This content was published in 2009. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Schizophrenia is a distressing psychiatric disorder with symptoms and long-term prognosis varying considerably between individuals. It encompasses a broad range of symptoms, including altered perception, thoughts, mood and behaviour. Although there continues to be public prejudice against people with schizophrenia many symptoms are commonly seen in the general population. For example, the lifetime prevalence of hallucinations is between 10 and 15 per cent and delusions of having special powers occur in 4 to 8 per cent, even in the absence of a psychiatric disorder.1 The label “schizophrenic” adds to prejudice and should no longer be used. In truth, there are good long-term outcomes for half of sufferers. Many patients, when well, are no different from people without the illness and even those with resistant and recurrent symptoms, if given appropriate treatment and support, can lead productive lives and be integrated into society.

Source: Louise Williams/Science Photo Library

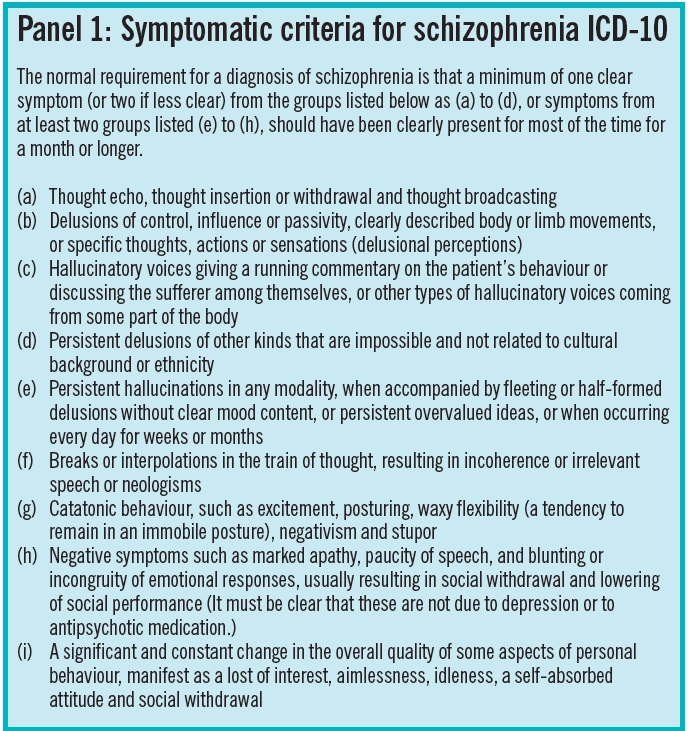

Schizophrenia is typically divided into acute and chronic phases. The acute phase is characterised by “positive” symptoms, such as hallucinations, paranoia, delusions and behavioural problems. It is these symptoms that often lead to admission to a psychiatric unit. The chronic phase can include reduced concentration, social withdrawal, apathy and bizarre ideas. This phase is harder to treat and can last for years. Intermittent attacks of acute illness can occur, usually depending on how successful treatment with an antipsychotic has been. A common symptom of schizophrenia is having a lack of insight to any illness. This can be a particular challenge for health professionals trying to persuade patients to take long-term antipsychotics. The formal symptomatic criteria for diagnosing schizophrenia is provided by the World Health Organization in the International Classification of Diseases currently in its 10th edition (see Panel 1).

The lifetime risk of schizophrenia is between 0.4 and 1.4 per cent.2 The condition is encountered in all cultures across the world, with men and women equally affected. It is referred to as “youth’s greatest disabler” by the WHO because it normally occurs between the ages of 15 to 35 years.2 The mortality risk in those with schizophrenia is 50 per cent higher than the general population, partly as a result of a high risk of suicide — about 10 per cent will commit suicide — and the high burden of physical health problems associated with the illness and antipsychotic medication.

There is no exact cause of schizophrenia and most research suggests a complex mixture of factors is involved. These include genetic predisposition, environmental factors, such as living in an urban environment, altered brain structure, substance misuse and biochemical theories, such as the dopamine hypothesis. The dopamine hypothesis suggests that schizophrenia is caused by dopamine overactivity in the pre-frontal cortex. To support this is the observation hat all antipsychotics block or partially block (as with aripiprazole) dopamine receptors, specifically D2 receptors, which are the most abundant dopamine receptors in the brain. Other neurotransmitters are also likely to be involved but are less understood. These include serotonin, glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid.

Identify knowledge gaps

- What are symptoms of schizophrenia?

- What are the common side effects of antipsychotic medicines?

- Why is it particularly important for people with schizophrenia to have general health checks?

Before reading on, think about how this article may help you to do your job better. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s areas of competence for pharmacists are listed in “Plan and record”, (available at: www.uptodate.org.uk). This article relates to “disease states and their drug therapy” (see appendix 4 of “Plan and record”).

Non-drug treatments

Treatment with antipsychotics continues to be the principle intervention for people with schizophrenia. However, a number of psychological approaches have been gaining favour and evidence over the past few years. They are usually tried in combination with antipsychotics or in those who are not adequately treated by antipsychotics alone. In the recently updated National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines on schizophrenia,3 arts therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and family interventions were recommended. Arts therapy promotes self-expression and is particularly recommended for those with prominent negative symptoms. CBT enables patients to explore their thoughts and feelings towards symptoms and promotes alternative ways of coping with them. CBT should be available to all those with schizophrenia because it is believed to reduce readmission and length of bed stay. Family therapy tries to engage those closest to the service user and provides education and support with problem solving approaches. Access to psychological therapies has recently been improved by a Government initiative but engaging patients long enough for successful treatment can be problematic.

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics are broadly divided into typical (first generation) and atypical (second generation). This classification is loosely based on the fact that the atypical antipsychotics are, supposedly, less likely to cause extrapyramidal side effects (EPSE) that are also referred to as movement disorders. However, this can be confusing because the antipsychotics vary considerably and are not homogenous. Many so called atypical drugs, for example, have typical-like side effects even within the normal therapeutic range. It is, therefore, probably more accurate to consider the antipsychotics as one group but with distinct differences between individual drugs.

To add to the debate, there have been a number of recent meta-analyses and naturalistic studies questioning the efficacy differences between the typical and atypical antipsychotics. In the two largest and most recent meta-analyses only four atypical antipsychotics — clozapine, olanzapine, amisulpride and risperidone — appeared slightly more effective than others.4,5 Clozapine is rather unique in terms of efficacy and has been conclusively shown to be more effective in treatment resistant schizophrenia than other antipsychotics. In some patients with a severeand enduring illness it probably represents the besthope for recovery. The NICE guidelines on schizophrenia reflect these recent studies and now recommend that any antipsychotic could be used fortreating the condition after considering the individual drug side effects and the views of the service userand carer if appropriate.

Adverse effects

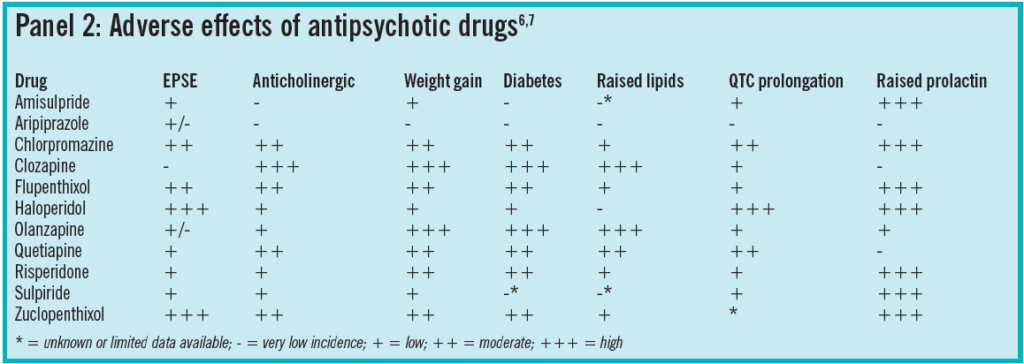

Potential adverse effects of the antipsychotics vary considerably across the class (see Panel 2). This is in part, due to which neurotransmitters the antipsychotic affects.

EPSE

Dopamine blocking adverse effects include EPSEs and hyperprolactinaemia. These adverse effects depend on the affinity of the antipsychotic for striatal D2 receptors. They are routinely seen with typical antipsychotics and less frequently with the atypical antipsychotics. This is not without exception and risperidone, paliperidone and amisulpride, (atypical antipsychotics), often cause hyperprolactinaemia and movement disorders, particularly at the higher doses.

EPSEs include pseudoparkinsonism, dystonia, akathesia and tardive dystonias. In pseudoparkinsonism effects similar symptoms to Parkinson’s disease, such as bradykinesia, tremor and rigidity, are seen. Dystonias are a sustained or repeated involuntary muscular contraction, which, if it includes the laryngeal muscles, is an emergency requiring immediate intramuscular or intravenous procyclidine orbenzatropine. Akathesia presents as a compulsion to keep moving. Tardive dyskinesias are late appearing, often irreversible, involuntary movements. Symptoms vary in severity and muscles affected but may include a constant protruding tongue, lip smacking or neck twisting.

Treating EPSEs includes either reducing or stopping the offending antipsychotic or switching to anatypical antipsychotic. If the drug cannot be switched, as is often the case with depot antipsychotics, prescribing an anticholinergic such as procyclidine or or phrenadrine can be useful in pseudo parkinsonism and dystonias. Anticholinergics are not considered useful in akathesia and should be avoided in tardive dyskinesia because symptoms can worsen.

Hyperprolactinaemia

Hyperprolactinaemia iscaused by dopamine blockade in the tubero-infundibular pathway in the brain. Most antipsychotics cause a prolonged increase in prolactin withthe exception of aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapineand quetiapine. Many patients appear asymptomatic even with a high prolactin level while others experience sexual dysfunction, menstrual changes, milk production (galactorrhoea) and breast enlargement (gynaecomastia). Persistently high prolactin over many years has been associated with a reduced bone mineral density and a higher rate of breast cancer. With the exception of menstrual changes these adverse effects can be seen in both men and women.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare (incidence of 0.01–0.02 per cent)8 but potentially fatal adverse reaction related to dopamine blockade. It is thought to be caused by the sudden blockade of dopamine in thetemperature regulatory centres found in the hypothalamus and corpus striatum. It is characterised by fever, severe muscle rigidity and mental state changes. Immediate medical attention and cessation of the offending antipsychotic are essential in suspected NMS because death results in 10 per cent of cases. Those who are newly prescribed a potent dopamine blocking antipsychotic are dehydrated or present with physical exhaustion are more likely to develop NMS.8

Weight gain and vascular risks

Antipsychotics canalso worsen or cause weight gain, diabetes and dyslipidiaemias, which can increase a patient’s cardiovascular risk. Clozapine and olanzapine are associated with the greatest metabolic changes but most other antipsychotics have also been implicated. Weight gain may be in part be mediated through the blockade of histamine (H1) receptors, which enhances appetite via the hypothalamic eating centres.9 The average weight gain with olanzapine is 3.5 to 4kg within the first 10 weeks of treatment.9 This can affect patients’ self esteem as well as increase their risk of type 2 diabetes. An increased risk of diabetes with antipsychotics, however, can also be seen in the absence of weight gain.Why this occurs in under investigation but may be related to high triglyceride levels and antagonism of muscarinic M3 receptors, both of which alter insulin homeostasis.9 Triglyceride levels can appearraised while high-density lipoproteins are lowered.9 Again the antipsychotics differ in their ability tocause dyslipidaemia but haloperidol and aripiprazole appear to have no effect on lipids.

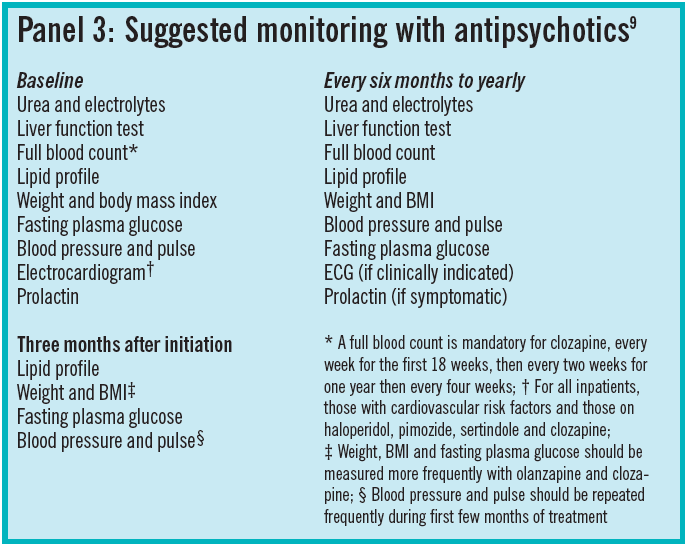

Why people with schizophrenia have a higher incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular complications than the general population is likely to be multifactorial and includes increased incidence of smoking, isolation, poor personal care and a direct genetic link between diabetes and schizophrenia. These complications mean that people with schizophrenia have a 10- to 30-year reduced life span compared with the general population9 and this highlights the importance of health monitoring for this vulnerable patient group (see Panel 3).

Other

Other adverse effects associated with antipsychotics include sedation, anticholinergic effects (eg, constipation, urinary retention and confusion), a reduced seizure threshold, hypotension and QT prolongation. The QT interval represents the timetaken to complete the depolarisation and repolarisation cycle of the ventricles. QT prolongation is suggested as a risk factor for torsade de points and sudden cardiac death, although other factors may also be involved. The risk of QT prolongation and other cardiovascular complications have prompted NICE in their latest guidance to recommend an electrocardiogram for all those starting on an antipsychotic as an inpatient or in those with any underlying cardiovascular risk.3

Despite these adverse effects antipsychotics remain the principle intervention for treatment and long-term prevention of schizophrenia.

Depot preparations

Antipsychotics are availableas liquids, oral dispersible tablets and both short-and long-acting intramuscular injections. Depot preparations of typical antipsychotics produce a predictable release of drug over two to five weeks.

Risperidone is the only atypical long acting injection (LAI) currently available. The drug is encapsulated in a polymer to form microspheres and the formulation takes three to four weeks to breakdown, meaning there is a three-week lag after administration, before risperidone is released. Therefore, patients on risperidone LAI require additional antipsychotic cover for the first three or four weeks of treatment which is usually tapered down and stopped over the following two weeks. Olanzapine LAI has recently been granted a European medicine licence but will not be launched in the UK until mid 2010. There are reports of an unpredictable post-injection syndrome (where similar symptoms to olanzapine overdose are seen) so it will be restricted to use in health care facilities only and require patients to remain in the facility for three hours after the injection for observation.

LAIs can help improve compliance and reduce relapse rates but if adverse effects develop they are likely to be prolonged. For this reason a small test dose of injection is required. With risperidone LAI and olanzapine LAI, a test dose is not practicable so it is recommended that patients try oral preparations first.

Clozapine

Clozapine was the first atypical antipsychotic to be developed and is recommended for those whose illness has not responded adequately to treatment despite the sequential use of at least two different (including one atypical) antipsychotics, both of which have been given for an adequate time and dose.3 It is unclear why clozapine is more effective in treatment-resistant schizophrenia but it has a diverse and unique pharmacology affecting multiple receptors. This may also explain its wide range of adverse effects, which can be severe and life-threatening. These include agranulocytosis, constipation, tachycardia, hypersalivation and the metabolic changes already discussed. Mandatory differential white cell counts are required with clozapine and it can only be dispensed following a satisfactory result. The patient, prescriber and pharmacy also have to be registered with the clozapinecompany monitoring white cell counts. Because of the potential adverse effects, physical health monitoring is especially important in those prescribed clozapine and the drug is usually dispensed and monitored by hospital pharmacies.

The evidence base for those who do not respond or cannot tolerate clozapine is poor and expert advice must be sought. Occasionally clozapine is augmented with another antipsychotic such as amisulpride or aripiprazole.10 Where clozapine cannot be used (eg, in those refusing blood tests) higher than usual doses of some antipsychotics are occasionally tried.7

Combining antipsychotics or using higher thanusual doses carries a significant health risk, with additive adverse effects.

Summary

People with schizophrenia experience distressing symptoms which may alienate them from family, friends and society. Antipsychotics remain the mainstay of treatment but are associated with a multitude of adverse effects, which, accompanied by the illness itself, can increase cardiovascular risk and reduce life expectancy. Regular and timely health monitoring is essential for all those suffering schizophrenia.

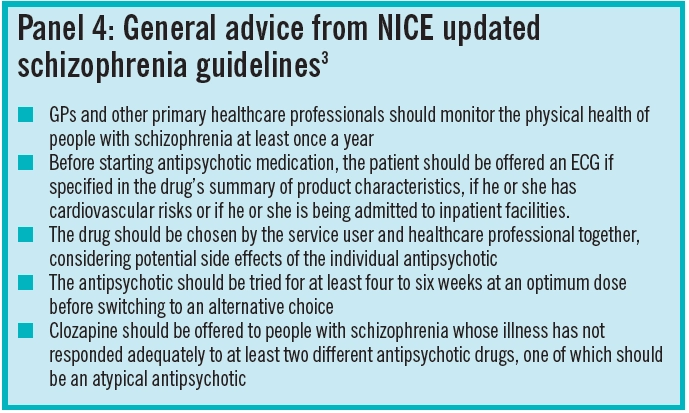

General advice from the updated NICE guidelines appears in Panel 4.

Further reading

- Taylor D. Schizophrenia in focus. Pharmaceutical Press; London: 2006.

Signposting

- Time to Change is a national campaign aiming to end the stigma associated with mental illness. www.time-to-change.org.uk.

- The Choice and Medication website offers peer reviewed, patient friendly advice on all medicines used in mental illness (www.choiceandmedication.org).

- Rethink is a leading National charity for anyone affected by a serious mental illness( www.rethink.org; tel 0207840 3188).

Action: practice points

Reading is only one way to undertake CPD and the Society will expect to see various approaches in a pharmacist’s CPD portfolio.

- Help reduce the stigma associated with mental illness by downloading materials and a toolkit from the time to change website. Find out if there is a local event happening near you.

- Check if your clients on antipsychotics have had an annual physical healthy check?

- Discuss adherence and potential adverse effects with a client on a long term antipsychotic.

Evaluate

For your work to be presented as CPD, you need to evaluate your reading and any other activities. Answer the following questions: What have you learnt? How has it added value to your practice? (Have you applied this learning or had any feedback?) What will you do now and how will this be achieved?

References

- Johns L, Os JV. The continuity of psychotic experiences in the general population. Clinical Psychology Review 2001;21:1125–41.

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Schizophrenia update. 2009. Available at www.nice.org.uk (accessed on 19 June 2009).

- Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM. Second-generation versus first generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:31–41.

- Leucht S, Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C,Hunger H, Schmid F et al. A meta-analysis of head to head comparisons of second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 2009;166:152–63.

- Bazire S. Psychotropic drug directory 2009. Aberdeen: Healthommunications UK;2009.

- Taylor D, Paton C, Kerwin R. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines. 9th Edition. London: Informa Healthcare;2007.

- Strawn J, Keck P, Coroff S. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry 2007;164:870–6.

- Stahl SM, Mignon L, Meyer JM. Which comes first: atypical antipsychotic treatment or cardiometabolic risk? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2009:119;171–9.

- Taylor D, Smith L. Augmentation of clozapine with a second antipsychotic – a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2009:119;419–25.

CPD articles are commissioned by The Journal and are not peer reviewed.

You might also be interested in…

Specialist mental health pharmacist clinics in primary care: a service evaluation supporting integrated neighbourhood working

Stopping antidepressants in pregnancy linked to higher risk of mental health emergencies