Shutterstock.com

After reading this article you should be able to:

- Understand the emotional, psychological and social factors that contribute to self-harming behaviour in children and young people, and the underlying causes;

- Be aware of the critical need for a comprehensive support system tailored to the unique needs of children who self-harm;

- Recognise the role of pharmacists in conducting medication-related risk assessments for children at risk of self-harm and how pharmacists can play a pivotal role by ensuring the safe dispensing of medication and provision of appropriate advice.

Introduction

Self-harm is characterised by deliberate self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of the presence of suicidal intent or other motivating factors. It is a significant concern in young people in the UK, often leading to hospital admissions1,2. Several studies have reported that around 13–14% of young people aged under 18 years in the UK acknowledge engaging in self-harm3–5. In 2018, results from a UK study that used data from the Office for National Statistics relating to suicide and self-harm in young people aged 12–17 years, carried out by Geulayov et al., showed a higher number of females than males self-harming (78% vs 51%), and that hospital presentation occurred in 9% of of adolescent patients after an episode of self-harm, most of which related to self-poisoning (71%; n=849)6.

In 2024, the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities reported 32,624 hospital admissions resulting from self-harm in children and young people aged 10–24 years across England in 2022/20237.

Research has focused on understanding the characteristics of those who seek medical help after self-harm and there’s a notable scarcity of comprehensive studies examining self-harming behaviours among adolescents, posing a challenge because most young people who self-harm do not present to clinical services3,8. An international comparative study of 30,532 pupils aged 14-17 years found that nearly half (48.4%; n=803) did not receive any help following an incident of self-harm.

There is variability in estimates of global prevalence of self-harm in children and young people. In 2014, results from a meta-analysis revealed a wide-ranging prevalence of deliberate self-harm in individuals aged 12–20 years, with rates spanning from 5.5% to 30.7%9. The underlying factors contributing to this considerable variability remain unclear but could stem from intercultural disparities or methodological variations across different studies. Notably, many investigations on self-harm exhibit a bias towards Western countries, findings of which are not always transferable to other cultures10.

Adolescence and early adulthood (defined as ages 10–19 years) are particularly vulnerable periods and, according to the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, suicide is one of the leading causes of death during this period11,12. Repeated self-harm is strongly linked to an increased risk of future suicide13. It is recommended that healthcare professionals use each encounter with children and young people as opportunities to enquire about mental wellbeing, recognise early signs of poor mental health and be alert to potential disclosures, offering appropriate mental health support and follow-up12. This is especially important for young people presenting with indications of self-harm12.

Self-harm is an escalating issue among children and adolescents aged 10–14 years in the UK14. While instances of self-harm are often low risk and transient, in many cases it can become life threatening, and some individuals continue to self-harm into adulthood15. Self-harm can serve as a poignant indicator of severe emotional distress and is a leading cause of death for individuals aged 5–19 years globally4,16.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on ‘Self-harm: assessment, management and preventing recurrence’, published in 2022, recognises the indispensable role that pharmacists play in supporting individuals at risk, underscoring the need for multidisciplinary collaboration to ensure the wellbeing of this vulnerable group17.

This article explores some of the reasons for self-harming behaviour in children and young people, discusses interventions, and advocates for a holistic approach that transcends pharmaceutical expertise, emphasising the importance of compassionate understanding when addressing the emotional and psychological complexities faced by these young individuals.

It also considers the role that pharmacists play when conducting medication-related risk assessments, facilitating safe medication practices, and actively participating in the identification, support and appropriate referrals of children and young people experiencing self-harm.

Reasons for self-harming in children and young people

Self-harm is a complex issue and there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ explanation for why children and adolescents engage in this behaviour. It is essential that healthcare professionals take a holistic approach to understanding and treating self-harm, considering the individual’s unique circumstances and needs.

Self-harm is often classified as a symptom of other common mental illnesses, such as depression, anxiety and personality disorder, but researchers have theorised that emotional dysregulation, deficits in reward and consequence processing and/or atypical processing of information regarding the self could explain why some individuals self-harm18.

For children and young people, a major brain structure thought to change functionally in response to childhood experiences is the amygdala, which can become hyper-reactive owing to prolonged stress. This hyperactivation is linked to distress and difficulty regulating heightened emotions. Individuals with emotional dysregulation and a predisposition to self-harm may use it to cope with or reduce painful emotional responses19.

Bailey et al. have proposed a continuum of self-harm behaviours, which include responses to psychosocial stressors from developmental milestones, self-harm with clinical symptoms including anxiety and depression, and self-harm indicating a desire to end consciousness20. Findings suggest that a nuanced understanding can aid GPs in responding to young people’s self-harm and inform signposting and treatment decisions (see Figure 1)20.

Figure 1: Continuum of self-harm behaviour in young people

The Pharmaceutical Journal

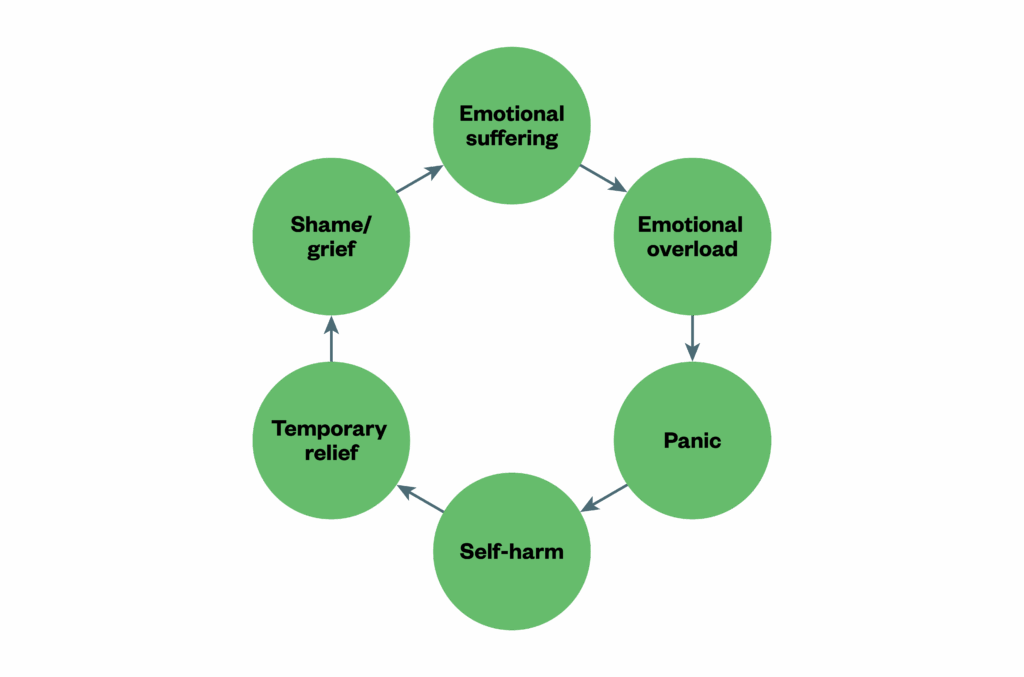

When individuals engage in self-harm, they may initially experience a sense of control or temporary relief from intense emotions and, over time, this behaviour can become habitual or even addictive, perpetuating a vicious cycle of self-harm, as seen in Figure 221.

Figure 2: The cycle of self-harm

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Self-harming poses significant risks for children and young people, particularly with regards to increased mortality. Children who have self-harmed are 9 times more likely to die unnaturally during follow-up than unaffected peers and 17 times more likely to die from suicide22. Fatal acute alcohol and/or drug poisonings highlight the importance of effective interagency collaboration to enhance safety and future mental wellbeing for distressed young people.

Management

Children and young people are more likely to reduce self-harming behaviours when the underlying stressors and triggers are addressed. Education and harm minimisation strategies, especially for adolescents with repetitive patterns of self-harm, can be important tools23. Many adolescents may be unaware of the potential for self-harm to cause serious damage, morbidity or even death.

Prevention efforts can include teaching healthier coping mechanisms (e.g. distraction techniques such as responding to a series of questions that help identify negative feelings)24. It can also be effective to identify which self-harming behaviour would be used as a coping strategy, before advising that the patient does something safer that would elicit a similar sensation (e.g. sucking on a lemon to get a sharp sensation when angry and thinking about cutting)24.

Scientific evidence on pharmacological interventions for reducing repetitive deliberate self-harm in children and adolescents is limited. While antidepressants may be offered following episodes of self-harm, psychotropic medication is generally only considered helpful if used to treat underlying psychiatric conditions when psychological therapies have been unsuccessful22.

The role of pharmacists

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s vision for pharmacists to be more involved in mental health teams, especially in child and adolescent mental health services, aligns with the crucial role they can play in addressing the self-harm cycle in young people25. As outlined in the NICE guidelines for self-harm, pharmacists can contribute through early identification and informal risk assessment in primary care settings, managing complex medication queries, providing prescribing advice on drug treatments, and running medication review clinics17.

This multifaceted support from pharmacists, integrated within a comprehensive, compassionate approach in collaboration with mental health services, can help interrupt the habitual and cyclical nature of self-harm in children and young people.

1. Early identification:

Children may acquire tools or substances for self-harm discreetly. Pharmacists can be trained to recognise suspicious purchase patterns or behaviours, just as they have been trained to identify potential substance misuse26. For instance, community pharmacists and primary care pharmacists can risk assess family members when high-risk medication with very low therapeutic index are being dispensed.

2. Education:

Pharmacists are well-positioned to educate the community, parents and teachers about the signs of self-harm in children. Workshops or information sessions can be organised in community settings to spread awareness and prevention strategies27.

3. Referral and collaboration:

By fostering connections with local mental health professionals, pharmacists can ensure swift referral of identified children to appropriate care. With collaboration between local mental health services and community pharmacists, agreements can be made for information sharing so that named pharmacists of young people at risk of self-harm can be made aware of any safety plans in place for such young persons.

The Department of Health and Social Care’s ‘Consensus statement for information sharing and suicide prevention‘ states: “Information can be shared about a child or young person for the purposes of keeping them safe. In practice, this means that practitioners should disclose information to an appropriate person or authority if this is necessary to protect the child or young person from risk of death or serious harm. A decision can be made to share such information with the family and friends where necessary”28.

4. Risk assessments

When pharmacists suspect that individuals may be at risk of self-harming behaviours, they could carry out short risk assessments, see Box.

Box: Quick risk assessment

- Check historical risk factors (e.g. potential lethality of previous self-harm episodes, previous triggers and attitude to self-harm);

- Check for current risk factors (e.g. suicidal ideation, self-harming behaviours, mood instability and impulsivity);

- Refer immediately if previous self-harming attempt lethal or current self-harming behaviour or ideation lethal.

While it is not possible to completely remove the risks that medicines may have in young people with a history of self-harm, pharmacists can advise on precautions that may need to be put in place to reduce risks.

Many self-harming episodes involve the misuse of over-the-counter (OTC) or prescription medications. By ensuring appropriate dispensing, implementing safeguard measures and monitoring usage patterns, pharmacists can reduce the risk of medication-related self-harm29.

A potential way of mitigating risk is reducing the quantity of medicines supplied, but there are also other things to consider in collaboration with the patient that may include:

- Using modified release preparations that have a delayed and reduced peak in overdose;

- Using long-acting injections (depot) antipsychotics in those prescribed oral forms of these, where there are frequent overdoses (this is off-licence for children and young people but can be considered as part of a risk–benefit analysis);

- Working collaboratively with the multidisciplinary team and other professionals involved in the young person’s care30.

Of note is the need to always use the lowest effective dose, avoid polypharmacy where possible and consider the negative effects of unmanaged conditions (physical or mental health) or side effects that can increase the risk of suicide30.

Table 1 depicts some points to consider when risk assessing medication prescribed to a young person at risk of harming themselves20,31–42.

5. Counselling and crisis intervention:

Pharmacists with specialised training, including identifying and managing trauma and lived experiences, may be able to offer immediate counselling to children in distress, potentially averting a self-harm episode31. Some examples of training and resources that can support pharmacists to carry out consultations with children and young people at risk include the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education’s module on ‘Consulting with children and young people‘ or the ‘Mental health improvement and prevention of self-harm and suicide‘, available from NHS Education for Scotland.

Pharmacists without specialised training can help children and young people at risk of self-harm by:

- Creating links with local child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS) services and understanding local pathways for urgent referrals;

- Engaging with charities and organisations that provide support for children and young people who self-harm and, where appropriate, link affected families with these organisations;

- Improving communication skills to facilitate conversations during consultation with young people suspected of self-harming.

The case study below highlights the need for integrated care involving local child and adolescent mental services, young people and their families, and local community pharmacists. NICE guidance advocates using shared decision-making to discuss limiting quantity of medicines supplied to people with a history of self-harm17.

Case study

A 16-year-old with a history of trauma who has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder is under the care of the community CAMHS. She is regularly seen by her consultant psychiatrist and reviewed at multidisciplinary team meetings. Her mental illness causes unpredictable, variable risk of serious self-harm and suicide. Owing to this risk, a safety plan is agreed whereby her parents have responsibility for her prescribed medication.

When her consultant psychiatrist makes changes to her medication, the girl requests that her parents not be told about this change. Her psychiatrist makes the judgement that she is able to make this decision for herself so does not inform the parents and gives her a prescription for an anticonvulsant medication and lorazepam with a 28-day duration.

The girl does not inform her parents that she has received a new prescription and has the medication dispensed at her regular pharmacy. At the community pharmacy, she is assumed competent to collect her own prescription and is also allowed to pick up some older prescription medication that had not been collected earlier.

The girl subsequently conceals these medicines in her room and a few days later, after deciding to go to bed early, takes a large overdose of the prescription medications. Her mother checks on her before going to bed herself and finds her unresponsive and calls for an ambulance.

Ways this incident could have been prevented

- The dispensing of lorazepam to a patient aged 16 years should have been a red flag to warrant a risk assessment before handing out medication to a client, especially if the patient presented alone at community pharmacy;

- If they were aware of self-harm concerns, the pharmacist could have limited supply and prescribed smaller amounts at a time;

- Facilitation of information sharing between CAMHS services and the patient’s community pharmacy;

- Access to summary care records (SCR) by community pharmacists would support decision-making when dispensing medication to children and young people. In this case, the pharmacist did not have access to the SCR and therefore could not check the patient’s history.

There should be local protocols that ensure pharmacies that are regularly used by patients aged 16–17 years and who are at risk of, or have a history of, self-harm, are advised of relevant care plans put in place by CAMHS, where appropriate. Pharmacy staff should be trained on assessing medication-related needs and safety of young people who have self-harmed and be aware of warning signs relating to self-harm, such as identifying those who have access to large amounts of medicines17.

Best practice points

- Pharmacists can be more vigilant, observing and questioning suspicious purchases, patterns or behaviours;

- Pharmacists can educate the public, including parents and caregivers, about the signs of self-harm, the self-harm cycle, the importance of seeking professional help early, and potential for harmful use of medication that can be purchased over the counter;

- Community pharmacists can collaborate with mental health teams, including child and adolescent mental health services, to ensure a coordinated and comprehensive approach to supporting individuals and families affected by self-harm;

- Pharmacists can ensure swift referral of identified children to appropriate care;

- Pharmacists can support with conducting medication-related risk assessments;

- Pharmacists in all sectors can help provide resources and guidance to families on healthy coping strategies, signpost to support services, and with appropriate training, suggest ways to create a nurturing environment for children and young people struggling with self-harm;

- Pharmacists should be able to carry out a quick risk assessment of individuals presenting with self-harming behaviours and refer for immediate support where needed.

Conclusion

The increasing incidence of self-harm among children and adolescents is a pressing public health concern that requires consistent, ongoing attention. This article has explored the multifactorial reasons behind self-harming behaviours, highlighting the profound emotional distress that often accompanies such actions. While many cases may appear low-risk and transient, the potential for escalation into life-threatening situations emphasises the need for vigilant and compassionate intervention.

To effectively address the complexities of self-harm, it is vital to establish integrated care pathways that connect healthcare professionals in primary and secondary care services. Such pathways facilitate communication and collaboration, ensuring that pharmacists can actively engage in medication-related risk assessments, promote safe medication practices, and offer empathetic support. By doing so, they can play a pivotal role in the identification and referral of children and adolescents at risk of self-harm.

As we advance in our understanding of this critical issue, it is imperative to recognise and empower pharmacists as integral members of the care team. Their involvement not only enhances the overall quality of care but also fosters a supportive environment that prioritises the mental and emotional wellbeing of young individuals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nicola Greenhalgh, deputy chief pharmacist of Essex Partnership University Foundation Trust, for her help with developing Table 1.

- 1.O’Loughlin S, Sherwood J. A 20-year review of trends in deliberate self-harm in a British town, 1981–2000. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol. 2005;40(6):446-453. doi:10.1007/s00127-005-0912-3

- 2.Schmidtke A, Bille‐Brahe U, Deleo D, et al. Attempted suicide in Europe: rates, trend.S and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989–1992. Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(5):327-338. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10656.x

- 3.O’Connor RC, Rasmussen S, Miles J, Hawton K. Self-harm in adolescents: self-report survey in schools in Scotland. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(1):68-72. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.047704

- 4.Hawton K. By their own young hand. BMJ. 1992;304(6833):1000-1000. doi:10.1136/bmj.304.6833.1000

- 5.O׳Connor RC, Rasmussen S, Hawton K. Adolescent self-harm: A school-based study in Northern Ireland. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;159:46-52. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.015

- 6.Geulayov G, Casey D, McDonald KC, et al. Incidence of suicide, hospital-presenting non-fatal self-harm, and community-occurring non-fatal self-harm in adolescents in England (the iceberg model of self-harm): a retrospective study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(2):167-174. doi:10.1016/s2215-0366(17)30478-9

- 7.Public Health Profiles: Self Harm. Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. 2024. Accessed September 2025. https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/search/self%20harm

- 8.Ystgaard M, Arensman E, Hawton K, et al. Deliberate self‐harm in adolescents: Comparison between those who receive help following self‐harm and those who do not. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;32(4):875-891. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.010

- 9.Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ. Prevalence of Nonsuicidal Self‐Injury in Nonclinical Samples: Systematic Review, Meta‐Analysis and Meta‐Regression. Suicide & Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(3):273-303. doi:10.1111/sltb.12070

- 10.Muehlenkamp JJ, Claes L, Havertape L, Plener PL. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2012;6(1). doi:10.1186/1753-2000-6-10

- 11.Suicide worldwide in 2021: global health estimates. World Health Organization. May 2025. Accessed September 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240110069

- 12.State of Child Health in the UK. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2020. Accessed September 2025. https://stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk

- 13.Carroll R, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D. Hospital management of self-harm patients and risk of repetition: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;168:476-483. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.027

- 14.Griffin E, McMahon E, McNicholas F, Corcoran P, Perry IJ, Arensman E. Increasing rates of self-harm among children, adolescents and young adults: a 10-year national registry study 2007–2016. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(7):663-671. doi:10.1007/s00127-018-1522-1

- 15.Fox F, Stallard P, Cooney G. GPs role identifying young people who self-harm: a mixed methods study. FAMPRJ. Published online May 8, 2015:cmv031. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmv031

- 16.Liu L, Villavicencio F, Yeung D, et al. National, regional, and global causes of mortality in 5–19-year-olds from 2000 to 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2022;10(3):e337-e347. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(21)00566-0

- 17.Self-harm: assessment, management and preventing recurrence. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022. Accessed September 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng225

- 18.Pambianchi H, Whitlock J. Understanding the neurobiology of non-suicidal self-injury Information Brief Series, Cornell Research Program on SelfInjury and Recovery. Cornell University. 2019. Accessed September 2025. https://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/the-neurobiology-of-nssi.pdf

- 19.Plener PL, Bubalo N, Fladung AK, Ludolph AG, Lulé D. Prone to excitement: Adolescent females with non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) show altered cortical pattern to emotional and NSS-related material. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2012;203(2-3):146-152. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.12.012

- 20.Bailey D, Wright N, Kemp L. Self-harm in young people: a challenge for general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(665):542-543. doi:10.3399/bjgp17x693545

- 21.Young People and Self-harm. CHAD Research. 2019. Accessed September 2025. https://www.chadresearch.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CHAD-Young-People-and-Self-harm-final-report-Dec-2019.pdf

- 22.Morgan C, Webb RT, Carr MJ, et al. Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. BMJ. Published online October 18, 2017:j4351. doi:10.1136/bmj.j4351

- 23.King J, Cabarkapa S, Leow F. Adolescent self-harm: think before prescribing. Aust Prescr. 2019;42(3):90-92. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2019.023

- 24.Kilburn E, Whitlock J. Distraction techniques and alternative coping strategies. Cornell University. 2009. Accessed September 2025. https://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/distraction-techniques-pm-2.pdf

- 25.Improving care of people with mental health conditions: how pharmacists can help. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. October 2020. Accessed September 2025. https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Policy/Scottish%20Mental%20Health%20Policy%202020.pdf

- 26.Boyer EW. Management of Opioid Analgesic Overdose. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):146-155. doi:10.1056/nejmra1202561

- 27.Murphy E, Kapur N, Webb R, Cooper J. Risk assessment following self-harm: comparison of mental health nurses and psychiatrists. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;67(1):127-139. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05484.x

- 28.Consensus statement for information sharing and suicide prevention. Department of Health and Social Care. 2021. Accessed September 2025. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/consensus-statement-for-information-sharing-and-suicide-prevention

- 29.Gould MS, Marrocco FA, Hoagwood K, Kleinman M, Amakawa L, Altschuler E. Service Use by At-Risk Youths After School-Based Suicide Screening. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(12):1193-1201. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e3181bef6d5

- 30.Drug misuse prevention: targeted interventions. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2017. Accessed September 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng64/chapter/Recommendations

- 31.Miller M, Swanson SA, Azrael D, Pate V, Stürmer T. Antidepressant Dose, Age, and the Risk of Deliberate Self-harm. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):899. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1053

- 32.NEPTUNE (Novel Psychoactive Treatment: UK Network). Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust. Accessed September 2025. https://www.cnwl.nhs.uk/neptune

- 33.Chen Q, Sjolander A, Runeson B, D’Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H. Drug treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and suicidal behaviour: register based study. BMJ. 2014;348(jun18 18):g3769-g3769. doi:10.1136/bmj.g3769

- 34.Depression in children and young people: identification and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019. Accessed September 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng134

- 35.Taylor D, Barnes T, Young A. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry – The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines Series. 14th ed. Wiley Blackwell; 2021. Accessed September 2025. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/The+Maudsley+Prescribing+Guidelines+in+Psychiatry%2C+14th+Edition-p-9781119772231

- 36.ToxBase. ToxBase. Accessed September 2025. https://www.toxbase.org/

- 37.Chua KP, Brummett CM, Conti RM, Bohnert A. Association of Opioid Prescribing Patterns With Prescription Opioid Overdose in Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(2):141. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4878

- 38.Paracetamol for adults. NHS. Accessed September 2025. https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/paracetamol-for-adults/

- 39.Co-codamol for adults. NHS. Accessed September 2025. https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/co-codamol-for-adults/

- 40.Paracetamol overdose. BMJ Best Practice . 2023. Accessed September 2025. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/patient-leaflets/en-gb/html/1487843271809/Paracetamol%20overdose

- 41.Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: recognition and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2009. Accessed September 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg91/ifp/chapter/depression-and-long-term-physical-health-problems

- 42.Oladunjoye AF, Li E, Aneni K, Onigu-Otite E. Cannabis use disorder, suicide attempts, and self-harm among adolescents: A national inpatient study across the United States. Patel RS, ed. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(10):e0292922. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0292922