therapy is indicated (see below).

Edrophonium, used in the diagnosis of MG, can also be used to find out if a patient’s treatment dose is inadequate (it results in a short-lived improvement) or excessive (it has no effect or intensifies symptoms).

Anticholinesterases are contraindicated inpatients with asthma, cardiac conduction defects, urinary and intestinal obstruction.

Corticosteroids

Most patients do not achieve satisfactory control of their symptoms with pyridostigmine alone and require a corticosteroid to suppress antibody production. The drug of choice is prednisolone, which is effective at reducing or eliminating symptoms and may modify the long-term course of the illness. Starting doses are low (initially 10mg on alternate days) and increased gradually (to1–1.5mg/kg and a maximum of 100mg on alternate days) until symptoms are controlled. Around 10 per cent of patients experience a worsening of symptoms for the first two to three weeks of treatment but then symptoms start to improve and a maximum therapeutic response is seen after two to six months. Once remission is achieved, the dose can be gradually reduced to the lowest effective level (10–40mg on alternate days, according to the British National Formulary, but in practice lower doses can be sufficient when used alongside other immunosuppressants).

Prednisolone is a long-term treatment andpatients should receive concurrent osteoporosis prophylaxis and gastric protection.

In cases of ocular MG pyridostigmine alone can be sufficient to alleviate symptoms, but early treatment with a corticosteroid can reduce the likelihood of progression to generalised MG.

Other immunosuppressants

Azathioprine is used to manage more severe cases of MG. It allows lower steroid doses so is often started at the same time as prednisolone in generalised MG. Doses are started low and increased to 2–2.5mg/kg daily over three to four weeks. Some clinical improvement is seen after three to nine months but maximum effect may not be achieved for up to three years.

Methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil (unlicensed indication) are used as alternatives to azathioprine. Ciclosporin is used as a third choice. Patients taking immunosuppressants require regular blood tests to monitor for signs of myelosuppression (eg, anaemia or leucocytopenia).

Thymectomy

The thymus gland is a small gland in the upper chest and, along with the rest of the endocrine system, it maintains a healthy immune system. The main role of the normal thymus is to aid the proliferation and differentiation of mature T-lymphocytes. Therole of T-cells from the thymus is to turn on B-cells to make antibodies. It is likely that abnormal T-cell development is responsible for triggering MG. However, thymectomy does not always improve MG symptoms, so the disease is clearly more complex.

Thymic tumours are usually slow-growing tumours with low malignancy but they are nearly always removed as early as possible to prevent spread. Some patients without a thymoma also benefit from removal of the thymus if they show positive for the ACh receptor antibodies. Removal of the thymus is most likely to give improvement in symptoms if the patient is under 45 years and has generalised MG with identified ACh receptor anti-bodies and has had MG for less than one year.1

Other treatments

Intravenous immunoglobulin (unlicensed indication) results in an improvement in symptoms and is used to treat severe relapses. High dose intravenous immunoglobulin (2g/kg infused over three to five days) is thought to down-regulate antibodies associated with MG. Symptom improvement is seen in at least 50 per cent of patients after one week and can last several weeks or months. However, treatment is expensive.

Plasma exchange (plasmapheresis) to remove the ACh receptor antibodies from the blood, is sometimes used to give symptom relief. It is also used in a myasthenic crisis along with intravenous corticosteroids. The improvement in symptoms can last up to eight weeks.

Non-pharmaceutical strategies for ocular symptoms include eyelid tape and ocular crutches attached to glasses, to hold the eyelids up.

Drug interactions

If a patient’s MG is well controlled he or she is unlikely to experience problems with drug-disease interactions, with the exception of penicillamine, which should be avoided. The other interaction worthy of particular note is if a myasthenic crisis has been brought on by infection and one of the antibiotics mentioned in Panel 2 is used to treat it. Other drugs that have been linked with worsening MG symptoms include: erythromycin, phenytoin, calcium channel blockers and morphine.

MG is of particular significance to anaesthetists because they administer drugs that affect neuromuscular junctions. The possibility of residual anaesthetic when administering drugs for MG after surgery must be borne in mind.

Conclusion

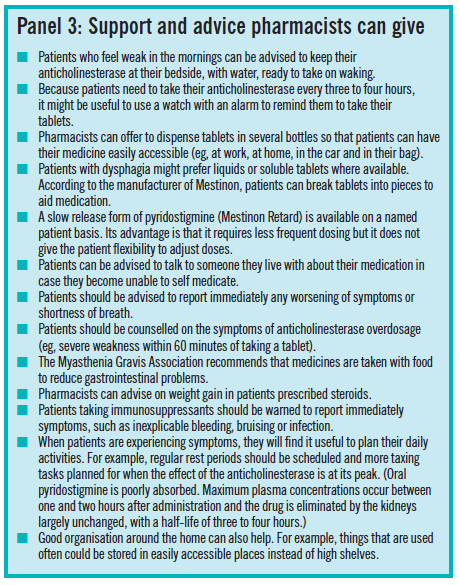

Although MG is usually a life-long condition, with treatment most patients are able to live near normal lives. As well as being aware of potential interactions, pharmacists can offer practical support and advice to patients and carers. Examples are listed in Panel 3.

Acknowledgements

Kate Fraser, myasthenia gravis nurse specialist, Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Liverpool, and Juan Esquivel, medical manager, Valeant Pharmaceuticals.

Resources

Further information, including details of research and support, is available through the Myasthenia Gravis Association UK (www.mgauk.org)

References

- Buckley C. Diagnosis and treatment of myasthenia gravis. Available at www.escriber.com (accessed 4 December 2006).

- Fiekers J. Effects of the aminoglycoside antibiotics, streptomycin and neomycin on neuromuscular transmission. I. Presynaptic considerations. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 1983;225:487–95.

Action: practice points

Reading is only one way to undertake CPD and the Society will expect to see various approaches in a pharmacist’s CPD portfolio.

- Communicating with patients with MG can be difficult. Think about how you could improve communication with a person with impaired speech and an unusual facial expression.

- Make sure patients who regularly take steroids carry a steroid card.

- Read the patient information leaflet for Mestinon. What should a patient who has missed a single dose be advised to do?

Evaluate

For your work to be presented as CPD, you need to evaluate your reading and any other activities. Answer the following questions:

What have you learnt?

How has it added value to your practice? (Have you applied this learning or had any feedback?) What will you do now and how will this be achieved?