Chris Ison/PA Archive/PA Images

Source: Dominic Lipinski / PA Wire / PA Images

Gosport Independent Panel’s report questions the pharmacists and the NHS trust’s drugs and therapeutics committee for failing to challenge prescribing practices between 1989 and 2000

The inquiry report into the scandal at Gosport War Memorial Hospital in Hampshire, where at least 450 patients died between 1989 and 2000, makes chilling reading.

The Gosport Independent Panel, which published its report in June 2018, describes the hospital as a place where there was a “disregard for human life and a culture of shortening the lives of a large number of patients by prescribing and administering ‘dangerous doses’ of a hazardous combination of medication not clinically indicated or justified”.

The 387-page report says there is no evidence that pharmacists and the Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust drugs and therapeutics committee challenged the prescribing practices over the years.

It specifically questioned how anticipatory prescribing — typically where patients who are terminally ill are prescribed medicines “just in case”, ahead of obvious clinical need — was adopted at Gosport.

While the report acknowledged that the practice of anticipatory prescribing was still in its early days in the 1990s, the panel expressed concern about the range of doses nurses were given the power to administer, and that anticipatory prescribing was used in cases where patients had been admitted for respite or rehabilitation — not terminal care.

At the same time, the panel found that opioids were used without appropriate clinical need; that patients were stared on “inappropriately high doses of opioids”; and that the opioids were combined with other drugs in “high” doses.

So what can pharmacy learn from the Gosport report? Was Gosport unique? And is the profession confident that the practices and culture which existed then, has changed enough, to prevent another tragedy happening again?

Graeme Richardson, president of the Guild of Hospital Pharmacists (GHP) and chief pharmacist at South Tyneside NHS Foundation Trust, comments: “I don’t think [Gosport] could happen again. Never say never, but I do think the culture has changed and we are in much better place than we were.”

Source: Courtesy of Graeme Richardson

Graeme Richardson, president of the Guild of Hospital Pharmacists and chief pharmacist at South Tyneside NHS Foundation Trust, is confident that Gosport is unlikely to happen again

His optimism is shared by others across the sector who believe that pharmacists today are listened to by their colleagues and are more likely to raise concerns. A focus on governance — from inside the trust as well as from outside inspectors and regulators — is another reason why many believe Gosport is less likely today.

If nobody knew about the issues going on in pharmacy then how could they fix it?

Having read the whole inquiry report, Alison Ewing, clinical director of pharmacy at the Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust and professor of pharmacy innovation at Liverpool John Moores University, says she remains unconvinced that prescribing was audited and monitored at Gosport at the time, so prescribing trends would not have been picked up.

“My first gut instinct on reading the report was ‘where is pharmacy in all of this?’ I wasn’t aware of its presence, which is very sad given what was going wrong. If nobody knew about the issues going on in pharmacy then how could they fix it? I don’t know if in this case the pharmacist felt empowered,” she says.

During the years scrutinised by the panel — from 1989 to 2000 — the hospital would not have had access to electronic patient records, meaning that pharmacists and others would have had to rely on paper case notes, which may have stifled pharmacist involvement, Ewing says. “Chances are the case notes would have been locked away somewhere and maybe there was a culture that the pharmacist didn’t get involved in the case notes,” she suggests.

The Guild of Hospital Pharmacists would actively support members should they be seeking to raise concerns, especially around patient safety

Today, however, advances in technology and the use of electronic patient records means that clinicians are more accountable than ever before. “For example, in my trust everybody is accountable for what they see and can’t see. Everything is tagged with your initials. So if there is an error and the pharmacist hasn’t looked at the case notes I would know,” she explains.

Source: Chris Ison / PA Archive / PA Images

Gosport War Memorial Hospital, where at least 450 patients died between 1989 and 2000

Lessons learned

Patient safety has also jumped to the top of the agenda since Gosport, according to Richardson: “Not only do pharmacists work more closely with medical colleagues, the more general progress around patient safety — including learning from other industries, such as aviation — has promoted a culture where speaking up is positively encouraged. There is a long way to go with this, but the progress since Gosport has been significant.

“As a union, the GHP would actively support members should they be seeking to whistle-blow or raise concerns especially around patient safety,” he adds.

Every trust must have its own medical safety officer today — that didn’t happen before

This stand is shared by Ewing, who says: “My staff all know that I put patient safety before anything. If they have any concerns, if they have a real problem about ‘Dr X’, there is a proper network of line managers. There is a system in place so that if any nurse on any ward has any concerns they would contact the ward pharmacist.”

Ewing adds that clinical governance is well established, senior pharmacists are involved at every stage and there is a culture of incident reporting with events being recorded online. “Incident reports are looked at weekly by the trust’s medical safety officer, so we would see trends,” she explains. “Every trust must have its own medical safety officer today — that didn’t happen before.”

The status of pharmacy and the enhanced professional reputation of pharmacists, which means they are expected to be part of a multidisciplinary team, was very different in the 1980s and 1990s. Ewing says: “I’ve been here for 17 years and the feeling has gone from pharmacists being seen as being a nuisance to pharmacists being seen as being an essential part of good quality patient care.”

Independent prescribing has also boosted pharmacists’ reputation with other clinicians in recent years, Richardson adds. “Pharmacists now work far more closely with their medical colleagues to influence prescribing and discuss or challenge prescribing where required, and are actively involved in multidisciplinary team patient care discussions.”

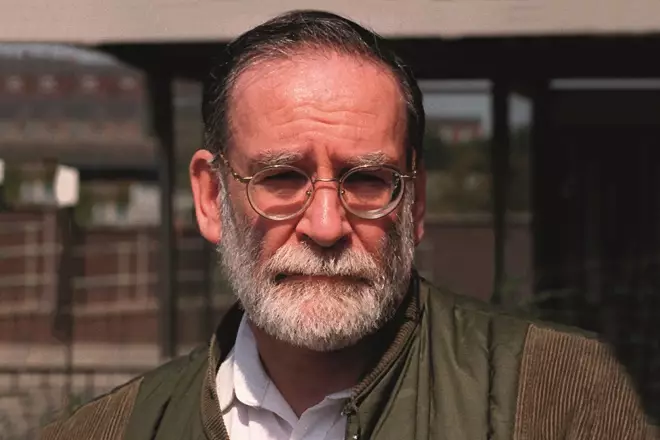

Source: EC / allactiondigital.com / Eamonn and James Clarke / PA Images

Lessons learned from the Harold Shipman inquiry came too late to influence what was happening at Gosport

The case of Harold Shipman — the Hyde GP who was found guilty of murdering 15 of his patients with lethal doses of diamorphine — and the subsequent inquiry which found that Shipman may have caused 250 over a period of 23 years, has also been influential in increasing monitoring of controlled drugs and accountability across the NHS. But these lessons learned from the 2001 Shipman inquiry came too late to influence what was happening at Gosport.

Prescribing practice

Today, there is a national controlled drugs local intelligence network responsible for scrutinising controlled drugs, run by NHS England, and set out in regulations introduced in 2013. Clinical audits are established in trusts and are an additional layer of scrutiny for prescribing practice and patterns. Ewing explains: “I am the controlled drugs accountable officer for Liverpool and that means that I am informed of any incidents, [which then enables me to] decide, for example, if somebody has just dropped a bottle of morphine or if it means that there are 100 tablets missing.”

The Care Quality Commissioner (CQC) itself, the independent regulator set up to inspect and rate hospital and social care services, is also quite a newcomer to the NHS landscape as it was only established in 2009. “We welcomed the newer CQC inspection process, which has more of a focus on prescribing practice, including anticipatory medicines, but we feel that this could be improved further,” he says.

Richardson is concerned that the misuse of anticipatory prescribing at Gosport might trigger loss of public confidence in the practice and threaten its continued use. He says: “We would hope that this incident does not mean that the use of anticipatory prescribing is seen itself as a bad thing by the public.

Anticipatory prescribing is not wholly associated with end-of-life situations

“[This] term can cover entirely appropriate post-operative pain relief or rapid tranquilisation and is not wholly associated with end-of-life situations. Pharmacists are well placed to advise on and monitor the use of anticipatory prescribing and this supports the case for clinical pharmacists and pharmacist prescribers to be an integral part of every clinical team.”

Nina Barnett, a consultant pharmacist at London North West Healthcare NHS Trust, has previous pharmacy expertise in the care of older people. She says the Gosport report is not the first to challenge poor prescribing. “It probably won’t be the last, but we are on rapid trajectory to reduce to zero these kind of issues.”

Source: Courtesy of Nina Barnett

Consultant pharmacist Nina Barnett says a lack of guidelines is partially to blame for the pharmacy failings at Gosport

Barnett says it is crucial to recognise that the panel found Gosport guilty of inappropriate use of anticipatory prescribing. “Appropriate anticipatory prescribing hasn’t given us any problems. But Gosport was about inappropriate anticipatory prescribing. I think what went wrong here was not knowing what the people were in hospital for. Did the doctor think the patient was dying? Did the pharmacist think the patient was dying? How much access might they have had to information about the diagnosis of the patient at that time? When it’s done well, there is nothing to beat anticipatory prescribing, it gives people what they need in terms of medicines optimisation.”

While one wouldn’t wish to defend inappropriate or unsafe practice, given the circumstances, I can understand why it happened

She believes a combination of factors during the 1980s and 1990s contributed to what happened in pharmacy in Gosport: clinical pharmacy practice had not yet been developed, guidelines governing what good clinical practice looks like were not developed until the 1990s, and it was only when the internet took off in the 2000s that access to those guidelines was more commonplace.

And she says a combination of historic reasons and Gosport’s isolation came together to produce the circumstances that allowed problems to develop.

“I think everything conspired to make a Gosport more likely in Gosport in the 1980s and 1990s than a Gosport happening in a big London teaching hospital,” she says.

“While one wouldn’t wish to defend inappropriate or unsafe practice, given the circumstances, I can understand why it happened.”

The General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) will consider its response to the Gosport report at its council meeting on 12 July 2018. The pharmacy regulator confirmed when the panel report was published that the only pharmacist named in it — Jean Dalton — had voluntarily removed herself from the professional register in 2012 and that it had no jurisdiction to investigate pharmacists who were no longer on the professional register.

Dalton was employed by Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust, which had a service-level agreement to provide pharmacy services to the hospital in Gosport from 1994. Before that date, the pharmacy was part of Gosport’s outpatient department. The contract was managed by the Portsmouth trust’s chief pharmacist, who had overall responsibility for the service. The delivery of the service — including regular ward visits to review the drug charts and to check the drug stock — was down to Dalton, according to evidence given to the inquiry panel by a ward sister.

According to its July council papers, the GPhC intends to draw up a Gosport action plan which will include looking at the pharmacy services at the hospital, and the roles and responsibilities of the pharmacists at the time. Issues around pharmacists challenging poor prescribing and the monitoring of prescribing data will also be considered. The action plan is also set to focus on fitness-to-practise issues and what the GPhC can learn from the action taken by the doctor’s regulator the General Medical Council and the nurse regulator, the Nursing and Midwifery Council, in the Gosport case.

Source: Courtesy of David Reissner

Pharmacy law expert David Reissner says the GPhC needs to work out what could have been done differently at Gosport

David Reissner, an expert in pharmacy law and a consultant at Charles Russell Speechlys LLP says: “What I think the GPhC will have to consider is to look at what happened in Gosport and what could have been done differently that would have saved lives.

“But as I always say the whole of the healthcare system is based on trust. Pharmacists don’t automatically assume that a doctor is deliberately harming a patient — if they started with that assumption the NHS would grind to a halt.

“There has to be trust; so the real question in this case is, was there something that should have alerted the pharmacist to something being inappropriate and that is difficult if they didn’t have all the information [at that time]”