Steve Gschmeissner / Science Photo Library

Summary

The risk of developing prostate cancer increases with age after 50 years, although risk increases after the age of 40 years in patients who have a first-degree relative with a history of prostate cancer. This approximately doubles the lifetime risk of developing prostate cancer; this risk is higher for men who have a brother with a history of prostate cancer than for those who have an affected father. Early stage prostate cancer is generally asymptomatic, as many prostate cancers start in the posterior peripheral zone (the outer part of the prostate away from the urethra). It is not until the tumour has grown large enough to put pressure on the urethra that symptoms are noticeable. Locally advanced prostate cancer will most commonly cause bladder outlet obstruction, with a small proportion of patients experiencing haematuria, urinary tract infections, irritation on passing urine or erectile dysfunction. Many of the symptoms of prostate cancer are also present in benign prostatic hyperplasia. In the UK, patients presenting to their GP with symptoms that suggest prostate cancer (e.g. lower urinary tract symptoms, such as nocturia, urinary frequency, hesitancy, urgency or retention or erectile dysfunction or visible haematuria) are given a digital rectal examination and prostate specific antigen blood test.

Cancer learning ‘hub’

Pharmacists are playing an increasingly important role in supporting patients with cancer, working within multidisciplinary teams and improving outcomes. However, in a rapidly evolving field with numbers of new cancer medicines is increasing and the potential for adverse effects, it is now more important than ever for pharmacists to have a solid understanding of the principles of cancer biology, its diagnosis and approaches to treatment and prevention. This new collection of cancer content, brought to you in partnership with BeOne Medicines, provides access to educational resources that support professional development for improved patientRisk factors

Age is the most important risk factor for developing prostate cancer, with the risk generally increasing with age after 50 years, although the risk increases after the age of 40 years in patients with a first-degree relative with a history of prostate cancer[3] . This approximately doubles the lifetime risk of developing prostate cancer; this risk is higher for men who have a brother with a history of prostate cancer than for those who have an affected father. Unlike other cancers, where increased understanding of the molecular biology of the disease at a cellular level has led to identification of risk factors, there are currently no common specific gene mutations that are associated with prostate cancer risk as the full range of prostate cancer genomic alterations are incompletely characterised[4] . Ethnicity is a significant risk factor in prostate cancer, although the reason for racial variability is currently unknown. The highest incidence of prostate cancer worldwide is found in American black men, who have around a 9.8% lifetime risk of developing prostate cancer; 1.6 times that of white men[3] . In the UK, black men also have a substantially greater risk of developing prostate cancer compared with white men. although this risk is lower than that of American black men[5] . Japanese and Chinese men have the lowest rates of prostate cancer[3] . Socioeconomic status appears to be unrelated to the risk of prostate cancer[3] . Dietary factors were thought to play a part in prostate cancer risk, with high levels of dietary fat associated with an increased risk and cruciferous vegetables (e.g. broccoli) associated with a reduced risk. However, no study to date has proven that diet and nutrition are either causative or preventative factors for the development of prostate cancer. Vasectomy may increase the relative risk of prostate cancer, according to data from several large epidemiologic studies; however, these studies did not report an increased risk of dying from prostate cancer associated with vasectomy, so any link remains unproven[3] . Regular ejaculation may reduce prostate cancer risk. A large prospective study of more than 29,000 men demonstrated an association between high ejaculatory frequency (more than 21 ejaculations/month) and a decreased risk of prostate cancer, with a lifetime relative risk of 0.67, compared with men who reported a lower ejaculatory frequency[6] . The reliability of this study had previously been questioned because of its short follow-up, however, more recent follow-up data confirm the original findings and have provided the firmest evidence to date that men can decrease their risk of prostate cancer by ejaculating frequently[7] . The Health Professionals Follow-up Study followed nearly 32,000 healthy men for 18 years, 3,839 of whom were later diagnosed with prostate cancer. All participating men were asked to report their average monthly frequency of ejaculation from the ages of 20–29 years, 40–49 years and for the previous year, which allowed calculation of a lifetime average. After potential confounders were controlled for, the risk of prostate cancer was 20% lower in men who ejaculated at least 21 times a month than in men who ejaculated between four and seven times a month (P<0.0001)[7] .Symptoms of prostate cancer

As men age, their prostate gland often enlarges, most commonly caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). The exact cause of BPH is unknown, but it is likely to be a normal part of the ageing process in men, caused by changes in hormone balance and cell growth. There is no definite link between BPH and prostate cancer, as BPH does not usually develop into cancer and men can develop prostate cancer without having first experienced BPH. However, an enlarged prostate may sometimes contain areas of cancer cells, and men with BPH can develop prostate cancer. BPH commonly manifests as problems passing urine (more frequently, difficulty in passing and passing at night). Early stage prostate cancer is generally asymptomatic, as many prostate cancers start in the posterior peripheral zone (the outer part of the prostate away from the urethra). It is not until the tumour has grown large enough to put pressure on the urethra that symptoms are noticeable. Locally advanced prostate cancer will most commonly cause bladder outlet obstruction, with a small proportion of patients experiencing haematuria, urinary tract infections, irritation on passing urine or erectile dysfunction. Many of the symptoms of prostate cancer are also present in BPH, and there is a lack of symptoms to aid early detection and diagnosis. Prostate cancer is usually slow growing and can be present for a number of years before it is detected. Men with advanced disease can present with bone pain from bony metastases and occasionally bilateral lower leg oedema from bulky lymph node metastases.Diagnosis

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has issued guidance on diagnosis of prostate cancer[8] . Patients presenting to their GP with symptoms that suggest prostate cancer (e.g. nocturia, urinary frequency, hesitancy, urgency, retention, erectile dysfunction or visible haematuria) are given a digital rectal examination (DRE) and prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test[9] . Urinary tract infections should be ruled out prior to performing a PSA test. Patients who have had a urine infection should not undergo a PSA test for at least a month after treatment finishes[10] . There is no single PSA level that is considered ‘normal’ as it varies from man to man and the normal level increases with age. As a guide:- 3ng/mL or less is normal for a man aged under 60 years;

- 4ng/mL or less is normal for a man aged 60–69 years;

- 5ng/mL or less is normal for a man aged over 70 years.

- Men who choose to be tested who have a PSA of less than 2.5ng/mL may only need to be retested every two years;

- Screening should be conducted yearly for men whose PSA level is 2.5ng/mL or higher.

Staging

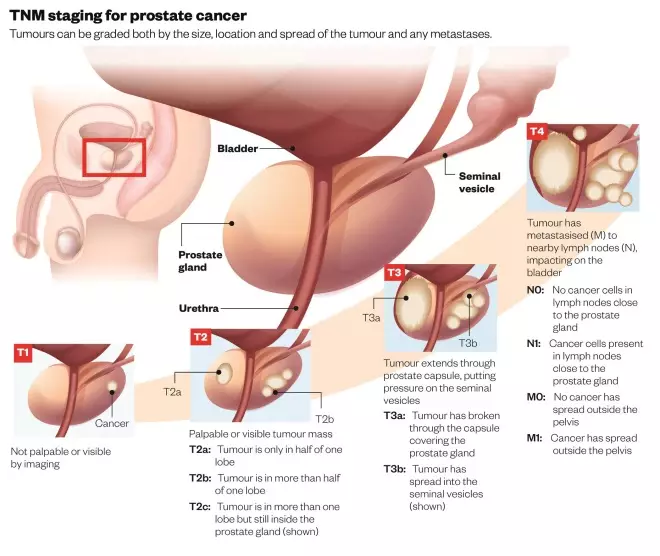

Prostate cancer staging can be complex because various staging, grading and classification systems are used either alone or in combination. It is most usefully described as one of three stages:- localised

- locally advanced

- metastatic

TNM staging for prostate cancer

Tumours can be graded both by the size, location and spread of the tumour and any metastases.

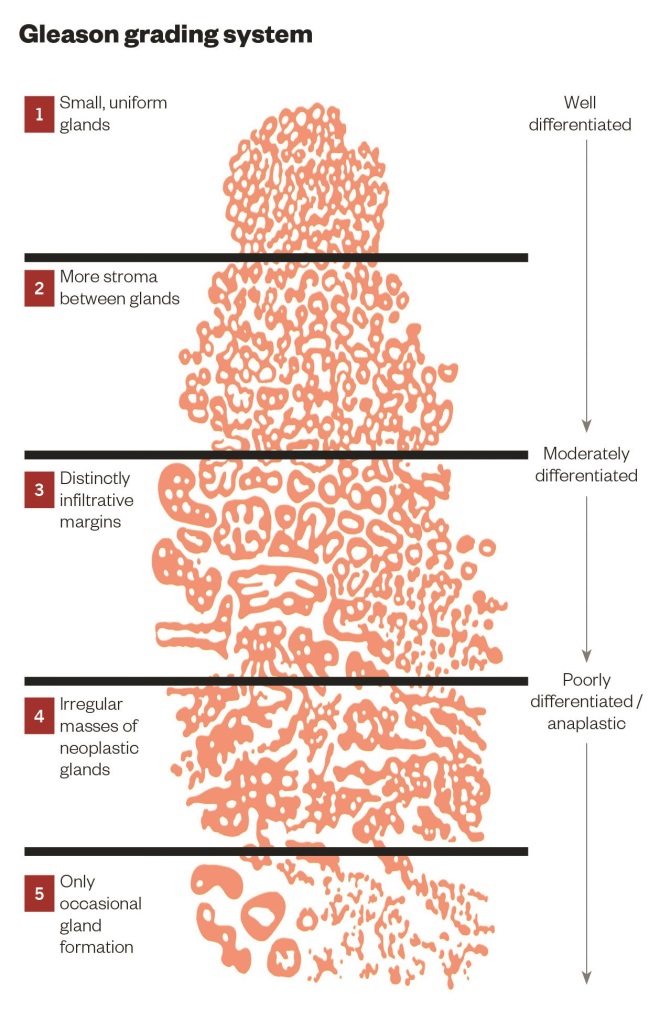

Gleason grading system

- Low-risk: PSA of less than or equal to 10ng/mL, Gleason score of less than or equal to 6, and clinical stage T1-2a

;

- Intermediate risk: PSA of between 10ng/mL and 20ng/mL, Gleason score of 7, or clinical stage T2b

;

- High-risk: PSA of more than 20ng/mL, Gleason score of equal to or larger than 8, or clinical stage T2c-3a;

References

[1] Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1374–1403.

[2] Cancer research UK. Prostate cancer statistics. Available at: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/prostate-cancer#heading-One (accessed June 2015).

[3] Moul JW, Armstrong A & Lattanzi J. Prostate Cancer. In: Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach Medical, Surgical, & Radiation Oncology. Available at: http://www.cancernetwork.com/cancer-management (accessed 2015).

[4] Berger MF, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F et al. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature 2011;470:214–220.

[5] Ben-Shlomo Y, Evans S, Ibrahim F et al. The risk of prostate cancer amongst black men in the United Kingdom: the PROCESS cohort study. Eur Urol. 2008;53(1):99–105.

[6] Leitzmann MF, Platz EA, Stampfer MJ et al. Ejaculation Frequency and Subsequent Risk of Prostate Cancer. JAMA 2004;291:1578–1586.

[7] American Urological Association (AUA) 2015 Annual Meeting: Abstract PD6-07. Presented 15 May 2015.

[8] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidelines. Prostate cancer: diagnosis and treatment [CG175] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg175/resources/guidance-prostate-cancer-diagnosis-and-treatment-pdf (accessed June 2015).

[9] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidelines. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral [NG12]. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12 (accessed June 2015).

[10] Cancer Research UK. Prostate cancer tests. Available at: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/type/prostate-cancer/diagnosis/prostate-cancer-tests (accessed June 2015).

[11] Hugosson J, Carlsson S, Aus G et al. Mortality results from the Goteborg randomised population-based prostate-cancer screening trial. Lancet Oncology 2010;11:725.

[12] Ilic D, O’Connor D, Green S et al. Screening for prostate cancer: an updated Cochrane systematic review. BJU Int 2011;107:882.

[13] Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ et al; ERSPC Investigators. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med 2009;360(13):1320–1328.

[14] The UK NSC recommendation on Prostate cancer screening/PSA testing in men over the age of 50. Available at: http://www.screening.nhs.uk/prostatecancer (accessed 2015).

[15] American Urological Association (AUA) Guideline — Early Detection Of Prostate Cancer: April 2013. Available at: https://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Prostate-Cancer-Detection.pdf (accessed June 2015).

[16] Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer, 2010.

[17] Gleason DF. Classification of prostatic carcinomas. Cancer Chemother Rep 1966;50:125–128.

[18] D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB et al. Pretreatment nomogram for prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy or external-beam radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17(1):168–172.

[19] Crawford ED, Ventii K & Shore ND. New biomarkers in prostate cancer. Oncology 2014;28(2):135–142.