Jim West / Science Photo Library

Summary

Damage to the spine renders the enclosed nerves susceptible to injury. This article focuses on the necessary interventions that arise when structural changes to the spine impinge on nervous system function.

The rationale for surgical intervention is to improve the quality of life of patients who are experiencing radiculopathy (compression of nerve roots causing neuropathic pain) with symptoms unable to be medically controlled, or to prevent further deterioration from myelopathic symptoms, which include loss of dexterity (e.g. dropping things, numbness, tingling of hands), unsteadiness, clumsiness or numbness of feet, with patients often reporting that their legs ‘just won’t go’. When a patient demonstrates persistent or progressive signs and symptoms of myelopathy, such as weakness, gait instability, bladder or bowel dysfunction, then surgical decompression is indicated.

Cervical spine surgery is most commonly performed for myelopathy or radiculopathy and involves an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Surgery for cervical radiculopathy is performed to try to improve the radiating arm pain, whereas surgery performed for myelopathy is an attempt to prevent any further deterioration. Lumbar nerve root decompression generally involves microdiscectomy, where a microscope is brought in and the prolapsed disc material is removed, freeing up the compressed nerve root.

Patients undergoing lumber and cervical decompressive procedures can be admitted on the same day of surgery and may be discharged within 24 hours of surgery. Beyond short-term analgesia for operative site pain, most patients are unlikely to have significant changes to any regular chronically-prescribed drug therapy, however patients on antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulants will require special management. After spinal surgery, some patients may experience post-operative nausea and vomiting, spasm of back muscles and surgical site or neuropathic pain, all of which can be effectively managed with appropriate pharmacotherapy.

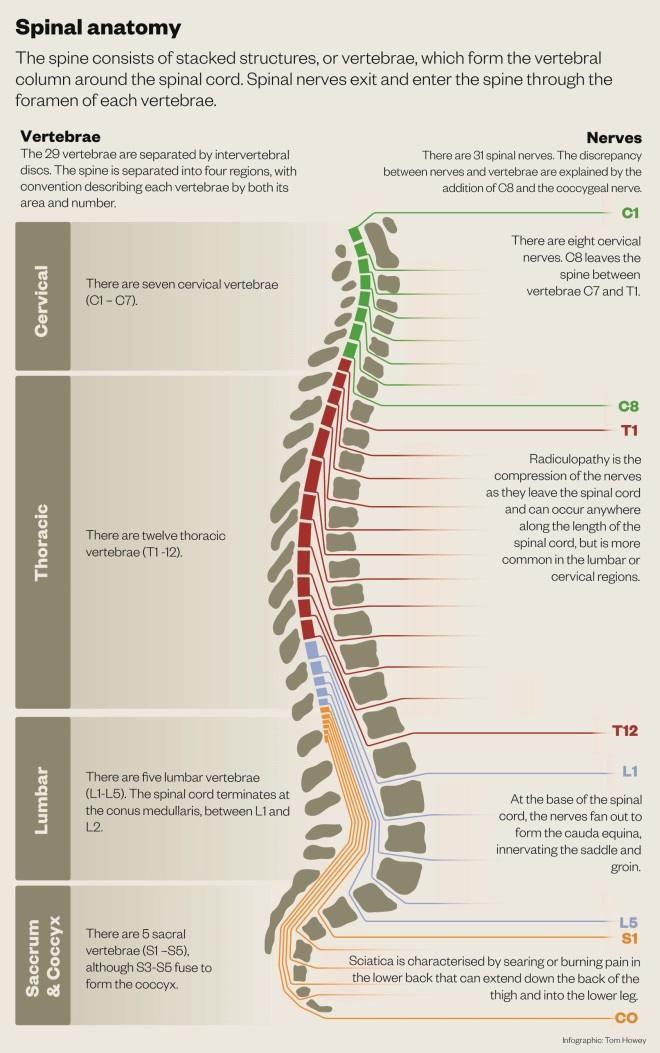

The spine consists of the spinal column and spinal cord, which have the essential function of forming part of the skeletal system, and forming the link between the brain and peripheral nervous system, respectively. The prevalence of lumbosacral radiculopathy (compression of nerve roots causing neuropathic pain) is estimated to be 3–5%[1]

and in 2010–2011 there were 236,801 finished consultant episodes within NHS England for all categories of spinal intervention[2]

. This article will outline the rationale for decompressive spinal surgery, which can be performed by neurosurgical and orthopaedic services, the pharmacological management of associated symptoms, and the peri-operative management of patients undergoing spinal surgery.

Source: spinalhub.com.au

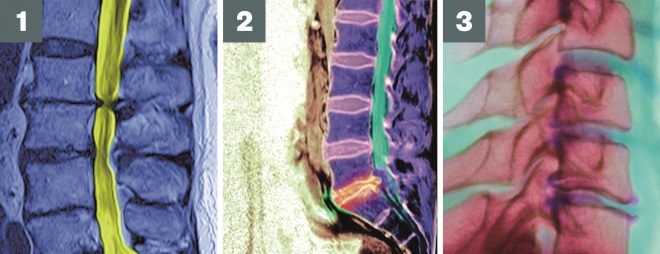

Photo guide: Spinal pathologies

Source: Science Photo Library

1) Myelopathy: Compression of the spinal cord resulting in neurological deficit. Symptoms include loss of dexterity, unsteadiness, clumsiness or numbness of feet.

2) Prolapsed intervertebral discs: Compression of the spinal nerves directly or indirectly through inflammation due to the prolapsed disc. More common in the lumbar spine.

3) Osteophyte formation: Osteophytes are radiographic markers of spinal degeneration (ageing). They represent an enlargement of the normal bony structure which impinge on nerves.

Radiculopathy, myelopathy and the rationale for surgery

Damage to the spine renders the enclosed nerves susceptible to injury. Acute traumatic, inflammatory and vascular damage to the spinal cord itself are outside of the scope of this article, which will instead concentrate on necessary interventions that arise when structural changes to the spine impinge on nervous system function. The spine is prone to ‘wear and tear’ and degenerative changes of ageing, such as osteophyte formation (bony spurs that subsequently impinge on nerves) and osteoarthritic changes[3]

. Prolapsed (slipped) intervertebral discs can also compress spinal nerves directly or indirectly through resultant inflammation. A prolapsed disc is more common in the lumbar spine, since this section is exposed to greater forces through physical activity, such as lifting[4]

(see ‘Spinal anatomy and pathologies’).

The rationale for surgical intervention is to improve quality of life for patients who are experiencing radiculopathy with symptoms that cannot be medically controlled[5]

, or to prevent further deterioration from myelopathic symptoms[6]

. However, the decision to proceed to surgery should be an individual one for the patient, made through informed consent and in receipt of the knowledge of the potential benefits and risks[7],

[8]

.

Myelopathy is compression of the spinal cord, generally without associated pain. Symptoms include loss of dexterity (e.g. dropping things, unsteadiness, clumsiness), numbness and tingling (paraesthesia) or loss of power.

When a patient demonstrates persistent or progressive signs and symptoms of myelopathy, such as weakness, gait instability, bladder or bowel dysfunction, surgical decompression is indicated[7]

.

Radiculopathy is compression of the nerves as they leave the spinal cord. Pressure on the nerve root causes neuropathic pain along the relevant dermatomal pathway and is usually described by the patient as a sharp or shooting pain. Weakness can occur if the nerve is sufficiently compressed. Sciatica is a lumbosacral radiculopathy characterised by ‘electric shock-type’ pain, or a searing or burning pain that originates in the lower back or buttock and can extend down the back of the thigh into the lower leg (see ‘Spinal anatomy and pathologies’).

The detailed treatment of neuropathic pain is beyond the scope of this article, but there are general national guidelines[9] that advocate amitriptyline, gabapentin, pregabalin and duloxetine as pharmacological treatment options. The general treatment principle with these drugs is to start at a low dose and titrate to the response of reduction in pain and/or the emergence of unacceptable side effects.

Low back pain may also be present, which is distinct from neuropathic pain, usually less severe, and can often be managed with paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or a weak opioid[10],

[11]

. Low dose tricyclic antidepressants[11]

, such as amitriptyline[12]

can also be offered for low back pain. Around 70–75% of patients undergoing lumbar surgery will experience a significant improvement in leg pain, 20–25% of patients achieve some pain relief, 5% have no pain relief at all and 1% experience worsening pain[8]

. Healthcare professionals should also be vigilant for red flag symptoms suggestive of cauda equina syndrome (see ‘Cauda equina syndrome: red flags’) and refer patients immediately for urgent investigation[13]

.

Cauda equina syndrome: red flags

Symptoms of bladder, bowel or sexual dysfunction, with perianal or ‘saddle’ numbness should alert suspicion to cauda equina syndrome.

Bladder symptoms:

- Problems with passing urine, including poor flow and reduced sensation;

- Urinary retention.

Bowel symptoms:

- Constipation or inability to stop a bowel movement;

- A loss of sensation when moving bowels.

Sexual function symptoms:

- In males, impotence or inability to ejaculate;

- Loss of sensation during intercourse.

Saddle anaesthesia:

- Loss of feeling or numbness in the saddle region, which can be noted by an inability to feel the toilet paper when wiping after a bowel motion.

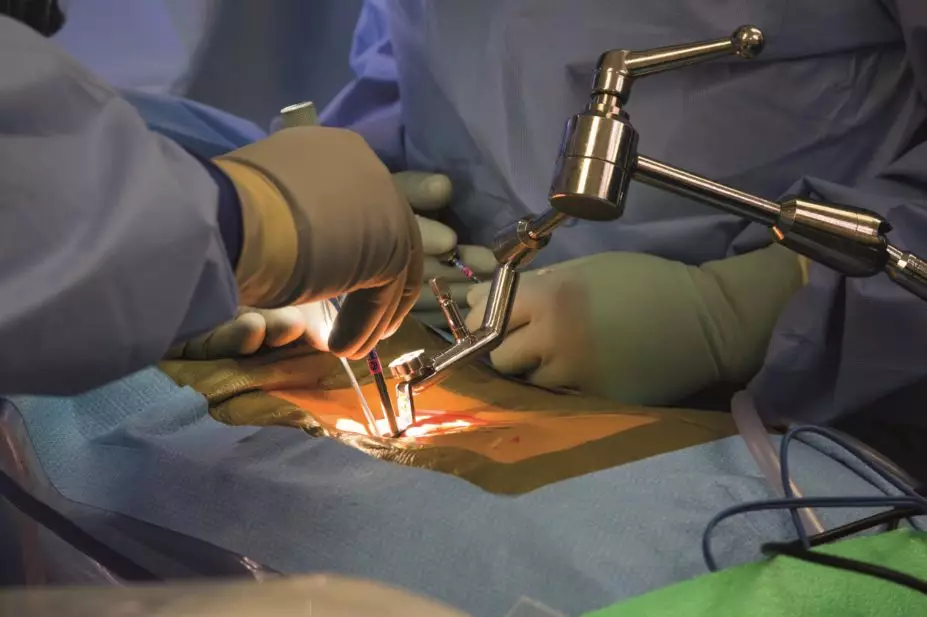

Surgical procedures

Cervical spine surgery is most commonly performed for myelopathy or radiculopathy and involves an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF). An ACDF is performed from the front of the neck, generally on the right side, following the natural corridor down to the front of the spine. The whole of the disc is removed, and a carbon fibre cage placed between the two cervical vertebrae, which fuses the two levels together. Risks of ACDF surgery include deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), dural tear/cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, nerve root injury, wound infection, spinal cord injury leading to paralysis and nerve injury leading to dysphagia and/or hoarse voice.

Surgery for cervical radiculopathy is performed to try and improve the radiating arm pain, whereas surgery performed for myelopathy is an attempt to prevent any further deterioration. Improvement in myelopathic symptoms is not guaranteed and it is difficult to predict which patients are likely to gain improvement in symptoms[7]

.

Lumbar nerve root decompression generally involves microdiscectomy, performed from the back, with the surgeon creating a corridor through the lamina on the affected side. A microscope is brought in and the prolapsed disc material is removed, freeing up the compressed nerve root. Risks of lumbar microdiscectomy surgery include DVT/PE, dural tear/CSF leak, nerve root injury, wound infection/discitis and injury to abdominal vessels, which lay on the front of the spine. Serious complications are uncommon.

Pharmaceutical care for the spinal surgery patient

Patients undergoing lumber and cervical decompressive procedures can be admitted on the same day of surgery and may be discharged within 24 hours. An assessment by a physiotherapist and by an occupational therapist is usually required to ensure that the patient is functionally safe for discharge. Therefore, spinal surgical wards can have a relatively fast rate of patient turnover and there is scope for pharmacy team involvement to facilitate the patient pathway and improve care.

Beyond short-term analgesia for operative site pain, most patients are unlikely to have significant changes to any regular chronically-prescribed drug therapy. There is also potential for the implementation of a system that utilises the patient’s own drugs.

Antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulants (aspirin, clopidogrel and warfarin, rivaroxaban and apixaban respectively), are stopped pre-operatively. There is paucity of evidence to guide the optimal safe timing to stop and re-start these treatments[14]

and there is likely to be variation between, and possibly within, surgical units. Anticoagulants should be bridged in accordance with local guidelines. An important pharmaceutical care intervention is to ensure there is a plan in place to re-initiate antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs post-operatively with appropriate monitoring, such as international normalized ratio (INR) checking for warfarin, and to ensure patients understand the plan at discharge. These issues can be identified through medicines reconciliation, particularly when enquiring about drugs that have been discontinued for surgery.

Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV), when it does occur, can be managed through local guidelines. Management and avoidance strategies for PONV have been previously reviewed[15]

.

Spasm of back muscles can occur post-operatively and can be treated with a short course, for example three days, of a low-dose benzodiazepine such as diazepam 2mg three times daily, as per the British National Formulary (BNF). It is unusual to require prolonged courses of benzodiazepine and such prescriptions should be queried with the surgical team, recommending regular review of ongoing need.

Surgical site pain can usually be managed with paracetamol. Escalation through the analgesic ladder rarely needs to go beyond weak opioids such as codeine, giving rise to the potential to utilise standardised analgesic pre-packs for these patients, under agreed protocols such as patient group directions, to facilitate the discharge process[16]

.

Neuropathic pain is usual following radiculopathy. A prognostic indication of post-surgical resolution of neuropathic pain may be provided from the pre-operative work up. Where neuropathic pain is relieved, consideration should be given to withdrawing anti-neuropathic pain agents. We offer no specific guidelines on how to withdraw but our practice is to suggest it is done relatively slowly, over at least one week for gabapentin and pregabalin, and longer for amitriptyline and duloxetine[17]

.

Dysphagia is estimated to be a complication in around 8.4% of cervical spinal procedures[18]

, resulting from disruption of the nerves involved in swallowing caused by localised surgical site swelling and manipulation of neck structures during the procedure. Patients may require the insertion of a nasogastric tube for safe administration of nutrition and medication. In such cases, the pharmacy team should advise on appropriate drug formulations for safe and appropriate administration. The issues of oral medication administration to patients with swallowing difficulties have been reviewed[19]

; however additional reference sources that can be consulted include:

- The relevant summary of product characteristics for the drug product;

- White R, Bradnam V (editors). Medicines Administration via Enteral Feeding Tubes. Pharmaceutical Press (www.medicinescomplete.com);

- Smyth J. NEWT guidelines for administration of medication to patients with enteral feeding tubes or swallowing difficulties (www.newtguidelines.com);

- Local medicines information service.

Ben Dorward is lead neurosciences pharmacist and Aaron Vere is rotational neurosciences pharmacist at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Department of Pharmacy, Royal Hallamshire Hospital. Lynda Gunn is nurse practitioner in neurosurgery at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Department of Neurosurgery, Royal Hallamshire Hospital.

References

[1] Tarulli A & Raynor E. Lumbosacral radiculopathy. Neurol Clin 2007;25(2):387–405. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2007.01.008

[2] The National Spinal Taskforce. Commissioning spinal services – getting back on track: a guide for commissioners of spinal services.

[3] Galbraith J, Butler J, Dolan AM et al. Operative outcomes for cervical myelopathy and radiculopathy. Advances in Orthopedics 2012; Article ID 919153. doi:10.1155/2012/919153

[4] Varanasi V. Lumbar Disc Herniation. Orthopedic Muscul Syst 2012;1:1. doi:10.4172/2161-0533.1000e101

[5] Dodward SNM, Dodward SJM & Savage J. Lumbar discectomy Review. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics 2015;25(3):177–186. doi:10.1053/j.oto.2015.06.001

[6] Komotar R, Mocco J & Kaiser M. Cervical management of cervical myelopathy: indications and techniques for laminectomy and fusion. The Spine Journal 2006;6:252S–267S. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2006.04.029

[7] Ferriter P, Mandel S, DeGregoris G et al. Cervical Myelopathy. Practical Neurology (BMC) 2014;April:43–46. Available at: http://practicalneurology.com/2014/04/cervical-myelopathy/ (accessed November 2015).

[8] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Guideline 173. Neuropathic pain – pharmacological management: The pharmacological management of neuropathic pain in adults in non-specialist settings. (2013). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg173 (accessed November 2015).

[9] Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Clinical Guideline 136. Management of Chronic Pain. (2013). Available at: http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/SIGN136.pdf (accessed November 2015).

[10] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS): Back pain – low, without radiculopathy (April 2015) Available at: http://cks.nice.org.uk/back-pain-low-without-radiculopathy#!topicsummary (accessed November 2015).

[11] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Guideline 88. Low back pain in adults: early management. (2009). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg88 (accessed November 2015).

[12] British Association of Spinal Surgeons. Lumbar Discectomy and Decompression: Advice for Patients Undergoing Surgery. Available at: http://www.spinesurgeons.ac.uk/patients/patient-information/lumbar-discectomy-and-decompression (accessed November 2015).

[13] Lavy C, James A, Wilson-McDonald J et al. Cauda equina syndrome. BMJ 2009;338:b936. doi:10.1136/bmj.b936

[14] Cheng J, Arnold P, Anderson P et al. Anticoagulation risk in spine surgery. Spine 2010;35(9):S117–S124. doi:10.1097/brs.0b013e3181d833d4

[15] Wilson L & Knaggs R. How to prevent and manage postoperative nausea and vomiting. Clinical Pharmacist 2012;4:85. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/learning/learning-article/how-to-prevent-and-manage-postoperative-nausea-and-vomiting/11096163.article (accessed November 2015).

[16] Verma R, Alladi R, Jackson I et al. Day case and short stay surgery: 2. Anaesthesia 2011;66:417–434. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06651.x

[17] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS): Neuropathic pain – drug treatment (June 2015) Available at: http://cks.nice.org.uk/neuropathic-pain-drug-treatment#!topicsummary (accessed October 2015).

[18] Ng CY & Gibson J. An aid to the explanation of surgical risks and complications: the international spinal surgery information leaflet. Spine 2011;36(26)2333–2345. doi:10.1097/brs.0b013e3182091bbc

[19] Wright D & Tomlin S. How to help if a patient can’t swallow. Pharmaceutical Journal 2011;286:271–274. Available at: http://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/learning/learning-article/how-to-help-if-a-patient-cant-swallow/11070063.article (accessed November 2015).

Further references:

The Melbourne Neurosurgery service provide accessible information on neurosurgical and spinal surgical procedures: http://www.neurosurgery.com.au/anatomy.html

The British Association of Spinal Surgeons provide useful information about spinal surgery and links to relevant guidance: http://www.spinesurgeons.ac.uk