UrbanImages / Alamy Stock Photo

In ‘Polypharmacy: a framework for theory and practice’, a broad framework was suggested to be considered when undertaking polypharmacy reviews (see Box 1). This article will illustrate the application of these principles in a case study, which involved undertaking a comprehensive review. Tackling a smaller number of prioritised care issues in practice is equally valid.

The patient, Linda, consented to her case being used in this article.

Box 1: Framework to consider when undertaking polypharmacy reviews

- Aims — clarify what the patient is taking, whether they can manage their current medicines and any current support systems they have in place. Establish the patient’s wishes and priorities for their medicines, including others who are involved in their care, as appropriate.

- Need — review the need for each prescription by considering whether it is essential and has an ongoing valid indication.

- Effectiveness — ensure ongoing benefit of all agents in context of the patient’s frailty, life expectancy and wishes, the best available evidence and numbers needed to treat (NNTs). Consider quality (symptomatic treatment) versus quantity (preventative treatment) of life and outcomes important to the person.

- Safety — review current and future risks.

- Efficiency— consider whether medicine could be given in a cost-efficient, simpler manner.

- Acceptability — agree a plan for change with the patient and family/carers, as appropriate. Provide options, including maintaining status quo. Check the patient’s understanding.

- Document — ensure your plan is clearly documented and shared with others involved in the patient’s care.

- Monitor — follow-up with the patient and adjust as appropriate.

This framework should be viewed as a guide. Pharmacists may use existing national polypharmacy frameworks and resources to develop their own systematic approach to medication review.

Case study

A patient on multiple medicines who is struggling with symptoms and adherence

Linda is aged 64 years and has multiple health problems, struggling daily with mobility and pain. She lives at home with her husband, who assists her with daily tasks, and enjoys looking after her grandchildren.

Linda is attending the pharmacist-led polypharmacy clinic at her GP surgery in Fife for the first time and the systematic approach outlined in Box 1 is used during the consultation with her.

Presuming that she is taking her medicines as listed on the patient medical history should be avoided. In advance, ask her to bring her medicines to her appointment. Before the consultation, you could also post her a copy of the ‘Me and my Medicines’ charter — a way of encouraging conversation around medicines between the patient and healthcare professional — to support shared discussions[1]

.

Table 1 summarises the patient’s medical and drug history, and baseline laboratory values.

| Past medical history | Drug history | Baseline values |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Aims

First, ask Linda what matters to her in terms of her medicines; explore how she is currently using them and how they fit into her typical day. From the GP computer system, you know she is rarely collecting her co-codamol and fluticasone propionate nasal spray. You understand that adherence decreases as medicine burden rises and would like to explore this further in a non-judgemental way by asking Linda some questions[2]

.

Linda is not sure what all her medicines are for and is keen to take fewer, if it is safe. Specifically, she wants to know if her venlafaxine is still needed, because she has been taking this for some time.

She stopped taking her co-codamol and fluticasone proprionate nasal spray (Flixonase; GlaxoSmithKline UK) a while ago because she felt these were ineffective. However, she indicates she is still experiencing chronic pain and her priority is to improve control of this pain. She perceives nefopam as her “best” medicine and would “like to take more” if she could. Her tramadol intake is erratic and she reports taking them at 08:00, 16:00 and before bed. She says she is often busy during the day with her grandchildren and does not always have time to take all her analgesia.

Patient priorities

Linda wants to have better symptom control of her back and knee pain, and to take less medicine because she worries that “the tablets are taking over my life”.

Together, you agree that the aims of today’s appointment are to:

- Focus on improving her pain control;

- Identify opportunities to simplify her medication regimen and focus on venlafaxine at her request.

Need

Although Linda is prescribed a range of medicines, it is important to establish whether there is still an indication for these.

Consider original indications and treatment duration

By systematically matching Linda’s medicines to her coded patient medical history, you find no clear indication for:

- Aspirin — no personal history of vascular disease;

- Bumetanide — an unusual choice for hypertension, her only coded cardiovascular diagnosis;

- Fluticasone propionate nasal spray — a medicine she has stopped anyway.

Her medical history shows that aspirin was started during a hypertension review ten years ago and bumetanide was started for ankle oedema around three years ago. There are no cardiology letters on Linda’s file nor any references to heart failure, and an electrocardiogram during her most recent hypertension review showed normal sinus rhythm. Fluticasone propionate nasal spray was prescribed a few years ago during summer for allergic rhinitis.

Although Linda has a coded history of depression and acne rosacea, she has been taking venlafaxine and lymecycline continuously for eight and four years, respectively. This indicates the need to ask Linda about her mood and current rosacea symptom control.

Group by clinical indication

Grouping medicines together by indication is useful to identify tablet burden and potential therapeutic duplication. For Linda, this applies to her:

- Analgesia — co-codamol, tramadol and nefopam;

- Cardiovascular medicines — doxazosin, ramipril and bumetanide.

Consider the available evidence

Evidence suggests that aspirin should not be prescribed for patients such as Linda without overt cardiovascular disease, because certain risks (e.g. bleeding risk) outweigh benefits[3],[4]

. For patients aged over 55 years, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence hypertension guidelines favour a calcium-channel blocker as the antihypertensive of choice[5]

. In Linda’s case, as she has ongoing ankle oedema, it is reasonable not to favour this as a first-line agent.

In terms of venlafaxine, questioning its ongoing need is appropriate because Linda has been treated beyond standard treatment durations. According to national guidelines, patients should start treatment for six months initially, but anyone at risk of relapse should be treated for up to two years[6]

. This was Linda’s first course of antidepressants and they were started by her GP at the time of her daughter’s illness, which is now resolved. Linda reports her current mood as “good” and, following discussion with the initiating prescriber, gradual withdrawal seems appropriate.

Regarding Linda’s prescription for the antibiotic lymecycline, topical agents are recommended as first-line treatment[7]

. Both local and national guidelines advocate restricting oral antibiotic treatment to 12 weeks when they are deemed appropriate[7],[8]

. Thereafter, intermittent use, or periodic breaks in treatment — known as ‘drug holidays’ — should be considered. Linda describes her rosacea as “mild” and is willing to try a topical preparation to allow her to “cut out one more pill”.

Consider essential and non-essential items

Prior to any change to Linda’s bumetanide, the presence of heart failure (left ventricular systolic dysfunction) must be excluded through review of her records and enquiry around clinical symptoms. Case note review shows:

- Bumetanide was started for ankle oedema;

- There are no cardiology letters on file;

- There are no references to heart failure in records of Linda’s GP consultations;

- There is no echocardiogram on file;

- A recent electrocardiogram (ECG) showed normal sinus rhythm.

Linda is short of breath on mild exertion, but is notably obese. She is not short of breath at rest, nor does it wake her from sleep. National guidance is clear that diuretics are usually essential for symptom control in heart failure, but are not indicated for dependent ankle oedema (i.e. oedema which appears to be influenced by gravity)[9]

.

Effectiveness

Although Linda has a documented indication for several of her medicines, it is important to establish whether she is getting meaningful therapeutic benefit and to set realistic treatment goals for her.

Frailty

Though Linda is only aged 64 years, frailty is a stronger predictor of her vulnerability to medicine-related harm than age alone[10]

. She rises with effort from her chair in the waiting room and walks to the consulting room using a walking stick at a slow pace. When first asked about her general health, she describes day-to-day fatigue, limited physical activity and says she requires help from her husband for transportation, housework and in managing her medicines.

Using the Rockwood Clinical Frailty Scale (see ‘Polypharmacy: a framework for theory and practice’), you categorise Linda as ‘vulnerable’ or ‘mildly frail’[11]

.

Blood pressure

When agreeing realistic treatment goals for Linda’s blood pressure (BP) medicine, her comorbidities and frailty are relevant. Linda has no personal history of vascular disease, diabetes or other compelling indications for her cardiovascular medicine. It could therefore be argued that Linda’s BP control is tighter than required and could be relaxed, aiming for a target of <140/90mmHg.

Analgesics

Assessing benefit in relation to painkillers is important as they contribute significantly to Linda’s treatment burden. Multiple analgesics may be required to control Linda’s pain, but if she is taking them without benefit, she is at increased risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) without clear clinical gain.

Use of the SOCRATES mnemonic for pain assessment helps you establish relevant information about Linda’s pain:

- S ite — located primarily in her back and her knees;

- O nset — has been present for several years and is relatively stable;

- C haracter — presents as a dull ache;

- R adiate — does not radiate or travel to other parts of her body;

- A ssociation — is associated with constipation;

- T ime course — is worse in the middle of the day and when she is in bed;

- E xacerbating/Relieving factors — is exacerbated when she walks long distances and relieved by rest and heat;

- S everity — Linda reports remaining “very sore” despite her analgesics, rating her current pain as 7 out of 10 on a numerical rating scale (where 0 = no pain; and 10 = worst possible pain)[12]

.

Linda has been co-prescribed tramadol and co-codamol for several years, although has stopped co-codamol owing to lack of effectiveness. There is limited evidence to support long-term opioid use in chronic non-malignant pain and the co-prescribing of different strength opioids (e.g. tramadol and co-codamol) is not endorsed[13],[14],[15]

. In addition, opioids such as tramadol are best used in conjunction with non-opioid analgesic medicine (e.g. paracetamol), to minimise opioid dose and side effects[14]

. By discontinuing Linda’s co-codamol, Linda may not longer be benefiting from combining a step-1 analgesic (i.e paracetamol) with her other analgesics.

Although Linda believes nefopam to be her most effective painkiller, there is limited evidence of its effectiveness[16],[17]

. However, it is important to listen to Linda’s views. You may therefore choose not to prioritise changing nefopam at this point.

Linda’s obesity is relevant, but her pain currently limits her functional ability. Therefore, analgesia optimisation is required before Linda can be supported to increase her physical activity. Medicine administration timing is also important for effective analgesia with regular dosing preferred. This is relevant to Linda, whose current analgesia use involves large gaps between doses[16],[18],[19]

.

Overall, Linda agrees that her current painkiller regimen is cumbersome and not particularly effective, she is willing to consider different options for managing her pain.

Diuretics

In relation to Linda’s bumetanide, clinical examination reveals she is still troubled by swollen ankles and is unsure whether she has benefited from this ‘water pill’. Computer records show the dose was escalated six months ago from 1mg to 2mg daily, but nothing in the consultation indicates this resulted in increased clinical benefit. Linda confirms limited improvement in her fluid retention from the higher dose, but has “persevered”.

Aspirin

During the consultation, Linda confirms she has no personal history of stroke, coronary or peripheral vascular disease. To support an informed decision about stopping, you decide to use numbers needed to treat (NNT) data and published evidence[20]

.

When prescribed for primary prevention, NNT data show that aspirin has a very high annualised NNT (1,428) to prevent one serious vascular event. This, in combination with a discussion around recent evidence, shows that bleeding risk outweighs vascular benefits in patients without a personal history of vascular disease[3],[4]

. Following this, Linda is happy to stop her aspirin.

Safety

Potentially inappropriate prescriptions

Applying the ‘screening tool of older people’s potentially inappropriate prescriptions’ (STOPP) and Beers criteria tools to Linda’s medicines highlights the following:

- Loop diuretics are not indicated for dependent ankle oedema, nor first line for hypertension;

- Aspirin in patients with no history of coronary, cerebral or peripheral arterial events is not indicated;

- Alpha-blockers (e.g doxazosin) carry high risks of orthostatic hypotension, syncope and falls, and are not routinely recommended for hypertension[21],[22],[23]

:

Medstopper is an online deprescribing resource that references STOPP/START and STOPPFrail criteria, as well as Beers criteria, and assists risk prioritisation through assigning ‘medicine stopping priorities’[19],[20],[21]

. Medstopper ranks Linda’s aspirin and venlafaxine as the highest priority for stopping.

Risk of hospital admission

Linda takes five medicines that are considered high risk:

- Aspirin (antiplatelet medicine);

- Bumetanide (diuretic);

- Ramipril (an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor);

- Co-codamol and tramadol (opioid analgesic medicines);

- Venlafaxine (antidepressant medicine)[24],[25],[26]

.

Falls risk

Using the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale, Linda’s prescriptions for doxazosin, ramipril, codeine, tramadol and venlafaxine are all classed as high risk for falls, and bumetanide is classed as moderate risk for falls[27]

.

Cumulative toxicity

When considering drug–drug combinations and drug–disease interactions that increase Linda’s risk of ADRs, two medicines that increase risk of renal injury — ramipril and bumetanide — are noted. This is magnified by her pre-existing renal impairment. In the context of Linda’s most recent estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), the BNF indicates the current dose of ramipril may require reduction (maximum daily dose of 5mg if eGFR 30–60mL/min/1.73m2)[28]

.

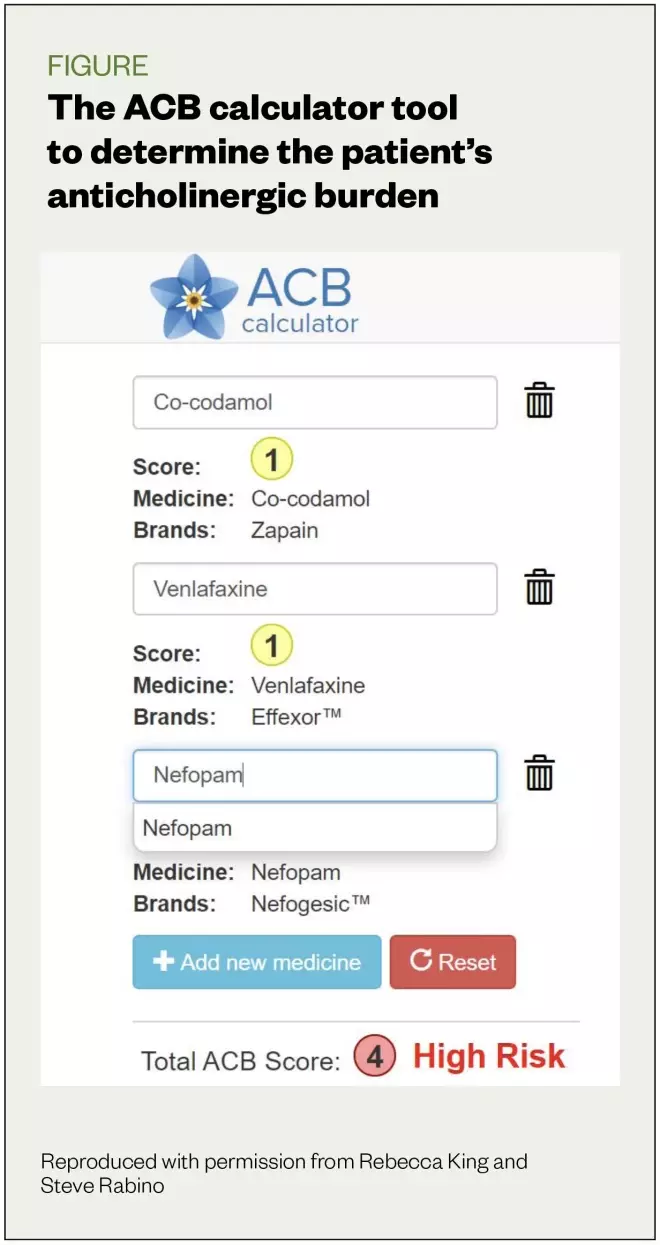

The concurrent prescription of tramadol and venlafaxine increases Linda’s risks of serotonin syndrome, and while she remains on both aspirin and venlafaxine, is at increased risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Linda’s anticholinergic cognitive burden (ACB) score reveals that Linda has a total ACB score of 4 (high risk), with nefopam having the highest individual drug score of 2 (see Figure).

Discrepancies between numerical ACB scores assigned to different medicines exist in the literature and among available scoring tools. Pharmacists should consider the pros and cons of available scoring systems and be able to justify their use of a certain system. For example, the ACB Calculator tool states that to avoid the under-estimation of risk, where discrepancies exist, they have chosen to use the highest available score for a medicine.

Figure: the ACB calculator tool

Source: Reproduced with permission from Rebecca King and Steve Rabino

Side effects

Linda does not immediately make the connection between any of her medicines and ADRs. However, specific questioning around anticholinergic side effects, such as dry mouth and falls, reveals that although Linda has not fallen recently, she does have a fear of falling. She describes her balance as “poor” and says she can be light-headed on rising. In addition, she feels sleepy and sluggish during the day and says she often has a dry mouth and always feels thirsty. Urinary symptoms resulting from the larger dose of her diuretic trouble her, as she stated “I always need to know where the next toilet is”.

You decide to proactively check lying and standing BP based on:

- Linda’s self-reported dizziness on rising;

- Knowledge that one in five older adults living at home experience postural hypotension[29]

; - Linda’s multiple anti-hypertensive medicines;

- The link between doxazosin and postural hypotension highlighted in Beers and STOPP/START and STOPPFrail criteria[19],[20],[21]

.

Postural hypotension is defined as systolic drop of greater than 20mmHg and diastolic drop of greater than 10mmHg within three minutes of standing compared with sitting or supine position[30],[31]

. Linda’s BP of 116/76mmHg (lying) and 120/74mmHg (standing) do not meet the criteria for postural hypotension. However, both readings are low in the context of her frailty and lack of vascular history.

The potential impact of venlafaxine on Linda’s BP control is worth considering, as this serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor is not recommended in patients with uncontrolled hypertension[32]

. However, Linda currently has low BP (venlafaxine is more commonly associated with hypertension) and the core issue for her is the review and de-escalation of her anti-hypertensive medicine.

Efficiency

Cost-effectiveness

Linda already takes the most cost-effective formulations of many of her medicines, for example: ramipril (capsules as opposed to tablets); co-codamol (tablets as opposed to capsules or effervescent formulations); and doxazosin (standard as opposed to modified release [MR] tablets). However, the following points need to be considered:

- Venlafaxine has a higher acquisition cost than other recommended first-line antidepressant drugs, such as fluoxetine;

- Fluticasone proprionate nasal spray is more expensive than other first-line generic agents e.g. beclomethasone nasal spray;

- Lymecycline costs more than oral oxytetracycline or topical metronidazole, which are recommended first-line treatments for acne rosacea;

- Nefopam is a non-formulary analgesic in NHS Fife and has been identified as not cost effective by the PrescQIPP bulletin[16]

.

Importantly, medicines are only cost effective if:

- They have clear ongoing indications;

- Patients are willing and able to take them as prescribed;

- They provide clinical benefit.

For venlafaxine and aspirin, evidence of ongoing need is lacking, and savings can be achieved by reducing or stopping these high-risk drugs. Linda already admits non-adherence with fluticasone propionate and co-codamol and therefore, both can be removed from her repeat list to avoid accidental re-ordering.

Simplicity

Linda is on an unusual dose of doxazosin, requiring her to take two different strengths (4mg and 2mg). You aim to tackle this as part of your plan to pull back on Linda’s antihypertensive medicine intake.

If venlafaxine was still required, a once-daily MR formulation may have reduced the complexity of Linda’s regimen, albeit at a higher cost.

Tramadol (as standard capsules) is the most cost-effective formulation, but may not offer value for money as Linda struggles to fit four-to-six hourly dosing into her day and, therefore, benefit may be limited. If MR formulations of tramadol were selected, then PrescQIPP recommends generic MR capsules, as tablets are not currently listed in part VII of the Drug Tariff[16]

. If this is locally endorsed as a cost-saving approach, there is an option to prescribe branded generics[16]

.

Moving from an oral to a topical antibiotic for Linda’s rosacea offers another chance to reduce her tablet burden.

Acceptability

Agree a plan for change

Reviewing the information gathered from the previous sections, you are clear that Linda is:

- Taking several high-risk medicines;

- Potentially lacking a valid ongoing clinical indication for aspirin, lymecycline, venlafaxine and bumetanide;

- Is experiencing medicine-related side effects (e.g. urinary frequency, daytime fatigue and poor balance).

There are many opportunities for change, but it remains crucial to discuss and agree a prioritised plan for change that is acceptable to Linda. It is important to discuss benefits and risks of each of Linda’s medicines in a way she understands, and to decide jointly on either to continue the current regimen or to make changes and how this will be managed.

The Tasmanian Primary Health Network provides online guidance on the appropriateness of abrupt and tailored stops for individual medicines[33]

. For example, an immediate stop of aspirin and lymecycline is appropriate, whereas venlafaxine and bumetanide require more gradual reductions. There are also several helpful websites supporting shared decision making with patients (see Useful resources).

Venlafaxine

Linda says she is particularly keen to review her ongoing need for an antidepressant. Targeting venlafaxine for change is reasonable because you have previously identified it as a high-risk falls medicine (ACB score of 1). It also increases GI risk in combination with aspirin. Dizziness and sedation are common side effects, both of which Linda has been experiencing and would be keen to reduce.

Antidepressants are a class of specialist drugs where discussion with the original prescriber is advised to plan whether and how to discontinue[8]

. In Linda’s case, her venlafaxine was initiated by her regular GP, who agrees to a planned withdrawal when you approach them for advice.

Following tapering advice from Medstopper, you agree to reduce venlafaxine slowly from 37.5mg twice daily to 37.5mg once at night, dropping the morning dose in view of Linda’s daytime fatigue[34]

.

Pain medicines

For Linda’s analgesia, you agree to remove co-codamol from her repeat list because she has not been taking it, nor is it recommended in combination with her tramadol. You both agree to focus on the regularity of Linda’s other analgesics by suggesting to change her tramadol from two 50mg capsules three times per day (at 08:00, 16:00 and before bed), to a slightly lower overall daily dose of one 50mg capsule four times per day. Although this requires Linda to take her tramadol more frequently, it reduces the overall number of capsules from six to four daily, and may improve the fatigue and dizziness that she has been experiencing.

You discuss the possibility of MR tramadol if Linda struggles with four times per day dosing, but currently, Linda is happy to try the short-acting formulation and to link her dosage to breakfast, lunch, dinner and bedtime to support regular dosing.

You would like to discuss her nefopam further, because it is a high-risk drug, but owing to Linda’s perceived views that this is her most effective painkiller, you agree not to change this now. It is something to be reviewed in the future.

Although Linda wishes to reduce the number of tablets, you explain you would like to try reintroducing regular paracetamol because this may allow further future reductions in her stronger painkillers, tramadol and nefopam. As a result, it will reduce her risk of falls, sedation and dizziness. You ask Linda to report any benefits to her pain, day-to-day function or if she experiences better quality sleep following a four-week trial of paracetamol, using your baseline numerical pain score of 7 out of 10. You agree to stop this if there is no obvious benefit.

It is important also to discuss with Linda that medicine is only part of the available treatment for her pain and to encourage her to consider additional non-pharmacological approaches, such as exercise, pacing (process of balancing activities and rest) and the application of heat.

Cumulative risk

You agree to stop Linda’s aspirin explaining this also avoids the need for an extra pill for gastro-protective effects had she continued in combination with venlafaxine.

Blood pressure

Linda’s BP and the use of three antihypertensives, ramipril, bumetanide and doxazosin, is another clinical priority. However, there has been a sufficient amount of clinical changes in this consultation.

You spend some time discussing the Scottish patient safety programme ‘sick day rules’ advice , which applies to Linda’s ramipril and bumetanide[35]

. Both of these medicines increase the risk of acute kidney injury if they are continued during an episode of acute dehydrating illness, for example, diarrhoea, vomiting or fever. You also arrange a phlebotomist appointment to recheck Linda’s renal function, which was most recently checked nine months ago.

You mention that you would like to tackle doxazosin first because its dosing is cumbersome (two different tablet strengths) and it is strongly associated with falls and dizziness. The review of Linda’s antihypertensives is an example of clinical decision making where there is more than one option. It would be equally reasonable to argue for an initial trial reduction in bumetanide, another potentially high-risk agent that is causing side effects (e.g. urinary frequency), which reduce Linda’s quality of life, or a reduction in ramipril in line with Linda’s current renal function.

Acne rosacea

You agree not to change Linda’s acne treatment today, but document in the future that Linda is keen to move from tablets to a topical preparation to reduce her tablet burden further.

Summary

The following changes to Linda’s prescriptions have been made:

- Reduction in venlafaxine to 37.5mg once daily at night;

- Removal of co-codamol and fluticasone propionate from her repeat list as she is no longer taking them;

- Stop aspirin 75mg once daily;

- Change in tramadol dosing from 100mg three times daily to 50mg four times daily;

- Addition of regular paracetamol.

It is important to check that Linda has understood this plan. ‘Teach-back’ is a useful tool for this — ask her to explain her understanding of what has been agreed and what will happen next[36]

.

Document

Consider providing Linda with a written summary of the agreed changes to take away and, with her permission, share with her husband who provides support in relation to managing her medicines.

After the consultation, using your notes, you document your agreed changes, rationale, how you will monitor these and your plan for follow-up. Table 2 shows how Linda’s initial pharmaceutical care plan was documented within the GP system.

| Comment | Polypharmacy medication review Medication review done by pharmacist Seen in GP’s surgery |

| Additional | Medicine discontinued: aspirin 75mg, once daily Medicine decreased: tramadol 50mg, two three times per day to one 50mg four times per day; venlafaxine 37.5mg, twice daily to one at night Medicine started: paracetamol two 500mg tablets, four times per day Medication counselling: sick day rules card issued Previous treatment: continue unchanged, patient declines change to nefopam at present |

| Problem | Unclear indication for aspirin |

| Comment | Started for primary prevention in the context of hypertension. No personal history of stroke or myocardial infarction. Also on serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor in the form of venlafaxine so increased gastrointestinal risk from the combination of drugs Plan: Stop aspirin, patient happy with decision |

| (Review) Problem | Depressive disorder |

| Comment | Been on venlafaxine 37.5mg twice daily for eight years. Initially discussed the possibility of switching to 75mg modified release once daily for simplicity, but patient feels her mood and anxiety have been good for past three years and she is unsure if she still needs this prescribed. Would be keen to try a reduction in dose. This may also be beneficial in the context of her hypertension and ankle oedema for which venlafaxine is a risk factor Plan: Trial reduction in dose to 37.5mg at night with follow up in two weeks. Signposted to return to original dose if symptoms recur following reduction |

| Problem | Pain control |

| Comment | Takes two tramadol three times per day and nefopam 30mg, three times per day (patient indicates she would like to take more of these). Co-codamol is on her repeat, but she does not use these. There are huge gaps between her painkillers, which she takes at 08:00, 16:00 and before bed Plan: Delete co-codamol from repeat (as not using). Add in paracetamol two four times per day and suggest a reduction in tramadol from two tablets three times per day, to one tablet four times per day. Review in two weeks. Aim for reduction in nefopam if this is successful |

| Problem | Rosacea |

| Comment | Has been taking lymecycline for several years. Not sure if they are helping. Discussed rosacea guideline, which advocates oral antibiotics for 12 weeks and repeated intermittently if need be. Also discussed topical versus oral antibiotics and she remembers trying and liking metronidazole gel in the past Plan: Do not want to change too much at once. At follow up, consider stopping lymecycline and trial metronidazole 0.75% gel |

| Problem | Hypertensive disease |

| Comment | On ramipril 10mg, doxazosin 6mg (two doses of 4mg and 2mg) and bumetanide 2mg. Patient’s estimate glomerular filtration rate is reduced at 47 (creatinine clearance: 38mL/min). Blood pressure when most recently checked seems good at 115/84mmHg. Sick day rules card issued. Could doxazosin (and venlafaxine) be driving some of the oedema? Plan: At next appointment, check sitting and standing blood pressure and, if well controlled (or postural drop), consider reduction in doxazosin to 4mg, once daily |

Patient clinical record and care plan reproduced with permission of the patient and Fiona Allan | |

To improve joined-up care and allow broader support for Linda in managing these changes, seek Linda’s permission to share your plan with the local community pharmacy. Linda does not regularly see any hospital consultants or practitioners outside of your practice team. However, if she did, it might have been useful to share a summary of the plan with them. ‘My medication passport’ is one method of supporting transfer of medicine-related information across the interface[37]

.

Monitor

To ensure your plan is both safe and effective, ongoing monitoring of Linda’s pain, mood and anxiety is required. See ‘Polypharmacy: a framework for theory and practice’ for suggested validated tools to assist in objectively monitoring change, such as visual analogue pain scores, anxiety and depression scoring tools. If Linda’s doxazosin and bumetanide are subsequently reviewed, then changes to clinical symptoms, such as shortness of breath and leg oedema, should be assessed. Clinical parameters, such as BP and renal function, must also be monitored.

In relation to her immediate changes, agree to contact Linda by phone in two weeks to see how she is managing. Make a follow-up, face-to-face appointment for four weeks time and emphasise her husband would be very welcome to attend this. For safety purposes, advise that she contacts you, the practice team or her community pharmacist if she encounters problems between now and when you next speak, specifically around any worsening of her pain, mood or anxiety.

Over the next few months, you and Linda meet a further three times and, eventually, Linda’s medicines reach stability (see Table 3).

| Pre-review | Post-review | Change |

|---|---|---|

| Aspirin 75mg, once daily | — | Stopped |

| Nefopam 30mg, twice daily | — | Stopped |

| Venlafaxine 37.5mg, twice daily | — | Stopped |

| Fluticasone propionate nasal spray, two sprays, as required | — | Stopped |

| Doxazosin 6mg (2mg and 4mg), once per day | Doxazosin 4mg, once daily | Dose reduced |

| Bumetanide 1mg, twice daily | Bumetanide 1mg, daily | Dose reduced |

| Tramadol 50mg, two twice daily | Tramadol 50mg, four times per day | Dose reduced |

| Co-codamol 30/500, two tablets as required | Paracetamol 1g, four times per day | Replaced |

| Lymecycline 408mg, once daily | Topical metronidazole gel | Replaced |

| Ramipril 10mg, once daily | Ramipril 10mg, once daily | Unchanged |

Venlafaxine has now been stopped completely and Linda’s mood remains good. Linda was also able to fully discontinue her nefopam, initially moving to ‘as required’ use in combination with regular tramadol and paracetamol, which had greatly improved her pain. Linda’s BP control allowed her to reduce her doxazosin from 6mg to 4mg once daily. This was followed by a reduction in her diuretic dose from bumetanide 2mg to 1mg daily and an improvement in Linda’s dry mouth and urinary symptoms. Overall, Linda felt less sleepy and dizzy, and her mobility improved.

It is important when reviewing patients to know when further deprescribing is inappropriate. For Linda, complete discontinuation of her bumetanide was not an option she wished to consider, but she is aware she could revisit the issue in the future if improvements in mobility and weight loss reduce her oedema further.

Outcomes

Polypharmacy reviews should not be one-off interactions and pharmacists must be mindful that best outcomes are achieved through careful follow-up and by adopting a partnership approach with patients and other professionals involved in their care.

Main outcomes at patient level

Linda’s overall number of medicines reduced from ten to six in line with her desire to reduce medicines complexity. More importantly, Linda’s pain has improved, she feels better (less drowsy and constipated) and is managing her medicines well. Linda’s falls risk is reduced (ACB score reduced from 4 to 0 through discontinuing venlafaxine, co-codamol and nefopam), her GI risk is lowered by discontinuing her aspirin and venlafaxine, and her risk of renal injury is lowered by reducing her diuretic.

The direct cost savings associated with Linda’s drug changes were calculated as approximately £400/annum.

Main outcomes at health board level

On a wider scale, an evaluation of face-to-face polypharmacy reviews undertaken in a larger cohort of 180 patients within NHS Fife show that:

- Medicine change, particularly around high-risk medicines, can be achieved, with 55% of interventions related to medicine reductions/discontinuations; and 60% of reduced and 49% of stopped medicines were ‘high risk’;

- Changes showed high levels of sustainability, with 86% maintenance at six months follow up;

- Reviews were well received by patients, with 88% of patients willing to attend a pharmacist-led clinic again; and 88% happy with appointment outcomes;

- Annualised drug savings of approximately £200/patient were achieved[38]

.

Useful resources

Deprescribing guides

- Primary Health Network Tasmania. Deprescribing resources. 2019. Available at: https://www.primaryhealthtas.com.au/resources/deprescribing-resources

- Deprescribing.org. Deprescribing information pamphlets. 2019. Available at: https://deprescribing.org/resources/deprescribing-information-pamphlets

Shared decision making

- NHS Scotland. Polypharmacy Guidance. Shared decision making. Available at: http://www.polypharmacy.scot.nhs.uk/polypharmacy-guidance-medicines-review/shared-decision-making

- University of Ottawa. Patient decision aids. 2019. Available at: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/index.html

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Search results for ’patient decision aids’. Available at: https://www.evidence.nhs.uk/search?q=patient+decision+aids

References

[1] All Wales Medicines Strategy Group. Polypharmacy: Guidance for Prescribing. 2014. Available at: http://awmsg.org/docs/awmsg/medman/Polypharmacy%20-%20Guidance%20for%20Prescribing.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[2] Capodanno D & Angiolillo DJ. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Lancet 2018;392(10152):988–990. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31990-1

[3] McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL et al. Effect of Aspirin on All-Cause Mortality in the Healthy Elderly. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1519–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803955

[4] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in adults. Quality standard [QS28]. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs28 (accessed December 2019)

[5] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults. Quality standard [QS8]. 2011. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/QS8 (accessed December 2019)

[6] NHS Fife Area Drugs and Therapeutics Committee. NHS Fife Formulary — Chapter 13: Skin. 2019. Available at: https://www.fifeadtc.scot.nhs.uk/media/2357/chapter13-final-july-2017-amended-sept-19.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[7] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Rosacea — acne. Clinical knowledge summary. 2018. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/rosacea-acne#!scenario (accessed December 2019)

[8] Scottish Government Polypharmacy Model of Care Group. Polypharmacy Guidance Realistic Prescribing. 2018. Available at: https://www.therapeutics.scot.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Polypharmacy-Guidance-2018.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[9] Rajkumar C, Ali K & Parekh N. Frailty predicts medication-related harm requiring healthcare: a UK multicentre prospective cohort study. 2018. Available at: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/77388 (accessed December 2019)

[10] Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381(9868):752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9

[11] Schofield M, Shetty A, Spencer M & Munglani R. Pain Managment: Part 1. Br J Fam Med 2014;2(3)

[12] British Medical Association. Chronic pain: supporting safer prescribing of analgesics. 2017. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/-/media/files/pdfs/collective%20voice/policy%20research/public%20and%20population%20health/analgesics-chronic-pain.pdf?la=en (accessed December 2019)

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Medicines optimisation in chronic pain. Key therapeutic topic [KTT21]. 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/KTT21 (accessed December 2019)

[14] Abdulla A, Adamas N, Bone M et al. Guidance on the management of pain in older people. Age Ageing 2013;42:(Suppl 1);i1–i57. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs200

[15] PrescQIPP. Management of non-neuropathic pain. 2017. Available at: https://www.prescqipp.info/media/1483/149-non-neuropathic-pain-23.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[16] NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service and UK Medicines Information. What is the evidence to support the use of nefopam for the treatment of persistent/chronic pain? 2017. Available at: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/UKMi_QA_nefopam_Jul_2017_final.docx (accessed December 2019)

[17] NHS Fife. Fife Integrated Pain Management Service. Appendix 4C: Guidance on the Management of Chronic Non-Malignant Pain. 2017. Available at: https://www.fifeadtc.scot.nhs.uk/media/2183/appendix-4c-guidance-on-management-of-chronic-non-malignant-pain-feb-17-including-buprenorphine-statement.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[18] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Analgesia — mild-to-moderate pain. Clinical knowledge summary. 2015. Available at https://cks.nice.org.uk/analgesia-mild-to-moderate-pain (accessed December 2019)

[19] O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne Set al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 2015;44(2):213–218. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145

[20] Lavan AH, Gallagher P, Parsons C & O’Mahony D. STOPPFrail (screening tool of older persons prescriptions in frail adults with limited life expectancy): consensus validation. Age Ageing 2017;46(4):600–607. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx005

[21] American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria update expert panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(4):674–694. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767

[22] Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18,820 patients. BMJ 2004;329:15–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15

[23] Howard RL, Avery AJ, Slavenburg Set al. Which drugs cause preventable admissions to hospital? A systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63(2):136–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02698.x

[24] Dreischulte T & Guthrie B. High-risk prescribing and monitoring in primary care: how common is it, and how can it be improved? Ther Adv Drug Saf 2012;3(4):175–184. doi: 10.1177/2042098612444867

[25] Darowski A, Dwight J & Reynolds J. Medicine and Falls in Hospitals guidance sheet. 2011. Available at: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/file/933 (accessed December 2019)

[26] BNF. 2017. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk (accessed December 2019)

[27] Aging Brain Program of the Indiana University Center for Aging Research. Anticholinergic cognitive burden scale. 2012. Available at: http://www.miltonkeynesccg.nhs.uk/resources/uploads/ACB_scale_-_legal_size.pdf (accessed December 2019)

[28] Lanier JB, Mote MB & Clay E. Evaluation and management of orthostatic hypotension. Am Fam Physician 2011;84(5):527–536. PMID: 21888303

[29] Gupta V & Lipsitz LA. Orthostatic hypotension in the elderly: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Med 2007;120(10):841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.02.023

[30] eMC. Summary of product characteristics. Venlafaxine. 2015. Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/24329# (accessed December 2019)

[31] Healthcare Improvement Scotland. Scottish patient safety programme — primary care. Medicines sick day rules card. 2018. Available at: https://ihub.scot/improvement-programmes/scottish-patient-safety-programme-spsp/spsp-primary-care/medicines-sick-day-rules-card (accessed December 2019)

[32] McDonagh ST, Mejzner N & Clark CE. Prevalence of postural hypotension in primary care, community and institutional care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Society for Academic Primary Care. 2018. Available at: https://sapc.ac.uk/conference/2018/abstract/prevalence-of-postural-hypotension-primary-care-community-and-institutional (accessed December 2019)

[33] Primary Health Network Tasmania. Deprescribing resources. 2019. Available at: https://www.primaryhealthtas.com.au/resources/deprescribing-resources (accessed December 2019)

[34] Me and My Medicines. The medicines communication charter. 2018. Available at: https://meandmymedicines.org.uk/the-charter (accessed December 2019)

[35] The NNT. Quick summaries of evidence-based medicine. 2010. Available at: http://www.thennt.com (accessed December 2019)

[36] Scottish Health Council. Teach-back. 2014. Available at: http://scottishhealthcouncil.org/patient__public_participation/participation_toolkit/teach-back.aspx#.XDIbWvZ2vIU (accessed December 2019)

[37] Medstopper. 2015. Available at: http://medstopper.com (accessed December 2019)

[38] National Institute for Health Research. My medication passport. 2018. Available at: http://clahrc-northwestlondon.nihr.ac.uk/resources/mmp (accessed December 2019)