McLean/Shutterstock.com

Ear problems are common and patients often seek advice about managing their symptoms from community pharmacies. In 1998, a cross-sectional self-completed questionnaire was sent to 12,100 UK households. Hearing problems, dizziness and tinnitus are common problems for people living in the UK. Data from the survey show that almost 20% of the 15,788 respondents in Scotland had experienced one of these symptoms; this suggests that there is a large number of people in the UK living with ear problems who may benefit from the advice of a pharmacist[1]

.

Recent campaigns, such as ‘Stay well pharmacy’, have sought to encourage people — particularly parents and carers of children under the age of five years — to visit their local pharmacy first for minor health concerns rather than consult their GP[2]

. While making a diagnosis can be challenging, given the limited number of examinations possible by a pharmacist, it is certainly possible. This article provides a framework to aid the diagnosis and appropriate management of hearing loss and tinnitus in the community pharmacy.

The questions pharmacists and their teams can ask patients presenting with hearing loss and tininitus are included in the Table. A patient may complain of a specific symptom, but by asking about any co-existing issues, the pharmacist will be able to determine the most likely cause and, therefore, the most suitable course of action.

| The patient’s complaint | Follow-up questions to ask | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| “I can’t hear properly” | “Does it affect one or both ears?” | Acute otitis media (inflammation of the middle ear) and ‘glue ear’ can affect one or both ears in children. In adults, both ears being affected may be a sign of age-related hearing loss; however, if only one ear is affected, further investigations may be required to exclude other causes, such as an acoustic neuroma (a benign growth on the hearing and balance nerve). |

| “Was the onset sudden or gradual?” | Gradual loss of hearing suggests age-related hearing loss. However, if a sudden sensorineural hearing loss occurs, patients should be seen urgently by an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist to assess whether oral steroids should be given to optimise recovery of hearing. | |

| “Is it progressive or fluctuating?” | Age-related hearing loss is gradual, whereas children with glue ear often have fluctuations in their hearing, with reduction associated with colds in the winter months. | |

| “I have this constant ringing in my ear” | “Does it affect one or both ears?” | Bilateral tinnitus is common, but if it only affects one ear, patients should be referred to an ENT specialist for an MRI scan to exclude acoustic neuroma. |

| “What is the nature of the ringing, does it buzz or pulsate?” | If the tinnitus is in time with the patient’s pulse, it may be of vascular origin and referral for assessment for vascular lesions is advised. | |

| Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[3] ,[4] | ||

Hearing loss

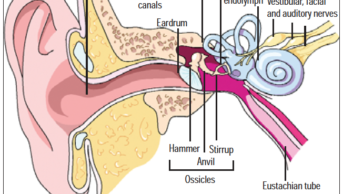

A common ear problem that patients of all ages may present with is hearing loss or deafness. Young children commonly present with fluctuating hearing loss, known as ‘glue ear’, which is caused when the middle ear — normally air-filled — becomes filled with fluid. This fluid tends to look like glue, hence the name.

Glue ear may be secondary to an acute otitis media (acute middle-ear infection) or a result of eustachian tube dysfunction. It has an incidence of 40% in children aged two years, reducing to 1.4% in those aged 11 years[5]

. Common symptoms accompanying temporary hearing loss in one or both ears may include:

- Earache or hyperacusis (sensitivity to noise);

- Clumsiness owing to disruption of the vestibular system causing impaired balance;

- Tinnitus.

Long-term glue ear can affect a child’s hearing and speech development, their concentration, behaviour and performance at school[5]

. These children are assessed by audiology and ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialists and they may be monitored, offered hearing aids or advised on surgery (i.e. the placement of ventilation tubes often referred to as ‘grommets’) depending on the level of hearing loss and its effect on the child, as well as the appearance of the eardrums[5]

.

Adults may also experience glue ear. This usually occurs after a cold and, although rare, it can be the presentation of a mass in the post-nasal space. As glue ear is less common in adult patients, they should be referred to their GP who can then refer them to the ENT specialist.

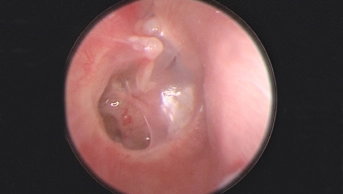

If, when a patient is asked to hum, they hear the sound loudest in their deaf ear, they have conductive hearing loss[6]

. Older people are more likely to present with progressive sensorineural hearing loss (i.e. hearing loss in which the root cause lies in the inner ear), the most common form of which is known as presbycusis. This hearing loss is known to affect half of adults by the age of 75 years and nearly all adults aged over 90 years[7]

.

Acute hearing loss or muffled hearing is often attributed to the build-up of wax in the ear canal. Wax may totally occlude the ear canal in patients:

- With narrow or hairy ear canals;

- Who have exostosis or osteomas (bony growths);

- Using cotton buds, which instead of cleaning the ears can result in wax impaction[3]

.

Management

Glue ear in children may be diagnosed by the GP via otoscopy, after which the child can be referred to the audiology/ENT department for a hearing test. This condition usually resolves spontaneously within three months; however, if the patient’s hearing loss persists after three months and the child is symptomatic, then temporary hearing aids or surgical intervention, such as grommets, may be required. A nose balloon (Otovent; Kestrel Medical) can be used in children from the age of three years to encourage air to pass from the back of the nose to the middle ear and help resolve the glue ear by equalising the pressure and allowing the fluid in the middle ear to drain naturally down the back of the throat[8]

. Pharmacists should be aware of how to use this device.

Patients with a recurrent build-up of wax may benefit from the use of water or oil-based ear drops, initially for three to five days to clear the wax, or once per week prophylactically[9]

. It should be noted that some ear drops contain arachis (peanut) oil, so it is essential that pharmacy staff check whether patients are allergic to peanuts before recommending such products[10]

.

A 2013 Cochrane review did not find any difference in the efficacy or side effects between water-based and oil-based ear drops[11]

. However, anecdotally, many ENT specialists find the use of sodium bicarbonate ear drops to be the most effective, perhaps as ear wax is water-soluble and the oil-based preparations have only a softening effect in in vitro studies.

Patients should be warned that the drops may cause transient hearing loss, discomfort, dizziness and skin irritation. Drops should not be advised in patients known to have a perforated eardrum, with a history of ear surgery (unless advised by the ENT specialist) or if an infection is present.

Although less commonly known, ear candling may still be requested by some patients. This should never be used in the management of ear wax removal and may result in serious injury[9]

.

Patients may need to have ear wax removed prior to having impressions for a hearing aid mould, to prevent feedback in hearing aid users or to enable visualisation of the eardrum to establish a diagnosis by the GP or ENT specialist.

Red flags and referrals

Patients presenting with sudden hearing loss in one ear as a sole symptom should be referred urgently to a GP. The cause may be sensorineural (i.e. caused by a lesion or disease of the inner ear or the auditory nerve) and oral steroids with or without antiviral medication may be beneficial[11],[12]

.

Ramsay-Hunt Syndrome (i.e. herpes zoster oticus) may be considered in patients presenting with all or some of the following symptoms:

- Ear pain;

- Crusting on the pinna;

- Hearing loss;

- Tinnitus;

- Facial nerve palsy (difficulty closing one eye, dry eye and altered taste);

- Vertigo (sensation of moving or spinning).

This will require an urgent GP referral for antiviral medication, either with or without oral steroids[11],[12]

.

Tinnitus

The sensation of hearing noises that are not caused by an external source, known as tinnitus, is associated with hearing loss in 90% of patients (although many patients are unaware of their hearing loss as it may be mild and of gradual onset)[13]

.

It may be described as ringing, buzzing, whooshing, humming, hissing, throbbing, music or singing, and patients may hear these sounds in one or both ears, or in their head[14]

. The noises can come and go or could be heard at all times.

Red flags and referral

Referral to a GP is advised when the tinnitus is unilateral, as this could be a symptom of an acoustic neuroma or if it is bilateral and causing significant distress to the patient[4]

.

Causes

A review of the person’s medication may be useful since their GP may wish to stop any medicines known to cause tinnitus. Although it is usually only reported in fewer than 1 in 1,000 people taking a medicine and may be dose-dependent (e.g. patients taking high-dose aspirin, quinine and loop diuretics [furosemide, bumetanide and ethacrynic acid])[14]

.

It is important to be aware that some antibiotics — including the aminoglycosides (gentamicin and neomycin), ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin — and chemotherapy agents — such as methotrexate and cisplatin — are known to cause or worsen tinnitus. Medicines used to treat hypertension (such as angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors), hypercholesterolaemia (such as atorvastatin), anxiolytics and antidepressants should also be reviewed as they can potentially cause tinnitus.

Although it is not always clear what causes tinnitus, it is often associated with damage to the inner ear[15]

. This can be caused by natural decline with ageing and medicine use, but may also be a result of:

- Exposure to sudden loud noises;

- Head injury;

- Anaemia, when blood circulates rapidly due to reduced red blood cell count;

- Paget’s disease, owing to normal bone renewal and repair cycle being disrupted;

- Thyroid disorders (such as hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism);

- Diabetes[15]

.

Management

If referral is not required, reassure the patient that tinnitus is common and usually improves with time and with habituation (whereby the conscious awareness of the tinnitus reduces with exposure), thereby reducing the impact of tinnitus on their life.

People are more aware of their tinnitus in quiet environments and often use background noise (music or radio) to reduce its intrusiveness. There are several mobile phone apps available for this purpose, including ReSound Relief (GN Hearing) and Starkey Relax (Starkey Hearing Technologies). These apps include a disclaimer indicating their use under the guidance of a specialist.

Pharmacy teams should also consider directing the patient to the British Tinnitus Association website (www.tinnitus.org.uk), which provides patient information on what tinnitus is, what can be done to manage it, how to prevent it and details on local support groups[14]

.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge the advice from Shahid Chowdhury and Nirali Sisodia, pharmacists at Kettering General Hospital, Northamptonshire

References

[1] Hannaford PC, Simpson JA, Bisset AF et al. The prevalence of ear, nose and throat problems in the community: results from a national cross-sectional postal survey in Scotland. Fam Pract 2005;22(3):227–233. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi004

[2] NHS England. Stay Well Pharmacy campaign. 2018. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/stay-well-pharmacy-campaign (accessed November 2019)

[3] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hearing loss in adults: assessment and management. NICE guideline [NG98]. 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng98 (accessed November 2019)

[4] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Scenario: management of tinnitus. 2017. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/tinnitus#!scenario (accessed November 2019)

[5] Richard AM. Otitis media with effusion. In Kerr AG, Adams DA & Cinnamond MJ. Scott Brown’s Otolaryngology: Paediatric Otolaryngology. 6th edn. London: Hodder Education Publishers; 1996

[6] Ahmed OH, Gallant SC, Ruiz R et al. Validity of the hum test, a simple and reliable alternative to the Weber test. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2018;127(6):402–405. doi: 10.1177/0003489418772860

[7] Davis AC. The prevalence of hearing impairment and reported hearing disability among adults in Great Britain. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18(4):911–917. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.4.911

[8] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Otovent nasal balloon for otitis media with effusion. Medtech innovation briefing [MIB59]. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib59 (accessed November 2019)

[9] Aaron K, Cooper TE, Warner L & Burton MJ. Ear drops for the removal of ear wax. 2018. Available at: https://www.cochrane.org/CD012171/ENT_ear-drops-removal-ear-wax (accessed November 2019)

[10] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Earwax. 2016. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/earwax (accessed November 2019)

[11] Wei BPC, Stathopoulos. Steroids for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. 2013. Available at: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003998.pub3/information (accessed November 2019)

[12] Awad Z, Huins C & Pothier D. Antivirals for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. 2012. Available at: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006987.pub2/full (accessed November 2019)

[13] Sanchez TG, Mak MP, Pedanlini MEB et al. Tinnitus and hearing evolution in normal hearing patients. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2005;9(3):220-227

[14] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Tinnitus. 2017. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/tinnitus (accessed November 2019)

[15] NHS Inform. Tinnitus. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/ears-nose-and-throat/tinnitus (accessed November 2019)