Shutterstock.com

A stoma (sometimes referred to as an ostomy) is an opening made during surgery where the colon, ileum or bladder is diverted through the abdominal wall, allowing faeces or urine to be collected in an external pouch. Stomas do not have any nerve endings; are pink or red, warm and moist in nature; resemble the colour of gums; and are round or oval[1],[2],[3],[4]

. The size and shape of a stoma can vary in size and, depending on the type of stoma, mucus may be secreted. Stomas may initially be swollen after surgery and may take between six to eight weeks to reduce in size[1],[2],[4]

.

More than 13,500 people in the UK undergo stoma surgery each year as a result of a medical condition, including bowel, bladder or prostate cancer; inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis); diverticulitis; or trauma to the abdomen[1],[2],[4]

.

Although the use of a stoma can help patients live healthy normal lives, it may have an impact on their diet and medicines[5],[6]

. In addition, many patients have irritation around the stoma site[7],[8]

. Pharmacists require a basic knowledge of stomas and the care needed to help patients manage symptoms and medicines treatment, and know when to signpost to the relevant healthcare professional.

Types of stoma

A temporary stoma has the possibility of being reversed with another operation and is created for a minimum of six weeks, with the intention that bowel function resumes normally[9],[10],[11]

. A permanent stoma is created when there is not enough bowel to create a continuous pathway from the healthy bowel to the anus, or if the bladder needs to be bypassed or removed (known as a urostomy)[9],[10],[11]

.

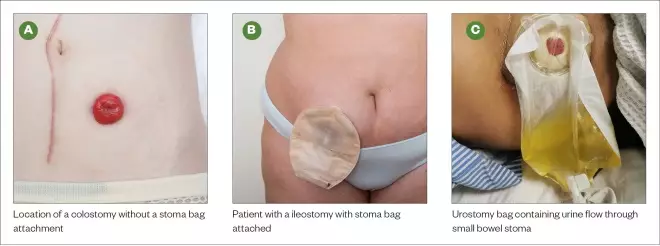

A colostomy is a surgical procedure created when an opening in the large bowel (i.e. the colon) is brought to the surface of the abdomen. This opening is usually on the left side of the abdomen and the output of faeces from the stoma is usually firm and well formed (see Photoguide A)[1]

.

An ileostomy is an opening in the small intestine (particularly the ileum) brought out to the surface of the abdomen, bypassing or removing the large intestine to create the stoma. This opening is normally on the right-hand side of the abdomen. The output of this stoma tends to be looser than a colostomy (see Photoguide B)[1]

.

A urostomy is formed when a short piece of the small intestine, known as an ‘ileal conduit’, is attached to the ureters, allowing urine to pass through an opening in the abdomen. This passageway bypasses the bladder, and in certain cases the bladder may be removed completely (see Photoguide C)[1]

.

Photoguide: Example of stomas types and location

Source: Shutterstock.com

A: location of a colostomy without a stoma bag attachment; B: patient with ileostomy with stoma bag attached; C: Urostomy bag containing uring flow through small bowel stoma

After stoma surgery

After surgery, the stoma is initially swollen and can take between six to eight weeks to heal and reduce in size[1],[2],[4]

. A bag, sometimes referred to as a pouch, is fitted around the stoma for contents to be drained into. With both a colostomy and ileostomy, it can take a few days for the stoma to start functioning. It is quite common for wind to pass through the stoma first as the bowel has been inactive. However, within two to three days, a motion should pass, which may, at first, be of a liquid consistency, but should gradually become more solid and formed[12],[13]

. In the case of a urostomy, the stoma generally starts working immediately[13]

.

The output from the stoma varies in volume, depending on how much the patient consumes. For example, in ileostomy patients, this can be around 400–800mL in a 24-hour period[14]

. A high-output stoma is one that produces more than 1–1.5L per day[15]

. A high-output stoma can occur for various reasons, such as:

- A newly formed stoma;

- The bowel being damaged or affected by severe disease, such as recurrent Crohn’s disease;

- Infection;

- Medication (e.g. suddenly stopping steroids)[14],[15],[16]

.

Before a patient is discharged from hospital, a stoma nurse will explain to the patient how to change a stoma bag (video demonstrations are available from Macmillan Cancer Support)[17]

. Information will also be provided on diet (e.g. maintaining weight, drinking adequately and avoiding wind-producing foods [for example cabbage, beans, spicy foods]); returning to work; and complications that may arise with a stoma[5],[18],[19]

. Importantly, they will answer any queries the patient may have.

When a patient is discharged from hospital, they are given some supplies to take home and are typically given prescriptions for further supplies. The stoma nurse will also discuss with the patient how to obtain stoma supplies. Patients with a permanent stoma will be exempt from prescription charges and will need to apply for a prescription exemption certificate. However, those with a temporary stoma will have to pay for their prescriptions[7]

.

Cleaning and stoma care

The patient should empty the contents of the stoma bag into the toilet and the used bag should be sealed into a disposal bag, along with any wipes used. This can then be discarded into normal domestic waste. Some local authorities offer a collection service for clinical waste, which they provide a yellow bag for and usually collect weekly. The patient will need to contact their local council to enquire whether the service is offered in the area in which they live[12],[20],[21]

.

Maintaining good skin care, particularly around the stoma (i.e. the peristomal skin), is crucial. Irritation or damage to this skin can increase the risk of leakage or skin problems, such as dermatitis[22],[23],[24]

. In addition, the area around the stoma is at risk of damage, for example:

- Ulcers — may be owing to ill-fitting stoma bags, so the patient should check their stoma, template and surrounding skin regularly;

- Folliculitis — inflammation of the hair follicles;

- Bleeding — on cleaning, patients may notice a small amount of bleeding; however, if blood is in the bag, they should speak to their stoma care nurse or GP[18]

.

Pharmacists should advise patients to care for their skin daily by keeping it clean; only using warm water to clean the area; avoiding soaps and wipes (which can cause skin soreness); and keeping the area moisturised. There are a range of cleaning agents, protective creams, lotions, deodorants and sealants that are suitable for patients with stomas[11]

. If the patient still has sore skin or requires further information, advise them to contact their stoma care nurse[4],[22]

.

Stoma bags

Each type of stoma will have its own bag as an output (e.g. closed, drainable, two-piece system and one-piece system). The choice of bag will depend on different factors including:

- How frequently the bag needs to be changed;

- Type of output;

- How well it can adhere to skin;

- Size (e.g. some systems are bulky and rigid);

- Comfort requirement (e.g. clips or fastenings can be uncomfortable);

- How easy it is to empty;

- Need for a flushable bag[25],[26]

.

Pharmaceutical care

Pharmacists should be aware of the pharmaceutical care required by some patients with stomas, including the common medicines and therapies used to manage their conditions, as well as medicines that the patient may use that can cause problems for those with stomas.

Analgesics

For stoma patients who are experiencing pain and require a non-opioid analgesic, paracetamol is usually suitable. As with all patients, opioid analgesics can cause constipation and should be used with caution. If anti-inflammatory analgesics are being used, faecal output should be monitored for traces of blood because of the potential side effect of increased bleeding[2],[11],[17]

.

Antimotility drugs

Loperamide and codeine reduce intestinal motility, allowing more water to be absorbed, causing the thickening of stools and hence reducing stoma output[11],[27],[28]

. Loperamide is usually preferred over opiates as it is not sedative or addictive, and does not cause fat malabsorption[11],[15]

. In patients with a short bowel, the enterohepatic circulation is severely disrupted and loperamide can pass through[11],[15]

. Higher doses of loperamide may be needed in instances such as this and for patients with a high-output stoma, but such use is unlicensed and usually initiated by hospital consultants[14],[29]

. Specialist centres in the UK typically use a maximum daily dose of 64mg, but in resistant cases daily doses can be as high as 96mg[29]

. Loperamide is given four times per day to reduce gut motility[11],[16]

.

In 2017, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency published a safety alert on high-dose loperamide and the reports of serious cardiac effects, such as QT prolongation, torsades de pointes and cardiac arrest. Although misuse has not been reported in stoma patients using high-dose loperamide, it is advised to be used with caution as patients may experience electrolyte disturbances[29],[30]

. In response, the British Intestinal Failure Alliance recommended continuing the use of high-dose loperamide in patients with intestinal failure as the risk of not treating the high-output stoma/fistula was greater than the risk of loperamide causing cardiac arrhythmias. They also recommended performing an electrocardiogram in all patients with a high-output stoma before initiation of a total daily dose below 80mg loperamide[29],[31]

.

Codeine can be added to loperamide if response on its own is inadequate[11],[15]

. The usual dose of codeine phosphate to further reduce stoma output is between 30–60mg, four times per day (maximum of 240mg daily)[14],[32]

. Loperamide and codeine should ideally be taken 30–60 minutes before food and bedtime[14],[16]

.

Antisecretory drugs

Patients with a stoma may be put on medication to reduce gastric acid secretion, which reduces stoma output. The most common drug classes used for this purpose are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs); H2-receptor antagonists; or somatostatin analogues. Omeprazole, used in high-output stoma patients, is usually taken orally as 40mg once per day or intravenously twice per day. Because of the side effects of omeprazole (such as hypomagnesaemia, osteoporosis and possibly cardiac arrhythmias), it is not advisable for continued therapy and it should be stopped if there is no effect. Octreotide, a somatostatin, 50 micrograms twice per day, is as effective as other antisecretory medication and is equivalent to omeprazole in reducing stoma output. It is, however, rarely used owing to it being delivered via a painful injection; causing potential gallstone formation; and inhibiting bowel growth hormones[15],[33]

.

Fluids

Hypotonic fluids taken orally by patients with a high-output stoma are not absorbed and will pass through into the stoma bag. Large sodium losses into the stoma can lead to dehydration[15],[33]

. It is therefore important for patients to restrict oral hypotonic fluids, such as squash and tea, to 0.5–1L in 24 hours[14],[32]

. They should instead replace these with oral rehydration solutions, which are more easily absorbed and prevent sodium loss: two examples of these solutions are St Mark’s solution and double strength Dioralyte (Sanofi; see Box)[14],[33],[34],[35]

.

Box: Oral rehydration solutions to maintain adequate fluids

It is essential to maintain adequate hydration, even with a high-output stoma. However, it is also essential to ensure adequate salt intake (as this is likely to pass into the stoma bag). This helps the body absorb fluid and keep it hydrated. Simple measures include adding an extra teaspoon of salt into the diet (unless contraindicated by another condition) and drinking oral rehydration solutions, for example:

- St. Mark’s solution — this consists of 20g (six level 5mL spoonfuls) of glucose, 2.5g (one heaped 2.5mL spoonful) of sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) and 3.5g (one level 5mL spoonful) of sodium chloride (salt). The ingredients should be dissolved in 1L of cold tap water, stored either at room temperature or in a fridge, and should be sipped throughout the day. These ingredients can be bought from community pharmacies, supermarkets or obtained from a prescription by the GP. It is often cheaper to purchase all ingredients than pay a single prescription charge. If, however, this solution is on an NHS prescription, the constituents should be prescribed individually. This ensures that the solution is reconstituted every day by the patient. It is also important to highlight that the solution should be discarded 24 hours after mixing. The solution may taste bitter, which can be minimised by adding a small quantity of fruit juice or cordial to the mixture, before making up to 1L.

- Double-strength Dioralyte (Sanofi) — this can be used as an alternative to St. Mark’s solution. It consists of dissolving ten sachets of Dioralyte in 1L of water, and drinking throughout the day, or dissolving two sachets in 200mL of water and drinking five times per day. Either way will equate to the patient consuming 1L of double strength Dioralyte in 24 hours. As each litre of this solution contains 40mmol potassium, this should be avoided in patients with renal impairment or hyperkalaemia[14],[33],[34],[35]

.

Antacids

These products contain magnesium salts, which may cause diarrhoea; aluminium salts, which may cause constipation; and calcium salts, which may cause calcium stones. All can affect stoma output and should be avoided when possible[11],[28],[36]

.

Digoxin

Stoma patients taking digoxin are susceptible to hypokalaemia as a result of depletion of fluid and sodium. Patients on digoxin should be monitored closely, and it may be advisable to initiate potassium supplements or a potassium-sparing diuretic with monitoring for early signs of toxicity[11],[28]

.

Diuretics

These can cause electrolyte imbalance and dehydration in stoma patients. Caution is required with ileostomy and urostomy patients, as they can become excessively dehydrated and potassium depletion can easily arise. When required, potassium-sparing diuretics are advisable[11],[28],[36]

.

Iron preparations

These can cause diarrhoea, constipation and sore skin in stoma patients. If iron is required in these patients, an intramuscular injection should be administered. In addition, modified-release preparations should be avoided[11],[28]

.

Laxatives

These should be avoided in patients with an ileostomy as they may cause rapid loss of water and electrolytes.

For colostomy patients, who may have constipation, it is advised for them to first try to increase fluid intake and dietary fibre. However, if this has little to no effect, a bulk-forming laxative (e.g. ispaghula husk) can be used. If this too has little effect, a small dose of a stimulant laxative, such as senna, can be tried. However, this should be used with caution.

Medicines that have diarrhoea as a side effect (e.g. antibiotics and metformin) should be used with caution[11]

. The excipient sorbitol (usually in sugar-free preparations) should be avoided in stoma patients because of its laxative properties)[11],[15]

.

General pharmacotherapy considerations

Medication-related issues can arise depending on the type of stoma the patient has and the medicines they are taking. The nature of the medication should therefore be carefully considered. For example, enteric-coated and modified-release preparations of medicines should be avoided, especially in patients with an ileostomy, as they may not release enough of its active ingredient and their benefit is therefore questionable[2],[11],[36]

. In patients with an ileostomy, uncoated tablets or liquid preparations are the preferred formulation to improve absorption[36]

.

Patients who have had an ileostomy may have low levels of vitamin B12. This is owing to the removal of the part of the intestine responsible for absorbing vitamin B12 in food. A deficiency in vitamin B12 can lead to vitamin B12 anaemia, also known as pernicious anaemia. If ileostomy patients present with symptoms, such as cognitive changes, unexplained fatigue, lethargy, dyspnoea, indigestion, palpitations, headache, tinnitus, visual disturbance or loss of appetite, it is important for the patient to speak to their GP. If this diagnosis is confirmed, the treatment includes vitamin B12 supplementation, in the form of injections or tablets[37],[38]

.

About the author

Meera Nadesalingam is an independent prescriber and locum pharmacist at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

References

[1] Colostomy UK. What is a stoma? 2019. Available at: http://www.colostomyuk.org/information/what-is-a-stoma/ (accessed July 2020)

[2] Bupa. Stoma care. 2020. Available at: https://www.bupa.co.uk/health-information/digestive-gut-health/stoma-care (accessed July 2020)

[3] American Cancer Society. What is an ileostomy? 2019. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/treatment-types/surgery/ostomies/ileostomy/what-is-ileostomy.html (accessed July 2020)

[4] Stomawise. What is a stoma? 2010. Available at: http://www.stomawise.co.uk/types-of-stoma/overview (accessed July 2020)

[5] Salts Healthcare. Diet and hydration advice. 2018. Available at: https://www.salts.co.uk/en-gb/your-stoma/living-with-a-stoma/dietary-nutritional-advice (accessed July 2020)

[6] Salts Healthcare. Medical advice. 2018. Available at: https://www.salts.co.uk/en-gb/your-stoma/living-with-a-stoma/medical-advice (accessed July 2020)

[7] Lyon C, Smith A, Griffiths C & Beck M. The spectrum of skin disorders in abdominal stoma patients. Br J Dermatol 2000;143(6):1248–1260. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03896.x

[8] Oakley A. Skin problems from stomas. DermNet NZ. 2006. Available at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/skin-problems-from-stomas/ (accessed July 2020)

[9] Bowel Cancer UK. Stomas. 2019. Available at: https://www.bowelcanceruk.org.uk/about-bowel-cancer/treatment/surgery/stomas/ (accessed July 2020)

[10] North Bristol NHS trust. Reversal of stoma (ileostomy or colostomy). 2019. Available at: https://www.nbt.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/attachments/Reversal%20of%20Stoma_NBT002926.pdf (accessed July 2020)

[11] Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary online. 2020. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/stoma-care.html (accessed July 2020)

[12] Colostomy UK. Living with a stoma. 2019. Available at: http://www.colostomyuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Living-with-a-stoma.pdf (accessed July 2020)

[13] ColoplastCare. When will the stoma begin to work? 2018. Available at: https://www.coloplastcare.com/en-AU/ostomy/the-basics/before-surgery/b2.7-when-will-the-stoma-begin-to-work/ (accessed July 2020)

[14] London North West Healthcare NHS Trust. Eating and drinking when you have a high stoma output. 2014. Available at: http://www.stmarkshospital.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/High-output-stoma-2014.pdf (accessed July 2020)

[15] Nightingale J & Woodward JM. Guidelines for management of patients with a short bowel. Gut 2006;55(Suppl 4):iv1–iv12. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.091108

[16] University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust. Managing with a high output stoma. 2011. Available at: https://www.leicestershospitals.nhs.uk/EasysiteWeb/getresource.axd?AssetID=33945&servicetype=Attachment. (accessed July 2020)

[17] Macmillan Cancer Support. Caring for a stoma. 2016. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WXDI21j9tAc (accessed July 2020)

[18] Salts Healthcare. Problems you may experience with a stoma. 2018. Available at: https://www.salts.co.uk/en-gb/your-stoma/living-with-a-stoma/problems-you-may-experience (accessed July 2020)

[19] Salts Healthcare. Returning to work. 2019. Available at: https://www.saltsmedilink.co.uk/Support-and-Advice/Ostomy/working-with-a-stoma (accessed July 2020)

[20] CliniMed. How do I dispose of my stoma bag? 2020. Available at: https://www.clinimed.co.uk/stoma-care/faqs/how-do-i-dispose-of-my-stoma-bag (accessed July 2020)

[21] Stomawise. Clinical waste. 2011. Available at: http://www.stomawise.co.uk/lifestyle/clinical-waste (accessed July 2020)

[22] Dansac. Caring for the skin around your stoma. 2018. Available at: https://www.dansac.com/en-gb/livingwithastoma/healthyskinaroundyourstoma/caringfortheskinaroundyourstoma (accessed July 2020)

[23] Colostomy UK. Sore skin/leakage. 2019. Available at: http://www.colostomyuk.org/information/stoma-problems/sore-skinleakage/ (accessed July 2020)

[24] Stomawise. Types of stomal skin problems. 2018. Available at: http://www.stomawise.co.uk/types-of-stoma/skin-conditions (accessed July 2020)

[25] Colostomy UK. Which bag? 2017. Available at: http://www.colostomyuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/which-bag-table.pdf (accessed July 2020)

[26] Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust. Walsall joint stoma prescribing guidelines 2019. 2019. Available at: https://walsallccg.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/Walsall-Joint-Stoma-Prescribing-Guidelines-2019-Final.pdf (accessed July 2020)

[27] Medlin S. High-output stomas. 2016. Available at: http://www.colostomyuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/HighOutputStomas.pdf (accessed July 2020)

[28] Birmingham, Sandwell, Solihull and environs APC Formulary. Stoma toolkit adults. 2018. Available at: http://www.birminghamandsurroundsformulary.nhs.uk/docs/acg/Stoma%20Toolkit%20Adult%202018.pdf?uid=588777494&uid2=201832393617227&UNLID=658672654202078161622 (accessed July 2020)

[29] Specialist Pharmacy Service. Can high dose loperamide be used to reduce stoma output? 2018. Available at: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/can-high-dose-loperamide-be-used-to-reduce-stoma-output/ (accessed July 2020)

[30] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Loperamide (Imodium): reports of serious cardiac adverse reactions with high doses of loperamide associated with abuse or misuse. 2017. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/loperamide-imodium-reports-of-serious-cardiac-adverse-reactions-with-high-doses-of-loperamide-associated-with-abuse-or-misuse (accessed July 2020)

[31] British Intestinal Failure Alliance. British Intestinal Failure Alliance (BIFA) position statement: the use of high dose loperamide in patients with intestinal failure. 2018. Available at: https://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/bifa/position-statements/use-of-loperamide-in-patients-with-intestinal-failure.pdf (accessed July 2020)

[32] Nightingale J & the British Intestinal Failure Alliance committee. Top tips for managing a high-output stoma or fistula. 2018. Available at: https://www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/bifa/bifa-top-tips-series-1.pdf (accessed July 2020)

[33] Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Managing your high-output stoma — a guide for patients. 2018. Available at: https://yeovilhospital.co.uk/patients-visitors/https-yeovilhospital-co-uk-page-id27757/managing-your-high-output-stoma-a-guide-for-patients/ (accessed July 2020)

[34] Doncaster and Bassetlaw Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. High-output stoma policy. 2018. Available at: https://www.dbth.nhs.uk/document/patt71/ (accessed July 2020)

[35] Specialist Pharmacy Service. What is St Mark’s electrolyte mix (solution)? 2019. Available at: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/what-is-st-markos-electrolyte-mix-solution/ (accessed July 2020)

[36] Stomawise. Medications and your ostomy. 2013. Available at: http://www.stomawise.co.uk/types-of-stoma/medications-and-your-ostomy (accessed July 2020)

[37] NHS. Ileostomy — complications. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/ileostomy/risks/ (accessed July 2020)

[38] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Anaemia — B12 and folate deficiency. 2019. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/anaemia-b12-and-folate-deficiency#!diagnosissub:2 (accessed July 2020)