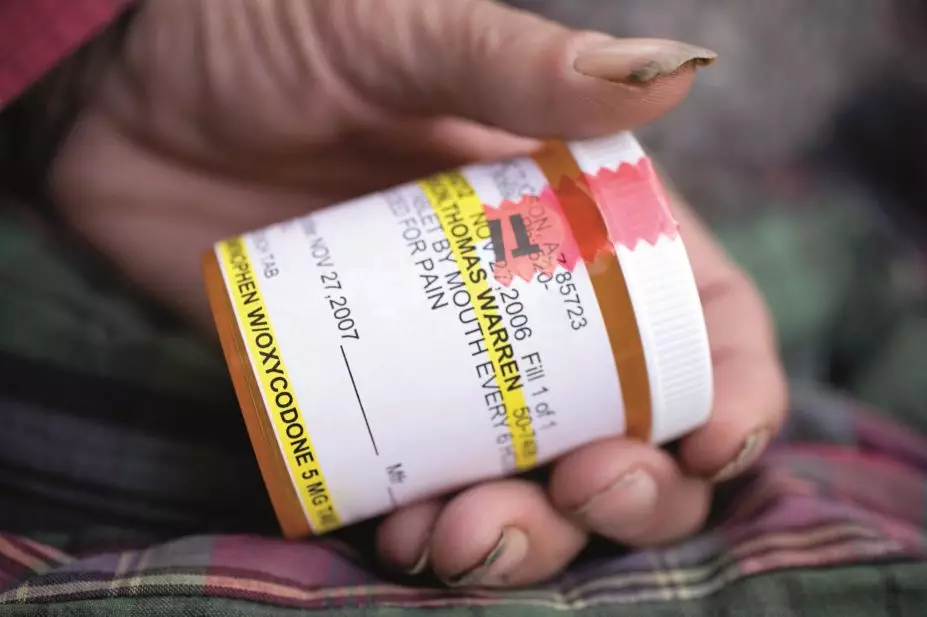

Jeff Smith / Alamy Stock Photo

In this article you will learn:

- How to recognise the challenges and address misconceptions when managing pain in patients with substance use disorders

- How to manage acute and chronic pain in patients with substance use disorders

- How to monitor the effectiveness and outcomes of treatments

Pain is one of the most commonly experienced symptoms in adults and is often described as acute or chronic. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage and expressed in terms of such damage”[1]

.

Acute pain usually results from an injury or surgical intervention, and will diminish and disappear as the injury recovers. It usually has a recent onset and is less than three months in duration (often only lasting for a few days). Acute pain can often be described as ‘useful’, acting as a warning system to prevent further damage. Acute pain is extremely prevalent, with 61% of patients reporting severe to moderate levels[2]

.

Chronic pain does not settle as the acute injury recovers and is characterised by a duration longer than three months, leading to prevention of normal functioning. Unlike acute pain, it is not ‘useful’ and is often difficult to manage. The prevalence rate for chronic pain has been reported at between 13.0% and 50.4% in the UK[3]

.

Little is known about chronic pain in patients with a substance use disorder, although a small number of international studies indicate a prevalence of 15–37%[4]

,[5]

,[6]

.

Access to pain medication is enshrined in international human rights law[7]

and it should not be denied to any patient. For patients with a current or past history of substance misuse, the challenge is balancing this right against the possibility of misuse, especially when prescribing opioids. Pharmacists can support hospitals in developing policies for the management of pain in this patient group. Community pharmacists are an essential part of the wider healthcare team supporting patients with advice on the management of pain presented in the pharmacy.

This article describes the challenges associated with treating and managing acute and chronic pain in patients presenting with a substance use disorder.

Pain pathophysiology

Pain is a complex process and is experienced through the pain pathway

[8]

. Pain is mediated through the initial receptor activation in a process termed transduction. The message is then relayed from the nociceptors to the central nervous system in the transmission process. Finally the message is interpreted in the higher centres of the brain as pain is experienced during perception. Modulation can reduce or enhance this perception and can occur through many points within the transmission process.

Multimodal prescribing is a concept that describes using various agents at different sites of the pain pathway to maximise pain management. Combinations of drugs with different mechanisms are often used to target different sites in this pathway to manage the pain. This allows lower-dose combinations to be used, which may also minimise the risk often seen with high doses of individual drugs.

Managing pain in patients with substance use disorders

A number of misconceptions need to be challenged when managing patients with substance use disorders[9]

. Maintenance opioid agonists do not provide adequate analgesia for the patient, as tolerance counterbalances any analgesic effect. In addition, two additional factors need to be considered. Firstly, methadone or buprenorphine given as a once daily dose, usually in the range of 60–120mg for methadone substitution therapy and 12–24mg for buprenorphine substitution therapy[10]

, does not provide an effective analgesic profile. For this to be achieved, the maintenance dose would need to be administered every six to eight hours[11]

,[12]

. Secondly, high doses of opioids can induce opioid-induced hyperalgesia. This complex presentation results from neuroplastic changes in the nervous system leading to increased pain sensitivity[13]

. In effect, tolerance leads to a decreased sensitivity to opioids, while opioid-induced hyperalgesia results in an increased sensitivity to pain resulting from opioid use. Detoxified and long-term abstinent patients have also been demonstrated to have increased pain thresholds in comparison to healthy controls[14]

. Tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia may co-exist, however some characteristic features associated with opioid-induced hyperalgesia exist (see ‘Features of opioid induced hyperalgesia’).

Features of opioid induced hyperalgesia

- Produces a typically diffuse pain;

- Pain is less defined in quality;

- Pain often extends to other areas of distribution from pre-existing pain;

- Presentation mimics opioid withdrawal;

- Pain is worsened by an increase in opioid dose.

No formal guidelines exist about management of these patients and treatments are not evidence-based. However, it has been proposed that reducing the opioid dose (increasing the dose of the opioid will result in an increased pain sensitivity), changing the opioid (opioid rotation) and/or optimising non-opioid analgesics, often in combination with a reduction in the opioid dose, may help to manage this increased pain sensitivity[1],[13]

.

The second misconception is that use of opioid analgesics will trigger a return to uncontrolled opioid use. Exposure to a former drug of choice can be a powerful trigger for relapse[16]

and a prior addiction to opioids elevates the risk of relapse to opioid addiction[17]

. However, the levels of elevated risk have not yet been defined and clinicians are aware that inadequate pain control may lead to relapse, as the patient may attempt to manage their pain through illicit drug use[18]

,[19]

. This complex inter-relationship supports the need for robust multidisciplinary management and care in this cohort of patients, ideally involving pain and addiction treatment specialists, as well as key workers, social workers and pharmacists.

Some clinicians believe that the addictive effects of opioid analgesics and maintenance opioids may increase the risk of respiratory depression, however, this is untrue because of the effects of tolerance. Some patients may consume multiple psychoactive agents that may impact on the safety of the patient (e.g. benzodiazepines and alcohol), so monitoring is still required.

On admission of a patient with a substance use disorder to hospital, clinicians should confirm the prescribed dose of a reported opioid substitute with the dispensing pharmacist and/or prescriber, who should also be informed of the patient’s admission to hospital. Patients on methadone who are not part of a supervised consumption scheme may not have been taking their full dose in the community, therefore care needs to be taken in the first few days of treatment in the hospital environment. In these cases, administration of the full dose could lead to over-sedation, unconsciousness and even respiratory depression if the full dose is administered[15]

.

Unfortunately, in some instances clinicians may judge that the pain complaint is a manifestation of drug seeking behaviour and the stigma associated with this is probably the greatest obstacle to managing pain in opioid-dependent individuals[20]

. This approach may also compromise the therapeutic relationship between the clinician and patient, however, this can be allayed through careful clinical assessment. By taking a comprehensive patient history and by involving a multidisciplinary team, including pharmacists, it is possible to implement an individualised care plan with appropriate monitoring.

Pain management: acute pain

It should be recognised that some patients with previous opioid dependence problems may not want their pain treated with opioids. The abstinence programme of organisations, such as Narcotics Anonymous, presents a dilemma for both the patient and clinician. In these circumstances, even though the risk of relapse is considered low, an individualised non-opioid care plan should be established that includes the patient’s views.

For patients with a current self-reported history of opioid dependence not currently prescribed opioid substitution treatment, a robust clinical assessment with appropriate opioid screening (see ‘Common mechanisms for opioid screening in the hospital setting’) should be undertaken and opioid substitution treatment commenced according to the local hospital policy[15]

. This meets the primary objective of avoiding withdrawal and establishes a level of stability, allowing a pain management plan to be initiated. The stabilisation dose, which will vary depending on the tolerance of the patient, may also be divided during the day to support a better analgesic response. Usually a starting dose of 10–20mg is used and opioid and non-opioid analgesics can be administered concurrently in both scenarios and titrated against the analgesic response, with careful clinical monitoring of opioid adverse effects, especially over-sedation.

Common mechanisms for opioid screening in the hospital setting

- Urine Drug Screen (UDS): Regarded as the most reliable and cost-effective screen and used by the majority of drug treatment clinics in the UK. Window of detection for drugs is up to three days.

- Oral Fluid Test (OFT): A less invasive method that allows the patient to be observed while the test is undertaken. Patient should not eat or drink for at least ten minutes before taking the test to avoid contamination of the sample. Generally more expensive to administer than UDS and a shorter window of detection (up to 24 hours).

In the community setting, on account of the limited monitoring available, a more conservative management approach needs to be adopted for acute pain. Patients who are not undergoing treatment for substance misuse should be assessed by a clinician with expertise in this area, or referred to the local drug and alcohol service to enable stabilisation. One problem is that these assessments are often only available after the episode of acute pain has been evident for a period of time or even after it has subsided. In these cases, use of opioids for pain management cannot be excluded for moderate to severe pain. The British National Formulary (BNF) supports prescribing opioids for patients who are dependent on them or have a history of drug dependence if there is a ‘clinical need’[21]

. Nevertheless, prescribing should be preceded by a comprehensive patient assessment covering a number of factors (see ‘Elements of a comprehensive patient assessment’) and, if opioid prescribing is undertaken, a risk-benefit analysis should be performed. Practical steps to prescribing should be adopted and the pharmacist is best placed to provide this advice.

Clinicians should only prescribe if they have the necessary skills and competencies and involve a wider multidisciplinary team (e.g. pain and addiction clinicians). Multimodal prescribing may support an opioid sparing strategy but clinicians should be mindful that non-opioids may also still be misused[24]

.

Elements of a comprehensive patient assessment

- Pain and coping: Assess location, character, pain type using validated tools, assessing response to previous treatments and patients’ goals and expectations.

- Collateral information: Findings from other clinicians and healthcare professionals and investigation of previous medical records.

- Function: What is the effect of the pain on the function of the patient?

- Substance use history and risk for addiction: In addition to an assessment of current (including screening) and past use, this should also assess current recovery networks; clinicians may consider use of screening tools such as the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) at this point, to risk assess potential for misuse of the medication, but this should not limit the prescribing if clinically appropriate.

- Co-occurring conditions and disorders (physical and mental).

- Physical examination: Both for assessment of pain condition and for signs of current substance misuse.

- Current mental state assessment

For patients currently prescribed buprenorphine, an alternative treatment approach needs to be adopted, especially if the patient is taking a dose of 12–24mg a day, which should result in a total blockade of µ-opioid receptors. However, on some occasions, µ-opioid receptor blockade may not be complete. For patients undergoing elective surgery, an analgesic response has been observed when administering short-acting opioids sometimes at a higher dose than usual[15],[23]

but this should be given under specialist pain management supervision and closely monitored.

From a pharmacological standpoint, most patients should experience little analgesia from opioids when prescribed a “blocking dose” of buprenorphine (i.e. above 12mg). For example, a 16mg dose of buprenorphine has been shown to reduce µ-opioid receptor availability by 85–92% compared with 41% for 2mg buprenorphine[24]

. Therefore, alternative non-opioid multimodal approaches such as paracetamol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and adjuvant medications (tricyclic antidepressants) will be required. If the patient wants to remain on buprenorphine, this may also be given in a six to eight-hourly dosing regime to improve the pain management response.

Short-acting opioid analgesics can be prescribed for acute pain similar to that for patients receiving methadone, if the patient is on a dose less than 12mg, although partial blockade from the buprenorphine may result in a limited effect. Alternatively, and only after seeking specialist advice, a patient can be transferred to methadone treatment for pain, as described above. A more conservative approach could be adopted in the community setting and a regime of high-dose short-acting opioids should not be encouraged.

Pain management: chronic pain

Management of chronic pain presents a challenge because of the potential long-term nature of the prescribing intervention. Tools developed in the United States, such as the ORT tool[25]

, may support the clinician in assessing the risk of a patient misusing psychoactive medication[26]

. However, when using these tools the clinician must be mindful that they have not been validated in the UK and they should not be used to “deny therapy for those with a pain syndrome… but can guide the prescriber regarding the degree to which therapy should be supervised”[25]

.

A comprehensive assessment involving both pain, addiction clinicians and other members of the multidisciplinary team, including pharmacists, remains the essential element of the management of chronic pain. The expectations and goals of treatment, the need for frequent assessments, and acceptable and non-acceptable behaviour should be communicated to the patient. Some services may choose to support this with a treatment contract[27]

.

Practical steps for prescribing also need to be adopted. Smaller quantities initiated through a more frequent pick-up regime (e.g. daily or three times a week collection) with regular reviews (e.g. weekly or every two weeks) need to be established, although this may be subject to change based on the clinical presentation of the patient. Very high doses should be avoided. The British Pain Society recommend that if patients do not experience relief of pain when doses are titrated to between 120–180mg morphine equivalent per 24 hours, then referral to a specialist in pain medicine is recommended[28]

. Long-acting opioid formulations, such as Zomorph (slow release oral morphine) and Oxycontin (slow release oxycodone), should be favoured for chronic pain over frequent short-acting formulations, such as Oramorph oral solution (immediate release morphine) or Oxynorm (immediate release oxycodone), which can produce maximal stimulation of the reward pathway[29]

. Reviews should be used to identify any “red flags” that may indicate instability and inappropriate use of the prescription medication. Reviews should also be used as a guide for the ongoing individualised care plan, rather than a punitive tool allowing the reduction or cessation of prescribing, except in exceptional circumstances where the safety of the patient or other individuals may be compromised (e.g. significant “on-top” illicit drug use).

These may include:

- Presenting intoxicated, impaired or dishevelled;

- Early requests for prescriptions, especially if frequent;

- ‘Lost’ prescriptions;

- Concurrent misuse of related illicit drugs;

- No interest in the diagnosis;

- Failure to keep appointments or refusal of further tests or to see other practitioners for consultations;

- Drug stockpiling;

- Requesting specific drugs;

- Selling prescription drugs.

Monitoring effectiveness of treatment

Monitoring outcomes is an essential component of a robust management plan for all patients taking opioids. A useful mnemonic, the “four A’s”[30]

can be employed here. It provides a simple structure to the review process and comprises the following elements:

- Analgesia: this involves an assessment of the pain relief provided through the management plan using a validated tool. A variety of tools are available, including the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)[31]

and comprehensive McGill Pain Assessment Tool[32]

, which is also available as a shortened version. A baseline figure is an essential component of this plan. - Activities of daily living: functioning can be assessed by simply noting the patient’s abilities in differing areas (e.g. social relations, work, walking ability) against the baseline measurement. Occupational therapists may help with these assessments.

- Adverse effects: opioid side effects should be noted and the impact on the patient’s quality of life assessed.

- Aberrant drug-related behaviour: this assessment could be led by patient contracts, simple assessments of the “red-flags”.

Graham Parsons BPharm(Hons), PGDip (Comm Pharm), IPresc MRPharmS is a pharmacist with a special interest in substance misuse at Devon Clinical Commissioning Group.

Acknowledgement: The author would like to acknowledge the work of Dr Rhys Ponton is developing the themes for this paper and for his work in reviewing the article prior to publication.

References

[1] International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). IASP Taxonomy (2015). Available at: http://www.iasp-pain.org/Taxonomy#Pain (accessed August 2015).

[2] McCaffery M & Pasero C. Pain — Clinical Manual (1999). Mosby; 2nd edition.

[3] Seymour M & Patterson S. Estimating the prevalence of chronic pain in a given geographical area. Journal of Observational Pain Medicine 2014;1(3). Available at: http://www.joopm.com/index.php?journal=joopm&page=article&op=view&path%5B%5D=46 (accessed October 2015).

[4] Rosenblum A, Joseph H, Fong C et al. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain among chemically dependent patients in methadone maintenance and residential treatment facilities. J Amer Med Assoc 2003;289:2370–2378. doi:10.1001/jama.289.18.2370

[5] Chelminski PR, Ives TJ, Felix KM et al. A primary care, multi-disciplinary disease management program for opioid-treated patients with chronic non-cancer pain and a high burden of psychiatric comorbidity. BMC Health Services Research. 2005;5:3. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-5-3

[6] Ballantyne JC & LaForge SK. Opioid dependence and addiction during opioid treatment of chronic pain. Pain 2007;129(3):235–255. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.028

[7] Lohman D, Schleifer R & Amon J. Access to pain treatment as a human right. BMC Medicine 2010;8:8:1741–7015. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-8

[8] Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education. Pain: treatment and management (2015). Available at: https://www.cppe.ac.uk/programmes/l/paind-p-01/ (accessed October 2015).

[9] Alford DP, Compton P & Samet JH. Acute pain management for patients receiving maintenance methadone or buprenorphine therapy. Ann Intern Med 2006;144(2):127–134. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00010

[10] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Opioid dependence: Scenario: Continuing maintenance therapy (2015). Available at: http://cks.nice.org.uk/opioid-dependence#!scenario:3 (accessed October 2015).

[11] Summary of Product Characteristics. (2015) Methadone Hydrochloride DTF1mg/1ml Oral Solution. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/10721 (accessed September 2015).

[12] Summary of Product Characteristics. (2015) Temgesic 400 microgram Sublingual tablets. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/1877 (accessed September 2015).

[13] Lee M, Silverman S, Hansen H et al. A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician 2011;14(2):145–161. Available at: http://www.painphysicianjournal.com/current/pdf?article=MTQ0Ng%3D%3D&journal=60 (accessed October 2015).

[14] Liebmann PM, Lehofer M, Moser M et al. Persistent analgesia in former opiate addicts is resistant to blockade of endogenous opioids. Biological Psychiatry 1997;42:962–964. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00337-5

[15] Prosser M, Steinfeld M, Cohen LJ et al. Abnormal heat and pain perception in remitted heroin dependence months after detoxification from methadone-maintenance. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2008;95(3):237–244. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.012

[16] Daley DC, Marlatt GA & Spotts CE. Relapse prevention: Clinical models and intervention strategies. In Graham AW, Schultz TK, Mayo-Smith MF, Ries RK & Wilford BB (Eds.), Principles of addiction medicine (3rd ed., pp. 467–485). Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine.

[17] Turk DC, Swanson KS & Gatchel RJ. Predicting opioid misuse by chronic pain patients: a systematic review and literature synthesis. Clin J Pain 2008;24(6):497–508. doi:10.1097/ajp.0b013e31816b1070

[18] Wasan AD, Correll DJ, Kissin I et al. Iatrogenic addiction in patients treated for acute or subacute pain: a systematic review. Journal of Opioid Management 2006;2:16–22. PMID: 17319113

[19] Stromer W, Michaeli K & Sandner-Kiesling A. Perioperative pain therapy in opioid abuse. European Journal of Anaesthesiology 2013;30:55–64. doi:10.1097/eja.0b013e32835b822b

[20] Bell J, Reed K, Gross S et al. The management of pain in people with a past or current history of addiction (2013). Available at: http://www.actiononaddiction.org.uk/Documents/The-Management-of-Pain-in-People-with-a-Past-or-Cu.aspx (accessed September 2015).

[21] British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2015). Opioid analgesics (4.7.2) British National Formulary (BNF) 68;280.

[22] Royal College of General Practitioners. (2013) Prescription and over-the-counter medicines misuse and dependence: Factsheet 1 – The Problem. Available at: http://www.smmgp.org.uk/download/guidance/guidance021.pdf (accessed September 2015).

[23] Alford DP, Compton P & Samet JH. Acute pain management for patients receiving maintenance methadone or buprenorphine therapy. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:127–134. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00010

[24] Greenwald MK, Johanson C-E, Moody DE et al. Effects of buprenorphine maintenance dose on µ-opioid receptor availability, plasma concentrations, and antagonist blockade in heroin-dependent volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003;28:2000–2009. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300251

[25] Cathy Stannard. All Party Parliamentary Group on Drug Misuse Inquiry Response on behalf of the British Pain Society. 2007.

[26] The American Academy of Pain Medicine. Tools/Forms. 2015. Available at: http://www.painmed.org/SOPResources/ClinicalTools/tools-forms/ (accessed August 2015).

[27] Chronic Pain Scotland. Treatment contract for the use of an opioid medicine (morphine-like painkiller) for the management of chronic pain. 2015. Available at: http://chronicpainscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Treatment-Contract-for-the-use-of-an-opioid-medicine1.pdf (accessed August 2015)

[28] British Pain Society. Opioids for persistent pain: Good practice. 2010.

[29] Samaha A & Robinson T. Why does the rapid delivery of drugs to the brain promote addiction? Trends in Pharmacological Science 2005;26:82–87. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2004.12.007

[30] Passik S, Kirsh KL, Whitcomb L et al. A new tool to assess and document pain outcomes in chronic pain patients receiving opioid therapy. Clinical Therapeutics 2004;26(4):552–561. doi:10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90057-4

[31] Crichton N. Information Point: Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2001;10:697–706. Available at: http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/specialarticles/jcn_10_706.pdf (accessed September 2015).

[32] Flaherty SA. Pain measurement tools for clinical practice and research. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Anaesthetics 1996;64(2):133–140. PMID: 9095685