Science Photo Library

Readers should be aware that, as of 31 January 2024, new regulatory measures state that valproate must not be started in new patients aged under 55 years, unless two specialists independently agree there is no other effective or tolerated treatment, or there are “compelling reasons” that the reproductive risks do not apply. More information can be found here: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/news/new-valproate-prescriptions-must-be-signed-off-by-two-specialist-doctors-from-january-2024-says-mhra

Valproate (sodium valproate and valproic acid) is licensed in the UK (see Box 1) for the treatment of epilepsy and bipolar disorder, and is a black triangle medicine, subject to additional safety monitoring[1],[2]

. Although this article will not focus on off-label indications, it is important to note that this advice is applicable to the prescribing and dispensing of valproate irrespective of the indication.

Box 1: Brands of valproate available in the UK (December 2020)

- Belvo (Consilient Health)

- Convulex (Gerot Lannach UK Limited)

- Depakin (imported [Italy])

- Depakote (Sanofi)

- Dyzantil (Aspire Pharma Ltd)

- Epilim (Sanofi)

- Episenta (Desitin Pharma Ltd)

- Epival (Healthcare Pharma Ltd)

- Orlept (Wockhardt UK Ltd)

- Syonell (Lupin Healthcare [UK] Ltd)

Other named generic versions may also be available.[1]

Valproate is a broad spectrum anticonvulsant agent that is used in adults for the management of bipolar disorder and many different seizure types and syndromes. It is used as follows:

- First-line and as adjuvant treatment for tonic-clonic, absence and myoclonic generalised seizures;

- First-line for atonic and tonic generalised seizures;

- Second-line and as adjuvant treatment for focal seizures (with or without secondary generalisation);

- At various points in treatment pathways for epilepsy syndromes (e.g. Lennox-Gastaut and Dravet)[3]

.

Despite its efficacy, the mode of action of valproate is still not fully understood. Its anticonvulsant action is thought to be via potentiation of the inhibitory action of gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) through an action on the further synthesis or metabolism of GABA[4]

.

This article discusses the issues associated with valproate use in women and children of childbearing age, and outlines how pharmacy can minimise the risks in practice through completion of safety checks and enrolment onto a pregnancy prevention programme (PPP). It also explores how to manage ethical challenges and the changes to current practice, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Historic use in women

Since its initial introduction in the early 1970s, valproate use has been cautioned in women of childbearing potential[5]

. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency’s (MHRA’s) definition of a woman of childbearing potential is “a pre-menopausal female (from menarche to menopause) who is capable of becoming pregnant”[6]

. The first data sheet on valproate, published in 1975 in the Association of British Pharmacy Industry (ABPI) Data Sheet Compendium, indicated that valproate “has been shown to be teratogenic in animals. Any benefit that may be expected from its use should be weighed against the hazard suggested by these findings”[7]

.

Over time, as the risks of congenital malformations and developmental disorders to unborn children (see ‘Valproate use and pregnancy’) have become increasingly understood, related warnings have, consequently, been strengthened[5]

.

In November 2014, the Coordination Group for Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures (CMDh) — a regulatory body representing European Union member states — agreed to strengthen the warning on the use of valproate in women or girls of childbearing potential. They advised that valproate should not be used during pregnancy, or in women or girls of childbearing potential, unless clearly necessary[8]

.

In January 2015, the MHRA consolidated this new regulatory guidance in the UK[9]

. Prescribers had an obligation to ensure that all female patients were informed about valproate and understood the risks associated with taking the medicine during pregnancy, as well as the need for effective contraception and to review if planning a pregnancy. The MHRA produced a toolkit to support these discussions, including a patient guide to be issued to all women or girls of childbearing potential started on valproate by prescribers, and a patient card to be issued by pharmacists whenever valproate is dispensed for women or girls of childbearing potential[10]

.

Despite these steps, around 3.3 per 10,000 pregnancies in the UK in 2017 were exposed to valproate — equating to around 250 live births[11]

. A survey of 2,000 women with epilepsy, aged 16-50 years — conducted the same year by the charities Epilepsy Action, Epilepsy Society and Young Epilepsy — indicated that 18% of women taking valproate were unaware of the risks that the medicine can pose in pregnancy, 28% of women taking valproate had not been informed of the risks of the medicine in pregnancy and 68% of women taking valproate had not received any materials from the MHRA toolkit[12]

.

This survey formed part of a wider review, conducted by the European Medicines Agency, and the collection of evidence (through written submissions, expert meetings and a public hearing), as well as consultation with healthcare professionals and patients, including women and children affected by valproate use during pregnancy. It concluded that women were still not receiving the right information in a timely manner, despite previous recommendations. Consequently, in 2018, the CMDh recommended new advice on the use of valproate in women or girls of childbearing potential[13],[14]

.

The MHRA introduced new regulatory guidance in March 2018 in the UK, stating that valproate should no longer be prescribed for women or girls of childbearing potential unless they are on a PPP — on the condition that all other treatments are ineffective or not tolerated as judged by an experienced specialist in epilepsy or bipolar disorder[15]

. Valproate is now contraindicated in pregnancy for the treatment of bipolar disorder and should only be used in epilepsy if no alternative is available[15]

.

Since the MHRA introduced this new advice, further patient surveys have shown that ongoing effort is required to ensure this guidance is followed[16]

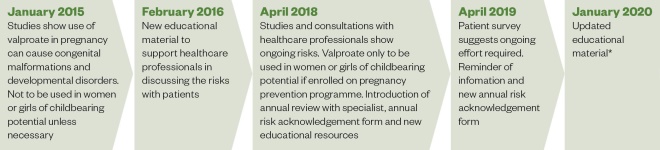

. Figure 1 provides a timeline of MHRA warnings and guidance on the use of valproate in pregnancy and women or girls of childbearing potential[9],[10],[15],

[16]

.

Figure 1: Timeline of Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency warnings and guidance on the use of valproate in pregnancy and in women or girls of childbearing potential

Source: Source: Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency[9],[10],[15],

[16]

*Distribution of updated risk minimisation materials will be complete by December 2020

Valproate use and pregnancy

Valproate is known to cause serious issues if used in pregnancy. These include:

- Congenital malformations — if valproate is taken in pregnancy, around 1 in 10 babies (10.73%) are at risk of developing congenital malformations, compared with a 2-3% risk in the general population. The most common types of congenital malformations include neural tube defects; facial dysmorphism; cleft lip and palate; craniostenosis; cardiac, renal and urogenital defects; limb defects; and multiple anomalies involving various body systems[6]

. Folic acid supplementation may decrease the general risk of neural tube defects, but there is evidence that this does not reduce the risks associated with in utero valproate exposure[6]

. - Developmental disorders — if valproate is taken in pregnancy, up to 4 in 10 babies (40%) are at risk of development disorders[5]

. These include delays in early development, such as talking and walking later, lower intellectual abilities, poor language skills (speaking and understanding), memory problems, and increased risk of autism/autistic spectrum disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. However, there is limited data available on the long-term outcomes for these children[6]

.

Reducing the risk of valproate use in pregnancy

Owing to the serious risk of congenital malformations and developmental disorders with valproate use in pregnancy, the 2018 MHRA regulatory guidance provides details of changes to practice for healthcare professionals, including pharmacists[15]

.

Pregnancy prevention programme

All women or girls of childbearing potential prescribed valproate must be enrolled on a PPP – also known as ‘PREVENT’. This includes women or girls of childbearing potential who are not sexually active, unless there are clear reasons to indicate that there is no risk of pregnancy (e.g. patient has had a hysterectomy)[15]

.

The PPP ensures that:

- Patients are informed and understand the risks of valproate use in pregnancy — confirmed by signing an annual risk acknowledgment form (ARAF);

- Patients take/use highly effective contraception or two complementary forms of effective contraception, including a barrier method if necessary (see ‘Contraception’);

- Patients have treatment reviewed with their specialist at least once per year[15]

.

The MHRA has produced several resources for healthcare professionals to use to implement the PPP (see Figure 2).

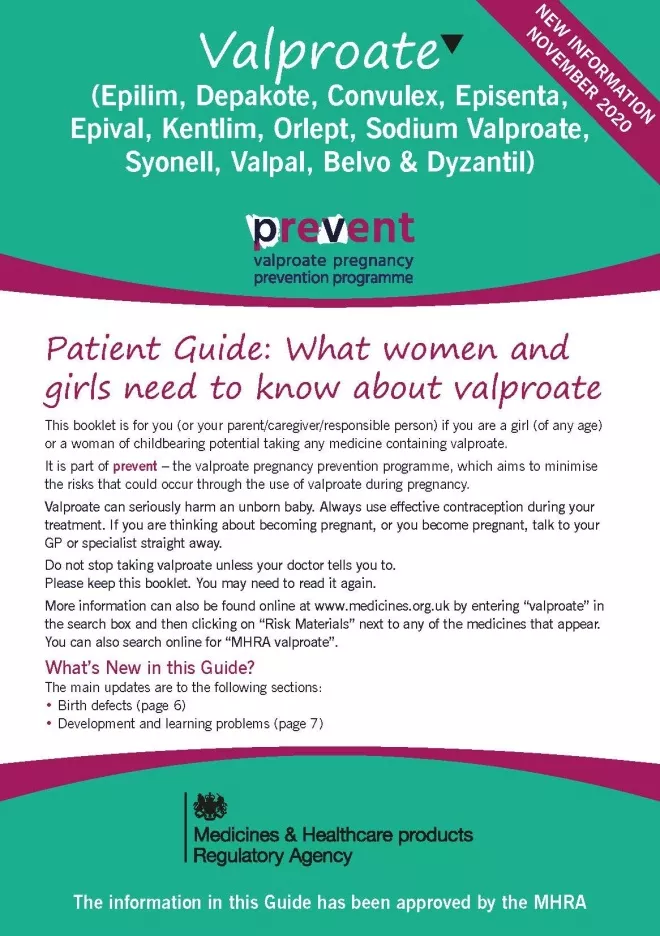

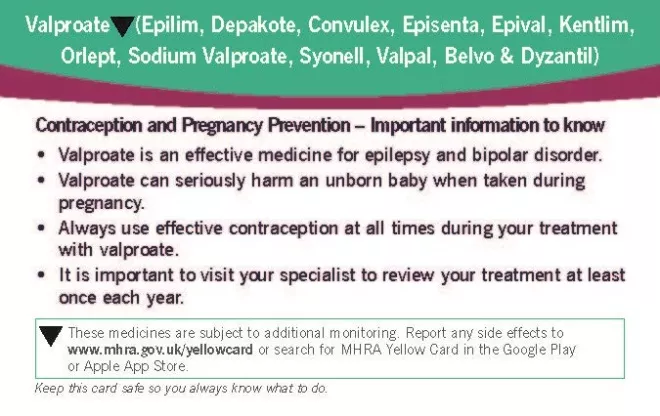

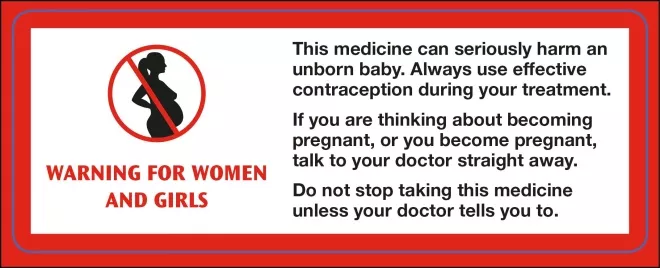

Figure 2a: Valproate warning materials*

Source: Guide for Healthcare Professionals

Figure 2b: Valproate warning materials*

Guide for Healthcare Professionals

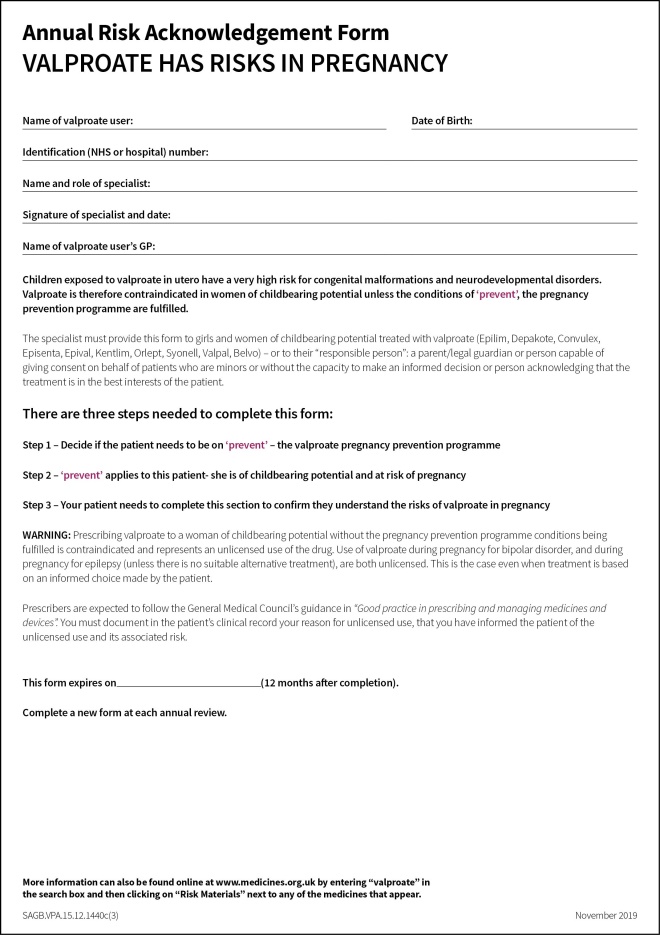

Figure 2c: Valproate warning materials*

Annual risk acknowledgement form to be signed by patient and specialist

Figure 2d: Valproate use in women

Patient card to be provided every time valproate is dispensed by pharmacy

Figure 2e: Valproate warning materials*

Warning sticker for attachment to the outer box when valproate is dispensed outside of the original packaging

A patient guide (Image 2A) must be provided to any woman or girl of childbearing potential (or carer/responsible person, where appropriate) who is starting or continuing treatment with valproate. The patient guide should be provided by the specialist initiating treatment, but pharmacists should check it has been provided upon dispensing and supply it to the patient if required.

The

Guide for Healthcare Professionals

(see Image 2B) contains guidance for all prescribers, pharmacists and other healthcare providers involved in the care of women or girls of childbearing potential prescribed valproate.

The ARAF (see Image 2C) is signed by the specialist and patient (or carer/responsible person, where appropriate) at initiation and at annual review. A copy should be given to the patient, filed in the specialist notes and sent to the patient’s GP. Pharmacists should remind the patient or carer of the importance of annual specialist review. If this review is overdue, pharmacists should make the supply but refer the patient to their GP — contacting the GP if necessary.

Pharmacists should give a patient card

(see Image 2D) to women or girls of childbearing potential every time valproate is dispensed and add the valproate warning sticker (see Image 2E) to the outer packaging whenever valproate is dispensed outside of the original packs. Original packs already contain this warning and should be dispensed whenever possible[15]

.

In addition, valproate is contraindicated in pregnancy for the treatment of epilepsy unless there is no suitable alternative treatment. For patients treated for bipolar disorder, valproate is contraindicated in pregnancy[15]

.

Contraception

As per the PPP, women or girls of childbearing potential prescribed valproate must also be prescribed either one highly effective method of contraception or two complementary effective methods of contraception, including a barrier method[6]

.

Contraceptive methods are designated either highly effective or effective based on their failure rates in typical use in the first year. Typical use includes user error or use in circumstances that decrease efficacy, such as interactions with concomitant medicines[17]

.

Highly effective contraception methods have a typical failure rate of 1% and include male and female sterilisation (see Table 1)[17],[18]

. Methods designated as highly effective include:

- Copper intrauterine devices (IUD) — highly effective from three weeks post implantation for five to ten years (depending on the IUD used);

- Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (IUS) — highly effective from three weeks post implantation for three to five years (depending on the IUS used);

- Progesterone implant — highly effective from three weeks post implantation if there is no concurrent use of interacting medicines, which may affect efficacy;

- Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate subcutaneous or intramuscular injections — only considered highly effective three weeks after first administration and with repeated injections documented and administered on schedule by a healthcare professional[17]

.

Effective contraception methods have higher failure rates compared with highly effective contraception in the first year with typical use[17]

. These must be combined with a barrier method and frequent pregnancy testing to satisfy the conditions of the PPP[6]

. Methods designated as effective contraception include:

- Combined hormonal contraceptives (such as pills, patches or a vaginal ring) that are effective once used consistently for more than three weeks;

- Progestogen-only pill – which is effective once used consistently for more than three weeks[17]

.

| Method | Typical use (%) | Perfect use (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No method | 85 | 85 |

| Fertility awarness-based | 24 | 0.4-5 |

| Female diaphragm | 12 | 6 |

| Male condom | 18 | 2 |

| Combined hormonal contraceptives (e.g. pills, patches or vaginal ring) | 9 | 0.3 |

| Progestogen-only pill | 9 | 0.3 |

| Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate subcutaneous or intramuscular injections | 6 | 0.2 |

| Copper intrauterine device | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Progesterone implant | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Female sterilisation | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Male sterilisation | 0.15 | 0.1 |

| Source: Reproduced with permission from the Royal College of General Practitioners, Association of British Neurologists and Royal College of Physicians[18] | ||

Pregnancy test

To ensure the patient is not pregnant there is a need to take a pregnancy test prior to prescribing a valproate-based medicine. However, a pregnancy test may not detect an early pregnancy that could have occurred after unprotected sex in the preceding three weeks. Women or girls of childbearing potential should have a repeat pregnancy test three weeks after starting a new contraceptive method if there was any risk of pregnancy prior to starting contraception, even if the first test was negative[17]

.

Patient enrolment in the pregnancy prevention programme

All women or girls of childbearing potential who are taking valproate, regardless of indication, should be enrolled on the PPP. The only exception is when the specialist considers there are compelling reasons to indicate that there is no risk of pregnancy:

- Permanent absence of risk of pregnancy (e.g. post-menopausal women or those who have had a hysterectomy) — enrolment on the PPP will not be required;

- Changing risk of pregnancy (e.g. patient is pre-menarchal) — enrolment on the PPP will be required in the future and risks should be discussed yearly or sooner if the situation changes;

- Sexual activity that could lead to pregnancy will not occur before the next annual review — the PPP will be reconsidered at next annual review[6]

.

Shared care

A specialist prescriber who initiates treatment is defined in the Guide for Healthcare Professionals as a consultant neurologist, psychiatrist or paediatrician who regularly manages complex epilepsy or bipolar disorder[6]

. The specialist prescriber may delegate PPP activities to other healthcare professionals working as part of their multidisciplinary team (e.g. epilepsy specialist nurses [ESNs] or pharmacist independent prescribers). Other healthcare professionals working under a specialist prescriber are considered competent to perform these roles, provided prescribing decisions and switching medicines is performed under the consultant’s guidance[6]

.

ESNs have been proven to increase patient satisfaction with support and information provided to people with epilepsy[19]

. ESNs often have strong pre-existing relationships with patients and their carers, making them ideal candidates to lead PPP consultations. Pharmacists running an epilepsy clinic under a specialist prescriber are similarly well placed to implement the PPP.

Most specialist services will request for valproate to be prescribed in primary care by the patient’s GP[18]

. However, even when a GP agrees to prescribe valproate, the specialist prescriber retains accountability for PPP implementation, including discussing the risks of treatment, provision of the patient guide, completion of the ARAF, arranging for highly effective contraception and excluding pregnancy before the first prescription is issued[18]

. The specialist prescriber must also agree to see the patient urgently (within days) if referred owing to unplanned pregnancy or if she wants to plan a pregnancy[6]

. Effective communication between the specialist prescriber and the GP is essential to ensure the safe prescribing of valproate in primary care.

In accordance with the General Medical Council, the person who signs the prescription undertakes ultimate responsibility for the safety of their prescribing[18]

. The GP must therefore be confident that the specialist prescriber has performed their duties and that any woman or girl of childbearing potential prescribed valproate has an up-to-date signed ARAF each time a repeat prescription is requested, referring back to the specialist service when the annual review is required.

How pharmacy can minimise the risk

The role pharmacists and members of the pharmacy team have in minimising the risk associated with valproate exposure during pregnancy is explicitly detailed in the Guide for Healthcare Professionals

[6]

. It is necessary that the entire pharmacy team understands what they must do to ensure the important safety checks are performed, as outlined in Box 2.

Box 2. Safety checks that members of the pharmacy team must perform when dispensing valproate to a woman or girl of childbearing potential

Counter Assistants

- Discreetly inform the pharmacist whenever a valproate prescription is handed in for a woman or girl of childbearing potential, even if it is being collected by someone else on their behalf.

Dispensers

- Dispense valproate in original packages whenever possible; there must be a valid reason for providing valproate outside of original packages (e.g. weekly dispensing as the patient is at risk of medication overuse). Whenever dispensing valproate outside of original packs, the valproate warning sticker must be added to the outer box (see Figure 2);

- Provide a patient card every time valproate is dispensed to a woman or girl of childbearing potential (see Figure 2).

Pharmacy technicians

- Ensure valproate is dispensed in original packs whenever possible and that a patient card is provided ;

- Discreetly pass to the pharmacist for discharge counselling upon accuracy check completion.

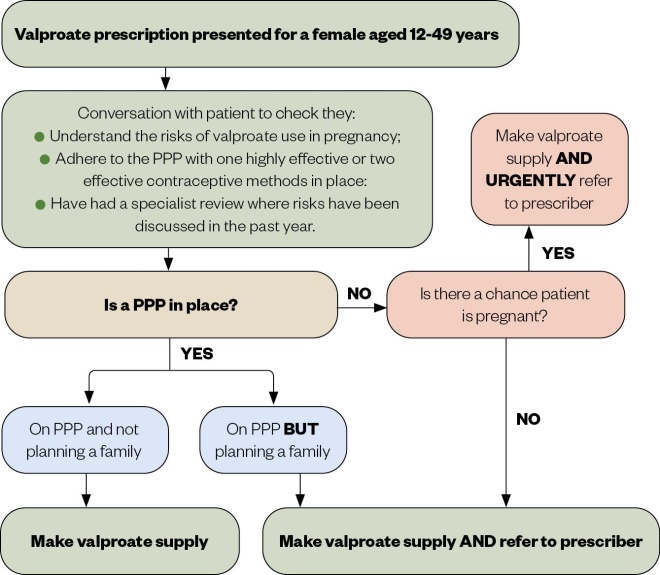

Pharmacists

- Remind women or girls of childbearing potential of the:

- Risks of valproate in pregnancy and ensure she has a patient guide (see Figure 3);

- Importance of the annual specialist review for treatment review and completion of the ARAF (see Figure 3);

- Need for highly effective contraception or two complementary forms of effective contraception, including a barrier method;

- Need to continue taking valproate but to see her GP or specialist immediately if wishing to plan a pregnancy or pregnancy is suspected[16]

- This is a sensitive conversation and as such needs to be approached carefully, with the use of the pharmacy consultation room if available. The valproate supply pathway (see Figure 3) outlines how pharmacists can approach these consultations.

The MHRA definition of a woman of childbearing potential does not include a definitive age range, which can cause debate as to who exactly pharmacists should target for risks of valproate in pregnancy discussions[6]

. The ‘

Safe Supply of Valproate Medication

’ developed by pharmacy organisations, including the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, states that pharmacists should counsel every woman aged between 12 and 49 years[20]

. However, 21.7% of British teenagers surveyed in southern England reported having reached menarche before their 12th birthday, with 0.8% having had their first period before age 10[21]

. It is possible to become pregnant prior to the menarche and incidences of natural conception have been reported beyond age 50. Consequently, pharmacists should consider discussion about risks of valproate in pregnancy for all females prescribed the drug.

Pharmacists have an important role in encouraging medication adherence, even when they identify cases where the conditions of PPP are not satisfied. The ‘Safe supply of valproate medication’ states that no woman or girl should stop taking valproate without first speaking to her doctor, and that pharmacists should always dispense the prescription (when otherwise clinically appropriate)[20]

. When conditions of the PPP are not satisfied, the pharmacist should also provide the patient with counselling on its importance and, as per the Guide for Healthcare Professionals, contact the GP directly if necessary[6]

.

Medication adherence and improving seizure control are essential in lowering the risk of sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP)[22]

. Every single convulsive seizure, including those precipitated by abrupt cessation of antiepileptic drugs (e.g. valproate), increases the likelihood of SUDEP. In addition to reduced seizure control, studies have linked non-adherence to antiepileptic drugs with lowered quality of life, decreased productivity, seizure-related job loss, and seizure-related motor vehicle accidents[23]

. Pharmacists must remind any woman or girl of childbearing potential with epilepsy who expresses a desire to abruptly stop taking valproate of these risks, encourage continued use and refer to the GP for onwards specialist review.

Poor seizure control owing to abrupt cessation of an antiepileptic drug in a pregnant patient can also cause harm to the foetus. In addition to the risk of trauma, seizures in pregnancy have been associated with lower birth weight for gestational age and detrimental effects on the child’s neurodevelopment[24]

.

Figure 3: Valproate supply pathway

PPP: Pregnancy prevention programme

Source: Adapted with permission from the Royal Pharmaceutical Society[20]

In October 2018, the General Pharmaceutical Council stated that inspections of registered pharmacies will include checking compliance with the responsibilities outlined in the MHRA PPP for valproate, with registered pharmacies forced to take immediate action to resolve any deficiencies in their practice identified during an inspection[25]

.

However, despite this and the availability of guidance outlining the relevant safety checks and PPP toolkits, several recent audits and surveys have shown that patients are still not receiving the appropriate counselling and information on the risks of valproate when the medicine is dispensed through pharmacy. A UK audit undertaken by the Company Chemists’ Association (CCA) between February and March 2019 found that only 40.1% community pharmacies (n=6,480) issued patient cards when dispensing valproate[26]

. This was an improvement from the 21.4% of pharmacies issuing a patient card during the first part of this audit — undertaken between July and October 2018 (n=6,761) — but there is clearly room for improvement[26]

. In addition, a survey of 514 women prescribed valproate between October 2019 and January 2020 demonstrated that the lack of provision of patient cards is not the only area that pharmacy must improve. Pharmacists had only discussed the risks of valproate with 49% of respondents, while 29% had been dispensed valproate outside of the original packaging without the addition of a warning sticker[27]

.

A valproate audit looking at adherence to the PPP was included as part of the NHS England community pharmacy contractual framework pharmacy quality scheme (PQS) in 2019/2020[28]

. Pharmacies wishing to assess their own practice could utilise the data collection tool developed for this audit, which is available from the PQS guidance (Annex 10) on the NHS England website. This tool can be used by pharmacists to promote wider engagement with the requirements among members of the pharmacy team.

Challenging scenarios

The guidance and responsibilities for each healthcare professional outlined by the MHRA PPP are explicitly clear. However, the patient population prescribed valproate can be complex and comorbidities can make compliance challenging. Ethical challenges can arise, including lack of capacity to make informed choices owing to intellectual disability; and informed consent with refusal to participate in the PPP on religious or cultural grounds.

When faced with ethical challenges, pharmacists should consider consulting multidisciplinary team members such as the GP, ESN and specialist prescriber. Additional resources may be appropriate in certain situations, such as best interest meetings; advice from trust or health board medicines committees, or clinical directors; and speciality support groups. Although there are many challenging scenarios that can arise, some of those that pharmacists are likely to encounter in routine practice are addressed below.

Transition from child to adult services

The transition from paediatric epilepsy care or child and adolescent mental health services to adult care is a time when behavioural and compliance issues may be particularly challenging, owing to lifestyle changes throughout adolescence[18]

. The PPP must be initiated at menarche, which may occur at the time that patients are transitioning between paediatric and adult care[6]

. However, anecdotal evidence has suggested that young women can sometimes ‘fall through the cracks’[18]

. Where community pharmacists identify incidences where the ARAF has expired, the prescription for valproate should still be dispensed, but the pharmacist must refer the young woman back to her GP (contacting the GP personally if required)[6]

Young women may confide in a pharmacist that they have become sexually active but are not currently on the PPP. In these instances, the prescription should still be issued but pharmacists should strongly encourage the young woman to speak to her GP for referral to the specialist and PPP implementation.

Intellectual disability

The prevalence of epilepsy in individuals with intellectual disability is high, comprising 25% of the total epilepsy population and 60% of the treatment-resistant epilepsy population[18]

.

There are women or girls of childbearing potential on valproate in whom intellectual disability with lack of mental capacity mean that discussion with the girl or woman herself cannot take place, and in whom consent to sexual activity would be impossible[18]

. This will include many girls and women with specific epilepsy syndromes, such as Lennox-Gastaut or Dravet syndrome, for which valproate is the recommended first-line treatment[3]

.

Pharmacists must be mindful that discussing valproate and pregnancy risk with the carer or family of a woman or girl of childbearing potential with significant intellectual disability and lack of mental capacity can be distressing for those involved and thus must be tactfully handled. As per the ‘Safe supply of valproate medication’, this involves discussing childbearing potential and intentions to start a family in a sensitive manner, making use of a private area of the pharmacy or consultation room[20]

. Although these conversations may be difficult, it is important that pharmacists use their professional judgement when deciding how to approach and discuss these issues.

Women or girls of childbearing potential with mild intellectual disability and mental capacity should be involved in the discussion regarding valproate and pregnancy risk wherever possible. This patient population are often very vulnerable and pharmacists must be alert to safeguarding issues (e.g. potential for sexual abuse)[18]

. Pharmacy staff should be encouraged to be aware of the support and pathways to appropriately raise any concerns. Most organisations will have a safeguarding policy and a designated safeguarding lead. Alternatively, pharmacists could consider contacting their superintendent pharmacist for advice.

Switching therapies

Switching from valproate to alternative antiepileptic drugs also presents many challenges. A recent retrospective review of female patients aged 15-30 years with idiopathic generalised epilepsy, who were switched from valproate to alternative antiepileptic drugs, demonstrated worsening seizure control in 70.6% of cases[29]

.

In addition, under Driver and Vehicle Licensing Authority regulations, women who are changing antiepileptic drugs will be advised to stop driving during drug substitution and for six months thereafter[30]

. This can have an impact on the patients’ ability to work as well as having potential psychosocial consequences[31]

.

Changes to practice during COVID-19

In May 2020, the MHRA published guidance on how to handle issues that may arise regarding the valproate PPP during the COVID-19 pandemic[32]

. This guidance states that the PPP must still be commenced in women or girls of childbearing potential, who have been newly initiated on valproate during the pandemic, and that annual specialist reviews of existing patients should not be delayed[32]

.

The patient guide may be issued by the specialist prescriber to the patient electronically during COVID-19[32]

. Consequently, community pharmacists may notice an increased demand from patients preferring physical copies when handing out prescriptions and should consider ordering extra from Sanofi medicines information (tel: 0800 035 2525; email: medicalinformation@sanofi.com [UK]). Changes to the contraceptive advice during COVID-19 has been published by the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare and is summarised in Box 3[32],[33],[34]

.

As the most accessible patient-facing healthcare professionals, pharmacists should educate patients on the effective use of any contraceptives commenced during the pandemic. As we adjust to ‘the new normal’, pharmacists will also need to identify patients who require restoration of highly effective contraception and refer them to the relevant services.

Box 3. Changes to the valproate pregnancy prevention programme contraception advice during the COVID-19 pandemic

- The provision of contraception for patients on valproate is considered a priority service. Where the provision of highly effective contraception is not possible for new patients owing to service provision during the pandemic, the Faculty of Sexual Health and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) advises:

- Progestogen-only pill (POP) plus a barrier method can be offered, provided there are no contraindications (e.g. concomitant enzyme-inducers);

- Pregnancy testing will be required, as per the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency COVID-19 advice, the result of which should be verified by the prescriber (e.g. via email or phone).

- The replacement of certain highly effective longer-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) can be deferred for a year, as limited evidence suggests that the risk of pregnancy is very low. Specifically, this applies to:

- Nexplanon (Merck Sharpe & Dohme Limited), the progestogen-only implant;

- Mirena (Bayer) and Levosert (Gedeon Richter [UK] Ltd), brands of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system.

- Other LARCs must be replaced within their licensed period to remain highly effective contraceptives. If this is not possible due to the pandemic, alternative contraception will be required at the end of their licensed lifecycle (e.g. POP plus barrier method). This applies to:

- Jaydes (Bayer) and Kyleena (Bayer) brands of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system;

- Copper intrauterine devices (see FSRH guidance for specific cases where effective for longer).

- The provision of LARCs has been prioritised under Recovery Phase 1 of the FRSH restoration of services following COVID-19[32],[33],[34]

.

Patient safety

The Cumberlege report, ‘First Do No Harm’, published in July 2020, looked at those who have suffered avoidable harm from healthcare, including the use of valproate in pregnancy[35]

. The report made wide-reaching recommendations, including that a similar system to the valproate PPP should be implemented for any medicine with known teratogenic potential[35]

.

The report also recommended that a prospective registry should be established that necessitates mandatory reporting of data relating to all pregnancies which occur in women on antiepileptic drugs and collation of data over the child’s/children’s lifetime[35]

. It is hoped that such a registry will result in the teratogenic potential of antiepileptic drugs being clearly elucidated so that prescribers and patients can make more informed choices.

The MHRA continues to monitor the impact of, and adherence to, the PPP, and is considering other measures to improve patient safety, including the development of a valproate registry[36]

.

Following publication of the Cumberlege report, there is renewed need for pharmacist and pharmacy teams to fully engage in educating women or girls of childbearing potential about the risks of valproate in pregnancy and adhering to the dispensing rules stipulated in the Guide for Healthcare Professionals

[6]

.

There are several key messages that pharmacists should bear in mind (see Box 4).

Box 4: Key safety messages

- Sodium valproate should not be used in female children and women of childbearing potential unless other treatments are ineffective or not tolerated;

- Sodium valproate is contraindicated in pregnancy for the treatment of epilepsy unless there is no suitable alternative treatment. For patients treated for bipolar disorder, sodium valproate is contraindicated in pregnancy;

- Sodium valproate is contraindicated in women of childbearing potential unless the conditions of PREVENT, the valproate pregnancy prevention programme, are fulfilled.

Peer-reviewed article

This article has been peer reviewed by relevant subject experts prior to acceptance for publication. The reviewers declared no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or in financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this article.

Financial and conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

Sponsored content

Sanofi provided financial support in the production of this content and has reviewed this content to ensure compliance with the ABPI code of practice. The Pharmaceutical Journal retains sole development and editorial responsibility of the contents.

MAT-GB-2003340 V1.0 DOP December 2020

About the authors

Vanessa Eustace is a specialist neurosciences pharmacist at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Shelley Jones is a consultant neurosciences pharmacist at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Gill Yates is a senior lecturer in pharmacy practice (neurology) at the School of Pharmacy, University of Sussex and a bank neurology pharmacist at Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust; and Grant O’Neil is a specialist neurosciences pharmacist at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London.

References

[1] Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. [Online version] 79th ed. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press; 2020. Available at: http://www.medicinescomplete.com (accessed September 2020)

[2] Care Quality Commission. High risk medicines: valproate. 2020. Available at: https://www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-providers/adult-social-care/high-risk-medicines-valproate (accessed September 2020)

[3] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Epilepsies: diagnosis and management. 2012. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg137/resources/epilepsies-diagnosis-and-management-35109515407813 (accessed September 2020)

[4] Summary of product characteristics. Epilim Chrono (sodium valproate) 500mg controlled release tablets (Sanofi). Available at: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1444/smpc (accessed September 2020)

[5] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Valproate use by women and girls. 2018. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/valproate-use-by-women-and-girls (accessed September 2020)

[6] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Guide for healthcare professionals: information on the risks of valproate (Epilim, Depakote, Convulex, Episenta, Epival, Kentlim, Orlept, Sodium Valproate, Syonell, Valpal & Belvo) use in girls (of any age) and women of childbearing potential. 2019. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/860761/Booklet-for-healthcare-professionals.pdf (accessed September 2020)

[7] Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. ABPI Data Sheet Compendium 1975. 2nd ed. London: Datapharm Publications; 1975.

[8] European Medicines Agency. Valproate and related substances. 2014. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/valproate-related-substances (accessed September 2020)

[9] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Medicines related to valproate: risk of abnormal pregnancy outcomes. 2015. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/medicines-related-to-valproate-risk-of-abnormal-pregnancy-outcomes (accessed September 2020)

[10] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Valproate and risk of abnormal pregnancy outcomes: new communication materials. 2016. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/valproate-and-of-risk-of-abnormal-pregnancy-outcomes-new-communication-materials (accessed September 2020)

[11] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. CPRD study monitoring the use of valproate in girls and women in the UK. 2018. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5c17a778e5274a46612cda3c/CPRD-valproate-usage-17122018.pdf (accessed September 2020)

[12] Epilepsy Action. Almost one-fifth of women taking sodium valproate for epilepsy still not aware of the risks in pregnancy, survey shows. 2017. Available at: https://www.epilepsy.org.uk/news/news/almost-one-fifth-women-taking-sodium-valproate-epilepsy-still-not-aware-risks-pregnancy (accessed September 2020)

[13] European Medicines Agency. PRAC recommends new measure to avoid exposure in pregnancy. 2018. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/prac-recommends-new-measures-avoid-valproate-exposure-pregnancy (accessed September 2020)

[14] European Medicines Agency. New measure to avoid exposure in pregnancy endorsed. 2018. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/new-measures-avoid-valproate-exposure-pregnancy-endorsed (accessed September 2020)

[15] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Valproate medicines (Epilimâ–¼, Depakoteâ–¼): contraindicated in women and girls of childbearing potential unless conditions of Pregnancy Prevention Programme are met. 2018. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/valproate-medicines-epilim-depakote-contraindicated-in-women-and-girls-of-childbearing-potential-unless-conditions-of-pregnancy-prevention-programme-are-met (accessed September 2020)

[16] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Valproate medicines and serious harms in pregnancy: new Annual Risk Acknowledgement Form and clinical guidance from professional bodies to support compliance with the Pregnancy Prevention Programme. 2019. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/valproate-medicines-and-serious-harms-in-pregnancy-new-annual-risk-acknowledgement-form-and-clinical-guidance-from-professional-bodies-to-support-compliance-with-the-pregnancy-prevention-programme (accessed September 2020)

[17] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Medicines with teratogenic potential: what is effective contraception and how often is pregnancy testing needed. 2019. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/medicines-with-teratogenic-potential-what-is-effective-contraception-and-how-often-is-pregnancy-testing-needed (accessed November 2020)

[18] Shakespeare J & Sisodiya SM. Guidance document on valproate use in women and girls of childbearing years (Version 1). Royal College of General Practitioners, Association of British Neurologists and Royal College of Physicians. 2019. Available at: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/CIRC/Epilepsy/RCGP-pan-college-valproate-march-2019.ashx?la=en (accessed September 2020)

[19] Pfäfflin M, Schmitz B & May TW. Efficacy of the epilepsy nurse: results of a randomized controlled study. Epilepsia 2016;57(7):1190–1198. doi: 10.1111/epi.13424

[20] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Safe supply of valproate medication. 2017. Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/quick-reference-guides/dispensing-valproate-for-girls-and-women (accessed September 2020)

[21] Whincup PH, Gilg JA, Odoki K et al. Age of menarche in contemporary British teenagers: survey of girls born between 1982 and 1986. BMJ 2001;322:1095. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1095

[22] Harden C, Tomson T, Gloss Det al. Practice guideline summary: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy incidence rates and risk factors: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr 2017;17(3):180–187. doi: 10.5698/1535-7511.17.3.180

[23] Hovinga CA, Asato MR, Manjunath R et al. Association of non-adherence to anti-epileptic drugs and seizures, quality of life, and productivity: survey of patients with epilepsy and physicians. Epilepsy & Behavior 2008;13(2):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.03.009

[24] Sveberg L, Svalheim S & Tauboll E. The impact of seizures on pregnancy and delivery. Seizure 2015;28:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.02.020

[25] General Pharmaceutical Council. GPhC statement on supplying valproate safely to women and girls. 2018. Available at: https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/news/gphc-statement-supplying-valproate-safely-women-and-girls (accessed September 2020)

[26] Company Chemists’ Association. Valproate medicines safety in community pharmacy: practice-based audit 2018-19 summary report. 2019. Available at: https://thecca.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Valproate-safety-audit-report.pdf (accessed September 2020)

[27] Epilepsy Action, Young Epilepsy, Epilepsy Society. Valproate Survey 2020. Epilepsy Society; London. Available at: https://www.epilepsysociety.org.uk/news/women-still-unaware-risks-around-epilepsy-medicines-pregnancy-aug2020 (accessed September 2020)

[28] NHS England and NHS Improvement. Pharmacy Quality Scheme Guidance 2019/2020. 2019. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/pharmacy-quality-scheme-guidance-2019-20/ (accessed September 2020)

[29] Irelli EC, Morano A, Cocchi E et al. Doing without valproate in women of childbearing potential with idiopathic generalised epilepsy: implications on seizure outcome. Epilepsia 2020;61(1):107–114. doi: 10.1111/epi.16407

[30] Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency. Assessing fitness to drive – a guide for medical professionals. 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/assessing-fitness-to-drive-a-guide-for-medical-professionals (accessed September 2020)

[31] Sen A & Nashef L. New regulations to cut valproate-exposed pregnancies. Lancet 2018;392(10146):458–460. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31672-6

[32] Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Valproate Pregnancy Prevention Programme: temporary advice for the management during coronavirus. 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/valproate-pregnancy-prevention-programme-temporary-advice-for-management-during-coronavirus-covid-19 (accessed September 2020)

[33] The Faculty of Sexual Health and Reproductive Healthcare of the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists FRSH CEU clinical advice to support provision of effective contraception during the COVID-19 outbreak. 2020. Available at: https://www.fsrh.org/documents/fsrh-ceu-clinical-advice-to-support-provision-of-effective/ (accessed September 2020)

[34] The Faculty of Sexual Health and Reproductive Healthcare of the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. FRSH restoration of SRH services during COVID-19 at a glance. 2020. Available at: https://www.fsrh.org/documents/fsrh-phased-approach-restoration-srh-services-covid-19/ (accessed September 2020)

[35] The Independent Medicines & Medical Devices Safety Review. First do no harm: the report of the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review. 2020. Available at: https://www.immdsreview.org.uk/Report.html (accessed September 2020)

[36] Department of Health & Social Care. Secretary of State Matt Hancock to chair of Health and Social Care Committee RE: The Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review. 2020. Available at: https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/3372/documents/32328/default/ (accessed November 2020)