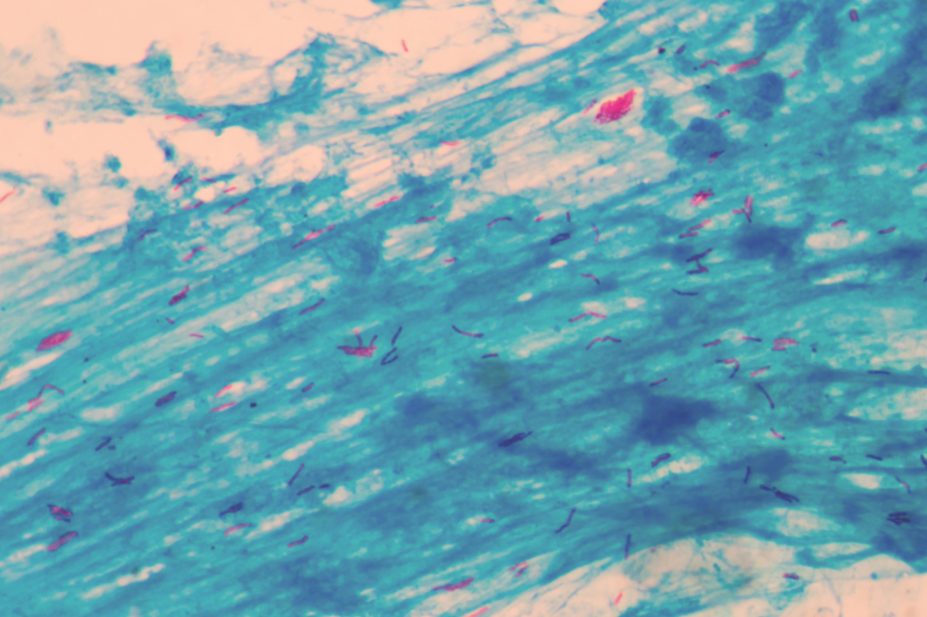

Shutterstock

Just 2% of people with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) have access to drugs that have been on the market for the past two years and which have the potential to save their lives, according to a report by charity Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

Price is a key barrier for patients accessing new drugs delamanid, marketed by Otsuka, and bedaquiline, marketed by Janssen, according to the MSF’s ‘Drug Resistant TB Drugs Under the Microscope’ report, published on 21 March 2016.

“It’s frustrating that after half a century, we finally have new TB medicines that can save the lives of the sickest patients, but we can’t offer this hope to all people who could immediately benefit,” says Yoseph Tassew, MSF’s medical coordinator for Russia.

“MSF is the only treatment provider able to offer delamanid to people in Russia, with seven patients on treatment so far. The potential of these new drugs means that I am seeing people with extensively drug-resistant TB walk out of the hospital who otherwise would be dead.”

Tassew says it is vital that companies and countries work to ensure that the large numbers of patients who could benefit from these drugs have access to them.

The World Health Organization’s Global Drug Facility (GDF) price for delamanid has been set at US$1,700 for a single treatment course for countries eligible under the Global Fund. But the price, says MSF, is “prohibitively expensive” for countries with a high burden of the disease.

MSF argues that the price of delamanid — which only has marketing approval in Europe, Japan and South Korea — could “feasibly” be slashed by 98% to make it affordable and accessible to the countries that need it most.

Janssen promises to provide 30,000 free courses of delamanid treatment to countries eligible for GDF funding, excluding South Africa, from April 2016. It also plans to introduce a three-tier bedaquiline pricing policy that will take into account an individual country’s ability to pay and its disease burden.

Under the scheme, a country classified as “high income” would pay US$30,000 for a six-month course of treatment, an “upper middle income” country would pay US$3,000 and the poorest countries would pay US$900.

MSF points out that price is not the only barrier to patients accessing treatments for drug-resistant TB. Access can be hindered because the drugs are not licensed for use in a particular country; are not included on a country’s national essential medicines list; or because there is a lack of country-level guidance to support their use.

Bedaquiline has so far been approved for use in 9 of 27 countries that have been recognised as having a high multidrug-resistant TB population. They include: Russia, India, South Africa, Philippines, Peru, South Korea, Turkmenistan and Armenia. There are nine submissions pending in other countries.

The MSF report recommends that the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, which raises and invests money to support programmes designed to eradicate these diseases, should introduce clear strategies for countries to ensure they can purchase TB drugs, even after they graduate from the fund’s support.

At the same time, the WHO’s GDF should look at how it can bid in national public tenders for countries that buy drugs outside of the GDF. The report says it is vital that those countries continue to procure and use quality-assured drugs.

“By publishing pricing data, we hope to contribute to countries’ ability to negotiate the lowest procurement price possible for quality assured drug resistant TB drugs. Countries that are able to obtain affordable, sustainable access to needed drug-resistant TB drugs have a better chance of reducing the growing number of drug-resistant TB cases.”