Corrinne Burns / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Saturday 8 April 2017 ushered in the first truly warm day of the year, and the second annual conference of the Humanitarian Aid and Response Network (HARN). Hosted on the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s (RPS) website, the HARN — established by humanitarian aid pharmacist Trudi Hilton — brings together RPS members interested in working in disaster zones and other resource-poor settings.

The one-day conference was held at Brighton and Sussex Medical School at the University of Sussex. Organised by Hilton and Sarah Marshall, a teaching fellow at the school, the event focused on the challenges for pharmacy in resource-poor settings. Catherine Duggan, director of professional development and support at the RPS, opened the day with heartfelt words on the UK’s “duty and privilege” to share “our guidance, our support and our toolkits”.

Duggan also spoke of her belief that UK pharmacists form a “skilled and competent workforce ready to pick up the gauntlet” of international assistance — particularly in a time when the concept of care is “all too often absent” from political discourse.

Waste of resources

The need for “skilled and competent” pharmacists in resource-poor areas was expanded upon by Kathleen Holloway in her inaugural lecture, “Promoting rational use of medicines”. Holloway considered the reasons behind irrational prescribing — a term that, broadly, refers to the habitual prescription of medicine that is ineffectual, unsuitable, or altogether unnecessary. Holloway is a medical doctor with interest in the appropriate use of medicines, including antibiotics, in low and middle-income countries. From 1999 until her retirement in 2016, Holloway worked for the World Health Organizaion (WHO), latterly in the WHO’s South East Asia regional office (SEARO), as regional advisor in essential drugs and other medicines.

Source: Corrinne Burns / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Kathleen Holloway, medical doctor and former regional advisor in medicines in South East Asia at the World Health Organization, has a particular interest in promoting the appropriate use of antibiotics and medicines.

In one multi-country study, Holloway observed that more than 60% of patients with upper respiratory tract infections were inappropriately given antibiotics. This is “more than a waste of precious resources,” she said, adding that it can also lead to lack of lack of drug effect, adverse reactions, and antimicrobial resistance.

Holloway advocates a non-confrontational, no-blame approach to addressing irrational use. “It’s not that people themselves are irrational,” she told delegates, adding that people “often have rational reasons for using drugs irrationally”, lack of time and peer pressure, for example. Overworked, time-poor healthcare staff may prescribe multiple medicines to be on the “safe” side; in busy pharmacies lack of patient-dispenser interaction time — which can be as little as a few seconds — means staff don’t always have enough time to fully explain how to take their medicine. Some hospitals — Holloway preferred not to say where — are so busy that they don’t record oral drugs given to patients.

Billions of pounds are spent on medicines development and promotion, and comparatively little is spent on encouraging the rational use of those medicines, Holloway said. To address this “serious global health problem”, she said that nationwide changes in policy are needed, including prescription audits and the enforcement of prescription-only access to new antibiotics (rather than allowing them to be sold over the counter). Policy change must be coupled with education and supervision of healthcare providers and consumers; the latter includes workshops with national stakeholders, and community case management.

An expired medicine is not better than nothing. Unless the donation comes from an appropriate organisation, we can’t accept it

There is a very big role for the pharmacist in the promotion of rational use of medicines, Holloway added. She highlighted pharmacists’ expertise in prescription monitoring, medicines consumption and supply management, as well as the potential for pharmacists in policy change, saying that she would “like to see pharmacists at national level, managing and regulating the use of medicines”.

Showcasing pharmacy

Up next was Trudi Hilton who, after a 20-year career in NHS pharmacy, now acts as an ambassador for what pharmacists bring to humanitarian aid. In her presentation, Hilton spoke of her experiences (both personal and professional) of managing the pharmaceutical supply chain in disaster zones. Being female is an active advantage in the humanitarian field, Hilton told delegates. Women are generally allowed to speak to anyone, she explained, and are less likely to be suspected of espionage than men. However, she reminded delegates that “there is no ‘white flag’ anymore. “You have to accept that you may not come back.” Kidnappings and even murders of humanitarians are a reality, Hilton added.

When importing medicines, it is often the “final mile” in a drug’s journey that is the most trying (and expensive), Hilton explained, not least because this is often the point at which the cold chain breaks down. She said how she had once witnessed the accidental wastage of an oxytocin shipment. “It was fine when it got off the plane. Then it spent two hours in the back of a truck, at 40°C.” Ensuring the quality of medication is a big part of humanitarian pharmacy, she said – especially when responding to well-intended requests to donate expired medicines. “An expired medicine is not better than nothing. Unless the donation comes from an appropriate organisation, we can’t accept it.”

Hilton also expressed a hope for better collaboration between donors: transport logistics can be complicated by some donors’ refusals to share delivery containers, because the donor’s name is on the box — a practice that “has got to stop.”

The difficulties of getting medicines to refugee settlements has been documented previously in The Pharmaceutical Journal

. Importing drugs from the international market can be costly. Ethiopia has a total restriction on importing any medicines at all, so locally produced pharmaceuticals must be used. In many countries, Hilton explained, the government will allow aid agencies to import medicines, but these must then be quality assessed, adding waiting times of up to six weeks. Substandard medicines still cast a long shadow: counterfeit medications can be more profitable to traffickers than narcotics, with the added bonus that shipping counterfeits is likely to bring a lesser sentence, compared to narcotics, to those who are caught.

While humanitarian work is not a soft option, Hilton’s deeply-held belief in her work was palpable: there is great potential for pharmacists to make lasting change, not least in advocating for humanitarian pharmacy. She had recently returned from Yemen, where she was “demonstrating the value pharmacists can add”.

Don’t rush into a humanitarian career straight from university — get experience in the NHS first

But, she added: “Everywhere I’ve left, a pharmacist has come in after me.” To those wishing to follow Hilton into a humanitarian career, she offers this advice: “Don’t rush into it straight from university. I would strongly encourage you to get experience in the NHS first.”

Sustainability is crucial

Barbara Pawulska, the next speaker, brought 30 years of experience across the UK’s community, hospital and industrial pharmaceutical sectors to her present career with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). Pawulska told delegates that MSF actively recruits pharmacists both in its headquarters and in the field. The organisation employs three pharmacists in Amsterdam, who track down and purchase quality-assured medication for field use. Pawulska highlighted that this is a hugely responsible position, as MSF is legally responsible for the quality of the medicines it provides, and also for ensuring good storage and distribution practices.

Source: Corrinne Burns / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Barbara Pawulska, a pharmacist currently working with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), has been deployed to the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Pawulska also emphasised the responsibility of humanitarian pharmacists to train and supervise national staff: “Sustainability is crucial. As international staff on a mission, you are there for a short time, so you want to avoid starting interventions that can’t continue when you’re gone”, she said. MSF established 24 community health centres in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo: ten in the town of Baraka and 14 in the Kimbi Lulenghe region. In each centre local staff were trained to manage the site, with regular overview from a pharmacist to keep an eye on stock management.

Do we provide no pharmaceuticals at all, or take the risk of prescribing substandard medicines?

Forecasting — making informed decisions on the type and amount of medications needed for a mission — is another crucial skill that pharmacists bring, said Pawulska. Forecasting must be accompanied by consumption monitoring: if more prescriptions are issued than forecasted, it is the pharmacist’s job to find out why. Prescribing audits might then be needed. Auditing is not just a matter of keeping costs down, said Pawulska: over-ordering of medicines can exacerbate inappropriate prescribing.

Mitigating risk

Also speaking about experiences in Africa was Owen Wood, previously a ‘flying pharmacist’ with MSF and now a humanitarian pharmacy adviser with Save the Children (STC), is one of six pharmacists at STC’s London office. Wood spoke about his recent experience in southern Uganda where he was based in the Bidi Bidi refugee settlement, now believed to be the largest in the world.

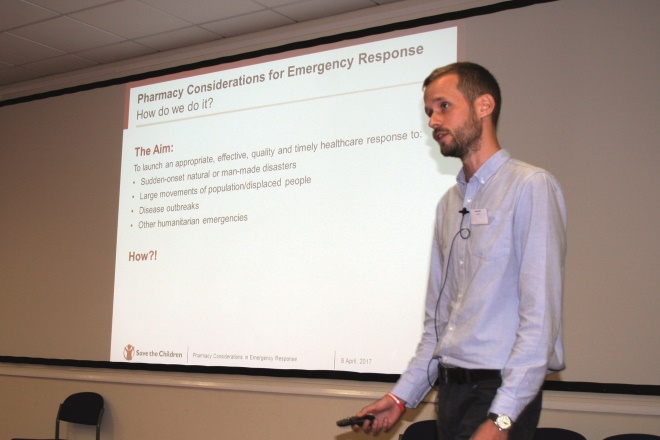

Source: Corrinne Burns / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Owen Wood, humanitarian pharmacy adviser with Save the Children, shared his experiences of working in Uganda.

Uganda does not allow medicines to be brought into the country from overseas. The country has a growing manufacturing market which the government wants to protect from imported drugs. This, he says, presents a challenge to humanitarian pharmacists: “Do we provide no pharmaceuticals at all, or take the risk of prescribing substandard medicines?” Wood’s experience was that while Kampala, the capital city, has some good medicines suppliers and storage facilities, it isn’t possible to guarantee the quality of all locally-obtained pharmaceuticals. In Bidi Bidi, STC decided that sourcing drugs locally is better than not responding at all. But risks must be mitigated, not least by “engaging with suppliers and regulators. It’s part of our job to help build capacity for regulatory assurance.” Wood led a pharmacovigilance project in the camp. “It’s one way to identify poor quality. If we see adverse reactions across sites, we take action.” Follow-up phone calls to a patient’s mobile are a simple but effective means of active surveillance for adverse reactions, he said, as is working with local community health workers.

The view from Nigeria

A slightly different angle of humanitarian pharmacy was discussed by Eneyi Kpokiri, a pharmacist and PhD student at University College London. Kpokiri is conducting research into antimicrobial prescribing in her home country of Nigeria. She began by briefing delegates on the country’s current healthcare situation (including the great disparity in quality of healthcare in private and public healthcare settings). Nigeria has the largest infectious disease burden in the world and yet, said Kpokiri, irrational prescribing of antimalarials, antihypertensives and antibiotics persists in Nigerian hospitals.

Source: Corrinne Burns / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Eneyi Kpokiri, a pharmacist and PhD student at University College London. Kpokiri is researching antibiotic prescribing in her home country of Nigeria.

As part of her PhD, Kpokiri studied antibiotic prescribing in hospitals across Nigeria’s Bayelsa state between January 2015 and December 2015. Almost a third (31.1%) of antibiotics prescribed were given for respiratory tract infections, which are usually viral in nature. Kpokiri also observed widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Kpokiri is now studying the reasons behind these prescribing behaviours, and recommends that all hospitals in Nigeria should adopt an antibiotic use policy stating that there should be regular audits for antibiotic prescribing patterns; more training of prescribers is needed; and restrictive antibiotic dispensing practise including checks by a pharmacist.

Commonwealth opportunities

The diversity of humanitarian aid exemplified by the day’s speakers led neatly into Raymond Anderson’ s presentation. Anderson, president of the Commonwealth Pharmacist’s Association (CPA), gave a brief outline of the CPA’s remit. The CPA is a non-governmental organisation representing pharmaceutical societies and individual pharmacists from the Commonwealth countries, and Anderson encouraged those interested in humanitarian pharmacy to get involved.

A large part of the CPA’s remit is to connect pharmacists around the Commonwealth to share support and expertise, especially with those pharmacists working in resource-poor settings. Anderson invited delegates to register their interest and skills on the CPA’s website, pointing out that around one third of the world’s population lives in the Commonwealth – many in low and middle-income countries – so membership of this association offers a good way to develop a career in the humanitarian field.

The future workforce

Finally, Sarah Marshall, teaching fellow in global health at the Brighton and Sussex Medical School introduced a brand new postgraduate course for pharmacists wishing to make a career in humanitarian pharmacy, or other aspects of global pharmacy. To date, there has been no formal career structure for pharmacists interested in aid work, but September 2017 will see the first cohort of entrants to the Global Pharmacy masters, postgraduate diploma and postgraduate certificate.

Of the 58 delegates in attendance at the conference, around half were pharmacy students wanting to find out more about a humanitarian career. They’ll certainly be needed. While the value of field pharmacists has yet to be fully recognised, almost all speakers on the day spoke of how their work had changed perceptions. Advocating for pharmacy in humanitarian work is an ongoing, but vital, process.