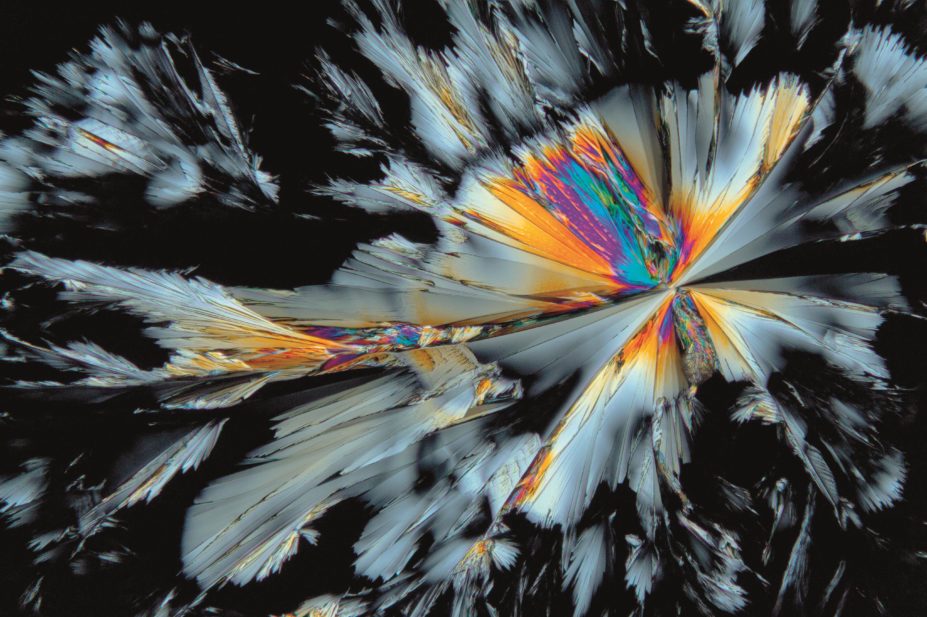

Antonio Romero / Science Photo Library

Primary care physicians are increasingly prescribing antidepressants for conditions other than depression, including off-label indications, data from Canada show.

Researchers, led by Jenna Wong from McGill University in Montreal, Canada, found that over the past ten years, only around half of all antidepressant prescriptions were for depression.

“While this prescribing phenomenon has been suspected among the medical community for quite some time, no studies to date have confirmed this hypothesis because documented treatment indications are unavailable in virtually all settings,” says Wong.

The research, published in JAMA

[1]

(online, 24 May 2016), used data from a community-based electronic medical record platform involving around 100,000 patients and 185 physicians in Quebec. Physicians taking part in the study had to provide at least one indication per prescription.

The team found that, from January 2006 to September 2015, there were 101,759 antidepressant prescriptions, excluding monoamine oxidase inhibitors, given to 19,734 patients, but only 55.2% of these were indicated for depression.

Two out of three non-depressive indications were unapproved, the most common being insomnia (10.2% of all prescriptions) and pain (6.1%). Antidepressants were also prescribed off-label for migraine, vasomotor symptoms of menopause, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and digestive system disorders.

Anxiety disorders (18.5%) and panic disorders (4.1%) were also common among non-depressive indications.

The researchers found that, over the course of the study, the percentage of antidepressants prescribed for depression fell significantly for serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants.

Wong says that although the researchers didn’t explore why doctors were increasingly prescribing antidepressants for non-depressive indications, the trend could be related to concerns about safety of existing treatments.

“Possible reasons include promotion and marketing by pharmaceutical industries and the perception that newer antidepressants are safer than other therapies commonly used to treat conditions such as anxiety and insomnia (e.g. benzodiazepines and anxiolytics),” Wong says.

She adds that doctors may not always be aware they are prescribing antidepressants off-label, or may presume a drug class effect.

The authors conclude that more needs to be done to evaluate the efficacy of antidepressants for off-label use.

“In our opinion, off-label prescribing of antidepressants is a concern, particularly when there is a lack of scientific evidence to support the drug’s safety and effectiveness for the indication,” says Wong. “The negative consequences of off-label prescribing include exposing patients to unknown health risks and creating unnecessary healthcare costs,” she adds.

Liz England, mental health lead at the Royal College of General Practitioners, the academic organisation in the UK for GPs, says she imagines off-label prescribing levels in Canada are probably similar to the UK, and while there are risks with off-label prescribing, GPs are not likely to be prescribing these treatments carelessly.

She adds that doctors are likely to follow national or local prescribing guidelines for a patient initially, but may consider prescribing a treatment off-label when these fail. She says that GPs might prescribe antidepressants for conditions that are not easily treated with drugs, such as insomnia. In some areas, there may not be good access to psychological therapies like cognitive behavioural therapy, and doctors can be averse to prescribing sleeping tablets, she adds.

“Patients don’t always present with one problem either,” England says. “It’s quite common for somebody to present with chronic pain, insomnia, low mood, they might have diabetes and neuropathic symptoms. In which case you’d try to look for one medication that covers all of those but it may not be licensed for all of those.”

England says that the important thing is for GPs to have transparency and clarity with their patient.

“I’m quite honest with my patients; if you’ve got insomnia, 99% of the time it’s psychological, and the only way you’ll really treat it is to get to the bottom of the psychological cause,” she says. “But in the meantime, there may be something that helps improve your quality of life or just means you get out of bed on a daily basis.”

References

[1] Wong J, Motulsky A, Eguale T et al. Treatment indications for antidepressants prescribed in primary care in Quebec, Canada, 2006–2015. JAMA 2016;315:2230–2232. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3445