Paula Solloway / Alamy Stock Photo

Following the concerns raised at Winterbourne View Hospital in Gloucestershire, the UK’s Department of Health (DH), a ministerial department responsible for government policy on health and social care, issued a report in 2012 that identified the overuse of antipsychotic and antiÂdepressant medicines in people with learning disabilities (PwLD)

[1]. Recommendations within this report suggested that medication reviews are conducted in a timely manner and involve pharmacists, doctors and nurses.

The DH describes “learning disability” as a “significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information, to learn new tasks and a reduced ability to cope independently, which begins before adulthood”[2]

. The term is often used interchangeably with the internationally agreed term “intellectual disability”[2]

.

The purpose of this article is to examine ways in which pharmacists can engage and be part of a strategy to review and reduce inappropriate prescribing of psychotropic medicines in PwLD safely and effectively. This article will focus primarily on the use of antipsychotics in PwLD.

Current antipsychotic prescribing in PwLD

Recent reports commissioned by NHS England have highlighted that there is a significantly higher rate of prescribing of medicines associated with mental illness among PwLD than in the general population; often more than one medicine in the same class is prescribed and, in the majority of cases, with no clear clinical justification[3],[4],[5]

. Although it is documented that PwLD have higher rates of mental health comorbidities[6],[7],[8]

, there is evidence to suggest that the medications are being prescribed on a long-term basis in the absence of documented mental health diagnoses[3],[4],

[5]

.

A report by Public Health England, an executive agency of the DH in the UK, into the prescribing of psychotropic drugs to PwLD and/or autism by GPs in England found that 58% of adults receiving antipsychotics and 32% of those receiving antidepressants had no recorded relevant diagnosis of a mental health condition[3]

. In addition, 22.5% of prescriptions for antipsychotics included more than one medicine in this class and 5.5% were for doses exceeding the recommended maximum[3]

.

Similarly, a UK cohort study conducted by Sheehan et al. found that of the 33,016 PwLD reviewed, only 21% of the cohort had a record of mental illness and 25% had a record of challenging behaviour, however, 49% were prescribed psychotropic medicines[9]

.

Behaviour that challenges (“ behaviour that is of such intensity, frequency or duration as to threaten the quality of life and/or the physical safety of the individual or others and is likely to lead to responses that are restrictive, aversive or result in exclusion”[10]

) is often the primary reason for the high rate of antipsychotic prescribing in PwLD[11],[12],[13]

.

In the prescribing observatory for mental health, the Royal College of Psychiatrists — the professional body responsible for psychiatrists — highlights in a supplementary audit report that the indication for prescribing an antipsychotic was less likely to be a psychotic illness and more likely to be aggressive or self-harming behaviour[14]

.

Harmful effects of antipsychotics in PwLD

Evidence suggests that PwLD have a shorter life expectancy, poorer health outcomes and reduced access to healthcare compared with the general population[15],[16]

. Antipsychotic medication, particularly atypical antipsychotics, is associated with increased risk of metabolic syndrome (a cluster of risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease, including insulin resistance, hypertension, cholesterol abnormalities, obesity and increased risk of clotting)[17]

. The impact of these harmful effects can be further exacerbated by poor diet, lack of exercise and cigarette smoking.

Cardiovascular risk should be assessed prior to prescribing antipsychotics; this may include a baseline ECG. As antipsychotics can cause prolongation of QT interval, therefore, the addition of other drugs that increase QT interval can be an additional risk factor[18]

. All PwLD are entitled to an annual physical health check at their GP surgery where cardiovascular risk can be assessed.

Antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal side effects (EPSEs) appear to occur more frequently in PwLD. It has been suggested that this may be related to underlying brain pathology[19]

. Similarly, the propensity of antipsychotics to lower seizure threshold[14]

may be of concern because epilepsy is more common in PwLD than in the general population[20],[21]

. Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinaemia can affect the menstrual cycle and lead to amenorrhoea, cause sexual side effects and result in decreased bone mineral density.

Consequently, the harmful effects of antipsychotics in PwLD are a significant concern because they are often used long term without adequate review and poor physical health monitoring[1],[3],

[4],

[5],[9]

. Using these medicines is associated with both short and long-term adverse effects, such as fatigue and metabolic complications, coupled with the fact that they can be difficult to withdraw, even though there is no clear evidence for their effectiveness[22]

.

Current prescribing guidance on antipsychotics in PwLD

Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), England’s health technology assessment body, outlines recommendations for the use of antipsychotics in PwLD (See Box 1: ‘NICE guideline NG 11’). It suggests that prescribing these medicines for longer than six weeks would be considered “long-term”. The best evidence is for the use of risperidone at a low dose of 0.5–2mg[23]

.

Box 1: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline NG 11. Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges

The NICE NG11 guideline recommends that antipsychotics should only be considered:

- if psychological or other interventions alone do not produce change within an agreed time;

- treatment for any coexisting mental or physical health problem has not led to a reduction in the behaviour; and/or

- the risk to the person or others is very severe.

The NICE NG 11 guideline advises that antipsychotic medication should initially be prescribed and monitored by a specialist who should:

- decide how to measure effectiveness;

- monitor side effects;

- review side effects and effectiveness after 3–4 weeks;

- stop prescription after six weeks if there is no evidence of benefit; and

- document the reason for prescribing, length of treatment and strategy for reviewing medication.

Source: NICE guideline NG11. Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges. Published May 2015.

Review, reduction and withdrawal of antipsychotics in PwLD

The Stopping Over-Medication of People with a Learning Disability (STOMPwLD) pledge was recently signed by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, the Royal College of Nursing, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, the Royal College of GPs, the British Psychological Society and NHS England. Its goal is to improve the quality of life of PwLD by reducing the potential harm of inappropriate psychotropic drugs that may be used as a “chemical restraint” to control challenging behaviour in place of other more appropriate treatment options[24]

.

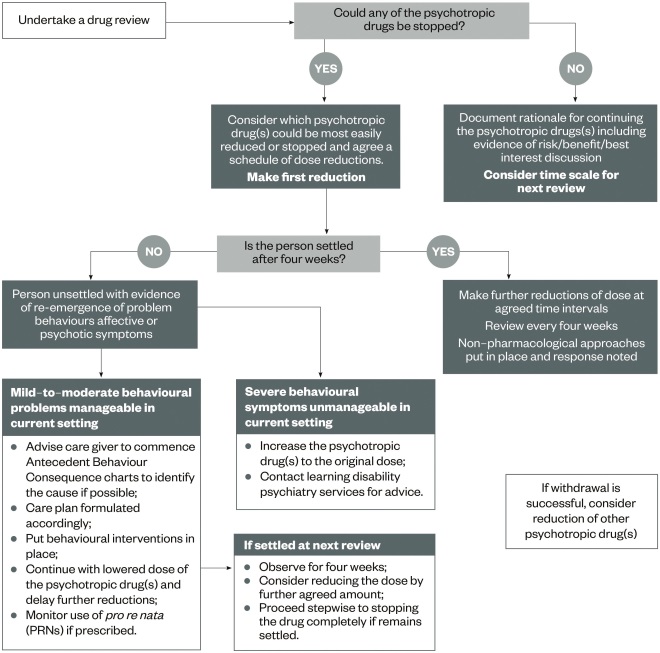

This presents an ideal opportunity for pharmacists and healthcare professionals to perform regular, patient-centred reviews of psychotropic medication prescribing in PwLD. ‘Figure 1: Stopping Over-Medication of People with Learning Disabilities (STOMPwLD)’ displays an algorithm for the review, reduction or stopping of psychotropic medication in PwLD.

Figure 1: Stopping Over-Medication of People with Learning Disabilities (STOMPwLD) 2016

Source: Reproduced with permission from NHS England

Algorithm for the review, reduction or stopping of psychotropic medication in people with learning disabilities (PwLD).

Pharmacists and healthcare professionals involved in the review and planned withdrawal of antipsychotics in PwLD should be aware of the possible complications. Published evidence is primarily based on the withdrawal of antipsychotic medication in psychotic illness, where stopping an antipsychotic is associated with three main risks: relapse; withdrawal psychosis; and withdrawal symptoms, such as insomnia and cholinergic rebound (e.g. headache, restlessness, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea)[25],[26]

. Withdrawing medication slowly reduces these risks; however, length of time to withdraw may depend on the dose, half-life and length of exposure of the medicine.

One of the clinical drivers in reducing antipsychotics in PwLD relates to over-sedation. This is because over-sedated PwLD do not require as much stimulation or structured activities as those who are more alert and able to engage in activities. Therefore, carers, support workers, families and social workers need to ensure that an appropriate programme of social activities is in place following the withdrawal of antipsychotics. Withdrawing an antipsychotic may also impact on nighttime sleeping, therefore, sleep hygiene measures should be reinforced to PwLD and carers[27]

. Pharmacists and healthcare professionals should remain vigilant to the increased prescribing or use of pro re nata (PRN) and regular hypnotics (e.g. temazepam and zopiclone).

Upon withdrawal, antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinaemia may improve, which may lead to resolution of ammenorhea and infertility[25]

. Therefore, it is imperative that, where appropriate, women of childbearing age are given contraceptive advice and signposted to local services or a GP surgery. In addition, in women who experience amenorrhoea, PwLD and their carers should be alerted that menstrual periods could return.

The causes of behaviour that challenges in PwLD may often be attributed to psychological, social and environmental causes, and frustration over the inability to communicate. Consequently, consideration for medical reasons for behaviour that challenges should also be explored and treated rather than commencing antipsychotic medication. Examples of these include:

- Infection or fever – treat the infection, antipyretic for fever;

- Uncontrolled pain – manage analgesia appropriately;

- Delirium;

- Hormone disturbance (menstrual cycle, peri and menopausal symptoms) – consider recommended treatment;

- Interictal/postictal psychosis in epilepsy – improve the medical management of epilepsy;

- Hyperglycaemia – dietary advice and medical management.

Following the case of Montgomery versus Lanarkshire health board[28]

and the implementation of the accessible information standard[29]

, it is imperative that PwLD, their families and carers are given appropriate information to make informed choices about their treatment[29]

. Optimising consultations with a PwLD is beyond the scope of this article; however, there are resources currently in development that could support pharmacists and healthcare professionals in this matter (e.g. the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education [CPPE] is currently developing an open learning package on learning disability, due to launch in late 2016).

Where appropriate, pharmacists and healthcare professionals should consider initiating a conversation with PwLD or their carers on the use of antipsychotics (see Box 2: ‘Tips on how to start a conversation around possible withdrawal of antipsychotics in PwLD’ and Box 3: ‘Alternatives to antipsychotics’).

Box 2: Tips on how to start a conversation around possible withdrawal of antipsychotics in people with learning disabilities (PwLD)

What

- Review continued need for prescription of antipsychotic.

Why

- Some people take medicines that they no longer require;

- Take care not to “demonise” antipsychotics – be mindful that a trial reduction of dose or complete withdrawal may not be permanent and antipsychotics may have to be restarted or dose increased especially after a diagnosis review;

- Discuss alternative options to antipsychotics (see Box 3: ‘Alternatives to antipsychotics’).

Who?

- GP or psychiatrist.

When?

- For a PwLD who has remained stable on medication, the concept of reduction may be daunting. Choose a suitable time and discuss the time frame.

How?

- Involvement and engagement of PwLD, carers, family and nurses. For some PwLD there is considerable pressure from carers and families for doctors to prescribe. In other situations, following the publication of articles in national newspapers, there may be pressure to stop medication.

Box 3: Alternatives to antipsychotics

- Positive behaviour programmes available through The Centre for the Advancement of Positive Behaviour Support (CAPBS), which were created to develop the knowledge, understanding and skills in the learning disability sector around positive behaviour support;

- The Challenging Behaviour Foundation provides support for both professionals and families;

- Optimisation of environment;

- Psychological therapies;

- Examination of addressing the triggers that cause challenging behaviour.

Sources: Bild. The Centre for the Advancement of Positive Behaviour Support. Available at: http://www.bild.org.uk/our-services/positive-behaviour-support/capbs/ (accessed September 2016); and the Challenging Behaviour Foundation. Available at: http://www.challengingbehaviour.org.uk/ (accessed September 2016)

Initiatives for improving education of pharmacists and healthcare professionals in reducing antipsychotic prescribing in PwLD

Experience of the Hertfordshire Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust

Easy-read leaflets for PwLD on several wide-ranging topics (e.g. off-label medicines use, maintaining bone health) have been developed by the Hertfordshire Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust (HPFT) and material focusing on PwLD undergoing withdrawal of psychotropic medicines is currently under development. All HPFT learning materials have been co-designed with its learning disability patient experience group.

In addition, the HPFT pharmacy team has been involved with providing education and training to psychiatrists about how to safely and effectively reduce antipsychotic medication. However, as a considerable number of PwLD are prescribed antipsychotics in primary care, it is likely that medication review, reduction and withdrawal will be conducted by GPs. Within the local health economy in Hertfordshire, a working group that is focusing on improving the use of medicines for PwLD has been established. The group includes local GPs, HPFT psychiatrists, a HPFT specialist mental health pharmacist, a community learning disability nurse from the local authority, a local clinical commissioning group pharmacist and commissioners.

Other initiatives

There are freely available, easy-read medication leaflets for PwLD from the University of Birmingham[30]

and the Elfrida Society[31]

. However, it must be noted that these materials have not been reviewed for some time and should be used with caution.

Box 4: Implications for pharmacists

- Optimising consultations with people with learning difficulties (PwLD), carers and families;

- Prompting a review of antipsychotic medication;

- Monitoring efficacy and prompting another medication review when appropriate;

- Monitoring and advising on the impact of short-term and long-term side effects of antipsychotics;

- Considering how to manage the withdrawal of antipsychotics;

- Considering how to manage the symptoms and effects of antipsychotic withdrawal;

- Being alert to physical health medication prescribed to counteract adverse effects that may no longer be required;

- Being alert to effects of physical health medication and medical conditions causing adverse behaviours (e.g. hyperglycaemia);

- Alert to an increase in prescribing, dispensing and administration of other psychotropic medicines as antipsychotics are withdrawn (e.g. hypnotics);

- Vital role in providing advice to healthcare professionals;

- Contributing towards making healthcare more accessible to PwLD.

There is a great drive to reduce the inappropriate prescribing of antipsychotics and other psychotropic drugs in PwLD from the DH, NHS England and professional health bodies. Pharmacists are suitably placed to contribute to this agenda (see Box 4: ‘Implications for pharmacists’).

Danielle Adams is principal clinical pharmacist andChetan Shah is chief pharmacist, Hertfordshire Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust.

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure:

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. No writing assistance was utilised in the production of this manuscript.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

Health inequalities

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s policy on health inequalities was drawn up in January 2023 following a presentation by Michael Marmot, director of the Institute for Health Equity, at the RPS annual conference in November 2022. The presentation highlighted the stark health inequalities across Britain.

While community pharmacies are most frequently located in areas of high deprivation, people living in these areas do not access the full range of services that are available. To mitigate this, the policy calls on pharmacies to not only think about the services it provides but also how it provides them by considering three actions:

- Deepening understanding of health inequalities

- This means developing an insight into the demographics of the population served by pharmacies using population health statistics and by engaging with patients directly through local community or faith groups.

- Understanding and improving pharmacy culture

- This calls on the whole pharmacy team to create a welcoming culture for all patients, empowering them to take an active role in their own care, and improving communication skills within the team and with patients.

- Improving structural barriers

- This calls for improving accessibility of patient information resources and incorporating health inequalities into pharmacy training and education to tackle wider barriers to care.

References

[1] Department of Health. Transforming care: a national response to Winterbourne. 2012. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213215/final-report.pdf (accessed September 2016)

[2] Emerson E & Heslop P. A working definition of learning disabilities. Department of Health and Learning Disabilities Observatory. Available at: https://www.improvinghealthandlives.org.uk/uploads/doc/vid_7446_2010-01WorkingDefinition.pdf (accessed September 2016)

[3] Public Health England. Prescribing of psychotropic drugs to people with learning disabilities and/or autism by general practitioners in England. Available at: http://www.nhsiq.nhs.uk/media/2671659/nhsiq_winterbourne_medicines.pdf (accessed September 2016)

[4] NHS Improving Quality. Winterbourne Medicines Programme Report. 2015. Available at: http://www.nhsiq.nhs.uk/winterbourne (accessed September 2016)

[5] NHS England. The use of medicines in people with learning disabilities. Letter to healthcare professionals from Keith Ridge, Chief Pharmaceutical Officer and Dr Dominic Slowie, National clinical director for learning disability. 2015.

[6] Emerson E & Baines S. Health inequalities and people with learning disabilities in the UK 2010. Department of Health and Learning Disabilities Observatory. Available at: http://www.improvinghealthandlives.org.uk/uploads/doc/vid_7479_IHaL2010-3HealthInequality2010.pdf (accessed September 2016)

[7] Deb S, Thomas M, Bright C. Mental disorder in adults with intellectual disability: prevalence of functional psychiatric illness among a community. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2001:45;495–505. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2001.00374.x

[8] Cooper S-A, Smiley E, Morrison J et al. Mental ill-health in adults with intellectual disabilities: prevalence and associated factors. Br J Psychiatry 2007:190; 27–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022483

[9] Sheehan R, Hassiotis A, Walters K et al. Mental illness, challenging behaviour, and psychotropic drug prescribing in people with intellectual disability: UK population based cohort study. BMJ 2015;351:h4326. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4326

[10] Report from the Faculties of Intellectual Disability of the Royal College of Psychiatrists and British Psychological Society. April 2016. Available at: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/FR_ID_08.pdf (accessed September 2016)

[11] NICE [QS101] published date October 2015. Learning Disabilities: challenging behaviour. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs101 (accessed September 2016)

[12] Deb S, Sohanpal SK, Soni R et al. The effectiveness of antipsychotic medication in the management of behaviour problems in adults with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabilit Res. 2007;51(Pt 10):766–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00950.x

[13] University of Hertfordshire. Intellectual disability and health. The use of medications for the management of problem behaviours in adults who have intellectual disabilities. Available at: http://www.intellectualdisability.info/mental-health/articles/the-use-of-medications-for-the-management-of-problem-behaviours-in-adults-who-have-intellectual-disabilities (accessed September 2016)

[14] Prescribing Observatory for Mental Health 2015. Topic 9c. Supplementary audit report. Antipsychotic prescribing in people with learning disabilities CCQI2013.

[15] MENCAP. Death by indifference. Available at: https://www.mencap.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2008-03/DBIreport.pdf (accessed September 2016)

[16] Independent review of deaths of people with a learning disability or mental health problem in contact with Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust from April 2011 to March 2015. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/south/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2015/12/mazars-rep.pdf (accessed September 2016)

[17] NICE. NICE guidelines [PH46] Published July 2013. BMI: Preventing ill-health and premature death in black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph46/chapter/6-Glossary#metabolic-syndrome (accessed September 2016)

[18] QT interval and drug therapy. DTB 2016;54;33–36. doi:10.1136/dtb.2016.3.0390

[19] Bhaumik S, Kumar Gangadharan S et al. The Frith prescribing guidelines for people with intellectual disability. 3rd Ed. 2015. Wiley.

[20] de Boer HM, Mula M & Sander JW. The global burden and stigma of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12:540–546. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.12.019

[21] NICE. Clinical guideline [CG137]. Published date 2012. The epilepsies: the diagnosis and management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg137 (accessed October 2016)

[22] De Kuijper G, Evenhuis H, Minderaa RBet al. Effects of controlled discontinuation of long-term used antipsychotics for behavioural symptoms in individuals with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res 2014;58:71–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01631.x

[23] NICE. NICE guidelines [NG11]. Published May 2015. Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng11 (accessed September 2016)

[24] NHS England. Doctors urged to help stop ‘chemical restraint’ as leading health professionals sign joint pledge. June 2016. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/2016/06/over-medication-pledge/ (accessed September 2016)

[25] Taylor D, Paton C & Kapur S. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. 12th Ed. 2015. Wiley.

[26] Bazire S. Psychotropic drug directory 2016. Lloyd-Reinhold Communications.

[27] NHS Choices. Insomnia. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Insomnia/Pages/Prevention.aspx (accessed September 2016)

[28] Update on the UK law on consent. BMJ 2015;350:h1481. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1481

[29] NHS England. Accessible information standard. Making health and social care information accessible. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/patients/accessibleinfo/ (accessed September 2016)

[30] University of Birmingham. Medicine information – learning disabilities medication guideline. Available at: http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/activity/ld-medication-guide/downloads/medicine-information.aspx (accessed September 2016)

[31] The Elfrida Society. Easy to read medication information for people with learning difficulties. Available at: http://www.elfrida.com/medication-leaflets.htm (accessed September 2016)